Photograph by Matt Moyer

The students of Utopian Academy for the Arts are being called on the carpet. Yesterday, their middle school mischief found the classic victim: a substitute teacher. The seventh-grade science room grew so loud that the classes on either side could hear the commotion through the walls.

Today, as they do every morning, the children have assembled in the cafeteria, with its red and blue cinder block walls and folding tables arranged in long rows, Hogwarts style. The whole school is here—all 180 students. The girls from Mr. Henderson’s class. The boys from Ms. Terry’s. The girls from Mr. Moore’s. The boys from Mr. Farrior’s. It is 7:55 in the morning; the school day won’t end for another eight hours, and many students will remain on campus until 6:30 p.m. This is a charter school, so Utopian Academy plays by its own set of rules. Eight-hour school days. Classes every other Saturday. A longer school year. A tougher curriculum. Dance, music, theater, and arts for all. And a rigid code of conduct.

“Good morning,” says a man from the stage. His name is Frederick A. Birkett, and he is not smiling. Birkett looks precisely how you’d imagine a former military man who went into academia might: bow tie, spit-shined shoes, ramrod posture. Just over a year ago, Birkett was an education professor at the University of Hawaii. But then he learned about this upstart school in Clayton County, Georgia, where the school board was so dysfunctional that the entire system lost its accreditation a few years ago. Birkett had never heard of such a thing, and this is a man who knows something about schools; he’s got a master’s in education from Harvard and ran pioneering charter schools in Harlem, Boston, and Kailua, Hawaii. When it comes to charters, he literally wrote the book—Charter Schools: The Parent’s Complete Guide.

Now, with every pair of eyes on him, he makes his point. “I left sunshine and blue skies and 80 degrees every day to come here. I love coming here every day. We love having you here. But you need to value what you have at this school.”

Principal Birkett holds up a red sheet of paper, like a World Cup referee. “Most of you will never see one of these,” he says. “But if you do, you need to know it’s going in your file, and we are talking with your parents or guardians.” What happened yesterday, he explains, won’t be tolerated. Not here. Not at Utopian.

Then he dismisses everyone, except for the seventh graders from the substitute’s classroom. “Come up to the front,” he says. Two dozen boys cluster at eight tables near Birkett’s feet. “You are here because someone in your life wanted you to have a better opportunity. Our goal is to get you ready for high school and get you to college.”

In the second row sits Giani Anderson. He is 12 years old and has been up since four o’clock this morning. His mother just started a janitorial business, and today he helped her with a cleaning project before she dropped him off at school, on her way to her other job at the Division of Family and Children Services call center. His stepfather works two jobs as well—in construction and in the shipping department at PetSmart. After school today, Giani will go to basketball practice, then football practice, and then he’ll do homework. He won’t go to bed until midnight.

Every month, Birkett reminds the boys, the school selects two students to represent Utopian at the Georgia State Charter Schools Commission meeting. These are students who embody the ethos of the school. His eyes settle on Giani. “Giani Anderson will go to the state Capitol this month because Giani has shown he takes this seriously.”

The only thing worse for a seventh-grade boy than being called out for bad behavior is being called out for good behavior. As his classmates turn their heads to look at him, Giani ignores them. From the stage, Birkett is imposing his sentence: a few boys suspended at home, three suspended in school.

“Now go to class.”

Photograph by Matt Moyer

Every morning, Artesius Miller stands sentinel in the driveway in front of Utopian Academy. Tires crunch on gravel, cars come to a stop, and students tumble from backseats with backpacks and gym bags slung over their shoulders. Miller, Utopian’s founder and executive director, greets each child by name.

“Good morning, Elijah. Let’s make it a great day.”

“Good morning, Christina. Let’s make it a great day.”

Miller believes in the power of a firm handshake and direct eye contact. “It’s a confidence booster,” he says. “And it sets the tone for the day.” Miller likes to remind Utopian students that great days are intentional—that they are made.

“Good morning, Jayland. Let’s make it a great day. Ready for basketball practice?”

For Miller, the morning ritual is equal parts encouragement and vindication. Utopian Academy’s journey through regulatory red tape and school board turf battles began half a decade ago. Miller’s ambitions—and the obstacles he encountered in Clayton County—parallel a larger struggle over charter schools in Georgia and their role in a state where public education is a punchline: Georgia ranks 47 for high school graduation, 46 for SAT scores, and seventh in the nation for declining teacher salaries. Charters—publicly funded schools that are exempt from certain regulations (in curriculum, calendar, and teacher certification, for instance) in exchange for meeting specific goals (usually test scores)—are hardly the answer to all the problems in public schools, but they have been effective in many cases. Still, in many areas of Georgia, opponents have approached charters with not only skepticism but overt hostility.

