This article originally appeared in our February 1997 issue.

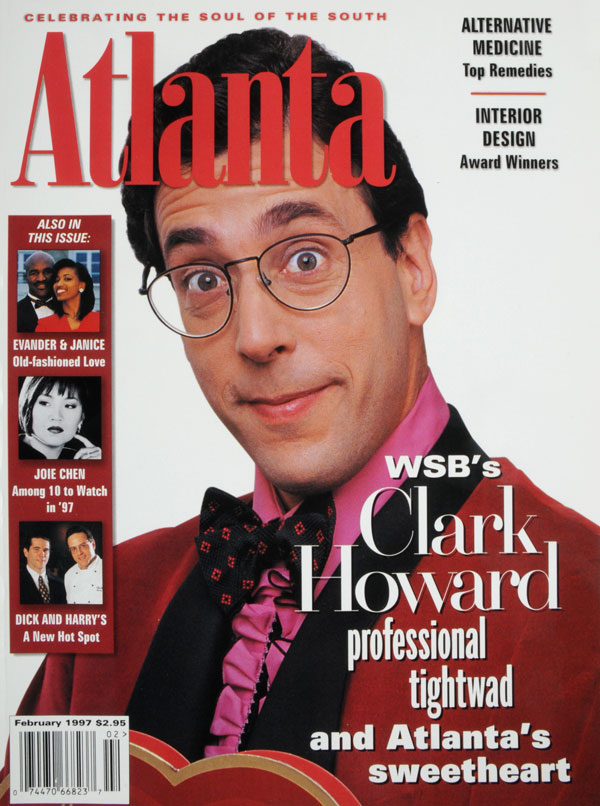

Atlanta’s millionaire consumer guru Clark Howard never aimed to be a media star, much less the darling of the public and the object of beautiful women’s attentions. The bespectacled Howard is a self-described nerd, a dweeb, or as he expresses it, “a complete flake,” whose idea of a fun Saturday night is sitting at the computer searching for best buys.

His notion of a thrilling dinner is a Burger King Value Meal (a double cheeseburger, medium fries and a medium diet Coke for $3.17 including tax), which he’s perfectly content to eat twice a day until, finally, his wife puts her foot down. Or he’ll go for Shoney’s burger and salad combo, which gives a buyer a salad for just $1.49 versus ordering it separately for $3.99. “I mean, it kills me to spend too much,” he says. “Just kills me.”

His notion of a thrilling dinner is a Burger King Value Meal (a double cheeseburger, medium fries and a medium diet Coke for $3.17 including tax), which he’s perfectly content to eat twice a day until, finally, his wife puts her foot down. Or he’ll go for Shoney’s burger and salad combo, which gives a buyer a salad for just $1.49 versus ordering it separately for $3.99. “I mean, it kills me to spend too much,” he says. “Just kills me.”

His legend consists not of nightclub escapades, like so many celebrities, but of tales of exceptional frugality: How he’ll drive 10 miles out of his way just to save a penny a gallon on gasoline. How he works out at a fitness center at Piedmont Hospital because if he ever has a heart attack, he jokes, he won’t have to pay for an ambulance to take him to the emergency room. How he’s furnished his elegant Buckhead home with damaged and repossessed furniture. How his favorite place to shop is Sam’s Club, and he can’t fathom his wife’s fondness for malls.

Yet Atlanta’s consumer guru is far from scorned for his tightwad ways. He’s made himself a millionaire and a cult figure, a local celebrity besieged by fans when he ventures into a restaurant, recognized by radio listeners while honeymooning in Hawaii. Teens love him, travel agents quake at his pronouncements and beautiful women fawn over him.

His face is everywhere, in every important media outlet, as familiar as Ted Turner’s, as trusted as Monica Kaufman’s, as he admonishes Atlantans how to live and save and travel—with his consumer news on WSB-TV, travel tips and a daily three-hour consumer awareness show on WSB-AM, two travel columns and a consumer column in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

It hardly matters that he has none of the “sophisticated cool” expected of television newsreaders or that his lilting Southern drawl was never meant for radio. Who cares if his newspaper columns can be reminiscent of “How I Spent My Summer Vacation” essays? He tells Atlantans what they want to know.

