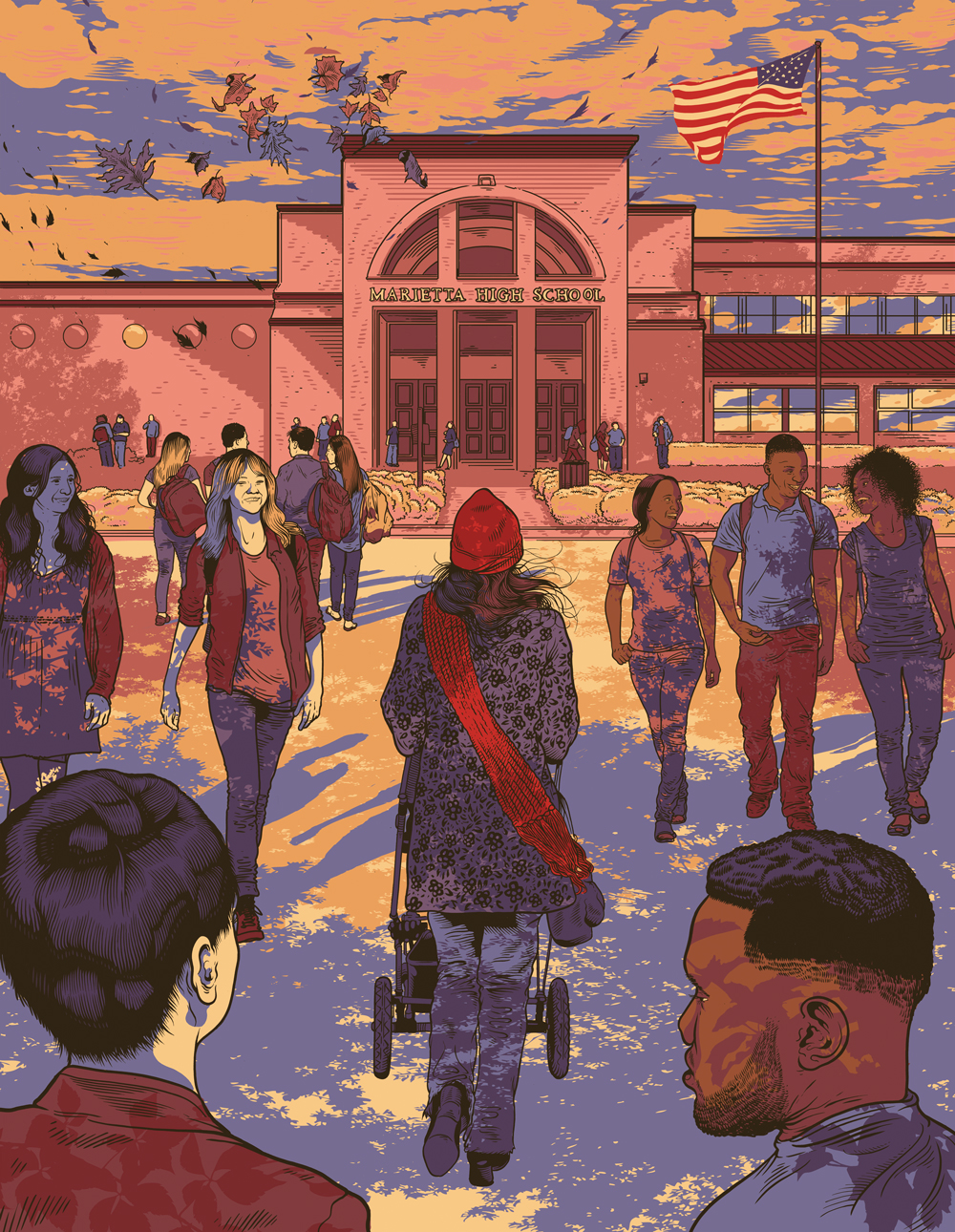

Illustration by TIm McDonagh

By the 1980s, desegregation at Marietta High School was a success. Its students mirrored the city as a whole—roughly 25 percent black, 70 percent white, 5 percent other. Thirty years later, the mix is 25 percent Latino, 49 percent black, and 21 percent white. Like many school systems nationally, the Marietta district is resegregating.