The charter movement attracts its fair share of dilettantes, who believe their outsider status imbues in them a wisdom that will allow them to succeed where conventional public school models—laden with bureaucracy and legacy—fail. Miller is passionate about schools, but he is no dilettante. His grandmother was a teacher, and his great-grandparents founded a school in Mississippi. On graduating from North Atlanta High School, Miller earned a Gates Foundation Millennium scholarship that paid for his entire Morehouse College education. He worked in finance at Goldman Sachs in New York City and JPMorgan Chase in Chicago until he was “called,” as he puts it, to education. He enrolled in Teachers College of Columbia University, holding down one part-time gig tutoring at a charter school and another as a “college access coach” for the New York City Department of Education and in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Charged with navigating high school students through the college application process and boosting enrollment among young men and minorities, Miller soon realized that for many students, junior or senior year is far too late to prep. High school is too late. He thought about what it would take to launch 12- and 13-year-old boys on the path toward college.

Photograph by Matt Moyer

At the same time, Clayton County was making national news when its 50,000-student school system, on probation for the previous five years, lost its accreditation—a first for any U.S. school district in four decades. In August 2008, then-governor Sonny Perdue removed four members from the school board. Students were left in limbo, with scholarships and graduation in jeopardy. Parents (those who could afford it) pulled their kids out of Clayton schools—or simply moved. Within weeks, more than 350 students had transferred from Clayton to Fulton schools. Already declining property values plummeted. Even though accreditation was provisionally restored within a year, the schools remained on probation and today continue to underperform. In 2014, only 60 percent of Clayton County’s high school students graduated, a rate that is 12 points below the state average. Of those Clayton students who graduated the year before, only 29 percent earned the grades needed to win the HOPE Scholarship, compared with 46 percent of their Fulton County counterparts. That year, the average SAT score for Clayton County students was 1,259—which is 145 points below the state average and 239 below the national score.

Academic success and income have been shown to be directly correlated; in Clayton County, 25 percent of all residents—and 37 percent of all children—live below the poverty level, and the unemployment rate is almost triple the national average. Schools that have a high percentage of economically or otherwise disadvantaged children are labeled Title 1 under a federal designation. In Clayton County, the entire school system is designated Title 1. So many children—85 percent—qualify for free or reduced lunch that Clayton simply serves free lunch to everyone. It is these types of statistics that led many to conclude that few metro school districts in America more needed to radically rethink the way they educate their children than did Clayton.

Charter schools—created to foster radical new ideas—have been authorized to operate in Georgia since 1993. But charters needed the blessing from local school boards, which is sort of like asking taxi companies to welcome Uber with open arms; the very existence of charter schools became a tacit admission by public school officials that they could not do their jobs. Perhaps for that reason, Georgia was slow to embrace charters; in the 2007–2008 school year, there were only 71 charter schools in the state.

In 2008 the Republican-led General Assembly created a state commission and gave it the authority to approve charters that local school boards denied. (The irony of Republicans, champions of states rights, essentially undermining local school boards was not lost on anyone.) Court challenges followed, and in 2011 the Georgia Supreme Court declared the state commission and the law that established it unconstitutional, putting 16 state-approved charter schools in jeopardy. Governor Nathan Deal—a charter school supporter—provided emergency funds for some of the schools, but with the commission, well, decommissioned, there was little oversight for the state-chartered schools during the next two years.

Photograph by Matt Moyer

It was against this backdrop that Artesius Miller moved back to Atlanta, taking a job at Mosaica Education—a for-profit firm that manages public and private schools in the U.S. and overseas—and then for the Steve and Marjorie Harvey Foundation, which runs programs for fatherless children. Miller, who is earning a Ph.D. in educational administration and policy from the University of Georgia, met Clayton parents eager for an alternative for their children and presented his plan for Utopian. He selected Clayton as the location given the obvious need there, and because of the specific needs of one group of students. If Clayton’s graduation rates were lousy, they were downright depressing when it came to young black boys: In 2010, only one of three black males earned a high school diploma.

In May 2011, Miller brought his petition for Utopian to the Clayton school board. He proposed a boys-only middle school that would pair academic rigor with strict discipline. Miller’s petition was denied. Delphia Young, the school system’s director of special projects, said that the proposed school was not unique and sent a letter to Miller and school officials with a laundry list of questions about the proposal.

The next year, Miller responded with a proposal incorporating two single-gender academies and a STEAM—science, technology, engineering, arts, and math—curriculum. In June 2012, he went back to the school board, accompanied by dozens of sign-waving supporters. At the recommendation of school superintendent Edmond Heatley, the board again declined Utopian’s petition. Board chair Pamela Adamson told Clayton News Daily that Miller’s plan was “just not something that the district is not already offering,” and suggested Miller go someplace other than Clayton.

