At one o’clock today, Atlanta city councilman Michael Julian Bond will honor Dante’s Down the Hatch owner Dante Stephensen at city hall with a City of Atlanta proclamation in honor of the restaurateur and jazz promoter’s “contributions to Atlanta’s cultural and business life.” Bond, a regular at the now-shuttered Buckhead nightspot, followed in the footsteps of his civil rights icon father Julian Bond, who was a regular at the original Dante’s Underground Atlanta location in the 1970s. “Dante’s was an Atlanta tradition,” explains Bond. “Locals and tourists alike flocked this unique establishment to experience a taste of the city in a communal fashion. This proclamation is our small gesture to Mr. Stephensen for four decades of service to Atlanta.”

Aside from selling tons of white wine enriched molten cheese for 43 years, perhaps Stephensen’s greatest legacy will be operating possibly the country’s only six-night-a week live jazz restaurant. He also nurtured two long-running jazz residencies, first, with the Paul Mitchell Trio from 1970 to 2000 and then the John Robertson Trio from 1989 until the venue’s closing on July 31. Mitchell played at both the Dante’s locations for 30 years until his death in 2000. Robertson, Mitchell’s student protégé at Morris Brown College, began working at the Underground location in 1989 and moved to his mentor’s piano bench behind the 1908 Steinway at the Buckhead location after Mitchell’s passing.

This month, Stephensen, Robertson, and his wife, acclaimed Atlanta jazz singer and Hatch weekend vocalist Rosemary Rainey reunited at the closed restaurant to discuss the venue’s unique jazz legacy. On this night, the now-covered Steinway sits in the dark and the wait staff who forever shouted, “Hot pot comin’ around!” aboard the ancient schooner have all disembarked. But Robertson remains nattily attired in his Dante’s work garb, a suit and tie. And still the consummate host, Dante excuses himself in the middle of the chat to take drink orders, grind beans and make a fresh pot of java for all.

When Rainey wistfully reflects about not getting to perform the classic Irving Berlin song Always in the excitement of the restaurant’s closing night, I was able to coax the singer into performing the torch song as Stephensen snapped on the stage lights and Robertson yanked off the Steinway cover for one last performance in the venue, just for Atlanta magazine readers. Click here to see the performance.

Q: When did your appreciation for jazz begin?

Dante: In high school. My father was a professional musician. Conductor, arranger, teacher, concert pianist. I’m told that at age four, I got up to the piano at home and with one finger, played My Country ‘Tis of Thee. In college, I played classical Spanish guitar and was in a group called The Stoics. We played folk. Music is in my blood. To my mind, jazz is classical music.

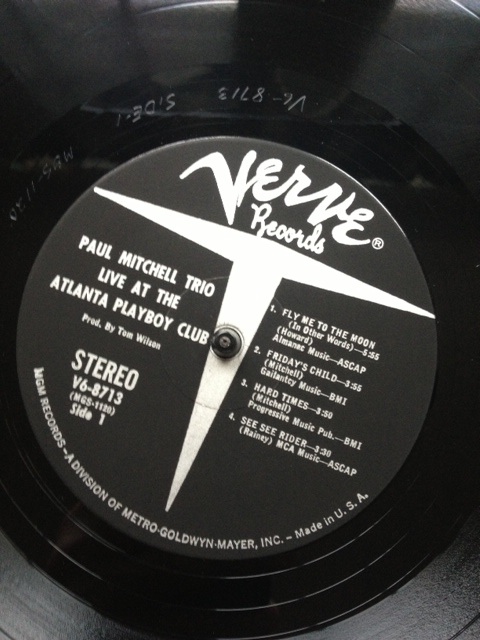

Q: Legend has it you first heard the Paul Mitchell Trio in the mid 60s when he was gigging at the Atlanta Playboy Club. This is about the same time Verve Records came to Atlanta and recorded the trio for the Paul Mitchell Trio Live at the Atlanta Playboy Club album. True?

A: Absolutely correct. I was a Playboy Club Key member. That meant I could go to any Playboy Club in the nation. Since I was a student going to school in Minnesota, I bought the key for 25 bucks. Dirt cheap. I became enamored with Paul and his trio, Laymon Jackson and Allen Murphy. They were playing in the Living Room, which was on the second floor of the club. I started going on a regular basis since I could get in for nothing with that key. Paul came up to me one night and said, “I see you in here a lot.” The Paul Mitchell Trio was always part of my plan for the original Dante’s [Down the Hatch] at Underground. I took Paul down there for the first time and we were standing in this unfinished basement — dirt floor, filthy, hadn’t been used since the 1880s — and I explained this ship concept to him. He thought I was completely crazy. But he ended up playing with us for 30 years.

John Robertson: (picking up the Mitchell Verve LP) To be honest, Paul didn’t much like this record. It was because of they way they edited together the tunes. They recorded the trio all week. The engineer had Verve money, you see. But instead of releasing the tunes as they were played on the different nights, they would splice a bass solo from one performance into the rest of another take of the tune on a different night. Paul had no creative control over it. There was no flow. A live performance should grow and breathe on its own.

Q: John, let’s fast-forward to 1975. You were a student of Paul Mitchell’s at Morris Brown College?

A: *Robertson:* I was an 18-year-old saxophonist in the band. Paul was one of the band directors. He arranged all the music. He was Mr. Mitchell. At one point, I learned about what he did at night and me and my friends went to Underground to see him play. I remember telling my friends, “This is what I want to do.” I got the Dante’s Underground gig in 1989 when Paul was playing up here at the Buckhead location. My teacher had become my friend. I had to learn to stop calling him Mr. Mitchell and call him Paul.

Q: Dante, let’s talk about 1970 Atlanta. We’re two years after Dr. King’s assassination and funeral here. We’re four years away from Maynard Jackson becoming mayor. Was there any negative reaction to hiring three African-American musicians?

