![]()

Around 586 B.C., the Israelite people had been conquered. Taken captive by the Babylonians, their earthly kings of lust, covetousness, pleasure, and greed had let them down. They lost everything they had, and were headed for years of slavery under a new foreign and brutal king. As they were marching to their new land of enslavement, they sat down by the rivers of Babylon and wept. They remembered their homeland and much better times.

In essence I did the same thing. When I first began writing this book, I was sitting on a rock near a foreign border, covered in sweat, blood, and dirt. I was looking back and thinking that if the bank investment would have been successful as planned, I would not be looking across a river and thinking of everything that was lost, and longing for better times of the past. While on the run for my life, I sometimes felt enslaved in this dark and evil world. I often dreamed of times past; times of laughter, happiness, love, family, and friends.

I came to realize that every day is a gift, and if I am alive at the end of each day, I ask God to help me be one step closer to completing my unfinished work of making full restitution to every one of my clients and to my creditors. I have had to relearn how to take one day at a time; pursue the love of the Creator; and embrace, connect, and protect His creation, especially His children. I still trust God to use me even in the darkest and most difficult of places, and with the most hostile of persons.

—Aubrey Lee Price, from the preface to The Inglorious Fugitive, his unpublished memoir

The last memory Hannah Price has of her father before he vanished is waking up to him praying over her. That itself was not unusual; Aubrey Lee Price had always been a demonstrative Christian. In the late 1990s he’d been a pastor at a small Baptist church in Griffin, Georgia—and after that, at Clear Springs Baptist Church in Johns Creek—where he tithed, mentored young congregants, and led mission trips to South America to build churches and distribute clothes to the poor. A Christian practices his faith through acts, Hannah’s father believed. A Christian also thanks God for the blessings bestowed on him, and Lee Price—no one called him Aubrey—was rich with them: four children, a wife, and a position of stature in the secular world.

For the past four years, Price had run his own multimillion-dollar investment firm, PFG. More than a hundred clients, many of whom had come through his church, entrusted with him their life savings. They saw a man whose great humility was outweighed only by his uncanny ability to outfox the markets. PFG had made him a wealthy man, even if the trappings of success—fancy cars, designer clothes, lavish vacations—held no great interest for him. His most expensive purchase was a five-bedroom home in Bradenton, Florida, with a heated pool, just a short walk from Sarasota Bay. He remodeled it with a friend and did the landscaping himself.

But the man who stood over her that early June morning in 2012 had become practically unrecognizable to seventeen-year-old Hannah Price. Once robust and focused, he’d grown distant and distracted. He’d gained weight. He looked haggard. The father who might utter “golly” when he was upset now cussed and fumed. Ashamed, he’d ask his children to pray for him. And they did, even as he sold their home in Florida and moved here to Valdosta, to a house half the size and a third the price. Eighteen months earlier, his firm had taken a controlling stake in Montgomery Bank & Trust, located in tiny Ailey, Georgia, halfway between Savannah and Macon. Hannah didn’t know the details, but she saw enough to conclude it had been the worst mistake of her father’s life. As she drifted between slumber and wakefulness, she figured her father was saying a prayer for her before leaving on another business trip. But why was he weeping?

The ferry from Key West to Fort Myers takes three and a half hours and leaves around six in the evening. By 7:30 in late spring, when the sun starts to set, there’s little to see. Fifteen miles out in the Gulf, you’ll pass the sparkling lights of Marco Island, Naples, and Bonita Springs as the ferry motors by the barrier islands of Estero Bay, home to bald eagles, gopher tortoises, and fiddler crabs. Five tributaries feed the bay, one of which is the Estero River.

On the evening of June 16, 2012, passengers likely paid little attention to the man in the khaki shorts and white shirt. As the ferry drew closer to the Estero, the man walked outside to the deck. The air was heavy with moisture. It felt like rain.

![]()

Estero had been my home when I was in the sixth grade. The Estero River is a tea-colored, brackish-water river that comes off the coast and trickles from the Everglades swamp. The banks of the Estero were lined with giant banyan, various oaks, and many tropical plants and trees. On the north side of the river that backed up to our restaurant was a large orange grove. The south side was just jungle and a state park, which was filled with hiking trails among the sand and oaks. To the immediate south was a small town called Bonita Springs and to the north is Fort Myers.

The river and coastal swamp were absolutely full of wildlife mysteries—mysteries that kept me awake at night. I dreamed of catching a ten-pound redfish or a thirty-pound snook. I wanted to see where the biggest alligator lived and how far the sharks made it up the river from the Gulf of Mexico. I ran as wild and free as a boy could ever dream.

Thirty-five years later, I made my plans to leave this world at one of my favorite places in life. I found a quiet spot on the outside second-floor deck of the ferry that was somewhat out of the wind and rain. I don’t remember anyone being on the deck with me. I just sat quietly, praying what prayers I could put together and wiping tears from my cheeks.

I intentionally [had] packed as though I was really going somewhere so my family would not think it strange that I was leaving for a week with no clothes. In addition, [the bag] was full of large envelopes and lengthy letters I would drop off at the post office before I left Key West. Now, I threw my small carry-on suitcase overboard along with my cell phone. I had nothing left but a backpack with diving weights and my driver’s license.

The mist was turning into a light rain. I moved to the third-floor deck, and I sat on the floor against a life jacket box. When the last light of day was gone, I became engulfed in a sea of great darkness—a darkness that would bring terror to any man’s heart. I immediately wished for my warm bed and that I would wake up and find that this was only a bad dream. But my condition was one of hopelessness and no amount of wishing could get me out. Depression had totally consumed me. It was time to go. I needed to make my way over the rails and off the edge of the boat. I would jump from the third-floor deck and be gone.

—From chapter four of The Inglorious Fugitive

Lee Price gave me a copy of the first eight chapters of The Inglorious Fugitive, his memoir in progress, at our third meeting. Over the course of four visits in February and March at the Bulloch County Jail in Statesboro, we talked for ten hours. The former pastor, financial adviser, and bank director is being held there until his trial on federal charges of bank fraud, related to the failing of Montgomery Bank & Trust in 2012. (Federal prosecutors in New York have also indicted him on wire and securities fraud charges.) When he disappeared on June 16, 2012, he left behind a bank whose collapse was imminent and dozens of investors whose life savings were gone. Lee Price became one of the FBI’s most wanted fugitives, with a $20,000 reward offered for information leading to his capture.

