This story originally appeared in our January 2013 issue.

The phone rang in Mike Virga’s office in Union, New Jersey, one morning three years ago: “I hear somebody going, ‘I want some of that good Lioni mozzarella. Come on, sell me some. It’s me, Giovanni.’ I’m saying to myself, Who’s breaking my chops? I have no clue. But he’s talking like a Brooklyn guy. So I says to myself, In one minute I’m going to hang up. Then he goes, ‘You in front of a computer?’ I says, ‘Yeah.’ And he says, ‘Go to my website.’ So I do. Then I says, ‘Hey, Giovanni, how you doin’!’”

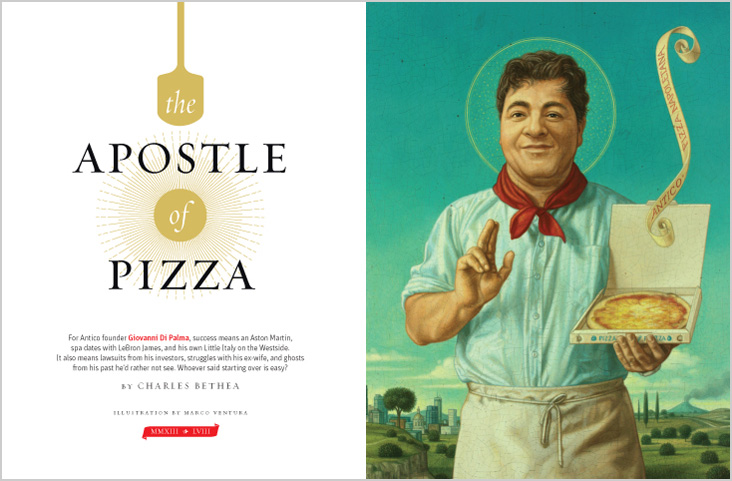

As vice president of Lioni Mozzarella and Specialty Foods, the nation’s biggest importer of di bufala mozzarella from Naples, Virga knows pizza. But Antico Pizza Napoletana was special. Zagat last year named its food among the best in our city, behind only Bacchanalia. “Believe the hype,” wrote the Saucy Server blog. “What’s there not to love?” asked the Cynical Cook. It seemed like a lot of fuss for a paper-plate pizza joint—and in Atlanta, Georgia, of all places.

Still, Antico’s owner, Giovanni Di Palma, was buying more cheese than most distributors do. Virga and his partner at Lioni, Charlie DiSalvo, had to meet this customer. “He was taking how many tins of ricotta?” Virga asked rhetorically. “Forget it.”

The cheese men have patronized famous pizzerias around the world and know an imposter when they see one. “I own a pizzeria for chrissake,” DiSalvo told me, finally at Antico for the first time on a chilly night more than a year ago. The white-and-tan brick bunker of a building off Hemphill Avenue, on Atlanta’s Westside, was steamy with bakery heat and loud with opera music amplifying the spectacle of Di Palma making pizza: It was theater as much as food service. Low benches flanked three long, wooden communal tables, with stools around a fourth, and all of them were filled with people eating, talking, and staring toward the open kitchen area. Like DiSalvo and Virga, those who weren’t yet eating watched and waited for a taste.

Twenty feet away, Di Palma worked his ovens as an aria climbed from the speakers. In a tight shirt that revealed a bulky, unseasonably tan upper body, he flamboyantly tossed dough, disseminated cheese, and sowed toppings, admiring his art. Eventually he set a hot San Gennaro—sausage, cheese, peppers, cipollini onions—before the Lioni men: “Forget everything else,” Di Palma proclaimed. “This is pizza.” On the wall behind him was a poster: “What It Takes to Be No. 1.”

For a minute, DiSalvo and Virga were silent: rapt consumption. Then came the struggle to find words: “The dough, the crust, the sauce, the sausage, the ambiance,” DiSalvo stuttered. “It’s like Naples. It’s a pizza factory where everything is perfect.” A bead of sweat trickled down his nose. For a moment he seemed almost sad. “We had to come to Atlanta to get the best pizza we ever had.”