In 1967, the city of Marietta closed Lemon Street High School, sending its students—all of them black—to Marietta High. And so began another Georgia city’s halting steps toward school desegregation, 13 years after Brown v. Board of Education. That first year, winning the school’s first (and still only) state football championship helped unite the blended community. By the 1980s, enrollment mirrored the city as a whole—roughly 25 percent black, 70 percent white, and a few Latino and Asian students. Marietta seemed the embodiment of the Supreme Court’s call for integration of public schools.

But beginning in the 1990s, as Cobb County’s demographics shifted, so too did the racial makeup at MHS. By 2012, the student body was 25 percent Latino, 49 percent black, and 21 percent white—even though half of the city identified as white. Where did the white students go? Through doors opened by “school choice,” they fled for magnet, county, parochial, and private schools.

Some of them were Ruth Yow’s classmates at the Walker School, a nearby independent school that is Marietta’s longtime rival. Years later, while earning her doctorate in American Studies at Yale, Yow took a closer look at MHS’s evolution. That project grew into a book just released by Harvard University Press, Students of the Dream: Resegregation in a Southern City. Weaving together oral histories and research, Yow explores Marietta High’s relapse as a case study of national trends—and calls for a new era of integration.

• • •

Excerpt from Students of the Dream: Resegregation in a Southern City

Daniella Sanchez spends her days in a leasing office overlooking the community garden in the courtyard of Liberty Pointe Apartments. Bilingual, charismatic, and patient, Daniella is terrific at her job managing Liberty Pointe, one of those rare “good” jobs in tough economic times: kind coworkers, reasonable hours, and decent benefits. When we met, she was smartly dressed and sporting delicate gold jewelry; the two tattoos peeking out from under her sleeve were the only hint that she was not to the manner born. In fact, to what Daniella was born is at the heart of her story. Her experiences as an undocumented student on the economic margins in Marietta are a testament to the powerful determination of such students who face a system in which persecution is a matter of course.

Without papers, Daniella and her mother came to the United States from Mexico City in 2003. They settled in Cobb County, near—but not in—the city of Marietta. An excellent student of English, Daniella was moved in and out of Cobb’s transitional academy for international students in just a few months, ready to be integrated into the school system at large. After a short stint at a Cobb County high school, Daniella was anxious to move on again: boisterous, violent students ran the show, intimidating the resource officers and fostering a tense, uncomfortable atmosphere. She found that Marietta High was nothing like that. “It was very nice!” she recalled. “Everyone was doing awesome.” After enrolling, Daniella joined Marietta High’s JROTC (Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps) program and loved it. As she gathered from her peers, JROTC would pay for college. From there, she would go to medical school and train to be an obstetrician-gynecologist. “I had A’s, A’s, A’s,” she said, recalling how motivated she’d been in the middle of high school to earn a high grade point average and excel in JROTC. “But of course,” she told me with a sheepish smile, “there was a boy.” After Daniella got pregnant, she attempted to stay in school—to change nothing, to let no one know—but word got around to her teachers, and eventually, she confessed to a guidance counselor who was sympathetic, offering to get her a doctor’s appointment and investigate child care options. I should have done better, thought Daniella, but things could still turn out well. She could still go to college, still serve in the Navy, still have the life that living in the United States promised a smart, hard-working student.

Cobb County authorities, armed with the power of both federal provisions and state law to identify and detain the undocumented, were ready for Daniella’s family and the thousands like them. Two months before Daniella gave birth, her mother was pulled over by county police for a minor traffic offense. It landed Ms. Sanchez in jail because she had been driving without a license. For the undocumented, citizenship is mostly about the many “papers” the paperless lack: work permits, business and home loans, Medicare and Medicaid, Section 8 vouchers, food stamps, Pell grants, state scholarships, unemployment, retirement, workers’ compensation. . . .Needless to say, when asked to “show her papers,” Ms. Sanchez had none. A $5,000 bond was posted, but Daniella was told that even if she and her sister devastated their savings and paid it, their mother would still be transferred to ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and deported. The daughters did not attempt to get a lawyer, and like 94 percent of detained immigrants without legal representation, Ms. Sanchez was deported.