Charters were a hot topic in Georgia that year. The 2012 fall election ballot included a constitutional amendment that would reinstate Georgia’s charter commission. Opponents of the amendment made for an improbable alliance: Tea Party activists; the state PTA; Georgia school superintendent John Barge; and civil rights veteran Joseph Lowery, who claimed it would result in schools resegregating. Supporters included Republican lawmakers, eager to tout expanded school choice, and advocates like the Georgia Charter Schools Association. Funds for a massive pro-amendment ad campaign poured in from national supporters, among them Walmart heiress Alice Walton and J.C. Huizenga, the founder of for-profit charter school operator National Heritage Academies.

Fifty-eight percent of voters approved the amendment, and in Clayton, the measure won approval from 71 percent of voters, the highest margin in the state. Across Georgia, the amendment received strong support in counties with majority black populations, places where public schools had chronically lagged and where local boards had been particularly hostile toward charters.

In May 2013, Miller made his third appeal to the Clayton school board. The district’s new superintendent, Luvenia Jackson, recommended denying the petition, and in a 4–3 vote, the school board followed her bidding. “We are not unfriendly to charters, but we will not approve one that does not provide a unique experience,” says Adamson, the board chair. Miller and his supporters “are all well-meaning people and want to do the right thing, but you can’t have a charter just because you claim ‘the public schools are failing.’” Jessie Goree, one of the three board members who voted in favor of Utopian, says that failing schools are precisely the reason she cast a yes vote. In Goree’s view, the Clayton system is complacent, satisfied with incremental gains. “If you are happy gaining a few points here and there, you aren’t improving it. So you get the graduation rate up to 60 percent—that’s nothing to be proud of.”

Denied three times by Clayton County, Miller appealed to the newly reinstated State Charter Schools Commission. “It was a high-quality petition, and Miller was really prepared,” says Bonnie Holliday, the commission’s executive director. Utopian was approved unanimously in 2013, the only petitioner out of eight to get an okay.

But time was short; Utopian had just nine months to open. First on the agenda: adjusting the budget. The 2012 amendment removed any local funding from state-chartered schools. Charters like Utopian get federal and state funds comparable to other schools in their districts, but instead of revenue from local property and school taxes, they are given an allowance from the state based on the average of the five lowest-funded districts in Georgia. State charters receive on average $7,800 per full-time student, compared with an average of $9,000 per student for traditional public schools, says Holliday.

For this year, Clayton County Public Schools will receive state, federal, and local revenue that amounts to $7,561 per full-time student, according to a spokesperson for the school board. Utopian, on the other hand, will receive only $6,400 per student in state and federal funding, according to Miller. Along with lower revenue, Utopian has to cover expenses other schools don’t; as a state-chartered institution, it is not on the Clayton County school bus route, nor does it have access to any of the district’s other shared resources, such as special education programs, stadiums, or the performing arts center.

The next step after scaling back budgets: hiring Birkett, who then hired the teachers. The freedom to staff a school to best suit its needs is the greatest plus of running a charter, Birkett says. “You don’t have to take whoever the district sends you.”

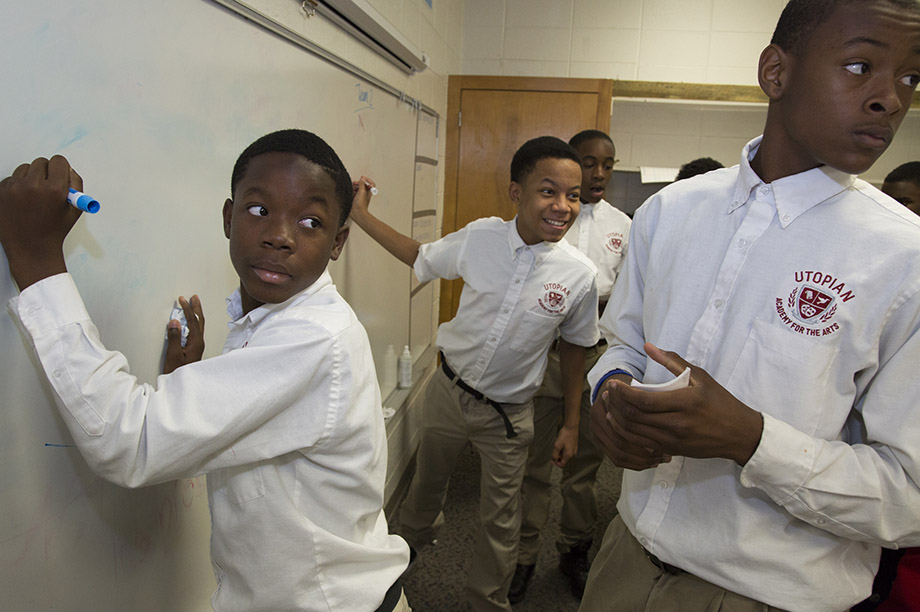

Miller signed a $9,500 per month lease for a portion of the Riverdale Elementary School complex, a 1954 building that has been added onto over the decades. It’s challenging to transform a building designed for the smallest students—tiny toilets, knee-high sinks, and low coat hooks—into a space for too-cool-for-school preteens and teens, but Utopian has tried. The hallways are brightly lit and the floors immaculately waxed. Teachers creatively repurposed little-tyke cubbies as library shelves and mastered writing on close-to-the-ground whiteboards.