Satisfied, Di Palma took off his apron and greeted a few regulars, one of whom called his pizza “sex on crust.” The maestro pizzaiolo has the face of an aging Baldwin brother after a debauched beach vacation—bronzed, puffy, good hair—and a New York–inflected voice that radiates street-level confidence as he tells stories. Like the one about how Tom Brady and Gisele joked that they wanted to adopt his twelve-year-old son, Gianluigi (also called Johnny), whom Arthur Blank’s daughter has a crush on: “Tom,” he said, “who’s gonna be my partner in the L.A. store, he had his arm around my son for thirty minutes! He said Johnny reminded him of what he was like as a kid. Gisele said he was the most beautiful boy she’d ever seen . . .”

Or the one about how he lived in his car, essentially homeless, just a few years ago. Or how he’s been shoe-shopping at Niketown with Mayor Kasim Reed. Or how he and LeBron James relaxed at a Buckhead spa together.

“No way,” a Georgia Tech student exclaimed after the LeBron tale. “I swear to God,” replied Di Palma. “It’s in the AJC.”

Turning from the incredulous kid and pointing to the workers behind him, Di Palma went on: “You see this whole dance going on back there? It’s like a symphony, and I’m the conductor.” Eight employees—including his brother, Giuseppe—returned our stares. “If I had to teach one person everything, it’d take three years.”

Back in the kitchen, Di Palma broke it down. “When I make a Margherita,” he said, grabbing prepared dough, “I put the cheese on first. I’m the only guy that does that.” He scattered the cheese. “This is the only place on planet Earth that has three of those in one building.” He pointed to his Acunto ovens, which, he explained, were custom-made in Italy. “Up in the dome, it’s a thousand degrees.” He pushed in the Margherita, after adding a few dollops of tomato and garlic and basil: “That pizza will cook in sixty seconds.” He removed it a minute later, admiring the mottled red-and-white pie.

“People say, ‘What’s the secret to your sauce?’” Di Palma went on. “I just crush these blood-red tomatoes.” He laughed. “People always want to know your secrets.”

Here at the corner of Hemphill and Ethel, before Antico opened its doors in 2009, before Giovanni Di Palma hosted a birthday party for Mayor Reed, before Di Palma even imagined turning this intersection just off of Northside Drive into Atlanta’s own Little Italy, a homeless man named Big Mike used to get high and collapse on the grass. One spring afternoon almost four years ago, Di Palma arrived and fed Big Mike pizza in exchange for his help: moving ovens, watching the parking lot, taking out the trash. Big Mike had never tasted pizza like this before.

Arthur Blank, Owen Wilson, Chris Rock, and (probably) your mother have followed, joining laymen and critics from Buckhead and Decatur, Nashville and Peru. They all gather inside the house that Giovanni built, and they mangiano under fluorescent lights, Vivaldi and Rossini piped in through the speakers. Some 700 pizzas are consumed here each day, in a place that doesn’t much look like a restaurant but is arguably Atlanta’s most beloved. Pizzas are about $20. No slices, no delivery, hardly any seating, and no apologies. This should not be a formula for success, but even the names behind Georgia’s best restaurants struggle for apt superlatives. The Diavola pizza, with its hot peppers and sopressata, “makes all other pizzas (and sometimes me) cry themselves to sleep at night,” wrote Cynthia Wong, formerly of Empire State South, on the Chefs Feed app. Peter Dale, of the National in Athens, called Di Palma’s Margherita pie “simply the best pizza this side of the Mason-Dixon line.” “It’s like dining in his basement,” Kevin Rathbun, chef and owner of Rathbun’s, Krog Bar, and Kevin Rathbun Steak, told me. “You’re right there in the mix of it all. I thought it was a brilliant idea.”