Lee Price gave me a copy of the first eight chapters of The Inglorious Fugitive, his memoir in progress, at our third meeting. Over the course of four visits in February and March at the Bulloch County Jail in Statesboro, we talked for ten hours. The former pastor, financial adviser, and bank director is being held there until his trial on federal charges of bank fraud, related to the failing of Montgomery Bank & Trust in 2012. (Federal prosecutors in New York have also indicted him on wire and securities fraud charges.) When he disappeared on June 16, 2012, he left behind a bank whose collapse was imminent and dozens of investors whose life savings were gone. Lee Price became one of the FBI’s most wanted fugitives, with a $20,000 reward offered for information leading to his capture.

He reappeared last New Year’s Eve on I-95, after a routine traffic stop in Glynn County. This was eighteen months after he led everyone to believe he was on his way to die. Where had he been all that time? When he made his first appearance before a judge on January 2, he looked nothing like the clean-cut man of God he’d been for so much of his adult life. He’d lost weight, let his hair grow long, and sported a beard, dyeing both black. Journalists from New York to Paris wanted to know: Was this a Bernie Madoff of the South? Was he a fall guy? Just who was Aubrey Lee Price?

A few weeks after his arrest, I wrote him a letter. He responded with a phone call and an invitation to have a conversation, the only one he’s had with a journalist since his capture. Price was eager to tell his story. It was, quite literally, incredible. It included, in no particular order, a stint as a bag man for a Latin American cocaine kingpin, a vision quest atop a South American mountain, an almost obsessive devotion to fitness, a dependence on Adderall, and a collection of odd and occasionally endearing criminals and drug addicts with names like Kmart and Pico. His tale was, in many ways, like the script of a Hollywood film. The sort of movie you’d enjoy while shaking your head at its implausibility. In fact, Lee Price thought his adventure might make for a movie, in time. He said screenwriters had been in touch with him since he’d arrived in jail. A book agent had reached out too.

Could his “unbelievable story,” as he himself called it, possibly be true? Or was it a Walter Mitty–esque fantasy spun out of legal necessity and the imaginings of a man in the midst of the worst midlife crisis in history? As Price discussed the bank and his life on the run, fleshing out details from his book, he appeared composed and sincere, laughing and crying as he talked, quoting Scripture, Will Ferrell films, and weed prices alike. Still, I couldn’t help but wonder: When can you trust a man who admits he’s been a fraud? A man who, if authorities are correct, was essentially running a Ponzi scheme even before he got involved with the bank so many thought he’d save?

|

Online exclusive Author Charles Bethea chats with our editor in chief about how he got this story |

In 1976, after a series of business setbacks, a former Marine named Jim Price moved his young family from Atlanta to Florida’s Palm Beach County, where they farmed squash and eggplant. His second son, whom they called Lee, was already a hard worker at ten. “He picked vegetables all day long,” Jim Price told me, “and never complained.”

They lived in Loxahatchee, then Naples, later opening a family restaurant by the Estero River and moving into an apartment above their business. Lee was a quiet, content boy. He was a good athlete at twelve, but small: five feet four, 110 pounds. He and his brother Greg bussed tables, fished, played tennis. It was a simple, bucolic life.

Jim Price still wasn’t satisfied, though. So they moved to Lyons, in southeast Georgia, near his mother. Toombs County was where Lee spent his junior high and high school years. “He was never cocky,” said his eleventh-grade chemistry teacher and tennis coach, Victor Wolfe, who admired Lee enough to name a child after him. “Very coachable. He had a good head on his shoulders. He was sensitive and hard-working.” Lee picked onions each summer until tenth grade, worked at the Handy Andy, won track races, and drove a 1973 red Vega hatchback he bought himself, which sometimes needed a push to start.

![]()

I paid my way through a four-year private college on my own. I was not a trust fund brat, and I did not like kids who got everything handed to them. I still do not. I worked for everything and anything I had. I only took out one small student loan, which I paid back before I even finished college. I personally hated any kind of debt and vowed in my early twenties to never owe anyone anything. Until my late thirties, I never really had any debt other than a mortgage. I never wanted to owe any man anything but the love of my heart, and that is how I lived most of my adult life.

—From chapter two of The Inglorious Fugitive

Beginning in 1987, Lee Price became deeply involved in church. He worked at a power plant for two years, making enough money to attend nearby Brewton-Parker, a Baptist college in Mount Vernon, Georgia, where he met his wife, Rebekah, and graduated in 1990 with a bachelor’s in ministry. During breaks he worked as a youth pastor. At First Baptist Church of Swainsboro, an hour north of Mount Vernon, he mentored Doug Brown, who was then fifteen.

“He liked to joke,” Brown said, “and make funny voices. This was a very evangelical church—people wouldn’t listen to secular music—and he was a deeply religious person. Really likable, though. He played the youth minister part well.”

Price went on to pursue a master’s degree from Columbia International University, before taking his first head minister job in Pelion, South Carolina, where his first two children, Nathan and Hannah, were born. Price was open and friendly with everyone. He helped people who didn’t go to church, who felt lonely or alienated.

As a pastor at Griffin’s Teamon Baptist Church during the late nineties, Price gave at least 10 percent of his modest salary back to the church and built a small house nearby. “He’s the best preacher I’ve ever worked under,” recalled Gail Cantrell, Teamon’s financial secretary at the time. “And he set a great example. My daughter is a missionary because of him.”

Price loved spreading the Gospel. Accompanied by members of his congregation, he took annual mission trips to Venezuela. But money was tight on his pastor’s pittance. Professors at Brewton-Parker had interested him in investing; he began pursuing licenses and studying the markets on his own.

In 2000 Price moved the family to Alpharetta and went to work for the brokerage firm Salomon Smith Barney. This surprised Doug Brown. “The guy was destined to be a preacher,” Brown told me. “Everything about him. He was very dynamic, convincing.” Those same attributes, of course, were useful in the financial world.

Price’s new office was off I-285, near Peachtree Dunwoody Road. Not far away was Clear Springs Baptist Church, where he also served as pastor for six years but directed that his $30,000 salary go toward mission work. “It all went to Global Discipleship, his charity in Venezuela,” said Paris Stone, financial director at Clear Springs and Price’s client for years. “He was very good to them.”