The “deportation machine” tore another family asunder. Left alone with their children—Daniella’s baby and her sister’s kids—in a house they couldn’t pay for without their mother’s income, Daniella and her older sister were forced back to the trailer park where they’d lived upon first arriving in Georgia. Daniella had to leave Marietta High; she was once again districted for Cobb County schools. She, her sister, and their children struggled to stay afloat in Cobb, and Daniella forged ahead toward graduation from her new high school. It was precarious and difficult, but they were doing it, until, that is, the next encounter with Cobb’s law enforcement. “My sister,” said Daniella with a sad smile, “she was very good with me—but not so good with the police.” A cocaine user, a lover of dance clubs, an instigator of fights, and a reckless driver, Daniella’s sister eventually got into real trouble. Even though she gave a false name—associated fortuitously with a documented immigrant—and her correct address to an arresting officer (“A correct address with a fake name?” exclaimed Daniella. “Who would do that?”), she was, astonishingly, released on bail. After running her fingerprints the next day, however, police eventually identified her as an undocumented immigrant with a previous charge. Around 1 a.m. a couple of nights later, officers came to the trailer park, looking for the Sanchez’s unit. The last time Daniella saw her sister, she was disappearing around the back of their trailer with “her keys and her stuff,” as Cobb County police rapped on neighbors’ doors seeking her.

What is the recourse for a teenager whose family members are fugitives of a state intent on leaving her with nothing and no one? At 17, Daniella was alone with her baby. Out of options, she confided in the social worker who ran the class for teen mothers in which she was enrolled at her new high school. “I told her, ‘I’m about to lose my home, and I have a kid, and I don’t have no family.’” With the help of that social worker, a volunteer with the teen mothers program, and a sympathetic immigration officer, Daniella obtained a work authorization. Soon after graduating, she got her “first real job” working in the leasing office of an apartment complex (“They needed someone bilingual!”) and eventually an even better job at Liberty Pointe.

What is the recourse for a teenager whose family members are fugitives of a state intent on leaving her with nothing and no one? At 17, Daniella was alone with her baby. Out of options, she confided in the social worker who ran the class for teen mothers in which she was enrolled at her new high school. “I told her, ‘I’m about to lose my home, and I have a kid, and I don’t have no family.’” With the help of that social worker, a volunteer with the teen mothers program, and a sympathetic immigration officer, Daniella obtained a work authorization. Soon after graduating, she got her “first real job” working in the leasing office of an apartment complex (“They needed someone bilingual!”) and eventually an even better job at Liberty Pointe.

Not feeling safe in the immigrant community is less about the fear of a mugging or car theft than the knowledge that a missing tail light may mean the end of life in the land of opportunity. Daniella’s tale is unusual only in its ending—the stability that she crafted out of chaos.

• • •

Instead of opportunity, America has become the land of loss, loneliness, and rightlessness. And instead of a bridge to the future for immigrant students, high school has been rendered an island from which the bustling and beautiful mainland is ever receding. Daniella Sanchez learned about all that—watching what was hoped for slip away and carrying the loneliness, heavy as a sleeping child in her arms. Along with her own tenacity, serendipitous encounters with kind adults may have saved Daniella’s life. However, her experiences point to the structural truth that for many immigrant students in Marietta and across the United States, the nightmare of being deported remains more real than the dream of becoming an OB-GYN.

Not feeling safe in the immigrant community is less about the fear of a mugging or car theft than the knowledge that a missing tail light may mean the end of life in the land of opportunity.

