There are times when Nancy Ann Grace dreads the darkness. The nightmares are especially vivid when the veteran Fulton County prosecutor literally takes her work to bed with her, snuggling up to the reports of murders, rapes and other violent crimes until she dozes off with the gruesome details of another horror coursing through her mind. Sometimes she must suffer through a bloodstained reenactment, rendered powerless as another innocent person is victimized. Other times she finds herself being pursued by a defendant, only to wake up drenched in sweat, her heart pounding.

There are times when Nancy Ann Grace dreads the darkness. The nightmares are especially vivid when the veteran Fulton County prosecutor literally takes her work to bed with her, snuggling up to the reports of murders, rapes and other violent crimes until she dozes off with the gruesome details of another horror coursing through her mind. Sometimes she must suffer through a bloodstained reenactment, rendered powerless as another innocent person is victimized. Other times she finds herself being pursued by a defendant, only to wake up drenched in sweat, her heart pounding.

“Sometimes I just can’t keep from bawling,” she says over lunch on a summer day in Buckhead, her long blonde hair falling over her gym shirt. “The stories just break my heart. How could they not break my heart? I don’t ever want to get to the point where they don’t break my heart.”

In a job in which callousness and detachment often are wielded like psychological shields against the incessant barrage of human tragedy, Atlanta’s most feared prosecutor is defined as much by her need to feel vulnerable as her determination to be strong. Grace, who has forged an undefeated record over almost a decade—including the 1994 murder conviction of Hastings Nature & Garden Center owner Weldon Wayne Carr—embraces her cases with a degree of emotional intimacy and intensity that blurs the line between prosecutor and victim.

“With Nancy, it’s always personal,” says Atlanta defense attorney Rene Rockwell, a long time friend. “Her victims are like members of her family, and her cases are like crusades.”

Although the petite Southern belle with the soft drawl endeavors to maintain a sugary disposition, her kinetic, workaholic existence is constantly awash in the pathos of those who have been victims. Working nights and most weekends, and rarely taking vacations, she pursues her cases with a missionary zeal while getting caught up in the details of all those shattered lives. Her daily life is replete with examples of her need to feel close to victims, such as the Tiffany pen that often dangles on a silk string around her neck. It was a gift from the family of murdered businessman Stephen Hynes; after the conviction in his 1983 slaying was overturned on appeal, Grace gained a second conviction, in 1994.

“We had a sense that Nancy truly understood what we were going through,” says Peggy Hynes, the victim’s sister. “We felt like she was fighting for us.”

She’s also fighting for herself.

Nothing demonstrates the bond between prosecutor and victim quite as powerfully as the gold band that Grace sometimes wears on her left hand. Sixteen years ago the only man she ever loved was to give her the band as a wedding ring. But Keith Griffin was murdered six months before they were to be wed, and as much as his death devastated her, it became a defining moment in Nancy Grace’s life, launching her into the emotionally charged existence of the victim as prosecutor.

“I don’t need anybody to tell me what it feels like to have someone special taken away,” she says.

Although success has earned her enemies in and out of the district attorney’s office, Grace’s vigilance and skill in pursuit of convictions have made her a popular expert legal commentator for the television networks and a rising star among the Atlanta legal establishment. Although powerful members of the local Republican Party tried to convince her to run for district attorney this year, Grace (who is a Democrat) insists she cannot imagine a job that would be as fulfilling as prosecuting violent criminals.

But even as her friends and relatives laud her success and her sense of purpose, they wonder how long Grace, 35, can continue to mask her broken heart with such a relentless devotion to her cases.

“I don’t think I could survive the trial work at her intensity level as long as she has,” says fellow assistant district attorney Rebecca Keel. “Sometimes I wonder why she wants to be Nancy Grace.”

