TagsAtlanta BeltLineAtlanta BeltLine Eastside TrailAtlanta BeltLine Southside TrailAtlanta BeltLine Westside TrailBellwood QuarrydevelopmentEastside TrailRyan GravelSouthside TrailWestside Reservoir ParkWestside Trail

Home The future of the Atlanta BeltLine: 4 benchmarks to watch for

Where does the Atlanta BeltLine go from here?

The future of the Atlanta BeltLine: 4 benchmarks to watch for

Photograph courtesy of City of Atlanta Department of Watershed Management

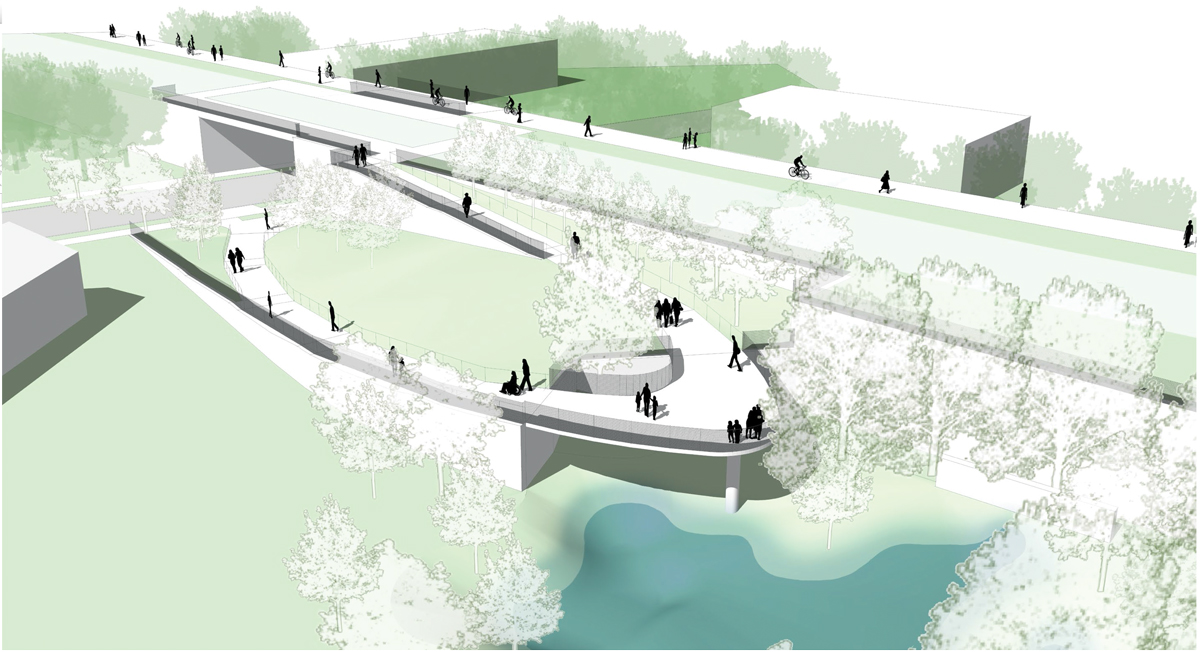

Westside Reservoir Park

When: 2019 (first phase)

Just off the Atlanta BeltLine’s proposed Northside Trail, the defunct 350-acre Bellwood Quarry is in the early stages of a more than 10-year transformation to become Westside Reservoir Park, the city’s largest greenspace. For the past year a tunnel-boring machine nicknamed Driller Mike (after the Atlanta rapper) has chewed a path from the pit to the water treatment plant off Howell Mill Road and will eventually hit the Chattahoochee River. Once complete, water will flow through the new tunnel and fill the 400-foot-deep hole, creating a 2.4-billion-gallon emergency drinking water reservoir and the crown jewel of the park. There’s no price tag just yet, but observers expect the greenspace—which will feature an amphitheater, playing fields, and links to the planned Proctor Creek Greenway Trail—to spark redevelopment of this largely industrial area. First, baby steps: City officials are fielding proposals to create an entrance off Johnson Road and trails to Proctor Creek and a “grand overlook” offering views of the reservoir and skyline.

Southside Trail

When: Early 2020s

The four-mile stretch of the BeltLine between Glenwood Park and southwest Atlanta’s Adair Park won’t just be the project’s longest segment, but also its most visually striking, says Lee Harrop, a program director at Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. “The topography is so dramatic,” he says. “The Southside Trail is where the railroad cut through topography to create a straight line. You’ll have some dramatic skyline views. The engineer in me is kind of geeking out.” Up until two or three years ago, freight rail traveled along the tracks still owned by CSX, so the area is not far removed from its railroad roots. The path will travel over five bridges, including a 70-feet-high red trestle and through one of the BeltLine’s longest tunnels. ABI is now halfway through the design, which will have to be approved by state transportation officials, and is in talks with CSX to purchase the section. Next year they will finish the plan and, if they can acquire the tracks, prepare to start work in 2020.

Photograph courtesy of the BeltLine

Northwest Segment

When: Before 2030

Even the BeltLine’s die-hard supporters scratch their heads about how the segment between Washington Park and Lindbergh will become a reality. Unlike other parts of the BeltLine, CSX freight trains still rumble along this corridor, and the rail company has never signaled it will abandon the route. BeltLine transit might be able to run alongside the tracks. (Charlotte, North Carolina, is studying such a system.) For the bike path, ABI officials plan to turn an overgrown set of tracks they’ve dubbed the “Kudzu Line” into a bike trail that starts near Washington Park, close to the future Westside Reservoir Park. The trail would then travel near the new Bacchanalia and potentially through the city’s water treatment plant before connecting to the Northside Trail in Buckhead and snaking to Lindbergh. Once ABI finishes the Southside Trail and extends the Eastside Trail past Ansley Golf Club, bicyclists will be able to pedal 16 miles around the city.

Transit

When: TBD

When Ryan Gravel first envisioned what would become the BeltLine, the project did not emphasize public art, affordable housing, parks, or even bike trails; he just wanted to turn unused railroad tracks circling Atlanta’s urban core into a loop of light rail that would link 45 neighborhoods. But nearly 20 years after Gravel published his graduate thesis, no streetcars are running, and skeptics doubt they ever will. Some BeltLine observers privately pondered if the project should simply widen the bike trail. But Gravel says it’s vital: “Transit is the thing that makes the BeltLine for everyone. Walking, biking, and other examples of people-powered mobility are wonderful forms of transportation, but they don’t work for everyone at every time of day or in every season.” In November 2016 Atlanta voters overwhelmingly approved a sales tax that would generate as much as $2.5 billion for new transit in the city, including BeltLine routes, most of which include crosstown spurs connecting to MARTA. Though the next mayor will play a large role in deciding which routes get the first shot at funding, federal officials will only help pay for lines they think will be most successful. Two areas considered primed for new transit: the more-crowded Eastside Trail and the Westside Trail, which is home to more people who are dependent on transit. —Thomas Wheatley

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)