His fans love bargains, but even more, they love Clark, and even more important, they trust him, He has an endearing Jimmy Stewart-like sincerity that makes it seem inconceivable that he could tell a lie or put on airs. Kim Curley, executive producer of his radio show, sums up his appeal this way: “People believe in Clark.”

It is minutes after 2 o-clock, and Atlanta’s consumer guru is in the WSB-AM studio gleefully relating to his nearly 300,000 listeners how he found gasoline over the weekend for 89.9 cents a gallon. To look at him is to know his joy is no put-on. He’s clad in a generic polo shirt (sans alligator), scuffed-up off-brand sneakers (why pay extra money for the privilege of wearing a company logo?) and nondescript white tennis shorts. For lunch he had a cheeseburger, and he teases his first caller by telling her that she must not be a “rock-gut cheap buyer like I am.”

But he grows serious as he listens to a phone call from a listener named Diane, who is explaining how she bought a used car and financed it through her credit union. She had checked and knew she had 21 days to get it registered and buy a tag. Simple enough, right? Until you throw into the equation the bank that held the original owner’s title. Diane waited two weeks for the bank to do the paperwork transferring the ownership. Then three weeks. Then four. Finally it arrived, about six weeks after the fact. And when Diane went to get her tag, she was hit with a $21 late fee.

Twenty-one dollars. No big deal to anyone. Except Diane. And, now, Clark Howard. “The first thing I want you to do is contact the director of the tag office, explain what happened and see if they will waive the late fee,” he tells her. His voice is soothing and compassionate: friend, not radio talk show host. “Try to reach them this afternoon and call me back to let me know what happened. Okay?”

Despite his soft tones, Howard’s dander is raised. He has received call after call to his radio show about the bank, problems arising out of its recent acquisitions. He has resolved to pound them on the air until they clean up their act—not only are customers encountering problems, but he thinks the bank’s attitude is rather cavalier. Without mentioning the bank’s name (he cautiously won’t name a company on the air unless he believes he’s really got them nailed), he talks about a previous caller who wanted to pay off her car loan, but no one could find the loan documents.

“Now we have Diane, who ends up a victim and a money loser,” he says, habitually emphasizing certain phrases in many of his sentences as a teacher might, “She was not even a customer of this giant monster bank, and she loses. The people at this giant, monster out-of-state bank say there’s no problem with this merger, that they just acquired assets. Then why are we getting all these phone calls from people who are having problems? Could it have something to do with the fact that the bank is also buying customers who are people?”

Howard hits a button and goes into a commercial break. Off the air he says one listener claimed to have actually reached the president of the corporation in Charlotte, who insisted there were no problems in Atlanta.

“Oh yeah?” the person retorted. “You must not be listening to Clark Howard.” The president was baffled. “Who’s Clark Howard?”

It’s a question he likely won’t ask twice.

Clark Howard, 41, may well be the best consumer advocate in the business and the most trusted figure within earshot of WSB.

His radio show receives so many calls that Howard convinced WSB to start a consumer action center to help the hundreds of people each week who couldn’t get through. The center opened in 1993 with a staff of one. Howard went on the air, asked for volunteers, and the center is now overrun with 120 loyal disciples who donate their time and field more than 2,000 distress calls a month from people victimized by everything from shady used-car salesmen to botched surgical procedures. And the calls come in from as far away as Taipei.

Howard’s top-level staff is a mostly female club, and they clearly mother him. “On one hand, he’s so savvy and so worldly,” says Beverly Molander, the center’s director for the past two years. “And then he’s so eggheaded and so naive; there’s really this innocent quality to him.”

Adds Kim Curley, “He loves to come in and make fun of himself: ‘I’m such a flake, I’m such a goof-off.’ It’s so cute.”

If you want to see him flustered, just ask Howard about his reputation for attracting some of the most desirable women in Atlanta prior to his marriage (his second; he has a daughter from a previous marriage) in October 1995. He starts to answer, then abruptly stops. His face turns crimson, and he looks terribly uncomfortable during a very long, 20-second pause. Then, finally: “Boy, I’d better be careful what I say.”

That’s followed by another pause. “Being single was a lot of fun,” he says, carefully measuring his words; at the same time, he seems ready to burst out into embarrassed laughter. “I did seem to meet a lot of wonderful women. I really had a great, great time. Some people think I’m nuts to have gotten married, but I’m nuts about the woman I did marry, and that’s what made me settle down.”