The prosecutor always planned to teach college literature. Growing up in Macon, the youngest of Mary Elizabeth and Walter Malcolm Grace’s three children, she read voraciously from an early age, devouring the classics, especially Shakespeare. Her favorite book was To Kill a Mockingbird, but the story of the principled stand of Atticus Finch made her want to become a writer, not a lawyer. She enjoyed varsity cheerleading at Windsor Academy, where her bubbly personality and good looks made her popular, but she always found more satisfaction in analyzing the tragedies of Othello or Macbeth. Her mother, who was an accountant and now teaches piano, and her father, who worked for a railroad, always talked to her in terms of what she was going to be when she grew up. By the time she hit high school, there was never any doubt.

Then, early in her freshman year at Valdosta State she met Keith Griffin. The blue-eyed geology major was everything she wanted, and she was hopelessly devoted to him, in a way you can only be at that tender age. After spending the weekend with his fiancé and her family during the summer before their junior year, Griffin returned to work at a construction site in Madison. Around lunchtime he took the boss’s Jeep to buy soft drinks for the crew, and in what apparently was a case of mistaken identity by a disgruntled former employee, he was gunned down on his way back to the site. The shooter had a list of prior arrests.

Devastated, Grace dropped out of college and fell into a lengthy depression. For several months she lived with her sister in Philadelphia, unsure of how to pick up the pieces. “Nancy was so heartbroken, she really didn’t know how she was going to go on,” says her sister, Ginny.

With a suddenness that surprised her family and friends, she decided to go back to college and pursue a law degree. Keith’s death was like an epiphany. “There came a point where I knew I couldn’t just sit in a classroom and watch the world go by,” she says, “I had to see if I could make a difference.”

Making a difference meant prosecuting violent crimes, but after graduation from Mercer Law School, no district attorney’s office would hire her. After a year clerking for Federal Judge Allen Chancey and another two in the Atlanta regional office of the Federal Trade Commission, she got her big break when Fulton County District Attorney Lewis Slaton offered her a prosecutor’s position. “I felt like a bird set free,” she says.

More than empathy, the all-consuming dedication she employs on a daily basis appears to be a conscious attempt to fill the void left by her fiancé’s murder. Although she has dated many men in the years since Keith’s death, her personal life has taken a backseat to her career, and she’s never come close to marriage. Friends and family doubt that she will ever truly let go of him. “She says she’s gotten over Keith,” says her mother, who remains her closest confidant, “but it’s kind of obvious that she hasn’t.”

“I know I transfer all that about Keith in to my cases,” Grace concedes. “I loved him so much, and I don’t want to let go. But I don’t think it’s unhealthy. It gives me strength.”

In addition to being tormented by the murder, for many years Grace found herself wondering about Keith’s role in changing her life. She struggled with the concept of fate even as she tried to channel her anger into a productive career. “I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m here doing what I’m doing for a reason,” she says. “But does that mean Keith was just some sort of sacrifice? I can’t believe that.”

Every few moments Anton Germaine smith steals a glance in Nancy Grace’s direction, but only when her head is turned to the jury. Seated next to his lawyer inside Judge Alice Bonner’s courtroom, the accused serial rapist holds a ballpoint pen in his left hand, alternately clicking it open and shut.