For eight years, Price’s family lived in Alpharetta. His sons became good tennis players; Samuel held a top ranking in the state. Every night, Price lay down in bed with each of his children and said a long prayer. By the end, they were usually asleep.

Lee Price took his work seriously, but when the market closed, his family could count on seeing him. He came to their soccer and football games, their tennis matches, their recitals and plays. He taught Hannah to play the guitar, piano, to sing. He did everything he could to make sure they were happy and big dreamers, Hannah said. That they knew right from wrong.

“He’s my hero,” his son, Nathan, who is studying to become a journalist, told me. “My favorite thing to do was watch my dad preach. I would just blow up with pride.” Lee Price was unusually generous, his family and friends said. Material things weren’t important to him. He loaned money without expecting to be repaid. He gave away a car to a family in need. He drove the same old truck, a 2001 Dodge Durango, for years.

In 2003 he left Smith Barney for Banc of America Securities; he’d have more clients and a better salary. His investor list soon ballooned to 500 and he worked constantly, became less involved with his church. He started PFG in January of 2008, a little over a year after obtaining his Series 24 broker license. He eventually had more than 100 clients. He moved the family to the 5,500-square-foot home in Bradenton, Florida, near some of his best memories as a child.

Clint Davis, a former Teamon deacon, visited. Price was the same man he’d come to admire more than a decade earlier, when they’d begun taking mission trips together: “A solid husband and father, one of the most giving men.” In 2011, when Davis’s wife was dying of cancer, Price wrote her a letter and read it to her at her bedside. “That’s the kind of man he is,” Davis said.

Ailey is a leafy hamlet in south-central Georgia with barely 500 people. The town’s claim to fame: Sugar Ray Robinson was born there. In 1926 the Petersons, a prominent local family, founded a bank in Ailey: Montgomery Bank & Trust. Through the generations, the Peterson family has produced congressmen and state senators, friends of Governor Eugene Talmadge and in-laws of Governor Richard Russell. Indeed, the town was originally named Peterson. “They have their own cosmos,” said William Ledford, editor of Vidalia’s the Advance.

Miller Peterson Robinson, known as Pete, is seen as the most powerful living member of the Peterson clan. Best Lawyers magazine recently named him the “Government Relations Atlanta Lawyer” of the year. Robinson came to know Nathan Deal when the two men were in the state senate in the early nineties, and he was on Deal’s four-man transition team after the governor’s election in 2011. Now chairman of Troutman Sanders Strategies lobbying group—recently named the top governmental affairs firm in Georgia—Robinson was elected chairman of MB&T in May 2009. His uncle, Thomas Peterson, was president (earning more than $500,000 in each of the two previous years); another uncle, William (Thomas’s brother), and a cousin, Mary Jeanne Fulmer (Thomas’s daughter), sat on the board of directors.

MB&T would never be a “big” bank, in any conventional terms, but when the economy heated up in the mid-2000s, it began looking beyond its small-town confines toward the coast, where developers were building waterfront homes. In 2006 it opened a branch on St. Simons Island.

Then came the Great Recession. By December of 2009, 66 percent of Georgia banks were unprofitable, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Twenty-five banks failed that year, twenty-one the next. In May of 2010, Thomas Dujenski took over as the Southeast regional director of the FDIC, based in Atlanta. At the time, Georgia had more bank closures than any other state. Dujenski deployed 564 staff to examine and resolve troubled banks, up from 364 in 2007. About 100 of them were tasked with scrutinizing Georgia banks.

Asked why Georgia led the nation in failed banks, Dujenski, who retired in May, cited loosened underwriting standards and a great deal of speculative lending in commercial real estate.

MB&T was a prime example. Its expansion to the coast couldn’t have been timed worse. As of December 31, 2009, a year before Price and his firm took a controlling interest in the bank, nearly two-thirds of MB&T’s nonperforming assets were clustered in Glynn and Camden counties. The bank closed its branches there. “Developers are defaulting on their loans with us,” bank officials said in the offering memorandum sent out to potential investors. Indeed, the percentage of “adversely graded loans”—those at varying levels of risk of being defaulted on—went from 15 percent in December 2008 to 28 percent just nine months later, according to a 2010 review of a sampling of the bank’s loans by Steve H. Powell & Company, a Statesboro firm that examined the bank. In October 2009 the FDIC stepped in and requested that the bank get its balance sheet in line, but to little avail; by July 2010 a full 36 percent of the bank’s loans were considered to be adverse, according to Powell’s report.

The report had harsh words for the way the bank was being run. Among its conclusions: “Real estate appraisal quality was found wanting”; “the bank has experienced a drastic decline in asset quality”; “underwriting and documentation should be improved.” Characterizing it as a “serious infraction of bank policy,” Powell pointed out that a bank official, with no authorization from higher-ups, had advanced a cashier’s check to one of the bank’s “large borrowers” to the tune of $64,450. The advance was not affiliated with a new loan or tied to an existing line of credit. The check was not accompanied by a “legal obligation to repay,” the report said.

Powell’s conclusion? MB&T will “experience further deterioration” as the market lags.

Why then, one wonders, would anyone invest in such a bank?

![]()

The bank deal was introduced to me the summer of 2010, and I have to admit, it sounded very intriguing. I had no community banking background or experience, but several of my clients and other contacts were convinced that these community banks needing capital were opportunities we should consider. After attending a number of dog and pony show meetings with a couple of different banks in the state of Georgia, my interest perked up. I listened to the stories of how, if certain amounts of capital were injected into these banks, they would be gold mines again.

—From chapter two of The Inglorious Fugitive

Federal prosecutors have another explanation for Price’s sudden interest in banking: He’d been losing his investors’ money at PFG. Despite the fund’s mission of “positive total returns with low volatility,” he’d been investing his clients’ savings in high-risk investments and real estate deals in South America. He bet big and, if the feds are correct, lost big. To cover his tracks, he sent his clients account statements that showed, according to authorities, “fictitious assets and investment returns.”