But if success has many fathers, success in the pizza business evidently has many sons. Insolent sons, if you ask Di Palma. Coincidentally (or not), at least two of the newest arrivals on the local pizza scene— Ammazza in the Old Fourth Ward and the short-lived Fuoco di Napoli in Buckhead—trace their roots to Antico. The owners of the former served as Antico franchise consultants for a year, while the owners of the latter were some of Di Palma’s earliest investors. Don’t expect Di Palma to darken Ammazza’s door anytime soon. As for Fuoco, he sued its owners, claiming they stole his ideas, right down to the open kitchen and rustic dining area. Di Palma isn’t just on the attack; he’s had to play defense, too: The lawyers for a man who won a default judgment against Di Palma in 2009, stemming from a failed dot-com, are eager to see their client finally paid. And to top it off, Di Palma’s ex-wife sued him last year in a contentious custody battle involving their son, whom she says she hasn’t seen in eight years.

So the guy who was “making every pizza myself” just a couple of years ago is now surrounded by an eager flotilla of publicists, attorneys, and advisers. The excitement of his newest venture—creating his own version of Little Italy on Hemphill, complete with a chicken restaurant and limoncello bar, using Antico as the anchor—is tempered by the ever-increasing price of success. It’s an unwelcome, if not unexpected, levy that comes in many forms. Even his often-discussed dream of opening Anticos around the world has been shelved, since he sold most of the out-of-state franchising rights to an investor. The sale made a comfortable Di Palma far wealthier, but he doesn’t seem sure if his singular triumph as a businessman has made him happier.

“The way it’s evolving has become sort of bittersweet for me,” he said. “I wish I could just go back to making two pizzas at a time, to be honest with you. Honest to God I do. It was more fun back then. It was simple.”

“I don’t want to tell you how to write your story,” Di Palma said one night at his Buckhead villa. He sat beside his pool, in full view of his Aston Martin and Range Rover—since upgraded—by a fire that lit his face like a wax mask. “But I think you should begin with me in the car on a cold night in New York. People are gonna be like, ‘Holy f–k!’” Di Palma called over his assistant, who refilled two glasses with Sangiovese.

Every success story needs an epiphany, a moment when the hero, lost and wandering in the dark, sees the light. Di Palma’s epiphany came on a transatlantic flight, in the form of the movie Wall Street. Decades ago, friends actually called him “Bud Fox,” the corrupt stockbroker played by Charlie Sheen, “because of my resemblance.” In the film, Fox’s father gives him advice: “Stop going for the easy buck and produce something with your life.” Watching it for the fiftieth time, while flying to Italy in 2005, that line finally hit home.

“When I heard it,” he explained, “I said, ‘That’s the message: kid trying to get rich on Wall Street ends up broke, back in his blue-collar father’s Impala.’”

He was traveling, as the story goes on Antico’s website, “to make a family contribution to the famous Commune Basilica, built in 300 AD, where Felice and Louisa Di Palma”—his grandparents—“were married.” Di Palma glided over the details of his life: One of eleven kids. Grew up without much money in western New York. Visited Italy every few summers. Went to Daemen College near Amherst, where he played on the basketball team. Bartended a bit. Moved to Florida, where he handled baggage. Worked as a stockbroker. Tried and failed at selling things, like cigars. He married a woman in Europe; they divorced after having Gianluigi.

Cimitile is a small town fifteen miles northeast of Naples that produces San Felice flour, coveted for withstanding the extreme heat of pizza ovens. Decades ago, Di Palma’s grandfather had worked as a baker and restaurateur there. When Di Palma visited in 2005, he said, he was introduced to Innocenzo Ambrosio, who ran the flour mill. Ambrosio, in turn, took him to the most famous pizzeria in Naples, Il Pizzaiolo del Presidente, where he met legendary pizzaiolo Ernesto Cacialli. “To get the access I got,” he said, “you have to have a deep level of trust.”

Di Palma returned seven times over two years, he said. Cacialli, now deceased, taught him the secrets of Naples-style pizza. He studied many types of flours. He entered prestigious pizza competitions. And he began importing ingredients.

All those trips to Italy were expensive: “Some twenty grand,” he said. That was a lot for a guy whose job then was “selling logo items to luxury resorts.” He’d sold his Volvo SUV, his golf clubs, fancy watches, and left an apartment he couldn’t afford. He’d even cashed his son’s college bonds. In late 2007, he slept in his beat-up Dodge Challenger on a freezing night in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. His seven-year-old son was with him, and he considered their dinner options. He needed enough money for gas to get to a meeting with potential investors the next day. So he and Johnny ate Happy Meals in the backseat.