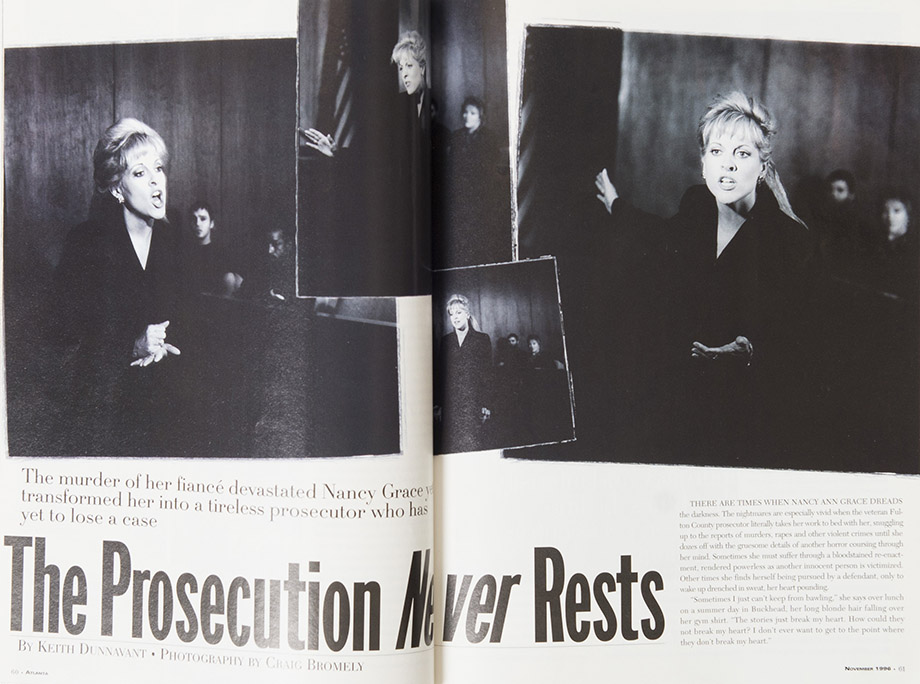

The prosecutor, dressed in a conservative white suit, stands before the jury box, making her opening argument, describing the brutal attacks as if to a friend. Using simple, declarative sentences, she tells them how the defendant allegedly broke into one woman’s house in the middle of the night and, after raping her and sodomizing her, forced her to read aloud from the Bible. Her voice rises to an indignant roar while informing the jury that the final attack was committed after the defendant had been arrested and released on bond.

Walking over to the defense table, she points toward the defendant with a pained expression. But he looks away, “This man,” she practically shouts, “is a savage.”

“A large part of my job is making an emotional connection with the jury,” she says later, after winning the conviction. “The technical evidence may prove guilt, but a lot of that stuff goes over the jury’s head.”

As Grace’s undefeated streak stretches toward 100 cases—she says she cannot confirm the precise number, but it is somewhere in the 80s—every defense attorney in town would give a month’s pay to beat her. Her combative ways and animated Southern belle style have won her few friends among defense attorneys, and many charge that her record is inflated because she drops any case that she could possibly lose. Her occasional flamboyance also rubs some the wrong way; such as the time she called a drug sniffing dog as a witness in a cocaine trafficking case.

Last year defense counsel Dennis Scheib caused a stir by filling a pretrial motion asking that Grace be prevented from wearing “inappropriate attire,” such as low-cut blouses and short skirts that show off her figure. Grace, who typically wears conservative suits and dresses to court, dismissed the motion as meaningless subterfuge. She won yet another murder conviction.

Although longtime district attorney Lewis Slaton, who is retiring this year, offers nothing but praise for his star litigator, many of his other attorneys privately express resentment of her. Some deride her as manipulative. Some chafe at the high profile she has gained in recent years, particularly since she became a commentator for NBC’s Today show, CNN and Court TV during the O.J. Simpson trial and now appears regularly on CNBC and ABC as well.

“It’s hard to do your job when you have to worry about your colleagues stabbing you in the back,” says her friend Rebecca Keel.

But not even her detractors can deny her work habits or her legal skills.

In addition to her gift for elocution in front of the jury—punctuated by carefully timed eye rolls and facial expressions that have become the bane of her opponents—Grace has succeeded because she has a keen understanding of trial strategy and because she prepares assiduously. Not content to stand on the investigations conducted by law enforcement agencies, she makes a point of interviewing all possible witnesses personally, sometimes trudging off to the worst sections of town during the middle of the night.

“She’s absolutely fearless,” says special agent Ernest Nesmith, an investigator for the district attorney’s office. “I try to keep her from going out to certain areas by herself, but she doesn’t always listen to me.”

Although her first case in the district attorney’s office was a minor shop lifting offense, Grace quickly gained her boss’s respect and moved up to major felony crimes—her third case was a murder. Three years after joining the department, in 1990, she was handed the case that would make—and nearly break—her career. Despite winning a conviction in the drug-related gangland slaying of three Red Oak Housing Project youths in southwest Fulton County, the strain of the extremely violent case caused her to consider leaving the law.