On December 31, 2010, the majority of the bank’s common stock shares were sold to PFGBI, a subsidiary of PFG created expressly for the bank deal, for approximately $10 million, effectively putting Price’s firm in control of the bank. The investment was bolstered by an additional $4 million, largely from locals who saw Price and his team as saviors. Price took charge of investing the bank’s new $14 million capital injection, which he had largely supplied; that was, after all, his expertise.

Among the investors was Dan McSwain, who made his fortune as the founder of McCar Homes, once one of the nation’s largest homebuilders. McSwain had grown up in the area and was also a client of Price’s investment firm. He invested $1.5 million into the bank. “I’m sold on this area,” he told Southeast Georgia Today in January 2011, just after the investor group led by Price took over the bank. “I like the bank, the people here, and the response of the people who were willing to put money in the bank. It was because of that we were willing to make this investment here.”

McSwain’s son, Keith, himself a homebuilder and owner of KM Homes in Alpharetta, invested $500,000. But he wasn’t so sanguine. “I did not want to do the deal,” Keith McSwain would say in a deposition in November 2012. “My father said, ‘I really want to do this for the hometown’ . . . And out of respect to him, I said, ‘I don’t want to do it, but if that’s what you want to do, then I’ll do it.’”

Keith McSwain’s concerns were validated almost immediately. In his deposition, he recalled being invited to sit in on a board meeting not long after Price and his firm took control. The balance sheet worried him, he said. Later, at dinner, he cornered Price. “Lee, this is a major problem,” McSwain said. After that, McSwain said in his deposition, he was not invited back.

“In July 2011 I got a call from my father, and he said, ‘Hey, I just got a call from Lee, and they had an audit and a write-down, and basically all the equity in the bank has been severely reduced.’”

Charles Clements, an MB&T executive vice president who was let go the day before Price came aboard, told me: “We screwed up on St. Simons. That was the downfall. It was like a tsunami hit us. But there were a lot of terrible loans made. A lot. We were financing new cars—banks don’t finance cars no more.”![]()

So, now we buy the bank, and we find out that these numbers are nowhere near correct. How bad are they off? Instead of a $3.4 million hole, we’re in at least a $50 million hole. That much in total possible losses. The management claimed the smaller number was accurate and correct. It’s written in a statement. The FDIC and state banking authorities have seen this and done reviews of the bank. What are we supposed to do? We believe them. These guys know the bank. They’re trained to understand its condition. It’s not my expertise. I’m believing what they say. We wouldn’t have put the money in if we didn’t believe them.

Steve Powell is a key name. I’m wet behind the ears on this thing. I didn’t even know there was an independent loan review group coming in to do that, and that their file should have been given to us during our due diligence period. They’re gonna say, “You never asked for it.” But don’t you have the ethical and moral obligation to tell us the opinion of the loan review guy? You’re taking money from local investors who live and bank in that community, asking them to put money in.

—From my interview with Price, February 15, 2014

Through his attorney, Pete Robinson declined comment for this story. But among the deluge of lawsuits filed in the wake of Price’s disappearance and subsequent arrest, one in which Robinson is a codefendant, along with the bank’s former president and CEO and former CFO, offers insight into how even something presumably as clear-cut as a bank’s assets can be open for debate.

MB&T had its offices

After Price’s disappearance, Melanie Damian, the court-appointed receiver charged with recovering as much money as possible for Price’s investors, sued Robinson and other former MB&T officials for more than $10 million, claiming the bank hid from Price the bank’s true condition. For one thing, the lawsuit alleges, bank officials never revealed to Price before the sale the existence of the Powell report. For another, the suit claims, the bank drastically underestimated the amount of money it needed to set aside to cover loans it expected to go bad. If that amount had been reported accurately, Damian argues, “it would have been not only ill-advised to invest in [MB&T], it would have been unthinkable.”

After the sale, according to the suit, Price finally spoke to Powell, who told him that Price would have been “better off investing his clients’ funds in a lottery ticket, because if he had done that there would have been at least some chance of a return.” (Powell did not comment for this story.)

Attorneys for Robinson and other former bank officials paint a different picture. Damian fails to take into account the $17.6 million in loans the bank wrote off, the defendants argue. What’s more, in what appears to be the banking equivalent of “caveat emptor,” Robinson’s attorneys argue that if Price relied solely on the bank’s representations of the money it would need to cover bad loans, that “reliance was misplaced.” As for the Powell report? Although they don’t claim Price saw the report before the sale, the former bank officials play down its importance: “The Powell reports merely reported on a sampling of the bank’s adversely classified loans.”

In any case, it’s Price’s contention that his growing awareness of the bank’s dire condition influenced what happened next. According to U.S. prosecutors, Price indicated to the bank’s directors and investors that MB&T’s capital would be invested in U.S. Treasury securities. But between January 2011 and June 2012, he allegedly misappropriated, embezzled, and lost more than $21 million in speculative trading. Additionally, according to the indictment, he fabricated statements to show that the bank’s money was safe.

Price himself admits as much:

With losses mounting daily in my investors’ accounts, I did the unthinkable. I deceitfully devised a plan to use the bank’s securities account, and began trading those funds with hopes of making bigger returns to build the bank’s capital account back up and pay investors back. It was the worst decision of my entire life, and I take responsibility for it. There is no one else to blame for this except me. In doing so, I had hoped the bank could make enough money to survive and maybe wait out the horrible real estate values that saddled the bank’s many bad loans. With time running out and facing extreme pressure, the losses in all trading accounts compounded daily. The [situation at the] bank had forced me into quick, high-risk-taking that caused me to make many very hasty and irreversible decisions. No matter how hard I worked or tried, I could not come up with any money-making ideas or trades.

—From chapter two of The Inglorious Fugitive

As 2011 wound down, Lee Price was “just wrecked—physically, mentally, and emotionally,” his father said. By early 2012, Lee Price began to liquidate his possessions. He sold the family home in Bradenton for $27,500 less than he’d paid for it four years earlier. He set up an office in Lyons, at his parents’ old home, to be closer to the bank. The house was basically empty, save for a big desk. He put a bed next to it and lived there, making hundreds of calls and emails a day, sleeping little. He started smoking Camels again, and losing his temper.

“My health problems have compounded greatly,” Price later wrote in a twenty-two-page letter to regulators, “to the point of agonizing headaches and stomach ulcers beyond belief. I am sure that I suffer from SAR (specific absorption rate from too much cell phone usage). I literally spent hours on the phone every day with clients, bank-related calls trying to solve problems and allay concerns. My head was on fire much of the time. I broke several phones in anger. Various cancers surely have taken me over.”