Classes were set to start on Monday, August 4. On Sunday, Miller got a call from the city of Riverdale: There were problems with Utopian’s occupancy permit. Oh, and the fire department wanted to do some inspections. The students showed up and, with police and fire trucks on the scene, were turned away at the door. As one day dragged into eight, parents grew anxious.

Miller filed a temporary injunction against the city, finding an ally, Judge Matthew Simmons, who ordered Riverdale to wrap up its inspections posthaste. “This is a political issue,” the Clayton Superior Court judge told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution after the hearing. “There’s some folks that don’t want a charter school over there. And they’re trying their best to obstruct that.”

“At every step, Clayton County tried to sabotage us,” Miller says. It wasn’t just occupancy permits; when Utopian requested transcripts and test scores for transferring students, some schools sent sealed envelopes that contained blank sheets of paper or school supply lists, says Miller. It made preparation a challenge, according to Malika Gonzales, Utopian’s director of curriculum. “We didn’t know what we were getting, and we got the gamut,” she says. Enrollment at Utopian is open to students throughout Clayton, and students represent every city and neighborhood in the county, from Rex, 10 miles to the east, to Riverdale, within walking distance. Some have come from charter schools or better-performing public schools; others have come from the worst schools in Clayton and need tutoring to catch up with their classmates.

Finally, almost two weeks late, Utopian opened. By then, 120 children—out of 300 who’d enrolled in July—had found schools elsewhere. For a school that relies on per-student funding, this was a crippling blow. The question was, would it be fatal?

In Mrs. Craft’s English and language arts class, Giani is reading The Giver, Lois Lowry’s Newbery-winning saga of a 12-year-old boy’s struggle to accept his predestined role in an idealized society. (The Giver was published in 1993 and is now considered a middle school classic; if you aren’t familiar with the book, imagine Tom Sawyer wandering into Brave New World.)

“Jonas lives in a utopian society,” Mrs. Craft says. “What does that mean?”

“That it’s perfect,” one student answers.

“Why is it perfect?”

“Because there are rules to keep everything in order.”

“Let’s talk about those rules,” Mrs. Craft says. “How do they compare to our society?”

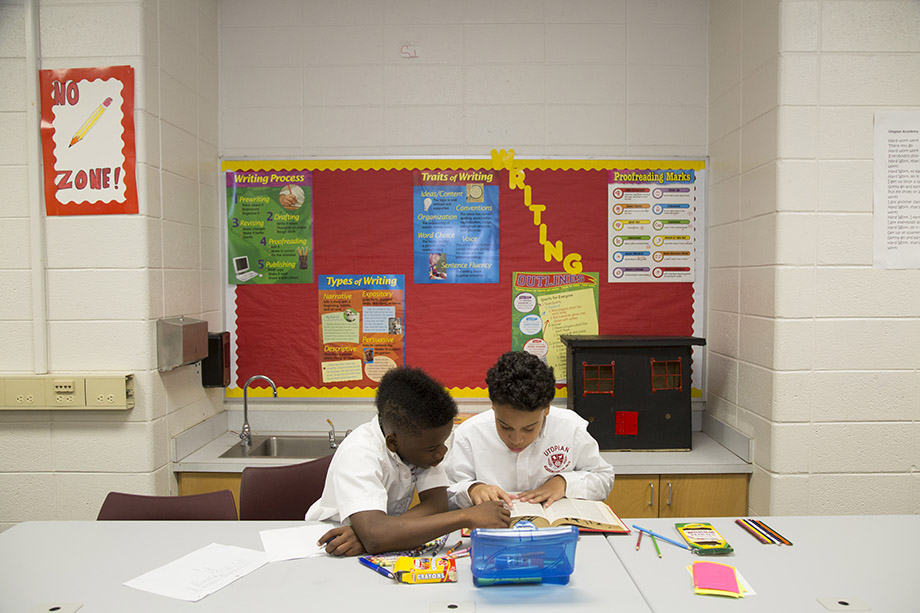

For the next 40 minutes, the boys work in pairs, organizing observations about The Giver into a Venn diagram: rules in Jonas’s society, rules in ours, rules both communities share. They flip between paperback editions of the novel and their worksheets.