A: The question never came up. We’ve always had black and white stockholders at Dante’s. Usually, it’s a white-owned or a black-owned business. We were always mixed. The concept of color never came up. Quite simply, they were the best. Oh, sure, we’ve had some up-tight people over the years. But we never had an incident in the restaurant worth a discussion.

Robertson: What also contributed to that was Paul Mitchell and his reputation. It went back to the 1950s. He played Paschal’s La Carousel which was a black hotel but the nightclub was integrated before integration. At Underground in the 70s, Mrs. King, Andy Young, Joseph Lowery, Julian Bond were all regulars.

Dante: We also hosted Isaac Hayes, Gladys Knight…

Robertson: Ramsey Lewis, Count Basie, Max Roach…

Q: Hold up, Count Basie?

Robertson: Yes.

Dante: I was honored just to be near him. He used to play with Paul. The Paul Mitchell Trio and the Basie band once played a double bill at the Fox Theatre. When Ramsey Lewis came to town, he would gig at La Carousel. But he would always come to the Hatch late to sit in with Paul. I remember one night Ramsey said to him, “Paul, I envy you.” Paul was shocked. He was a very humble guy. He said, “Ramsey, you’re famous worldwide. I’m just here in Atlanta. How could you even conceive such a thing?” Ramsey told him, “I’m loved because I’m famous. You’re loved because you’re Paul Mitchell.” It brought tears to Paul’s eyes.

Q: Dante, in 1973, you added record producer to your resume with the independently released Paul Mitchell Trio album, Another Way to Feel. How did that come about?

A: People were always asking if Paul had a record and the Verve Playboy record was difficult to find. So we made one. Believe it or not, we’ve never made back the money on that record and we’ve sold a lot of them over the years.

Q: Walk me through how you’ve not recouped the budget on a 40-year-old album you’ve been selling on vinyl, cassette and now CD since 1973?

A: Easy. It’s not inexpensive to make an album. It took a year to record. Plus, a proceed from each sale was given to the employee who sold each copy and the rest of the money went into a scholarship fund in Paul’s name. It’s earmarked for Morris Brown. That scholarship is still coming.

Robertson: (picking up a copy of Another Way to Feel) This is the good one. This is how they really sounded live. This album beautifully captures that.

Q: What happened to the other members of the trio?

A: Laymon passed away in 1993 but his wife was here for closing night. Allen is still alive and was here for closing night. He sang some emotional songs that had everyone in tears.

Q: John, you played six nights a week for 24 years, most of those spent with your bassist Edwin Williams and drummer Terry Smith. How does that connect you as a trio?

A: And we were still growing together. When you play together for that long, you eventually stop talking about it and just do it.

Dante: For the better part of 25 years, I’ve listened to John and his trio play six nights a week and I’ve never tired of it. John is a hidden master. Paul, I think, taught John how to play to the room, too. With a noisy audience, Paul used to pick out the noisiest person and stare at them while he was playing. Eventually, they got the message and, ultimately, he had the whole room listening to him. We also used to have to deal with the people celebrating birthdays who would sing Happy Birthday out of tune while Paul or John was playing. It was completely offensive. So I told them just to stop playing when that happened. The world is filled with assholes and a few of them came into the restaurant.

Robertson: That’s off the record.

Rosemary Rainey: The thing about Dante’s is that it was such a unique place; people would come for a lot of different reasons. So it was hard to get mad at the people. You had people who came for the fondue, we had people who would come for the music and the tourists came because they heard about the live crocodiles.

Q: John, You played that 1918 Steinway over there six nights a week. Did it become an extension of you?

Robertson: I used to play a 1906 Steinway but we lost it in the 2001 fire. It helps to have a great technician. The Steinway holds up. Most pianos could not handle being played six nights a week. They’re not built to. The Steinway is.

Q: Rosemary, how long have you and John been married now?

Rainey: We got married in 1990.

Robertson: And the Paul Mitchell Trio played at our wedding.

Rainey: Even before I met John, I would come down here to hear Paul and the trio play but I could never afford [the music cover charge] to sit on the ship. I was a student at Georgia State. I sat on the wharf. One night, Paul came over and got me and sat me on the ship. I was thrilled. I was majoring in business management but I spent all my time in the music department singing with the jazz band.

Dante: She still manages John extremely well!

Q: On closing night, what did you get to play that was important to you and the history of this place?

Robertson: I got to play Friday’s Child, one of Paul’s compositions while his daughter was here. She was the inspiration for the tune. Her mother had written the lyrics for it. As I started it, Allen walked in, grabbed the microphone and started singing. That’s all it took for the tears to begin flowing.

Q: What does the loss of Dante’s mean for jazz fans in a city where there aren’t a lot of rooms to hear jazz or pays jazz musicians a living wage, especially in the same summer when Churchill Grounds has had to close the Whisper Room?

Robertson: To have a residency here for two and a half decades has been beyond amazing.

Rainey: When we told people in New York, they couldn’t believe John got paid to play jazz in Atlanta six nights a week. You can’t do that in New York. It’s unheard of. This place is a part of our family. We were able to raise a family, send our first child to college and have money you could count on. That’s a big thing. It’s going to be a tremendous change.

Q: What’s next for the trio?

Robertson: I honestly don’t know. You can’t replace this.

Rainey: This was very special. As musicians, we didn’t have to pretend to love what we did here. We truly did. Before they tear this building down, we want to make a live recording here to document this time, this place and this music.

Robertson: We want to record the acoustics in here. The sound of this room can’t be duplicated. All the wood gives it a specific tone. This was all put together by hand. I like to think that in a room like this, where music was played for so long, in a way, the jazz is still here, all around us.