In negotiating the choppy waters of change, Latino students integrating Marietta High have faced some of the same challenges as the black students of the mid-’60s. Many of the same arenas of interaction—the field, the classroom, clubs, and the community at large—are the sites where black students, and now Latino students, make the transition from members of the student body to its leaders and activists. The second-class citizenship endured by black citizens (and by Mexican Americans in places like Texas and California) during the Jim Crow era has some resonances with the “underclass” to which undocumented youth are being relegated. Yet after the Brown v. Board decision in 1954, the exclusion of black children from white schools and any group, team, or affiliation thereof had no legal foundations.

• • •

Conversely, contemporary immigration law delineates sharp distinctions, not based in skin color but based on a difference you can’t usually see: “legal” and “illegal.” “They [feel] they are not supposed to talk about [not having papers],” 2011 MHS alumna Amy Rocha, who is herself undocumented, told me. “They are just . . . shadows.” In Rocha’s interpretation, the undocumented student’s difference is paradoxical; it is invisible and yet it makes them invisible, too, at least to the administrators and teachers whose support those students need most. For the undocumented students at Marietta High—and the principal estimates that they make up 90 percent of the Latino student population—citizenship finds its social salience in the quotidian details of studenthood: who drives to school and who can’t, who takes an internship and who doesn’t even apply.

The Daniellas of Marietta’s schools have sought solid ground to stand on but have found little institutional support for their struggles. Like its high-poverty peers across the country, Marietta High School is a shock absorber of rising inequality in the city: It faces increasing expectations of and demands on teachers, students, and school leadership as well as plummeting levels of state and federal funding. In the 2000s, MHS has seen ever higher enrollments of low-income Latino students and falling numbers of affluent students and has teetered on the edge of racial and socioeconomic resegregation. There is, for the most part, no burgeoning malice toward or conspiracy against poor and undocumented students at the high school; on the contrary, MHS is staffed by committed teachers and administrators who want all students to flourish. However, the education reform agenda in Marietta is a neoliberal one, and the programs promoted by the school board are not designed to open doors for poor students of color or students without documents.

• • •

Q&A with author Ruth Carbonette Yow

Illustration by TIm McDonagh

Why did you decide to study Marietta High School?

I grew up in Cobb County and was interested in studying public education, but I went to the Walker School, which is private. I never rode a school bus. I didn’t go to class with people of different socioeconomic levels, to say nothing of race. When I went over to my Walker friends’ houses in Marietta, we could hear the sounds of the football game. I thought: Whoa, that must be what a real high school is like. I really fetishized it as an authentic high school culture. So Marietta was sort of in the back of my mind from the time I was in ninth grade back in 1997. I wanted to do my dissertation research where I wouldn’t be a total outsider but where I would have a partial outsiderness—having observed public school culture from this sort of wistful distance.

Is the type of resegregation that you observed at Marietta happening nationally?

Yes, it has happened nationally over the last two decades. The average white student now attends a school where 77 percent of students are white, whereas black or Latino students go to schools where about half of their classmates match their demographics. These numbers are disproportionate to the populations served by public schools. Perhaps predictably, it’s happening in the places where Latino immigration is highest: Texas, California, New Jersey, New York, and the deep South. What is especially sad, though, is that in a lot of those other places, there was never any real integration because segregation had not been mandated by law. There were no discriminatory laws for courts to challenge. But in the South, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) had this massive impact. By the mid-’80s, almost half of Southern black children were in well-integrated schools—versus only 27 percent in 2005. So today’s resegregation is happening in places that had once desegregated successfully and achieved some kind of meaningful racial balance.

But didn’t the Supreme Court make segregation illegal?

Between 1964 and 1974, Supreme Court decisions facilitated integration by legitimizing measures like cross-district busing. In Green v. School Board of New Kent County (1968), the language was weirdly beautiful. They ruled it was their job to remove segregation “root and branch.” So, that’s your mandate. In the late ’60s and the early ’70s, districts were innovative in creating busing and other kinds of plans that, in many cases, didn’t make parents very happy but were really fabulously successful at bringing schools into racial balance. By the 2000s, the tide had turned, and court decisions no longer supported desegregation measures like busing or school choice policies that favor minorities. Residential segregation and outmigration began segregating the schools once again, but this time there was no legal recourse.

