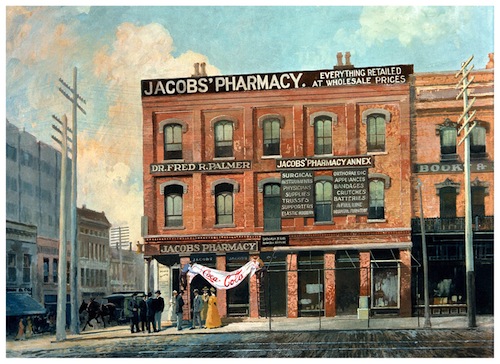

On May 8, 1886, pharmacist John Stith Pemberton hauled a jug of his latest patent medicine—a tonic he called Coca-Cola—over to Jacob’s Pharmacy on Peachtree Street. The syrup was mixed with soda water, deemed tasty, and sold for a nickel a glass. Coca-Cola was billed as a versatile drug that could “cure all nervous afflictions—Sick Headache, Neuralgia, Hysteria, Melancholy, Etc. …”

During the first year the beverage was on the market, Pemberton sold about nine glasses a day. The product name was coined by Pemberton’s bookkeeper, Frank Robinson, whose elegant penmanship is responsible for the company’s flourish-filled logo, which began to appear in Atlanta newspaper ads as well as on pharmacy awnings.

When Pemberton (shown right) died in August 1888, Coca-Cola was not even mentioned in the Atlanta Constitution’s story about his passing. What was mentioned, however, was the relationship between Coca-Cola’s inventor and fellow pharmacist Asa Griggs Candler, who summoned Atlanta’s druggists to his own shop to craft a tribute to Pemberton. “Our profession has lost a good and active member,” Candler told the newspaper. The pharmacists published a resolution honoring Pemberton, and they decided to attend his funeral services en masse, shuttering all Atlanta drug stores for the day in tribute to one of their own. Candler served as one of the “gentleman pallbearers.”

When Pemberton (shown right) died in August 1888, Coca-Cola was not even mentioned in the Atlanta Constitution’s story about his passing. What was mentioned, however, was the relationship between Coca-Cola’s inventor and fellow pharmacist Asa Griggs Candler, who summoned Atlanta’s druggists to his own shop to craft a tribute to Pemberton. “Our profession has lost a good and active member,” Candler told the newspaper. The pharmacists published a resolution honoring Pemberton, and they decided to attend his funeral services en masse, shuttering all Atlanta drug stores for the day in tribute to one of their own. Candler served as one of the “gentleman pallbearers.”

In the three years after Pemberton’s death, Candler (shown lower right) would prove to be more shrewd than congenial, buying up all the interests in Coca-Cola for a total investment of $2,300. With a flair for advertising and marketing, Candler turned Pemberton’s health tonic into an iconic global brand. In 1919, the Candler family sold Coke for $25 million to a group of investors organized by Ernest Woodruff. Asa Candler, who served as mayor of Atlanta, was an influential civic leader and philanthropic benefactor, bankrolling the founding of Emory University and what became Emory Hospital and helping to develop Druid Hills.

In the three years after Pemberton’s death, Candler (shown lower right) would prove to be more shrewd than congenial, buying up all the interests in Coca-Cola for a total investment of $2,300. With a flair for advertising and marketing, Candler turned Pemberton’s health tonic into an iconic global brand. In 1919, the Candler family sold Coke for $25 million to a group of investors organized by Ernest Woodruff. Asa Candler, who served as mayor of Atlanta, was an influential civic leader and philanthropic benefactor, bankrolling the founding of Emory University and what became Emory Hospital and helping to develop Druid Hills.

The secret formula for Pemberton’s concoction (which, urban myths notwithstanding, Coca-Cola staunchly claims never contained cocaine, or at least not more than a “trivial” amount in the early days) had been kept in a SunTrust bank vault since 1925. In late 2011, the formula was transferred to a new vault that is now part of the World of Coca-Cola museum.

All photographs courtesy Coca-Cola.