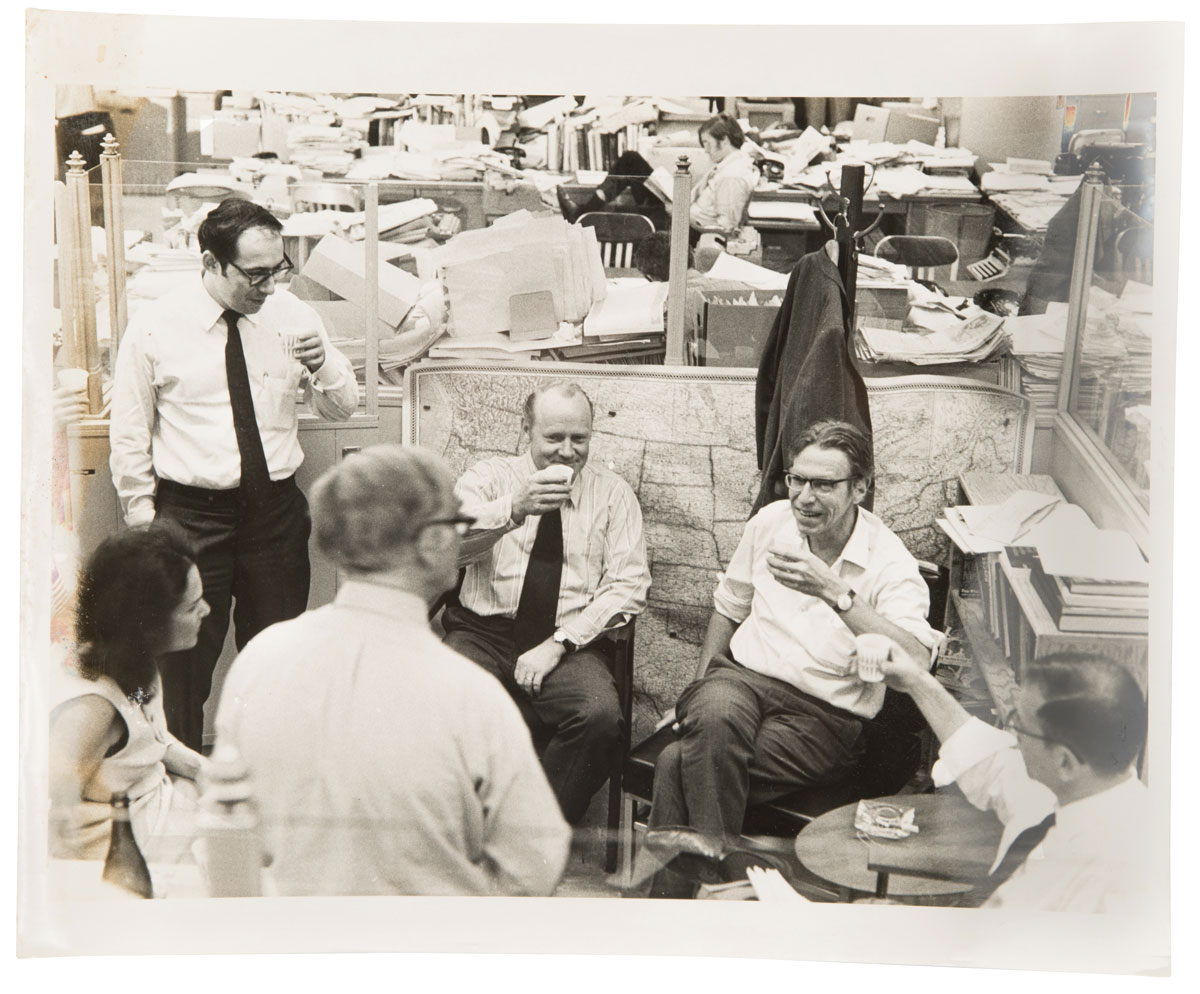

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

The story—but only part of it—has endured for five decades: In 1965 Jack Tarver, the president of Atlanta Newspapers Inc., was so worried about alienating white readers (and so cheap) that he refused to let the Atlanta Constitution or the Atlanta Journal send a reporter to cover the escalating racial showdown in Selma. As voting rights legislation gathered momentum in Washington and supporters flocked to that small Alabama town, Gene Patterson, then editor of the Constitution, and Ralph McGill, its publisher, agonized over the restraints. McGill suggested they salvage their own reputations by hopping a bus to Selma. To his later regret, Patterson talked McGill out of it.

Now we know even more about the deep professional embarrassment Patterson and McGill felt. Among the many revealing discoveries inside about 50 boxes of Gene Patterson’s papers—which recently arrived at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library at Emory University as a gift from the Patterson family—is a confidential memo that a despairing Patterson wrote Tarver on March 12, 1965, five days after Bloody Sunday in Selma.

The Constitution had just suffered a huge loss: Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter Jack Nelson had left to join the Los Angeles Times as Atlanta bureau chief. Among his former Constitution colleagues, “Nelson has been wondering aloud, where our people can hear him, why Los Angeles covers the South and Atlanta doesn’t,” Patterson typed on an interoffice memo to Tarver. Then he revealed an even greater humiliation: Tom Winship, editor of the Boston Globe, had called McGill “asking if our man in Selma could write him a special and McGill lied to him, saying our man was just back and busy, so McGill wrote six pages for Boston himself.”