Mrs. Craft tells them she has two additions to their class library: a collection of poems by Edgar Allan Poe and We Shall Not Be Moved, an account of the integration of the University of Georgia. “Who would like to check these out?” Ten boys raise their hands. She assigns the books to two students; they promise to return them by Monday.

Ebonne Craft’s “library” holds about 20 titles: Little Women; a volume from The Series of Unfortunate Events; The Boxcar Children; Treasure Island; Bud, Not Buddy; Shoeshine Girl. Utopian Academy does not yet have a real library, or a computer lab, or a reading specialist—the basics you find in any public or parochial school. And it certainly doesn’t have the fancier extras—state-of-the-art Smart Boards, high-tech labs, expansive gyms—that you find in wealthier public schools, well-heeled private schools, or even charter schools with deep-pocketed patrons. Some books in Mrs. Craft’s classroom were donated by a nearby Barnes & Noble; others she bought herself.

Photograph by Matt Moyer

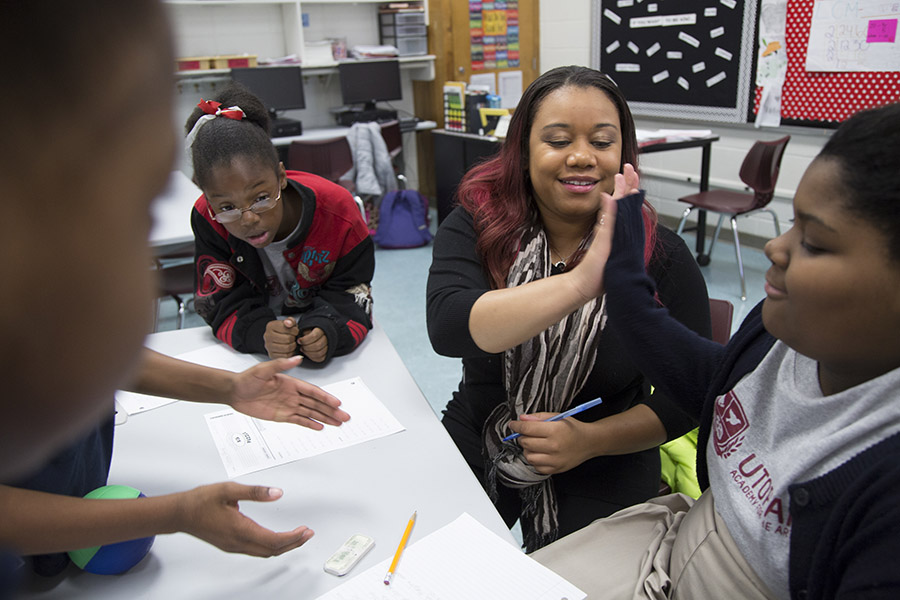

The bell rings. As Giani heads out the door, one of the rules at Utopian Academy instantly becomes visible: There are schools within this school, one for boys and one for girls. Divided by gender for math, English, science, social studies, and Spanish, the boys and girls mingle only during arts classes, assemblies, and lunch. Also evident: Puberty strikes everyone at different rates. Among the rows of students moving down the halls, the girls tower over the boys.

Giani says that the single-gender classes are something his mother really likes about Utopian; she thinks it keeps him from being distracted. He is less sure. “You can’t talk to the girls about classwork,” which makes it harder to get to know them. And then you have “a whole bunch of boys acting weird and playing too much.” Sometimes, he says, “they make me crazy.”

In Ms. Sanders’s A/V class, students still cluster by gender, boys on the left-hand side of the U-shaped row of tables, girls on the right. The students are creating a parody “Happy” video, and today, Ms. Sanders demonstrates Final Cut Pro. The students don’t have their own computers to work on, so they watch as she organizes and edits video clips on her laptop, which is hooked up to a flatscreen.

How hard is it to teach video production when students don’t have hands-on access to A/V tools? Shana Sanders sighs. “Before, I taught at schools that had resources, but students who weren’t as motivated to learn. Here, they are eager to learn.”

Photograph by Matt Moyer

Spend any time at Utopian, and it’s clear that this startup charter has the scrappy spirit that you might expect from a fledgling tech firm or a mom-and-pop. Ms. Smith, Giani’s homeroom teacher, runs the after-school cheerleading program, helps organize the boys basketball team, and teaches five Spanish classes a week. Sixth-grade social studies teacher Allan Henderson also runs the before- and after-school care programs; his day starts at 6:30 a.m., when some students are dropped off early by parents en route to work, and ends 12 hours later. “It seems like all of us wear at least three hats,” he says. “But we knew that when we signed on for this. It’s part of building something.” Henderson’s drive is paired with a sense of mission; he grew up in East Lake Meadows, the housing project once notoriously nicknamed “Little Vietnam,” and saw his best friend killed and his brother jailed. “For me, school was always a safe haven,” he says. And he knows for some of his students, Utopian offers a similar refuge.