Since its inception, PFG had raised $40 million from investors, $36.9 million of which went into a trading account at Goldman Sachs. When the account was closed in mid-May of 2012, only $480,000 was left. At home, Price stocked up on supplies for his family: toilet paper, water, canned food. He took his children to play golf and to Wild Adventures theme park. He taught his youngest, Esther, to drive.

“We could tell he was under pressure,” said Hannah. “He’d say, ‘Keep me and my business in your prayers. Be strong and keep your eyes on the Lord.’ He eventually told us we’d probably be going into bankruptcy.” According to prosecutors, airline records show that Price went to Venezuela in early June. Whenever he was away, his children sent him texts and emails full of Scripture, love, and encouragement. A typical one from Hannah: Be strong and keep believing, Daddy. We love you.

The night before he left for good, he watched Braveheart with his oldest son. They stayed up late, Nathan recalled, talking about “church, the ministry, where I was heading in life.” His last words to Nathan, in person, came the next morning. Price had tears in his eyes: “Never give up. Never give up.”

He caught a plane. Security cameras show Price wearing khaki shorts, sneakers, a white long-sleeve shirt, and a red cap while exiting the Key West airport terminal that day. Next he’s seen getting in a taxi, and then—after changing into a white hat and visiting a post office and a dive shop—boarding a ferry from Key West to Fort Myers. His black backpack appears full and his cap is pulled low over his face. A few hours later, he stood at the railing.

He did not jump.

![]()

His children knew something was wrong when they got no response to their Father’s Day emails; he always replied. By Monday, the letters he’d posted from Key West had arrived at their destinations. In the letter to regulators, he was despondent and penitent.

![]()

I am 100 percent responsible for the losses I created. I blame no one but myself. Relating to PFG, I falsified statements with false returns. I created false financial statements and defrauded investors, regulators, other work associates, and bank employees. I lost money through trading and various investments, including the Montgomery Bank & Trust securities portfolio. I hid many things fraudulently and deceptively, to try and give myself more time to pull some positive returns together . . . No one else had any knowledge of any fraudulent activity. I estimate it is about $20 million to $23 million in losses, excluding the Montgomery Bank & Trust commingled Goldman Sachs securities account (about $15 million).

—From Price’s “Confidential Confession for Regulators,” mailed before his disappearance

“No one knew what to think,” Hannah Price said. The Prices notified the Coast Guard, but a storm made the search difficult. “We were left hanging,” Jim Price said.

Lee Price’s wife and four children had less than $5,000 in cash. Rebekah was too upset to eat. Seventeen-year-old Hannah felt physically ill. “I walked around the house, just crying,” she said. “He was my best friend.” She took time off from her job as a waitress. On his desk she’d placed a photo of the two of them on a mission trip. On the back she’d written, “I don’t know what I’d do without you.” What good was it now? She requested extra shifts.

Four months later, Rebekah filed papers to have her husband declared deceased. “We didn’t have a body,” said Hannah. “No evidence he was alive or dead. We all just decided to believe what he’d written and go on about our lives as if he was dead.”

|

Online exclusive Read the full text of Price’s “Confidential Confession for Regulators” |

Not everyone agreed. A coworker looked Hannah in the eye and said, “Your daddy’s alive.” The FBI thought so too, eventually releasing a statement: “Price lied to investors about where their money would be invested, and lied to them about the solvency of his company. He lied to the bank on whose board he served about investment of bank capital, and lied again to cover up that lie. It is therefore reasonable to assume that Price’s talk of suicide was also a lie. The FBI is actively looking for Aubrey Lee Price.”

Where was he? In his apologia, Price said, “I leave this world in shame.” His family read that to mean he would kill himself. Instead, within days of disembarking the ferry, he told me, he’d made his way to a Latin American country—he wouldn’t say which—where he entered the orbit of a friend of a friend, a casual acquaintance he’d come to know over the past seven years. In his book, Price refers to the man as “Pedro,” whose family business included cell phones, farming equipment, and hotels. One day, Price writes, the two men dined at one of Pedro’s restaurants.![]()

After drinking a glass of liquor, Pedro leaned forward, cleared his throat, looked me dead in the eyes, and said, “Listen to me very closely. Before we talk any further, you need to know one thing. I know where your children are right now and I can have them all dead in just a few hours with one simple phone call.”

I held my stare as my hands began to shake and sweat intensely. I felt something run through my veins. It was not fear. It was the deepest hatred I had ever felt . . . I slowly reached into my pants under the table. I pulled out a loaded .38 Magnum [Editor’s note: There’s no such weapon as a .38 Magnum] and pointed it straight above his belly. He heard me cock the trigger. I said, “Listen to me very carefully. Do not take your eyes off of my eyes. Do not even blink at your bodyguards. We will both die right here, right now, and I am more than ready to go.”

I looked at him with fire in my eyes and said, “Por que chingar le diria algo como eso?” Which means, “Why the f— would you say something like that?” He started laughing. He said, “I wanted to see if you are alive, if you have feeling left in you. I see that you do!” As firmly as I could, I said, “I may be a mere shell of a man at this moment, but I do not care who you are. I have absolutely no fear of death. I will put at least six bullets in you before your bodyguards empty every shell of their guns into my body if I even get a small whiff that you are thinking about touching my family in any kind of harmful way.” He said, “Tranquillo, tranquillo. I promise that nothing will happen to your family as long as we have an understanding.”

In seven years of meetings with this man, I never dreamed he would speak to me that way. I did not have much choice but to follow him. I could feel my face turning pale and my body shaking, so I hurried to the bathroom and vomited my entire meal. Tears were streaming down my face again, and I sat bent over, trying to catch my breath. After a few minutes, I finally regained my composure enough to walk out. [Pedro] smiled and asked if I shit in my pants. He put his arm around me and said, “I think you and I can work together just fine.”

—From chapter five of The Inglorious Fugitive

In August of 2012, less than two months after Price’s disappearance, a federal judge in Atlanta appointed Melanie Damian as the receiver. Compared with the $21 million in losses Price allegedly incurred, the pickings were slim: They included $345,653 from a Bank of America account, $10,073.14 from a TD Ameritrade account, and $5,230.25 from the sale of silver dollars and half dollars.