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

Compelling narratives of history are built on the discovery of cloistered memos like that, written at critical times like those. The papers, which Patterson housed at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies in St. Petersburg for many years, spill over in hundreds of confidential memos, personal letters, comedic repartee with fellow journalists, gossip, and accumulated materials of his estimable life and career.

Patterson spent the last four decades of his life in St. Petersburg, where he served as both chairman and CEO of the St. Petersburg Times and chairman of the nonprofit that owns the paper, the Poynter Institute. In the summer of 2015, two years after Patterson’s death at 89, officials at Poynter began looking for a more accessible, permanent home for Patterson’s papers. While visiting Atlanta that June, Roy Peter Clark, then senior scholar and vice president of Poynter, asked me if Emory might be interested. I had known and revered Patterson. I had studied and written about him. Yes, I replied, of course.

Atlanta Journal Constitution via AP Images/Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

The minute the Patterson Papers were wheeled into Emory’s Woodruff Library in September, then to the 10th floor Rose Library, this great and ebullient wordsmith, through his collected works, was reunited, as if through reincarnation of the newsroom, with journalists who shaped his career and animated his daily life. The Rose Library holds the papers of Journal and Constitution staffers McGill, Harold H. Martin, Celestine Sibley, Jack Nelson, Henry Grady, Margaret Mitchell, Patricia LaHatte, Keeler McCartney, Reese Cleghorn, Pat Watters, and Ernest Rogers; New York Times reporters Claude Sitton and John Herbers, who worked out of the Constitution and Journal offices; Newsweek reporters Bill Emerson, Joe Cumming, and Marshall Frady—not to mention his friends in the business and civil rights communities.

I first met Patterson in 1995 in Atlanta at the annual Popham Seminar, a lively and liquid gathering of reporters who had covered civil rights. The gathering was named for the New York Times’ first correspondent based in the South, Johnny Popham, himself a regular attendee. I was researching The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, which Gene Roberts and I wrote (Knopf, 2006). These raconteurs enchanted me—none more than Patterson, who, in my interview with him, hooked me with his opening story about an early confrontation he had as a newspaper writer.

In 1942, when Patterson was a sophomore attending North Georgia College in Dahlonega and writing for the military school’s student newspaper, the Cadet Bugler, Governor Gene Talmadge had begun meddling in university faculty appointments across the state, provoking the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to revoke the entire university system’s accreditation. Patterson uncorked an editorial blast at the governor. He was abruptly invited to the office of the college president, Jonathan C. Rogers.

“Did you write this editorial?” Rogers asked. Patterson said he had. “Did you write this, that the governor of this state has ‘placed our diplomas in jeopardy’?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Cadet Patterson, how do you spell jeopardy?”

“J-e-a-p-o-r-d-y,” Patterson replied.

“That’s wrong. That’s wrong. It’s j-e-o-p-a-r-d-y.” Patterson figured he would soon be deported back to South Georgia.

Then Rogers laughed, Patterson recalled, gave him “a big sunny smile and said, ‘That’s all, Cadet Patterson.’ And the smile told me he approved of the editorial . . . I always remembered how to spell the word after that.”

Patterson finished up at the University of Georgia, served as a captain in General George Patton’s Tenth Armored Division, and began a journalism career that took him first to newspapers in Temple, Texas; then to Macon; then to United Press bureaus in Columbia, South Carolina, New York, and London. He was in London on May 17, 1954, when U.S. editors asked him to get reaction from a traveling Atlanta editor, Ralph McGill, to the unanimous Supreme Court decision striking down school segregation in Brown v. Board. He did, and it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship that was renewed when Patterson joined the Atlanta papers in 1956, becoming editor of the Constitution in 1960.

For eight of their 12 years together, these smart, knowledgeable, voluble men worked on the fifth floor at 10 Forsyth Street downtown, each writing a column seven days a week and each pushing the South to rise above its past and confront its present with a more open mind. They spoke to the South, scolded it, sometimes apologized for it, and sometimes just explained it—each earning a Pulitzer along the way. McGill, writing on the front page everyday, had a global view and was better known; Patterson, writing everyday on the editorial page, was more consistently the stronger writer. When Patterson quit in September 1968 to join the Washington Post as managing editor, McGill expressed his love and admiration for Patterson in a melancholy column titled “An Essay on ‘Separation.’” Four months later, McGill died of a heart attack.

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

Patterson’s papers take us back to a time when a strong-willed liberal editor could clash publicly with a resolute conservative U.S. senator, Richard Russell, or a governor, Ernest Vandiver, both of whom were committed to racial separation, while corresponding civilly and helpfully in private. When Dick Rich of Rich’s Department Store could invite Patterson to his home for late-night drinks to lament the damaging boycott at his store. When mayors could share secrets. And when readers could challenge editors and get a personally typed response.