Every three to five years, charter schools must go through a renewal process. Approval can be revoked—and schools shuttered—if chartered terms are not met. When it comes to the schools closing, “the public thinks about the academic reasons and performance goals,” says Tony Roberts, president and CEO of the Georgia Charter Schools Association. “But just as common is if there are governance issues, or the school doesn’t have the financial ability to survive.” Roberts, who watched Miller and Utopian fight to open, says that in his view, the school and its leaders are “well positioned for success.” But for any startup school, “the first two or three years can be touch and go because of financial uncertainty.”

The academic goals outlined in Utopian’s charter are modest but meaningful: to stay off the lists that designate schools as “priority, focus, or alert,” and to surpass Clayton schools by at least three percentage points on the number of students meeting or exceeding expectations on the CRCT test. These are paired with promises to look out for students’ emotional and social well-being, with individual mentors, guidance sessions, and Saturday school for those who need extra help. But achieving higher standards with a lower budget than the rest of the county’s school system won’t be easy. The previous occupant of the building that now houses Utopian was another state-approved charter, Scholars Academy, which was closed by the state commission last spring for failing to meet academic goals. Deetra Poindexter’s son, Xavier, like a number of current Utopian students, attended Scholars. She said that watching the closure of that school made her even more committed to helping Miller succeed. “We fought then, and we will keep on fighting.”

“It’s a terrible day when you have to close a charter school,” says Holliday, who pulled the trigger on Scholars Academy. “But that’s the charter school bargain: Regulators stay out of your way, and you deliver results. If charters do better than traditional schools, children benefit. If they don’t, they need to be closed.”

When it comes to measuring performance, there’s an important distinction, says Holliday: “A low-performing charter school closes. A low-performing traditional public school can operate in perpetuity.”

Photograph by Matt Moyer

Giani and his family live in Hampton, which straddles Henry and Clayton counties, meaning children with Hampton addresses are zoned for two school systems. In sixth grade, Giani attended Henry County’s Hampton Middle School. He was bored, acted out. “I got Cs and Ds,” Giani says. His mother, Twanna, was desperate for a change. The family had moved in with Giani’s paternal grandmother, and he was headed for Lovejoy Middle, a Clayton County school that has even lower test scores than Hampton Middle. Twanna Anderson checked out private schools but couldn’t afford tuition. Riverside Military Academy in Gainesville offered Giani a scholarship, but it covered only a fraction of the cost.

Now, as a Utopian seventh grader, Giani makes As and Bs. “I can notice the difference,” Anderson says. “Last year, he was not doing his homework. Now, he is really enthused about getting work done.” At his old school, she never heard about missed homework and skipped assignments. At Utopian, on the other hand, parents have to sign off on missed homework reports. Giani and his best friend, Jeremiah Lee, compete for good grades. “He has always been smart,” Anderson says of her son. “But he hasn’t been challenged until this year.”

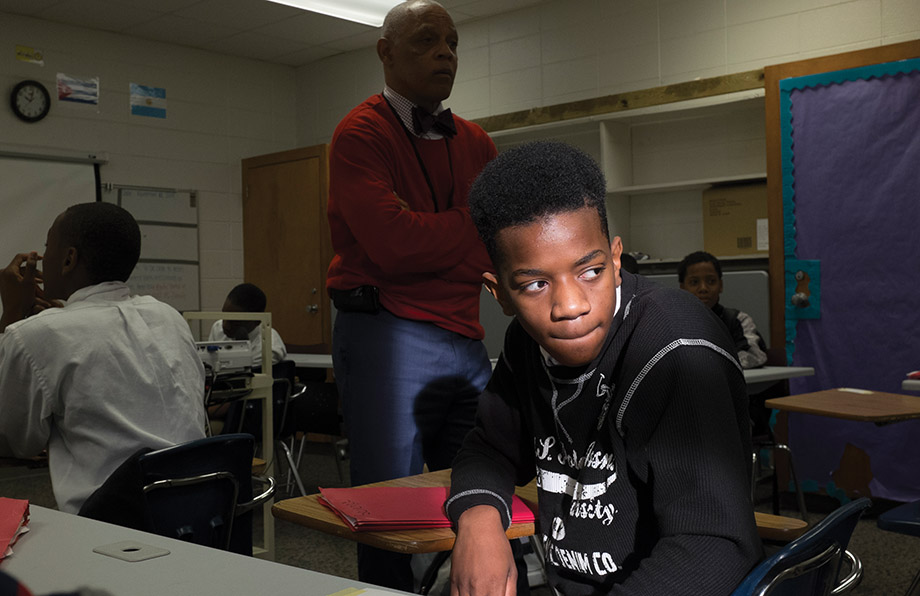

The challenges can be as profound as the debate over euthanasia in Mrs. Craft’s class (tied to a theme in The Giver) or as mundane as the notebook checks and mandatory flash cards in Ms. Davis’s science class. In Mr. Moore’s social studies class, everyone is addressed by their last name, and no one may utter an “um.” Say “um” and everyone shouts “DEAD!” Filler like “um” and “er” is just dead air, says Mr. Moore. “By the end of the year, I will break you all of the habit, and you will all speak clearly.”