Damian visited properties purchased with PFG investor money, traveling even to Venezuela, where Price was the listed owner of two working farms that grew corn and sugar cane, and held a stake in a third. Damian sold off various parcels throughout Georgia and Florida—a handful of condo units in Florida, primarily. Not all the sales netted as much as expected. The market value of a seventy-one-acre plot of timber and hunting land in Lyons, straddling the Toombs and Emmanuel county lines, was initially put at $695,000 by Damian’s real estate agent. But when it finally sold this past January, it fetched $72,080—barely more than $1,000 an acre.

On December 31, 2012, a judge in Florida declared Aubrey Lee Price dead. Less than a month later, one life insurance provider issued a check for $1.25 million, which eventually went into the receiver’s growing asset pool. By October 2013, Damian had collected $1.8 million from various policies. Within a few months, though, all the companies would request their money back. After all, Lee Price wasn’t dead.

![]()

We walked through a back hallway and through a side door where we entered his club. The room was full of flawless, young, beautiful, barely dressed ladies dancing for hundreds of men to loud, thumping Latin music. There must have been ten on the stages and another thirty sitting with men. When Pedro walked in, everyone looked as if the king were coming through. I followed. We went out another door and down a long hallway. We must have passed six different well-armed guards, and then someone opened the doors to a large warehouse room.

There’s thirty to forty workers; they’re stuffing little bags full of white powder. [Pedro] took me to every station. I spent a couple of hours just listening. I’m a curious person by nature. I’m adventurous. I have very little fear. We walked outside and stood on the loading dock, looking over a lake and this incredible city. He stood there and he said: “Do you want to be on the receiving end of a stream of piss? Or the giving end of the stream of piss?” I told him I’d never thought about it like that.

Pedro laughed and walked upstairs to his plush office, where he continued his pitch: “I want you to work for me. I can give you whatever you want. If you can help me, I can help you make millions.”

He said, “You are a criminal, and we are all criminals. I need someone like you that can help me, and I want to help you. I have many problems throughout my businesses. I will pay you very well. Yes, there are risks, but you will learn quickly and I personally will train you. My family has millions and millions of dollars in U.S., European, and Asian banks. You know banks. You know investments. You will know our biggest and best buyers of our product in the United States.”

—From chapter five of The Inglorious Fugitive and from my interview with Price on February 22, 2014

On July 31, 2013, Melanie Damian was deposed by an attorney for KM Homes, whom she had sued, seeking recovery of PFG money she claimed had been loaned to KM Homes. From the transcript:

Q. When do you think the fraud actually began?

A. Well, certainly by 2009 [Price] was misrepresenting the returns.

Q. That’s a critical part of this fraud, is that correct?

A. Right.

Q. And in a Ponzi scheme, when he is representing those returns and people are requesting payouts on those returns, he’s basically taking money from one investor and giving it to another?

A. Correct.

![]()

I was an expert taster of cocaine. Understanding the quality. I had to taste it to know if it was any good or not. Quality control. Every one of my friends were criminals. I didn’t have any friends that were normal people. On purpose—I didn’t want to be around anyone normal.

I’d never been around people who used drugs before. I’d preached against alcohol. But now I’m sitting around with a Bud Light in my hand, faking drinking it. I’d usually drink about half a bottle at most. That was hard for me; I just don’t like it. But it was part of my cover.

—From my interview with Price on March 1

Damian’s lawsuit against KM Homes centered on an arrangement struck sometime in 2010 between Lee Price and Keith McSwain. According to McSwain’s deposition, his business needed an injection of capital, so he called Price looking to make a withdrawal from McSwain’s PFG account. Price, McSwain said, had another idea. “How about we do it this way?” he said to McSwain. So over the course of seven months beginning in August 2010, Price transferred almost $4 million from PFG to KM Homes. In turn, starting in October 2010 and continuing up until just before Price’s disappearance, KM Homes paid back $1.9 million, with a little more than $671,000 of that considered a “return.” If that sounds like a loan, it did to Damian as well, who made it the basis of her lawsuit against KM Homes. After all, KM Homes agreed to pay back the amount at an interest rate that ultimately reached 17 percent. McSwain and his attorney argued that the money in question was McSwain’s to begin with, and represented his investment in PFG. On July 31, 2013, McSwain was deposed and questioned by Guy Giberson, an attorney for Damian:

Q. Okay, Mr. McSwain, is it your contention that the money that is at issue with respect to this case, that none of it was a loan?

A. It is my contention that it was my money, my equity of which I got and put in KM Homes to grow the business.

Q. Then why did KM Homes pay interest?

A. Because that’s the way Lee wanted to set it up. And then we paid him a return, as he was saying he was paying us a greater return.

Q. Why pay him a return if it wasn’t a loan?

A. Because it—say that again?

Q. If it was not a loan, why pay any interest at all?

A. Because not to hurt the fund.

Q. So it was a gift.

A. I didn’t say it was a gift. That’s your word. I looked at it as trying to not hurt the fund.

The suit went to trial on April 21. Damian sought $3,273,000 plus $503,055.30 in accrued interest through April 30, 2013, plus $1,524.41 per day after. On April 23, as the jury was set to resume deliberations, the two parties reached a settlement. According to Damian, KM Homes agreed to pay $1,665,000 to the receivership. Through his attorney, Keith McSwain declined to comment.

![]()

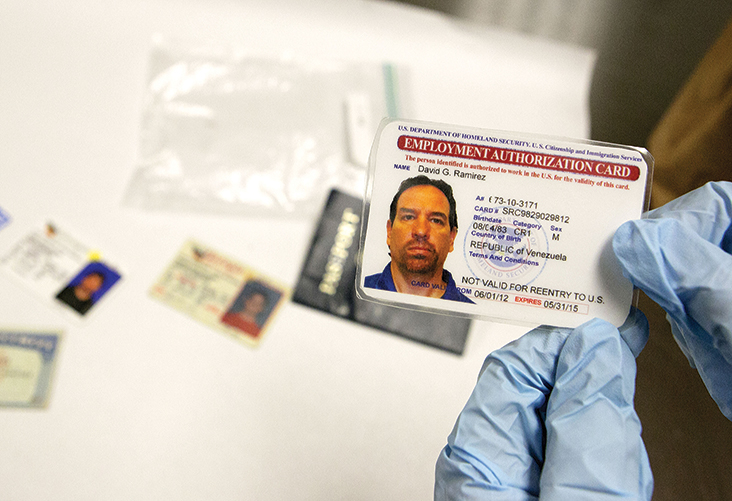

I made my way back to the States and began working on plan B away from Pedro. North Florida was where I ended up for a couple of reasons. One is that it was familiar territory, and two, it’s where Pedro had operations. If I needed him, I could get to him quickly. I lived out of a budget hotel for a week or so and made a couple fake IDs. Once I was able to purchase a bicycle, I road that bike all over the place, mainly for exercise and the working off of stress.

