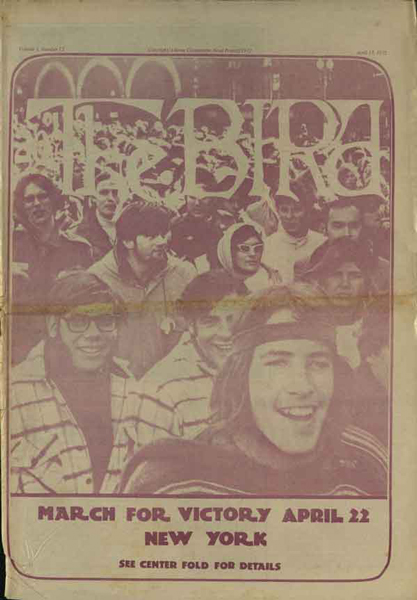

Copyright "Great Speckled Bird." Courtesy Georgia State University

This article originally appeared in our December 2011 issue.

An aging hippie limps into Aurora Coffee and takes a seat beneath the concert flyers that cover the wall. He drops a plastic grocery bag onto the sticky countertop, lifts out a pile of old newspapers folded in half. The hippie has sunken cheeks and a gray beard, a thick mustache and a full head of short, graying hair. He’s wearing tennis shoes and a T-shirt with a cartoon bird on the front, its wing curled into a fist. His papers—well, they’ve yellowed over the years, and the ink has faded, the pages turned brittle. He bends one of the copies carefully at the spine.

“If you open them too fast, they’ll tear,” Steve Wise says, slowly folding back the first page of a copy of the Great Speckled Bird. This issue is forty-two years and seven months beyond its publication date. With pride, he points to an essay he wrote titled “Southern Consciousness.” Wise had written: “Southern Consciousness is based on an impulse that originates in the very depths of the Southern soul, in the intense and profound feelings for the rootedness of a society, no matter how much corrupted . . . Liberate the South!”

The Bird was first published in 1968, during one of the most tempestuous times in the history of our country—especially the South, which was still in for a lot of liberating. It was the city’s first underground paper and became one of the biggest and most widely read in the region, with 27,000 readers at its peak. When Mike Wallace profiled the Bird on 60 Minutes in 1971, he called it “the Wall Street Journal of the underground press.”

Half a lifetime before Twitter and Facebook, the Bird acted in the same fashion, and in the spirit of what social media has become: a tool for mobilization, a civic rallying cry, a chronicle for news that the mainstream media chooses not to cover, and, above all, an outlet where anyone can have a voice. You could walk into its offices, manuscript in hand, and have your story, poem, or artwork published.

Wise, a Virginia native then in his mid-twenties, had an even thicker beard and hair down to his shoulders. As a member of the Southern Student Organizing Committee (an activist group that focused on civil rights and opposition to the war), and a new leftist with a history degree from Emory, he hung out with the Bird staff in a three-story house on Fourteenth Street across from where Colony Square now stands. A collective of writers, photographers, poets, and cartoonists, they banged out copy on typewriters, cutting and pasting pages on layout tables. They called the house the Birdhouse. Wise wrote about music and politics, edited stories written by anti-war GIs, sold ads, and even took rucksacks full of 300 copies to Lenox Square—then an outdoor mall—where he sold the paper for twenty cents to weekend shoppers and teenagers, which helped supplement his meager staff salary of less than $50 a week. Several times he tried to sell a copy to one of the Bird’s favorite targets, Ralph McGill, outside the office of the Atlanta Constitution. McGill did not buy.

The Bird is one of the most fascinating and most forgotten artifacts of Atlanta culture. It was printed mostly weekly from late 1968 until mid-1976, sold by subscription for about $15 a year, and hawked on the street. The police harassed the vendors who sold the paper and the hippies who bought it. The Bird called the police “pigs.”

The paper covered “news you’re not supposed to know,” according to its own lore. It tracked national stories like the Vietnam War and President Nixon and the death of Martin Luther King Jr., as well as city issues such as police brutality, the garbage workers’ strikes of 1968 and 1970, and transportation. It featured exposés on Georgia Power and dogged Mayor Sam Massell, printing the “Slumlord List” in 1971, which cataloged the city’s biggest owners of indigent property—a roster that the mayor denied existed. One of its most influential stories, “Peachtree Creek Is Full of Shit,” was a three-page investigation about E. coli and feces pollution and the nascent environmental groups that were trying to get anyone to pay attention.