We walked inside his tastefully decorated villa, where a picture of him and his son posing with Arthur Blank was prominently displayed on a side table. Di Palma presented a copy of an AJC story that described his spa outing with LeBron James and Jay-Z at Buckhead’s St. Regis hotel: “After the two entertainers admired Di Palma’s ride—a drop-top Aston Martin—all three decided to rejuvenate with facials and massages at the Remède Spa in the St. Regis. Noted Di Palma: ‘Real men do spa!’” He was the story’s source.

Holding his wine, but not drinking it, Di Palma returned to Antico’s origins: In late 2007, he began researching pizza markets outside New England. In smaller cities where start-ups were easier, higher-quality ingredients would be harder to obtain. Atlanta, a metro area of 6 million with no serious pizza scene (“Mellow Mushroom? Come on”) but a low cost of entry, was a good compromise. He said he had around $100,000 to invest: “I went all in with everything I had and didn’t have. I was surprised no one, not even my family, would invest in my pizza plan. But when you get to that darkest moment, you just say, ‘You know what, nothing’s gonna stop me.’”

He found a location on Hemphill, near Georgia Tech: a sandwich and pastry place called Jaqbo Bakery & Cafe. Cousins in Marietta put him up in early 2009 and also introduced him to Dennis McDowell, a small-bank investor who, along with his family, invested $409,000 in the start-up, according to McDowell’s attorney. Di Palma said he closed on the bakery in two weeks, paying $115,000. The huge ovens cost about $9,000 apiece and another $4,000 each to ship.

It was a plain little lot near a drab intersection at the edge of a harried Westside neighborhood. But it fit what Di Palma said was his plan: to open a wholesale and retail pizza business with low operating costs—nothing fancy, minimal seating. Mostly he would sell prebaked pies to supermarkets.

Di Palma named it Antico because it’s old school, Napoletana for its origin, and opened for business in September of 2009. And the competition? In his view, there was none: “Creative Loafing had the eleven least influential people in Atlanta, and [Jeff] Varasano was one of them,” he said, referring to the owner of Varasano’s. “He couldn’t convince anybody that he was really who he said he was as far as making pizza. And then, two weeks later, Antico was on the cover.”

Meanwhile the kids at Buckhead’s Warren T. Jackson Elementary didn’t believe that his son had met Tom Brady (through one of Di Palma’s business partners) and Justin Bieber (through Di Palma’s pal Arthur Blank). So Johnny—who transferred to a pricey private school last year—showed them the newspaper stories about his dad. “He’s a smart kid,” Di Palma said. “He knows how to spell inheritance. That’s a big word.”

Di Palma still returns to Italy. “I’ve gone twice in the past three years,” he said. “I’ve become a celebrity there. They treat me like a king. I’m the only American to be written up in the Naples newspaper about pizza! I’ve made their flour famous!”

To understand someone, you talk to his friends. This becomes essential when the details of the person’s story are as elusive as Di Palma’s. First he was forty-three, then he was in his “late forties.” (His brother says he’s fifty.) First he was reminiscing about sleeping in his car in New Jersey, then it was in New York. His former girlfriend told me that his mother is dead, but he told me she’s alive. In recounting dinner with the Lioni cheese men at Chops, he told me they ran into Denzel Washington, who complimented his pizza. But the cheese men had no memory of this. Nor did Daemen College’s athletic director, Bill Morris, have a record of a Giovanni Di Palma playing on its basketball team—or a John DiPalma, the name Antico’s founder was known by in college, then while working in Chicago in the 1990s, then during his first marriage in Florida and Rhode Island; court records also use this name.

When I initially asked him for names of friends I could speak with, he waved me off. “That was a long time ago,” he said. So I began searching. First came an ex-fiancée whose name I found in a glowing 2010 CNN.com story about Antico, which began: “No pizza maestro worth his sauce will reveal his secrets.” When I reached her by phone, she didn’t say much, but did offer this: “You won’t get him to open up. The mystique adds to the allure.”