I had few friends and quite a few associates. My rules were kind of simple: Trust absolutely no one. Talk as little as possible and do as little evil as possible. Get close to no one. The focus for the first six months was to restore my spirit and soul and to try and rebuild some mental capital. It was very difficult. The beast within had me, and I could not break free.

I understand every strain of marijuana. I spent time in twenty grow houses there. I know where there are twenty grow houses in the Southeast right now. I was just walking through whatever doors opened for me. I met all kinds of people. People that I love now. They don’t judge you. And I liked that. I’m a criminal, we’re all criminals. We’ve got each other’s backs. There was a level of comfort there, and I was lonely. I went to bed every night crying, quoting Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want; he makes me lie down in green pastures . . .” I didn’t stop crying before bed until probably a few weeks ago.

I constructed Jason [as an alias]: a divorced guy who lost all his money and his family because of cocaine addiction. Now I’m trying to recover and I’m reading the Bible to figure out where I’m going. And I’m depressed. Because I was. All of my aliases had a lot of truth to them.

My other names were the initial J, Gator, and Diesel. Gator was the funniest because [I wore] Florida Gator football apparel, including a hat, acting like I was a Gator fan. My roommate in college was a Florida Gator fan, and it made me want to vomit. I have always been a UGA fan, so I believe I helped the Dawgs win the last few years by being a curse to the Gators.

—From chapter one of The Inglorious Fugitive and from my interview with Price on March 1, 2014

According to a Marion County, Florida, police report filed in early January, just after his capture, Lee Price lived for a time in Citra, Florida, on Jacksonville Road, and allegedly tended to 225 marijuana plants growing inside a mobile home. This was on the property of a couple named Bonnie and Richard Sipe, who knew Price only as “Jason.” They let him live rent-free in the old trailer in return for doing some gardening and yard work.

The Sipes wouldn’t talk to me, but they did tell a reporter from the UK Daily Mail, “We thought alcohol destroyed his life. We thought he was from South Carolina and had an ex-wife and a couple of kids.”

arrest on December 31 of last year

In late March, I traveled to tiny Citra, home of the pineapple orange, population around 7,000. I stood outside gas stations, grocery stores, auto body shops, and the abandoned property, overgrown with weeds, where Price lived. Pointing to before and after pictures of him on my phone, I asked a hundred people if they knew this man who went by Jason or Lee. A few said he performed odd jobs around town—repairing fences, growing fruit, electrical work—and was occasionally seen with an attractive younger woman.

Mark Abney, a local mechanic and acquaintance, said Price told him he’d been in jail for cocaine use, and his family had kicked him out. After that, he’d become addicted to Adderall. Abney said Price told others that he was a recovering drunk. He knew that Price kept pit bulls—I saw an animal control sign posted on a fence—and was studying Spanish. Once, Price told Abney, he had a close call with police while driving back from Jacksonville with some marijuana in his car. He’d told me the same story.

“He planted palm trees around here,” Abney said, “but I figured he was making his money some other way.”

Price told a local handyman named John Dewese that a sick uncle lived inside the shed on the Sipes’ property where the 225 marijuana plants were eventually found. He said this uncle would shoot anyone who came near him. So no one did. “He was pretty quiet,” Dewese told me. “Kept to himself, mostly. I cut some land back there for him to grow some plants. I guess he was here for a year. Maybe two years, off and on. He said he came from some place called Green Cove Springs. Never heard of it myself.”

![]()

I didn’t have an Adderall that morning. I was driving to Hinesville, Georgia, on I-95, to get my car registered so I could sell it. It was about 10 a.m. I was praying through my prayer list. I couldn’t ever finish. I’d get distracted. It was one of those moments where I was angry at God. I’d just crossed over into the Brunswick area and immediately I thought about the bank. I kept asking, Where are you, God? Why don’t you ever answer my prayers? Why have you left me in this situation? It was the Christmas holidays and I wanted to see the kids. I banged my steering wheel in anger and I remember saying, “Lord, where are you?” I said that like ten times. And then I looked up and there were blue lights behind me. I said, “Thanks, Lord. That’s where you are.”

—From my interview with Price on March 2, 2014

On December 31, 2013, Glynn County sheriff’s deputy Justin Juliano initiated a traffic stop at mile marker 43 on I-95, according to his police report. “The stop was on a 2001 Dodge Ram truck for a violation of the Georgia window tint law, a cracked windshield, and an expired license plate. The driver, who was later identified as Mr. Aubrey Lee Price, was issued a written warning for the above noted violations. I asked for consent to search his vehicle and his person and Mr. Price granted consent verbally. During this search I located a fake Georgia license. The roadside investigation led to the arrest of Mr. Price for giving a false name and date of birth. Once we arrived at the jail, Mr. Price disclosed his true identity.” The cop later told a TV reporter, “It was like a weight lifted off his shoulders.”

In custody, Price called his father: “Dad, I’m alive. I need you to listen carefully. Call this number for me and give them this code: 666.” The code, Price told me, was for Pedro’s people. “It meant run for your life, get rid of your phones.”

“I didn’t know what he was talking about,” Jim Price said. “I couldn’t do it.”

When I first saw Lee Price, outside an interview room at Statesboro’s Bulloch County Jail, he was shorter than I’d expected. His hair had been cut. He wore baggy jail pinstripes, cheap purple eyeglasses left for him by his lawyer, black Crocs, and leg shackles. He shook my hand. “The food is terrible in here,” he said as we sat down. “I mostly just eat peanut butter from the commissary.” He looked his age, forty-seven. But when he smiled—which was often on some days, and never on others—there was something boyish, mischievous about him.