Photograph by Matt Moyer

Today, Mr. Moore sits on the edge of his desk. He starts every class with a DQ—daily question.

“Today is Thankful Thursday, and here’s our DQ: What are you thankful for?”

The boys pull out sheets of paper. Some finish quickly; others struggle, pausing between each word.

“Okay, who wants to read?” asks Mr. Moore.

Giani raises his hand.

“Mr. Anderson, what are you thankful for?”

“Um.”

“DEAD!” shout his classmates.

“Well,” Giani recovers. “Well, I am thankful for teachers, for my mother and grandmother who get me up every morning, and for my friend Jeremiah who always has my back—in good times and bad.”

Another boy says he is grateful for “Mr. Moore and my male teachers teaching me to be a man.” Another says he appreciates “my Utopian brothers.”

His classmates laugh.

“Quit playing,” Mr. Moore says. “This is a serious matter.”

One boy says, “I thank the good Lord for my mom, sister, and grandmother.”

Says another: “I am thankful for still being alive, for influences keeping me out of the streets.”

A quiet boy raises his hand. “Um . . . ”

“DEAD!”

“Go on,” Mr. Moore says.

“I am thankful for being at this school. I wrote something else, but the rest is personal.”

“That’s okay,” Mr. Moore says.

“No, I want you to see this,” the boy says. He folds his notebook paper in half and walks across the classroom and hands it to Mr. Moore.

Later, I sit next to the boy at basketball practice and ask him what he thinks of Utopian. Like a number of students here, he used to attend Riverdale Middle. He says there was a lot of bullying, and “police came in with drug dogs all the time.” The classrooms were so crowded that there wasn’t a place for everyone to sit. Sometimes he dragged a chair to class; other times he just stood in the back. (Don’t just take the word of a 12-year-old: In 2011, according to the school’s accountability report, the average English class at Riverdale Middle had 31 students. The average social studies class: 34. That school year, the school issued 1,654 suspensions, meaning that there were more than two suspensions for each of the 798 students enrolled.)

At his old school, he got lots of Fs; now, he’s making Cs and even Bs. “I’m on task,” he says. His family life is complicated, with siblings and half siblings and stepsiblings, and he’s been raised by a guardian. But at Utopian, he says, he feels like people pay attention to him.

Photograph by Matt Moyer

It is students like this boy who brought Principal Birkett from Hawaii to Clayton County. “People like to talk about the importance of public education, but they don’t think about the impact of poverty. They don’t think about parents who don’t have the money to buy pencils and pens and tools for school.” Parents who go to the effort to enroll their children in charter schools, to seek something better than the status quo, he says, are just as motivated as their affluent counterparts in the suburbs and wealthy neighborhoods. “If they had the means to send their children to private school, they would,” he says. But at Utopian, few parents do; indeed, 80 percent of the students here qualify for free or reduced lunch.

When it comes to charter schools, there’s one big question: Do they work? As it turns out, charters are most effective for minority students, children from lower-income households, and those who otherwise would be in low-performing traditional public schools.

According to a study published in 2013 by Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes, charter schools do not, as a whole, perform better than traditional public schools. The researchers first compared the achievement of charter school students in 16 states (including Georgia) between 2009 and 2011. They also compared 1.5 million charter students in 27 states with “virtual matches” in traditional schools. What they discovered is that black and Hispanic students fared better in charter schools than their peers in traditional schools.

A similar conclusion was reached in a 2010 U.S. Department of Education study conducted by the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. That study compared middle school students who won admission to charter schools through lotteries with those who did not. Looking at 36 schools in 15 states, the researchers found that there was not a significant difference on math and reading test scores for “lottery winners” (who attended charter schools) and “lottery losers” (who attended traditional public schools). The study did reveal, however, statistically significant gains in math scores for low-income and/or low-achieving students after they went to charter schools, while charters that served better-off students or those who had previously done well on math tests saw an actual drop in scores.