He met his wife, Lane—once immortalized in the pages of this magazine as “Boortz’s Babe”—when she worked for Howard’s colleague at WSB, archconservative Neal Boortz. “So often, people [in the media] have an attitude problem,” she says. “I was really taken aback by how genuine Clark was, and how friendly. We were friends, and then he asked me to go out to dinner, and we had a really good time. We went out again, and after that I was really smitten.”

She soon learned what others close to Howard already knew. “He’s exactly what you hear on the air,” says Kim Curley. “He’s a very polite Southern gentleman. There’s never been a moment when he acted differently.”

“The greatest thing about him is something his dad taught him,” says Lane Howard. “Always treat everyone as if they’re the most important person in the world. Treat them with respect. If we’re in a restaurant, and they have a name tag, he’ll always look them in the eye and call them by name. And it’s amazing how that makes people feel.”

Howard likes to joke that he must have been adopted or else dropped on his head at an early age—he’s an obsessive bargain hunter, but hardly a child of poverty. “I had a total silver spoon growing up,” he says. He was born in Atlanta, the baby in a family of four children, six years younger than his closest sibling and feeling much like an only child. His maternal grandfather founded the Lovable bra company, and his uncles later took it over, with his father in management. “I grew up Old South wealthy. I never had to make my bed. I never had to fix a meal. It was a very cushy life.”

A defining moment came during his freshman year in college—the company fell on hard times and his father lost his job. Howard worked his way through school in Washington, D.C., including a job in public housing and handling consumer complaints for the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. He also set up a campus chapter of a consumer group affiliated with Ralph Nader. “I think his dad losing his job really affected him,” says Curley. “He understood that money doesn’t just appear, and it became a real goal for him to help people.”

Howard eventually returned to Atlanta with a master’s degree in business, and instead of finding a fast-track job with a major corporation, he went to work for Literacy Action. Three years later he left and opened a travel agency, because he loved to travel and it was a cheap business to start up. His goal was simple: make enough money to never again have to worry about financial distress.

The timing was perfect. The agency opened in late 1981 in the wake of airline industry deregulation; ticket prices had dropped and ridership was soaring. Within six years Howard owned five branch offices, and a group of investors from Ohio made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. He sold the agency and retired to a life of leisure at the ripe old age of 31.

“I never really intended to work again,” he says. “I was a complete bum. Went to Florida for a while, lived in a resort. Carne back to Atlanta, and I was swimming two miles a day and watching reruns on TV, and that was it. Completely out of the blue one day I got a call from a producer for WGST-Radio asking if I would be a guest on their travel show on Sunday. Three or four weeks later they had me back again. Then they asked if I would like to be a guest every Sunday.”

A few months later, in early 1988, Howard walked into the studio one afternoon and the host was missing. “Didn’t anybody tell you?” the newscaster said. “There’s been some cutbacks. You’re now hosting the show.” When WGST decided to begin a one-hour consumer call-in show, the station manager called him at home for advice. “Clark, I’m looking for somebody who can answer consumer questions like Clark Howard answers travel questions,” he said.

“Well,” Howard responded. “That would be me.”

By 1991 he had been lured away to competitor WSB and was on his way to becoming a cottage industry and a star.

Clark and Lane Howard were supposed to go to Greece for their honeymoon. And between his investments and real estate deals and sale of the travel agency, he’s set for life, with some pretty big bucks in his back pocket, enough to afford the trip of a lifetime.

And what does he do?

At the last minute he found a great deal to Hawaii, so they went there instead. And, of course, Howard shared the tip on his radio show and in his newspaper column. When the couple boarded their plane, they were besieged by grateful passengers who had bought their tickets on Howard’s advice.

During the honeymoon he and his wife made their way to a beach so out-of-the-way that the horizon was empty of people. They sat back and relaxed, enjoying the illusion that they were on an island all their own. Then they began to notice another couple making their way up the beach. The couple walked right up to them and greeted Howard as though they’d known him for years.

“We really like your show!” they said. “And thanks so much for the great price to get out here.”

He’s recognized everywhere he goes in Atlanta, and as soon as people spot him, it’s as though they begin lining up to ask his advice. “The biggest change I’ve made in my life is I love eating out, and we eat at home now, for privacy,” he says. “I don’t look at it as a bad thing that people want to ask questions. It means we’re doing well at what we do. But I love it when I travel, because nobody knows who I am.”