“It was so horrible,” she says, her voice falling to a whisper. “Three dead boys, drug dealers, that nobody cared about except our office. It was all I could do to stand up in court every day looking at the autopsy photos. I thought long and hard about quitting after that.”

Three years later she faced one of her most difficult challenges in a case that evoked memories of her own tragedy. In 1983, when Grace was in law school, Stephen Hynes and his fiancé, Catherine Moore, were toasting their engagement on the patio of his Buckhead home when an attempted robbery turned to homicide. When the decade-old conviction of Hynes’ murderer was overturned, Grace retraced enough evidence to gain a second conviction. She won, although now the co-defendant’ s case, which she did not originally try, has also been kicked back on appeal.

The case against Weldon Wayne Carr, the millionaire owner of Hastings Nature & Garden Center, loomed as the biggest and toughest of Grace ‘s career. In April 1993 Grace was driving to work early one morning when she heard the news that Patricia Carr had died after a fire in her house. “I knew right then,” she says. “It was just too suspicious.”

The state alleged that Carr had burned his own house to the ground in order to murder his wife, but all it had was circumstantial evidence. Proceeding on a hunch, Grace obtained a search warrant for Carr’s safe deposit box and warehouse and found numerous items—including cherished family photographs and college annuals—that she was able to use to suggest premeditation. The state also was able to prove that Carr had surreptitiously taped telephone conversations between his wife and her lover, suggesting a motive for the crime.

But the defining moment of the trial resulted from Grace’s keen sense of theatrics.

Grace placed the Carr’s clergyman on the stand to testify about having been called to the defendant’s jail cell. She asked the preacher, “That whole time you were there with the defendant, did he ever ask you to pray for his dead wife?”

“No,” the minister replied amid a flurry of defense objections.

“I saw this look of disbelief from these four ladies on the first row [of the jury box],” Grace says. “I knew that was it. I had him.”

During the trial Grace kept the cassette tapes that Carr made of his wife and her lover in her glove compartment. Sometimes, when she was driving to Macon to see her parents or stuck in traffic on the Perimeter, she listened to the tapes and felt sad for Pat Carr.

Last year a prominent family from out of state approached Grace about taking a leave of absence from her prosecutor’s job to defend a young woman accused of murder.

Money was no object, and she could have earned more with one case than she takes home from the district attorney’s office in two or three years. But she said no. “I don’t think Nancy would be happy as a defense attorney,” says her friend Martha Glisson, “unless she could pick and choose her cases.”

About the same time Grace placed her name in consideration for a Fulton County superior judgeship, and although she made the short-list of candidates, she does not seem excited about the prospect of watching from the bench.

Although she was flattered by the overtures of Republican operatives about running for district attorney, she concluded, after a sleepless night, that she has no aspirations in politics.

The law classes she teaches at Georgia State and her frequent television appearances satisfy urges, but neither represents a crusade.

“I know there will come a time when I walk away from this life,” she says. “There have been times when I’ve felt I’ve had enough, but I’ve always gotten over it. One of these days it’ll be time, and whatever I do next probably won’t have as much control over my life.”

Although she has put off marriage and children while she pursues her crusade, she often thinks about what she is missing. “I wish she would settle down,” her mother says. “Her career is so important to her, but sometimes I worry that she’s going to wake up and feel like she’s given her whole life to prosecuting.”

Even as Grace wades through the muck of one horrific crime after another, she continues to struggle with her own hurt that will never heal. But she is making progress.

Several years ago Valdosta State invited her to help dedicate a baseball field in honor of Keith, but she could not bear to attend. The wound was too fresh. When the college called earlier this year and asked if she would like to participate in a reunion in her fiancé’s honor, she struggled with the decision for weeks before taking an important step toward her own tentative recovery.

“I feel like it’s time,” she says. “I think I’m strong enough now.”

Keith Dunnavant is an Atlanta freelance writer and author of Coach: The Life of Paul “Bear” Bryant, published by Simon & Schuster.

This article originally appeared in our November 1996 issue.