“I am convinced that you and Mr. McGill must bear a considerable share of the responsibility for the lawless conduct of Negroes in Atlanta and the State of Georgia in the integration controversy,” attorney John W. Crenshaw of Atlanta wrote Patterson in June 1963. Replied Patterson: “I regret your disapproval of our policy but I appreciate your expression of your own views.”

Patterson’s writing inspired mailbags of passionate responses. In 1962, after white supremacists burned and destroyed three black churches in Terrell County in Southwest Georgia, Patterson used his column to raise money to rebuild the churches. The $10,000 he raised came in worn dollar bills, quarters and dimes taped onto hand-scrawled letters, and was combined with $50,000 raised by others. Patterson’s papers show the names of hundreds who contributed.

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, Patterson was mowing his lawn on Normandy Drive, off West Wesley in Atlanta, when his office called with the news that the Ku Klux Klan had bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four black girls. Patterson raced to the Constitution office at Five Points and wrote what would become his most remembered column, “A Flower for the Graves”—557 words so compelling that Walter Cronkite asked Patterson to read it on the CBS Evening News. Patterson learned the power of television when more than a thousand letters and telegrams flooded into his office. Many are now here.

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

His Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing in 1967 triggered another surge of letters expressing respect and affection. But by then, Patterson was tired of struggling with Tarver. The word got out that Patterson was itching to leave and he soon had many suitors, including the new editor of the Washington Post, Ben Bradlee.

Patterson’s papers from the Post era show his influence inside a newspaper that was rapidly achieving national importance. His memos were blunt, demanding that reporters get “The Other Side” of stories. “Any time a reporter writes about a man’s positions and motivations without checking with the man involved, he may as well turn in a retraction along with his copy,” Patterson wrote to a Post editor after detecting that omission in a 1970 story. It was on Patterson’s watch that the Post, in defiance of the Nixon administration, published the Pentagon Papers in 1971, which outlined the secret history of American military involvement in Southeast Asia.

Photograph by James A. Parcell

Histories of the Washington Post have told of the strains that developed between Bradlee and Patterson, but the words between them have not been known until now. Patterson’s papers include his resignation letter and his reasons for leaving. “Because of the limited grant of authority you have delegated to me, the strength of my position has depended solely on the degree of closeness, support and respect you made evident. I do not now feel adequately supported. In that one, crucial sense, I consider my standing before the staff to be irretrievable and my departure necessary . . .” He wrote without rancor, he said. Responded Bradlee: “I want to handle this in a manner commensurate with my respect and affection for you. That will be hard for my respect and affection are without flaws.” He suggested they “get a little drunk” and “cry a little.”

Hamilton Holmes.

Who’s Who:

The Mayor: William Hartsfield

Vandiver: Governor Ernest Vandiver, who had pledged “not one” black student would be admitted

Hollowell: Donald Hollowell, the attorney representing Hunter and Holmes

Henry Grady: The old Henry Grady Hotel, where the Westin Peachtree now stands

Twitty: Frank S. Twitty Sr. of Camilla, who was then a member of the Georgia House of Representatives and served as Gov. Vandiver’s floor leader

Sanders: Future governor Carl Sanders, then a state senator and president pro tempore of the Georgia Senate

Bob Woodruff: Coca-Cola’s then chairman

Eisenhower: Dwight Eisenhower, the former president

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

Patterson, who spent his greatest number of years at the St. Petersburg Times and the Poynter Institute after the Post, also played a role in one of the biggest scandals in journalism history, and his papers include files on it. In 1981, as a member of the Pulitzer Prize board, Patterson was troubled by a Post submission that a Pulitzer jury recommended as one of three finalists for the feature writing prize. The story, “Jimmy’s World,” by Janet Cooke, was a gripping account of the life of an eight-year-old heroin addict in D.C. Patterson, who by then was editor and president of the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times), argued against awarding the prize to Cooke and abstained from voting. He would write later that he found the story “unrealistic . . . an aberration if true, and not a story of larger meaning.” He also had argued that the Post should not have published the piece until they had attempted to save the child. He was outnumbered. Patterson’s instincts were right; Cooke soon acknowledged that Jimmy did not exist, and she was stripped of her Pulitzer.

Photograph by Raymond McCrea Jones

Patterson and I continued to see each other on occasion. As many of those giants from the Popham seminars began to pass on, Patterson was everyone’s choice as the eulogist. Then he, too, was beginning to fade. But he was determined not to go before finishing the most ambitious book imaginable. After learning at age 88 that he had about a year to live, he began editing the Old Testament. He wanted to make it tauter, easier to follow, less rambling.

In 2012 he published Chord and sent me a signed copy. I wrote him back, praising him for the masterful job he’d done in “clearing the sagebrush (or maybe it was kudzu) of verbiage that for years has obscured the path, the story, the bright narrative thread that leads to the word of God.”

His papers will speak to scholars and journalists for generations to come. But here, he gets the last word. Patterson’s response to my letter arrived less than a week before he died. The opening line was all I needed: “Your praise sends me up the road a happier man. Thank you.”

Collection: Eugene C. Patterson papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

This article originally appeared in our February 2017 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)