Within weeks of opening in 2009, Antico was going gangbusters. Lines went out the door. Di Palma couldn’t make more than two pizzas at a time. He needed help. He moved a marble table into the middle of the kitchen, in full view of the customers sitting in the dining area surrounded by cans of tomatoes and sacks of flour, under a Ferrari banner, an Italian flag, and a TV playing soccer matches. The table expedited operations, but it also put him and his workers on display.

“When I put the marble table in the middle, it not only created a stage and a show unlike anywhere else, it enabled us to make six pizzas at a time and use all three ovens,” he said. “The six-pizza system that I created has never been done before in the world.” To spend time with Di Palma is to constantly be reminded you’re in the company of a history maker, though he’s quick to balance his loftier boasts with more pedestrian declarations: “I’m just a baker.”

What Di Palma said were his earliest expectations—to make enough money to cover his rent and car payments—soon seemed almost laughably low. In Antico’s first year, he told me, he grossed $1.2 million. In 2011 it was $4 million. Di Palma was defying every conventional rule about the restaurant business, and it was making him rich.

It was also making would-be investors take notice. In May of 2011, he sold the franchising rights to Scott DeSano, who at one time was the head of stock trading for Fidelity Investments. (DeSano was introduced to Di Palma through Hugh Connerty Jr., the founder of Longhorn Steakhouse, whose sons opened Ammazza after working as franchise consultants for DeSano.) Although Di Palma said the deal—worth roughly $4 million—guaranteed him a seat on the board, royalties on every pizza sold worldwide, and a 10 percent ownership stake, he was no longer the decision maker in Antico’s future. Yes, he retained ownership and control of the Atlanta operation, but outside the markets of New York, Washington, D.C., and Miami—territories that Di Palma retained options on—the future of the Antico concept was now in the hands of a man who did not know pizza. DeSano had never owned a restaurant, much less an idiosyncratic creation like Antico.

“I’d fended off $10 million deals and $15 million deals,” Di Palma said. “I did this deal because it sounded like a meaningful partnership.”

And still a profitable one. “The valuation of the company was $50 million!” Di Palma said. “My royalty payments were to be in excess of $1 million a month after five years. So I’m human. I grew up poor. I could take care of a lot of people with that kind of money. And I didn’t really have a lot of risk, because I had protected Atlanta and my market.”

Last fall in Nashville, DeSano opened the first pizzeria of what could be an Antico-inspired international franchise. Just like the first one did in Atlanta four years ago, the new outpost took the Music City by storm. Foodies couldn’t stop raving about it. A self-described “pizza snob” opined under a five-star review on Yelp, “I can assure you—you have NEVER had a pizza like this in Nashville—or, dare I say, nearly anywhere else.” The reviewer for the Nashville Scene, who visited twice, wrote, “We left nary a crust or crumb.” The Nashville menu is almost identical to Di Palma’s Atlanta pizzeria. So is its logo, which evokes a faded passport stamp. And so is the place’s set-up—from the three Acunto ovens (each named after a different Italian saint) to the open kitchen and communal tables. However, the words inside the logo and out front are not Antico Pizza Napoletana, but DeSano Pizza Bakery Napoletana.

“Ultimately, would I have liked to see [the Nashville pizzeria] be Antico?” Di Palma said. “Yeah, but there’s a part of me that says if it fails, it doesn’t blemish me. To share my culture and what I created all over America would be nice, but I realize I can’t be in all those places.”

DeSano wouldn’t comment for this story.

On a fall afternoon, Di Palma shows me his new property on Hemphill. A residential lot to the right of Antico will become a 2,000-square-foot bar (limoncello and other Italian liquors), coffee shop (no sugar or cream, Italian-style), and gelateria (a half dozen Italian flavors, but no samples) that also serves Italian street food (sausage sandwiches and fried pizza). To the left, an old catering company with a huge kitchen will be the heart of Gio’s Chicken Amalfitano, an Italian-style fowl operation run very much like Antico: pay up front, no waiters, a half dozen choices. There is still much work to be done, like remodeling a dilapidated house into a hip, one-story bar that includes a romantic piazza with outdoor seating (“for people-watching”) where bums once slept. “This used to be a scary neighborhood,” Di Palma says. “Then I showed up.”