In Georgia, charter schools as a whole outperformed non-charters in reading and math tests for the 2012–2013 school year, according to the state department of education. Locally, there’s ample evidence of the positive impact of charter schools on poor and minority students. Charles R. Drew Charter School, which serves East Lake and where 62 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch and 83 percent are black, ranked tops in Atlanta Public Schools for math for both elementary and middle school. KIPP Strive Academy, where 98 percent of students are black and 71 percent qualify for free or reduced lunch, is the top-ranked APS school for reading. There’s even an example in Clayton County: Elite Scholars Academy, which began operating in 2009, was the fourth-highest-scoring middle school in Georgia under the state’s new College and Career Preparedness Index, which was introduced for the 2012–2013 school year. In 2014, Elite Scholars graduated its first seniors, and achieved a 100 percent graduation rate.

The boys have a test on The Giver. It includes vocabulary words, which students have to define and then use in a sentence—intrigued, wheedle, apprehensive, transgression, chastise. The students also have to answer longer questions: Pick two “age ceremonies” and describe them. What is the “house of the old”?

Giani’s classmate Kai leaves about half of the questions blank but furiously fills out the answers he knows. He says he doesn’t have a copy of the book and didn’t read all of the chapters that were assigned. At the next desk, a boy with lighter skin and a smattering of freckles stares at his test sheet but barely writes. Giani leans over his desk, his head resting on one hand. He answers all of the questions but takes a long time with some.

“If you are finished, you can write in your journal,” Mrs. Craft says. “It’s Friday, so you can do any creative writing you want.”

Jayland is writing a “chapter book” titled Hard Knock Chronicles. His protagonist is Tyson Rose, aspiring quarterback. Tyson moved from Tennessee to Texas and made the team. Not just that, but on the first day of high school, he got a girl’s number.

Along with a few other boys, Jayland reads his latest chapter aloud to the class, putting on different voices for each character’s dialogue. Would the boys do this with girls in the classroom? “Probably not,” Giani says.

Next up: Ms. Baxter’s math class and another test. “I just have to figure out how to do inequalities,” Giani mutters to himself. This class is small, 12 students. The boy who struggled with the test on The Giver arrives late and skims the math questions with a look of dismay.

Giani finishes with plenty of time to spare and leans back in his chair, looking nonchalant. He’s wearing slip-on loafers and black ankle socks with his uniform khakis and white shirt. Math is his favorite class. “You all knew this test was coming for two weeks,” Ms. Baxter says as other students struggle. The boy with freckles again leaves a test sheet almost entirely blank. When class is dismissed, he walks out last—in tears.

Giani hangs back in the hall. “You’ll be okay,” he says quietly to the crying boy.

A week later, the class reviews homework. Proportions. Ms. Baxter asks for volunteers to show how they solved the problems. The freckled boy raises his hand, and she calls on him.

“This is my first time writing on the board, y’all,” he says. And solves the problem correctly.

Photograph by Matt Moyer

Another Friday. Normally a quiet day of tests and art classes. Suddenly, there is a commotion in the hall, and Principal Birkett leads boys toward his office. Giani. His friend Jeremiah. Jayland. Half of the seventh grade.

The principal ushers boys in and out of his office. Soon, the only one left in the hallway is Giani. He sits at a school desk in front of the office door. On the wall opposite him is the bulletin board with photos of the “Eagles of the Month.” There’s Giani at the Capitol, shaking hands with state officials. There he is eating the congratulatory meal from Chick-fil-A. There he is posing with Mr. Miller.

Here’s what happened: Another incident with a substitute teacher. English class. The boys were working on questions about The Giver. Giani and Jeremiah got into an argument. Jeremiah shoved Giani; another boy grabbed Jeremiah to hold him back. Giani started to lift up a chair, but quickly set it down. Jeremiah stormed out into the hall, as Principal Birkett arrived and made all the boys write down what had happened. Take this job seriously, he said. You are all witnesses and this is serious business. Someone could get expelled.

Sitting out here, Giani is not sure what will happen next. He’s scared.

He is summoned into the office. He’s in there for a long time. When he comes out, his eyes are dry, his face composed. “I’m going back to class,” he says. Principal Birkett had called his mother. “She was happy that I controlled myself,” Giani says.

The day carries on. A/V class. Lunch. Science. Social studies. Mr. Moore teaches them to compose haiku; Giani writes about snakes and squirrels.

Final bell. It’s been a long week. Principal Birkett and Artesius Miller watch the students race around the grassy field in front of the school.

“This is middle school,” the principal says. “They are learning how to be responsible for themselves and for others.” He explains that he took statements from the boys in class and used them to make his decision. Jeremiah will be suspended for a day—out of school. Giani will have a day of in-school suspension. No one is getting expelled.

Whatever drama happens at school, “it’s a lot calmer than what’s out there,” says Miller, waving toward Upper Riverdale Road and the outside world.

Cars and trucks pull into the driveway. Students say goodbye, climb into backseats. On Monday morning, everyone will be back. And Principal Birkett will have much to say to them.

This article originally appeared in our January 2015 issue under the headline “Held to Account.”