Portrait: Courtesy of Elizabeth Long, office of Mary Matalin.

She’s a take-no-prisoners Republican who served in both Bush administrations. He’s the “Ragin’ Cajun” Democrat who helped Bill Clinton get elected president. Mary Matalin, sixty-one, and James Carville, seventy, have three things in common: their college-age daughters—Matty and Emma—and their hometown, New Orleans. Turns out, that’s enough.

As chronicled in their New York Times bestseller, Love & War, Matalin and Carville have made a peaceful life in the Big Easy, where they’ve lived since 2008. He spends his days at Tulane University, where he teaches political science. She lectures at Loyola University and helms a nationally syndicated radio show. After work, they meet for drinks at Clancy’s in Uptown, the neighborhood where they live. They don’t bicker. Really. “New Orleans is the one place we’re in constant agreement,” Matalin says.

For Carville, leaving Washington for Louisiana was a homecoming. He grew up an hour northwest in Carville, a town named after his grandfather. His mother, a Cajun of Acadian descent, spoke French at home. “My blood’s not red or blue—it’s brown,” he says. Young Carville often traveled to New Orleans, especially during his teens, “to get drunk and stupid in the French Quarter.” To him, it was the greatest city imaginable.

Matalin, meanwhile, was raised in Chicago and didn’t set foot in Louisiana until a political event brought her to New Orleans in the early eighties. She was instantly enchanted by the thickness of the air, the tolling of the church bells, the saxophonists playing in the streets. When she and Carville married in 1993, she insisted they hold their wedding in New Orleans.

As much as they both loved the Crescent City, their jobs kept them tethered to Washington, D.C. But Carville says he always knew he’d go back—he just wasn’t sure when. “Look, I never wanted to be hanging around politics in my seventies,” he says. Then Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, and the timing became clear. Both he and Matalin wanted to move to the city they loved most in the world, and they wanted to get there before, God forbid, the town and its culture faded away. To hell with Washington: They were ready to go.

When they announced their decision, the political world howled. Surely Carville had intentions of running for governor. Or perhaps he and Matalin were trying to reinvent themselves as humanitarians. Carville just laughs. Today, when his friends from Washington visit, they see his mansion on Palmer Avenue, the riverside park where he jogs every day, and the world-class university where he walks to teach. “They’re like, damn, I didn’t know it was like this—I’d have come with you!” Carville says.

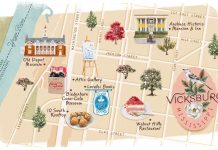

And indeed, his and Matalin’s life in New Orleans is enviable. Matalin fills their home with furniture she finds at Kevin Stone Antiques & Interiors (“Kevin has the best stuff for half the price you’ll spend on Royal Street”); meets her family for dinner at Chef Justin Devillier’s La Petite Grocery (“Justin is just wonderful”); and takes in jazz shows at Irvin Mayfield’s Jazz Playhouse (“Irvin wants to restore and maintain the culture and heritage of the only indigenous music in the United States, which is New Orleans music”). Tuesday evenings, she never misses mass at St. Stephen; since moving to New Orleans, with its saint-named streets and more than forty Catholic churches, she has converted to Catholicism.

Carville appreciates the city’s spiritual side, but what interests him most is its culinary one. He’s crazy about the red beans and rice at Katie’s, and swears they’re best on Tuesdays, when they’re a day old. He likes the oysters at Pascal’s Manale, the po’boys at Mother’s, and the shrimp remoulade at R & O’s. Sunday nights, he watches football and eats osso buco at Vincent’s, because, as he says matter-of- factly, “Cajuns eat Italian on Sundays.”

As Matalin and Carville look to the future, they say they want it to revolve less around politics and more around their passions. Matalin is an advocate for Women of the Storm, a group of Louisiana women who support the state’s recovery from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. And both Matalin and Carville are on the executive committee for New Orleans’ tricentennial celebration in 2018. Their goal is both clear and lofty: They want to show the world that New Orleans isn’t just back—it’s better than ever. “We’ve had more golden eras than hurricanes here,” Carville says. “But I really do think right now we’re in a true golden era.”

And, perhaps, so too are he and his wife.