Unexpected problems keep arising, however, for the neighborhood’s savior: A walnut tree drops heavy nuts where Bar Antico’s patrons will sit, listening to Dean Martin under the stars. “Nuts,” says Di Palma. “I have to deal with nuts.”

Overseeing much of the construction is Di Palma’s older brother, Giuseppe. Giovanni comes from a large family—ten siblings, he says—but he’s estranged from all but Giuseppe. Why?

“I was always the guy that when we all went to dinner, I paid. When people needed a loan, I loaned them money. I always take care of everybody. When my dad died, I took care of my mother. But when I ended up on hard times, they turned their backs on me.”

Paul DiPalma, one of Giovanni’s siblings and a plumber living in western New York, seemed to all but confirm the rift. “I haven’t heard from John in five years,” he told me by phone, before hanging up. “No one in the family has.” Except, of course, for Giuseppe, Antico’s director of operations.

“I think it was right before Christmas [a few years ago],” Giovanni tells me, “and Antico had just won a bunch of awards and there was lines on the street, when [Giuseppe] called me. He’s a tough guy and I could hear in his voice that it wasn’t good and I was like, ‘What’s up, what’s wrong?’ He didn’t have a car. He was staying in a motel. So I said, ‘Man, you picked a really good time to be broke. Go to Western Union. I’m sending you $500. Get on a plane or a bus and come to fucking Atlanta, Georgia. You’re good.’ And that was it. He’s been here ever since.” Giuseppe’s account differs on several points—he wasn’t staying in a motel, he says, and he had some money in the bank—but he confirms that his younger brother invited him to Atlanta to help run a pizza place.

The brothers look alike, which has led Giovanni to establish some social rules with Giuseppe: “If [the physical similarity] is going to get you a chick,” Di Palma says, “you can go along with it to a point. But at the end, you don’t own Antico.” (Giuseppe: “A pretty girl walks in and what are you gonna say? ‘No, Giovanni’s not here’?”) “See, my older brother has a lot of pride, and he’s had to eat humble pie. I haven’t decided what I’m going to do with him yet. He doesn’t have to be under my thumb forever. I might give him his own Gio’s. He’s not really an idea guy.” And the rest of his family? “When I’m ready, I’ll buy them plane tickets and I’ll get them down here and we’re going to share it. If they want a job, they can have a job. How can I hold a grudge? I made it and I’m happy and my life is good.” Giuseppe is optimistic: “People forget the bad stuff, don’t they?”

Last year, though, the ghosts of Di Palma’s life before Antico came calling. In 1999 Di Palma and some associates incorporated a company that became Webscape Holdings and soon after sought investors. Webscape Holdings was an IT company, or was supposed to be, according to the business plan put together by John DiPalma, listed as cofounder and director of financial affairs. Even for the era in which it was written—the boom years before the dot-com bubble burst—the plan is remarkable for its opacity. It was a “business

. . . developed by former Wall Street and Internet executives” that “specializes in developing innovative ideas and strategies for simplifying investing and providing scientific solutions via the Internet.” Its two main tools, according to the plan, were websites called “theguru.com” and “doceinstein.com.” The success of the endeavor hinged on an “exclusive relationship” with Dr. George P. Einstein, a direct descendant of Albert Einstein.

Claiming he had been defrauded—two different kinds of fraud were alleged in a complaint: “fraud in the inducement” and “mismanagement, waste, and fraud in the transfer of corporate assets”—one of the investors, a former professional baseball player named Doug Jennings, filed suit in 2001. Di Palma didn’t show up to defend himself. In a 2009 default judgment, Di Palma and four other defendants were ordered to pay Jennings a sum eventually totaling some $348,000, with interest. “I didn’t have the money to fight it or I would have won,” Di Palma says now. “When the meltdown happened, everybody lost everything. Our shareholders got twenty-five cents on the dollar, but Jennings said no.” Last year Di Palma’s attorneys settled the judgment for $180,000, according to Di Palma. (Doug Jennings’s Atlanta attorney, Christopher Porterfield, says that number is incorrect but won’t disclose the terms.)