The Bird was the first paper in the South to seriously cover ecology. It also discussed health food, nurtured the local gay and women’s lib movements, and sent reporters to progressive rallies and concerts and courthouses. It encouraged conscientious objectors and experimentation with illegal drugs. Though there were a few black writers, the staff was mainly white—largely because of separatism in the black liberation movement, say former staffers.

When the Bird’s first printer stopped the presses because of political pressure, two staff members drove a VW Bug all the way to New Orleans just to publish one issue. In 1972 the Bird’s offices on Westminster Drive near the Atlanta Botanical Garden were firebombed—destroying archives, artwork, posters, furniture, and production equipment. No culprit was ever prosecuted. The paper did not stop publication then, either.

Copyright "Great Speckled Bird." Courtesy Georgia State University

State Senator Nan Orrock, who represents the Thirty-Sixth District and is a founder of the Women’s Legislative Caucus and Georgia Working Families Legislative Caucus, was one of the Bird’s six founders. She wrote and edited copy and helped set type. “I came out of progressive political work, opposition to the Vietnam War. I [came] of age politically in the civil rights movement,” she says. “The motivating force was to create an alternative source of information [to what] we could find in the Journal and Constitution. Being a founder, and working on it, was a political act.”

On the heels of a successful exhibit during the 2011 Decatur Book Festival and a project to digitize the Bird’s catalog by the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University, the paper’s history will be featured in a GSU traveling exhibit funded by grants, which will visit colleges across the state during the upcoming year. Students will browse the digital archives and learn that the paper’s name was plucked from a hymn popularized by Roy Acuff, which references Jeremiah 12:9: “Mine heritage is unto me as a speckled bird, the birds round about are against her; come ye, assemble all the beasts of the field, come to devour.” They’ll see the paper’s logo was a cartoon bird with large talons, its wing raised in a valiant fist. The students will also learn that without a good business model, and with Creative Loafing stealing some of its ads, the paper folded in 1976, briefly resurrecting as a monthly in 1984.

“Young people loved its point of view,” says Barbara Joye, who wrote for the paper off and on for about four years; she still lives in Little Five Points and volunteers for Atlanta Jobs with Justice, an organization that advocates for workers’ rights. “They loved the music and the accepted wisdom. The hippie culture and the political activism overlapped. It was the sixties. Every five minutes, there was something to be upset about—some new revolution, some civil disobedience. The Bird was a great experiment in democracy. Everyone on staff rotated jobs every few months. I started writing about the women’s movement, and the gay movement. I wrote about the Black Panthers. Marched with the garbage workers. We were these wild-ass hippies.”

Copyright "Great Speckled Bird." Courtesy Georgia State University

In the Bird, objectivity was a myth perpetuated by the capitalist press. The paper was often funny and, even more often, angry as hell. Headlines read: “This Page Is for Freaks,” “Gay Power on the Strip,” “Injustice!,” “United Farmworkers in Crisis.” Covers were splashed with determined ink like “Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker!,” with images of raised fists and malicious caricatures of politicians. A two-page comic showed a man defecating on passersby. No story the Bird ever told through images or words had two sides.

“The Bird was one of these papers in the South that took off in an environment that was not conducive to left-wing protest. It may have meant more to its readers in that sense. I bet you a lot of people read it very carefully, and very excitedly,” says John McMillian, a GSU professor and author of a book, Smoking Typewriters, about the sixties underground press in the U.S. “It was one of the best underground papers. A lot of the people who worked on it, they’ve stuck around Atlanta, continued to be plugged in to the local activist community.”

Two aging hippies sit across from each other at a wooden table near a purple porch swing in front of a shaded house in Virginia-Highland. Between them is a large binder filled with copies of the Bird. The quiet street out front is slick with rain.

“When my husband and I came here in 1967,” says Stephanie Coffin, “almost every major city had an underground paper. There was not a big one in the South, or here—there was a huge gap.” She has short salt-and-pepper hair and warm eyes. Her husband, Tom, is sitting near her at the end of the table. He’s thin, with a long white beard that forms two points, and short hair. He named the Bird and helped start the paper, after helping launch a publication as an Emory grad student called the Big American Review. “It was primitive in the beginning,” Stephanie says. “We were just a group of people who had an idea.”

Later, Stephanie and Tom had two children. Tom, who dropped out of Emory to work on the paper, earned his Ph.D. in forestry in Athens; Stephanie taught English as a second language at Georgia Perimeter College. Now they are an old married couple, both in their sixties, who often pedal around town on their recumbent trikes.

“We were embedded in the city,” Stephanie says. “That was real journalism. We really wanted a revolution. There was just a hot energy of people focusing on getting these messages across. That was a life-defining experience.”

This article originally appeared in our December 2011 issue.