An Adairsville friend warned us before church. “See Barnsley’s daffodils. This week.” They were about to close public access to the northwest Georgia estate during development. We headed for the car as soon as I molted choir robe and collar. We didn’t even stop for lunch. Spring had been uneven. Sunday was righteous. When we parked we shed extra layers, grabbed sunhats.

An Adairsville friend warned us before church. “See Barnsley’s daffodils. This week.” They were about to close public access to the northwest Georgia estate during development. We headed for the car as soon as I molted choir robe and collar. We didn’t even stop for lunch. Spring had been uneven. Sunday was righteous. When we parked we shed extra layers, grabbed sunhats.

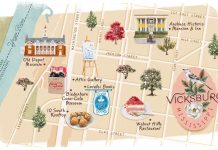

Woodlands, as we called Barnsley, had long been wilderness, with its battered mansion and broken heart. I grew up on the legends. Highway 41—two lanes before progress and interstate—ran right past. My earliest impression was kudzu wastelands and golden confetti. Thousands of acres of daffodils. A ditch away. Some came to picnic, some cut flowers for weddings, for welcome—or farewell—to soldiers returning from World War II.

I came along later, but I heard about it. Our car slowed, but never stopped. My father had seen Europe in ruins; he did not want to see Woodlands, but he slowed for the daffodils, going and coming.

Now here we were in long church skirts and sensible shoes, just in case. “Like the Amish ladies’ softball team,” Mama said. She regretted sensible shoes. Paths clear, tidied. Puddles shrinking in the heat. We were glad for hats. No leaves—no shade—and fierce sun. Ahead of us shimmered the broken dreams of Godfrey Barnsley. The prince had dreams too: lodge, cottages, golf, tennis, horses, spa, restaurants, gun sports, amenities. And a romantic avenue of roses, arbor hoops arching over the wide boulevard with old roses starting young. “We’ll come back,” my mother promised.

From the perimeter, we gazed into the estate’s formal heart, where the hedged fountain awaited healing. We had not come for ruins. We breathed in the drowsy hint of scent from the flowers. Way off, a few other lookers. Strolling. On my left, along that lower terrace, a man in a brisk hurry. We were not in his way or on his path. My mother also glanced. A tall man in European tweeds. In a flash, who it was electrified the afternoon.

Don’t let her curtsy, I prayed.

Some red-blooded American women go goosey when they see Queen Elizabeth on TV.

Here came Prince Hubertus Fugger, our host of golden daffodils, striding along in country tweeds, hands clasped behind him. He was covering ground, his countenance purposeful with unreadable thoughts. Not trespassers, but were we totally welcome?

After all, it was his estate. Should we about-face and walk? Too late. He was abreast. We “wouldn’t notice” him. His call.

He paused, tilting his head to see under the brims of our straw lids. Mama’s pink dress matched the color of her hat and its rose. Temp had to be in the eighties. A stinging hot day. All around us daffodils, nodding.

That is what my eighty-something mother did, as well. She met his glance then slightly tipped her hat brim down by lowering and raising her chin, a half-inch nod. Her back remained straight. Her shoulders squared, skirt-pleats knife-sharp, unbent.

“We are enjoying your gardens,” she said.

He spoke clear perfect English, choosing the exact word. “I am enjoying your charming . . . bonnets.” Facing us, he brought his heels together, no click but crisply military. Gravely, he bowed. And with a slight twinkle, strode on.

Mary Hood, an inductee into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame, is the author of four books, including How Far She Went (winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction) and A Clear View of the Southern Sky. She lives in Commerce, Georgia.