Last year Di Palma also found himself in Fulton County family court, battling his ex-wife, a Pennsylvania mother of four who had finally tracked him down in Atlanta. Shannon Salvino argued that the man she’d only known as “John DiPalma” had denied her access to their son, and that for years she had not known where they were. She even set up a website in 2009, featuring a picture of a younger Di Palma below a banner that read, “Have you seen this man? He’s taken my baby. Please help me.” She also created a YouTube montage titled “Johndipalmaontherun.”

After Salvino missed a custody hearing in May of 2012, Fulton County Judge Gail S. Tusan dismissed her custody complaint for “failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted” and even ordered her to pay Di Palma $117 per month for back child support, and to reimburse him for the $11,000 he spent in attorney fees. (Court documents prepared by Di Palma’s attorney show that Di Palma’s gross monthly income is $47,666.67, while Salvino’s is $1,256.67.) The website came down and Salvino returned to Pennsylvania. She says that Di Palma and his lawyers—including the high-profile Atlanta family practice attorney Randy Kessler—were open to letting her see her son, if she agreed not to speak negatively about her ex-husband. A letter to Salvino from Kessler confirms this offer, but as of November, Salvino had not accepted it.

Meanwhile Di Palma has turned to a less conciliatory approach with former Antico investors. According to Dennis McDowell’s lawyer, Cade Parian, McDowell’s family partnership invested $409,000 in Antico in 2009. Two years later, in May of 2011, Di Palma bought them out, agreeing to pay the family at least $125,000 in royalties each year, according to a settlement signed by both parties.

By the end of that year, the McDowells and other partners had opened Fuoco di Napoli in Buckhead. In April of 2012, Di Palma filed an intellectual property suit in state court against the restaurant and the McDowells. Fuoco, Di Palma argued, “attempts to serve pizza end to end in the exact manner of Antico Pizza.” It went on, after quoting much of the positive press Antico has received (some from this magazine): “Defendants have intentionally knocked off Antico’s trade dress, including the wood-burning oven, rustic communal wooden-styled tables, the strategically placed wooden boxes and crates throughout the store . . . the open-styled kitchen for customers to view the pizza chef’s preparation . . . and the playing of similar music throughout the restaurant.”

The McDowells appeared surprised. “This [suit] was unexpected after all that we did for him and his business,” emailed co-owner Lori McDowell. The family partnership in turn sued Di Palma for $31,250 in unpaid royalties. Parian was dismissive of Di Palma’s argument, characterizing it in an email as, “I invented the Neapolitan pizza, and you can’t have it.”

Although Parian says that family members are still pursuing money they claim Di Palma owes them, Fuoco itself shut down in October, after less than a year in business. According to Lori McDowell, the closing had nothing to do with Di Palma’s suit. “It was a business decision,” she said. The next month, Di Palma dropped his suit, which by that time had moved to federal court. “Mr. Di Palma’s goal when he filed the lawsuit was to protect Antico’s brand and reputation and also let Atlanta know that there is no relationship between Antico Pizza and Fuoco di Napoli,” Di Palma’s team said in a statement. “That goal has been fulfilled.”

While Di Palma doesn’t make pizzas as often anymore (he says he’s there most weekends, though), Antico remains a destination for the rich and famous, along with the rest of us. Ludacris dropped by last year, as did Young Jeezy’s entourage, and some of the Real Housewives of Atlanta. Former Atlanta Braves closer John Rocker came by a few days after Christmas with one of Di Palma’s exes. Owen Wilson signed a wooden paddle by the door. Arthur Blank, the Home Depot cofounder and Falcons owner, is a regular. He told me, barely able to contain himself, “I’ve had every kind he makes. If I went there more often, I’d look like a pizza.”

Di Palma is fond of talking about how healthy his product is—“eaten in moderation, of course”—but Antico pizza and its particular by-products, both nutritional and interpersonal, have aged him.