Lane Howard says with a laugh that she’s grown accustomed to what it takes to be her husband’s traveling companion: patience in bundles.

“The only criteria for our house was that it had to be within spitting distance of the highway, because Clark believes you have to be near the airport,” she says. “He has to be able to fly out at a moment’s notice. There’ve been times when he’s called me up and said, ‘We’re going to New York tonight; be ready in an hour.’ Not only do I have to keep something packed, but I’m only allowed to have a carry-on. I guess he hears so much of that on his show, luggage being lost or ruffled through. Can you imagine trying to get a week of skiing clothes into a carry-on? I’ll look like a refugee because I’ll have on, like, five layers when I get on the plane.”

Her husband also dislikes reservations, preferring to scout out hotels, looking for the best location and, of course, the best price. “In Italy we were rolling our little carry-ons down a cobblestone street, looking for a hotel,” she says. “And the most expensive place was the first place we went to. And he went, ‘No, no, we can’t afford that.’ It was something like $75. So we went to every other place in this little village. Nowhere else to stay. It’s now about 10 o’clock at night, and he’s so defeated: ‘I can’t believe we have to stay there.’”

Even at home he never breaks out of the mold. Before meeting Lane, he didn’t go to movies. He didn’t go to concerts or plays. If he’s not traveling, he’s sitting at the computer or studying the financial section of one of the four newspapers he reads each day. Or else he’s out shopping, engrossed in his perpetual search for the ultimate deal. Should he meet a stranger in the course of his business, his impulse is to reach out and confide to his new acquaintance just how to get a great deal.

For example, he asks his interviewer his shoe size.

“Good,” he’ll exclaim when he hears that it’s a 10 1/2. “If you ever have to have dress shoes, I’ve found the coolest thing.”

At such times he doesn’t so much speak as effuse, his voice filled with so much boyish enthusiasm that he’s almost breathless at the end of the sentence. “It’s a shoe store that sells Bass Weejuns. And I buy them for $34 a pair, because I’m buying them in the boys’ department instead of the men’s deportment, It’s a marketing thing. It’s still a men’s shoe, but kids’ feet have gotten so much bigger, they go up to size 11 in the boys’ department. So I buy all my dress-up shoes there.”

It’s just before 4:30 on the afternoon of Diane’s call about the problems with the big bank, and Clark Howard is in the last hour of his radio show, reading a promo for that evening’s Braves broadcast on WSB. About halfway through there is a sudden burst of laughter from an adjacent room, where Helen Lovern screens the dozens of calls Howard receives each afternoon. And sitting next to Howard, Kim Curley has her hand over her mouth, or else she’s going to start laughing, too.

Howard shoots them a look of feigned exasperation as he announces that the broadcast will be sponsored by NationsBank, the very bank that he has spent the earlier part of the show lambasting.

Minutes later the irony just gets richer. Lovern walks into the studio during a commercial break to tell him that Diane is back on the line. Earlier, Howard had encouraged her to contact the tag office and ask them to waive the late penalty because the bank, in fact, had been tardy. She’s calling with the news that they won’t refund the money. With that, Howard takes his cue and for the first time names NationsBank on air, mounting a full offensive, even though the target just happens to be a WSB sponsor that he promoted only five minutes earlier.

He doesn’t worry—he has a clause in his contract stipulating no sacred cows, WSB advertiser or not. “Now, Diane, what I think you have a perfect light to do is to march in a NationsBank branch and get $21 out of those people,” he says.

Then he smiles.

“Now, the year that you’re able to get that out of this big, giant bank, I will be interested in healing. You are just another piece of collateral damage from another monster bank gobbling up another of our local institutions. I feel bad for people who suffer from these mergers and the banks say, ‘Well, there’s just going to be some casualties along the way.'”

It’s a glimpse at the other side of Clark Howard, one that’s far removed from the flake. It’s the side that’s incredibly savvy and strongly principled and, most of all, compassionate, He cares. It’s genuine. It matters to him that Diane is out $21 through no fault of her own. And it’s the final ingredient of his success.

“When I don’t have that compassion anymore, I’ll have to go,” he says later. “Eventually it’ll be squeezed out of me, and I’ll know when that is—the person whose situation I’m really concerned about today, the time will come when I’ll hear that same thing, and I’ll shrug. That’s when I’ll know I’m done.”