You make the point that kids who were integrating schools in the ’60s basically had the law on their side, but for today’s students, the reverse is actually true.

Yes, many of today’s integrators are Latino. Tough immigration policies have, in many cases, made fugitives of undocumented community members and poisoned the relationship between students and their schools.

In the Marietta school district, all students go to the same high school, so busing wasn’t an issue. Why is their student population changing now?

Demographics have really spurred Marietta’s resegregation. And there are lots of choices for families today, even if they can’t afford to send their kids to Westminster. It’s not just parochial schools but all kinds of hybrid schools, Christian schools, magnet schools. It’s a huge spectrum.

We think of “school choice” as a new idea, but you point out that it’s really an old idea that was struck down by the courts in the ’60s. Why is it being resurrected now?

To mitigate the effect of Brown, Marietta and other districts across the South offered school choice, which basically put the onus on black parents to apply for their children to go to all-white schools. The burden was entirely on black pupils, because no white person was going to opt to attend an underfunded black school. So, it spurred basically no integration. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent rulings said schools could lose federal funding if they didn’t implement effective integration measures. So, freedom of choice was essentially invalidated in the ’60s.

So why is school choice legal now?

Today, school choice is basically a free-market technique to open up more options to parents regardless of race. It’s ostensibly unrelated to the degree that your school is integrated or not. Those plans are a mixed bag because, in many cases, they speed resegregation as parents make choices that are motivated by race, though not in any spoken or traceable way.

However, as you point out, today’s parents are often themselves products of well-integrated, late 20th-century schools, who value diversity. But in the end their primary goal is academic opportunity for their children. They’re not running away from a racial mix like people did a few generations back, but they may be running towards high test scores.

For sure, if we imagine that the only reason parents choose schools is race or class, then we are ignoring a host of other factors. Parents don’t want to refuse an opportunity for their child. Parents would say to me, “I loved Marietta High so much. It made me who I am.” Then, in the next breath, they would say, “Public schools are so messed up. We ought to privatize the whole lot.” That’s a quote from a Marietta High alum.

You note that Marietta was an early adopter of the prestigious International Baccalaureate program, which is seen as a way to attract and retain high-performing students. Has that created opportunities for students?

IB is a program in which students are encouraged to think critically about differences and culture and politics, and they’re encouraged to have a really global, servant-leader mindset. So, for the IB program to be mostly white at a school with an international population like Marietta’s is heartbreaking. It’s a real contradiction. [Yow notes that, of 80 2011 Latino grads (representing a 39.1 percent graduation rate), fewer than 5 percent graduated full IB. However, MHS IB enrollment—with 47 percent white, 28 percent black, 18 percent Latino, 6 percent Asian, and 1 percent other races in 2012—is actually more diverse than national IB averages of 56 percent white, 7 percent black, 9 percent Latino, 15 percent Asian, and 13 percent other races in 2011.]

So what are the solutions? I assume you’re not calling for a return to busing, or are you?

I am not opposed to busing. But as you pointed out, that is not the solution for Marietta. For me, the answer has to be community support. What [former] Principal Leigh Colburn said once at commencement was so powerful: “Every kid who walks across the stage at graduation will be a member of our community, and every kid who doesn’t will also be a member of our community.” In 2013, Colburn launched a program called Graduate Marietta, where public-private partnerships help schools and students cope with problems like homelessness, deportation, child care, and depression—issues that go way beyond academics.

The city needs to grapple with its identity. It is no longer the Marietta that it was 20 years ago. It’s not even the Marietta that it was five years ago. Stakeholders need to think about educational equity and view kids of color as engines of positive change.

Ruth Carbonette Yow, PhD, is a Service Learning and Partnerships Specialist at Georgia Tech’s Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain.

Excerpt from Students of the Dream: Resegregation in a Southern City by Ruth Carbonette Yow, published by Harvard University Press, $39.95. Copyright © 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

This article originally appeared in our December 2017 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)