On this day, the first day of fall, he appears at half past eight in the morning at the White House, a white-collar breakfast place in Buckhead. There he is: hoodie, designer jeans, fancy sneakers untied, half-hugging a handful of waitresses, mostly old black women who coo to him and smile. He makes a winking joke at my expense to one—“I usually meet someone better-looking for breakfast”—and picks up a menu. Sitting at a back table, his sunglasses are still propped on his forehead, where wrinkles have accumulated over the past year, along with bags under his eyes.

There’s a saying in the restaurant business: Come with nothing, leave with nothing. It’s meant for menial workers, who might take something that’s not theirs. Giovanni Di Palma came to Atlanta with close to nothing—failed businesses and relationships behind him—and now he has it all: the best lawyers money can buy, a nationally renowned restaurant, a handsome son at a top private school, his pick of younger women. He recently bought a Mercedes G-Wagen that has increased his profile even more. (“People who’ve known me for two years treat me like a different person,” he says. “All of a sudden it’s ‘Mr. Di Palma.’”) And new restaurants will almost certainly keep the buzz going. His publicity and marketing strategy, he says: “Just turn the lights on.”

We head to Antico, where the crowd is beginning to arrive. Di Palma rarely wears the baker’s costume (neck scarf, full apron), as he did when he began. He just nods to his guys, picks up the dough, stretches it, and tosses it behind his back to one in the theater-kitchen. “You can’t fake it,” he had said months earlier. “Everyone is watching.”

Di Palma checks the freezer, has someone bring him Italian coffee and a pastry, and begins talking even more rapidly than usual. Here come the claims: “I’m the only guy in Atlanta with this watch,” he says to his high-profile publicist, Liz Lapidus, and her young assistant, who have just arrived. Lapidus oohs. It’s a Hublot with a Maradona design. Di Palma is hosting a dinner for Hublot brass at Gio’s Chicken, soon after it opens next door to Antico. Di Palma and his team walk over.

His new chief financial officer, Andrew O’Connell, a veteran of Reynolds Plantation who says he can “open a place like this with my eyes closed,” is standing beside him as Lapidus runs down her marketing strategy list (topics: Hublot party, Scoutmob, Chefs Feed app, Instagram, PR for Gio’s) on a prep table. Di Palma responds while making chicken.

“I can’t put my name on Scoutmob,” he says of the online deal site with a sour face. What about Chefs Feed? (Tagline: “Where do the best chefs eat when they’re not in their own kitchens?”) “Yes,” he says. “Definitely.” Motown or the Rat Pack soundtrack? “Tough one. Probably Rat Pack.” What about these logos? “Those lemons are too big,” he says, pointing to a beautiful design that doesn’t emphasize chicken nearly enough. “This isn’t a produce stand in South Georgia.”

All the while, Di Palma is toying with a new chicken recipe. In his element—creating an original menu out of thin air—he is ebullient: “I think I might have discovered the next big thing,” he says, tasting a dish that incorporates Sardinian olives, onion, and breadcrumbs. “Right in front of your eyes. Magic.”

His employees eat the hot, oily chicken straight out of the dish in which it was prepared. A familiar look appears on their faces: It’s the look of the Antico crowd, the look of lotus-eaters. Giuseppe is in the next room, telling half a dozen laborers how the cash counter should be designed. It will be large.

“We’ll need to keep confetti cannons in storage,” Di Palma tells O’Connell a short time later, after his CFO has finished begrudgingly washing dishes, at Di Palma’s behest, in the huge kitchen. “We’ve got to be prepared to celebrate at all times. Buy out the cannon company,” he continues, without looking up or making clear whether or not he’s joking. “Companies disappear.” O’Connell takes note.

Conversation lulls and Di Palma mentions that he’s planning to propose to his current girlfriend on the balcony at Bar Antico, which hasn’t yet been built. O’Connell’s ruddy Irish financial officer’s face turns white: “Prenup!”

Di Palma grins. “He doesn’t believe in love!” Then the baker turns back to the heat of the ovens.