When Price arrived, federal agents warned jail officials to watch for suicidal tendencies. So he was placed in solitary confinement for a few weeks. There, he said, he wrapped himself in toilet paper for warmth and asked for a Bible. On the eleventh day, one arrived. Since leaving solitary he’d spent time in a communal cellblock where, he said, he ministered to fellow inmates and wrote his life story on a computer donated by a friend. On our third visit, he shared eight chapters of the manuscript with me and invited me to quote from it. He also asked me to show it to his father, who called me a few days later and said, “I don’t know how much is fiction and how much is real. It sure would make a good movie, though.”

![]()

Here are some things that helped me survive and overcome depression:

1. Heavy amounts of Bible Reading and Scriptural Meditation (sometimes forty to fifty chapters a day); Continual Prayer; Confession and Cleansing of Sins; Times of Fasting; Personal Worship; Constantly Calling Upon Jesus for help and expressing my faith in Him.

2. Talking truth to myself. I had to keep reminding myself that God does love me. He does forgive me. He has not left me alone. He has not abandoned me. He is present with me. He is working all things together for my good and His glory.

3. Bike Riding, Weight Lifting, Punching Bags, Push-Ups, Jump Ropes, Long walks and Hiking, and a new water- and protein-focused diet.

4. Journaling, Writing, and Reading.

5. A task: New criminal-oriented friends for me to learn and understand. Helping others every chance I could. Adventure, Curiosity, and New Experiences. Willingness to take risk and do whatever was necessary to break free.

6. Working outside in the Sunshine as much as possible. Planting trees and plants.

7. Adderall. 30 milligrams once every 2 days.

8. Levity in adversity. Joy in my trials.

—From chapter seven of The Inglorious Fugitive

In a letter to her father in jail, Hannah Price, who’s now studying radiology at a small Georgia college, wrote: “Lately I have been thinking about how the story of Job is kind of similar to yours and how even though you have gone through a lot and lost some of the things you most treasured, you still are praising God through it. I want to remind you that at the end of the story Job was returned not just what he had in the beginning, but more.”

![]()

Believe it or not, I’m actually having fun here, even though I’m sleeping on the concrete floor. It’s like revival. There’s twenty guys on my block. Every night they come in my room for an hour to sing and hear me lead them in prayer and a Bible story. Our favorite song is “Pass Me Not, Oh Gentle Savior.”

—From my interview with Price on February 22, 2014

“He should have killed himself,” said Wendy Cross, a food truck owner in Decatur who invested her life savings with PFG and lost all $364,000. “But I don’t think he ever was going to do that.

“Being fifty years old with no savings is a scary place to be. But I was one of the youngest who got screwed. I went to a meeting for his investors last year, and I’ll never forget this old lady who stood up after it had all been explained. And she said, ‘But what about my monthly check?’ She meant her annuity, I guess. And someone kept explaining that she wouldn’t get any more of those. And she just couldn’t understand why.”

Mike Gunter, a friend of Price’s who retired from Lockheed Martin, lost close to a million dollars. Gunter wrote Price after his capture: “Early on in this ordeal, I went through many emotions: fear, denial, some anger, sadness, betrayal. But through much prayer, God saw me through it. As strange as it may seem, I’m a better man for having endured this. It has actually been a powerful witnessing tool for me. It’s been a very painful experience for my family, but this big, powerful God we serve has seen us through it all. I hold no ill will towards you. But as you might imagine, I have many questions that only you can answer.”

On my final visit with Price, in March, the thought of growing old behind bars—a single count of bank fraud can bring thirty years—seemed to have set in. That he’d finally been allowed outside for fifteen minutes a few days before my visit, for the first time in two months, only clarified the captivity in which he will likely live for a very long time. “I’d forgotten what the sun felt like,” he said.

When he can’t sleep, he told me, he reads the list of investors’ names written in the margins of his Bible. He prays for them. He prays for Pete Robinson and the bank’s other former directors too.

Price has told his wife not to waste gas money driving three hours to visit him in jail. “They think I’m gonna be home soon,” Price said of his family. “But I’m not. I have to tell my wife to divorce me and find a man who can help support them.” He blinked back tears. “I’m not filing bankruptcy, though. I’m gonna work with my creditors. The day of restitution, that’s the day I’m dreaming of. I don’t want anyone forgiving me until I pay them back.”

So he’s working on his book and talking to the literary agent and the scriptwriters. Maybe his incredible story will make money for those he’s wronged. He said he’s received interest from financial firms, too, in jail. If he becomes a convicted felon, he won’t be able to work as an adviser again. But he could be a research analyst, if a judge allowed it. “There are people at hedge funds who’ll give me a chance. I’d work 24/7 for them in here.”

It’s likely the criminal case against Price will be resolved long before the civil suits surrounding the bank and PFG. In addition to suing KM Homes and former directors at MB&T, Damian, as the receiver, has gone after the FDIC (“the FDIC should have required the bank to shut down in 2009 . . . instead, the FDIC made things worse”), those PFG investors who profited from their investments (yes, there were some), and even the law firm associated with the sale of the bank’s shares. Along the way, her firm’s fees, combined with what’s been paid to forensic accountants, stenographers, and the like, now total more than $1 million.

During one discussion, Price dreamed aloud of leaving prison decades from now: “If I have ten years left, when I’m eighty, maybe I’ll retire down by the Gulf of Mexico. Take my prison earnings and go. Get me a trailer somewhere. That’s where life will end for me, if I’m lucky.”

But he doesn’t feel lucky. The last thing he said to me in person was this: “I’m losing the energy to even fight. Send me wherever I’m gonna go and leave me alone.” He paused, then finally answered a question I’d asked him earlier. “What have I learned from all this? Trust no one.”

Weeks later, when we spoke again on the phone, he was back to his old self, almost chipper. He said he wasn’t giving up. He said he’d reinvent himself in jail. He said crazier things have happened.

With additional reporting by Steve Fennessy

Additional photo credits: opening illustration: mugshot: AP Images; bank: courtesy of Marion County Police Department; Price: courtesy of Clint Davis; bank (standalone photo): courtesy of Marion Police Department; IDs: Landov; Citra house: Alan Youngblood

More: Read our June editor’s note about this story