visitBatonRouge.com

In 1699, French adventurer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville sailed up the Mississippi with a team of explorers. Eighty miles northwest of New Orleans, they spotted a cypress pole staked on a hill, stained red with blood, and adorned with fish bones and animal heads. It was a boundary marker between Native American tribes, and its warning was clear: Cross this line, and you will die. D’Iberville named the place Baton Rouge, French for “red stick.”

bigstock.com

Today, strolling the riverfront promenade in downtown Baton Rouge, you could easily consign the city’s forbidding origins to history. Old-fashioned steamboats chug along, bright red paddlewheels churning up the water. Sidewalk fountains whoosh, fall silent, then bubble back to life. Mothers with children, joggers with headphones, and professionals with briefcases breeze by.

And that’s the big story: the fact that as Baton Rouge turns 200, people are coming into downtown again—and not necessarily because they have business in the capitol or at nearby Louisiana State University. In 2001, there were no hotels downtown; now there are five, with a sixth—the upscale Watermark Baton Rouge—opening this fall. New restaurants like retro Jolie Pearl Oyster Bar consistently attract crowds. There’s even a gourmet market, Matherne’s, selling prepared foods and wine in the bones of a historic bank. When Matherne’s opened last year, it was the first time downtown had been served by anything approaching a full-service grocery store in fifty years.

Local historian John Sykes says the transformation reflects the city’s can-do spirit. Before he moved to Baton Rouge from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in 1996, “I was told the best thing about Baton Rouge is it’s forty-five minutes from New Orleans,” he says with a laugh. Today he begs to differ. “I’ve found that the people here have a distinct joie de vivre. They believe in Baton Rouge.”

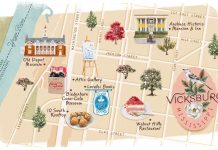

Baton Rouge Downtown Development District

Sykes serves as executive director of Magnolia Mound Plantation, a French Creole home built in 1791. The parish’s parks and recreation commission purchased the aging property in 1966 and set to work on a nine-year renovation, sending a clear signal that the region was committed to preserving its past. If you walk the home’s original cypress floors and examine its interior, you’ll notice French influences in everything from the imported toile wallpaper to the en suite floor plan. When the home was constructed, Baton Rouge was the westernmost city in West Florida, a territory formed by the British in 1763 and later captured by Spain. But the city’s French roots ran deep (France controlled the city for nearly half a century before ceding it to Britain), and most citizens held fast to their French identity.

In 1803, the United States finalized the Louisiana Purchase, but Baton Rouge and the rest of Spanish-controlled West Florida weren’t part of the deal. Cut off from their New Orleans neighbors and unhappy with Spanish rule, a group of West Florida residents launched a revolution in 1810, establishing a new nation—the Republic of West Florida—headquartered in Baton Rouge. The whole thing lasted ninety days, ending when the United States claimed the defenseless territory for itself. Baton Rouge became a part of Louisiana, incorporating in 1817; in 1849, it was named the state capital. Not because it was the biggest city or the most influential, but because state lawmakers determined that the capital should be at least sixty miles from New Orleans and its numerous “distractions.”

VisitBatonRouge.com

In 1852, esteemed architect James H. Dakin unveiled Baton Rouge’s state capitol building, a Gothic Revival fortress Mark Twain famously called a “little sham castle.” Nearly destroyed by fire during the Civil War, it was rebuilt by William A. Freret in 1882. (Today it houses a terrific museum showcasing Louisiana’s colorful political history.)

But this capitol was nothing compared to the one Governor Huey Long spearheaded in 1930. A thirty-four-story tower, it remains the tallest capitol building in the United States. Ride two successive elevators to the twenty-seventh-floor observation deck, and you’ll spot Long’s gravesite in the gardens below, marked by a twelve-foot bronze statue of the larger-than-life politician. He was assassinated in 1935 on the capitol’s ground floor; you can still see the bullet hole in the wall.

VisitBatonRouge.com

Baton Rouge’s role as the state capital has certainly brought it plenty of attention over the decades, but the city’s identity has also been shaped by Louisiana State University. Located five miles southwest of downtown, LSU draws hundreds of thousands to its oak-shaded campus and deafening Tiger Stadium. Students continue to pack Louie’s, a twenty-four-hour diner next to campus, for the seafood omelets and Cajun hash browns for which the place has been known since 1941. Longtime chef Marcus “Frenchie” Cox, a graying man with a bandana tied around his head, says he’s seen Baton Rouge change a lot in recent years. More people, he says. More diversity. He likes the energy these days, and he even enjoys trying some of the popular spots downtown, “when I’m not working here—which isn’t often.”

One of those spots is Tsunami, a trendy sushi joint on the rooftop of Shaw Center for the Arts. After an afternoon spent perusing the center’s LSU Museum of Art, plus its two galleries and sculpture gardens, Tsunami is a lively spot to toast the day with a glass of sake. Several of the people crowding the bar are lobbyists; others are professors. Still others have nothing to do with the college or the capitol—they simply enjoy the atmosphere at this downtown hotspot, especially the panoramic views of the riverfront. Standing on the rooftop and sipping a cocktail, they can while away the evening doing something that was unimaginable a decade ago: people-watch.

Taste the Town

Located between the capitals of Creole and Cajun cuisine (New Orleans and Lafayette), Baton Rouge offers a dining scene that borrows from both traditions—with a dash of its own seasoning thrown in for good measure. Not-to-miss restaurants include the Little Village, a pioneer of the city’s fine-dining scene and a great place for Italian with a Louisiana twist; City Pork, a chain of barbecue joints helmed by rising-star chef Ryan Andre; and Beausoleil, a French-Southern restaurant helmed by a couple of Galatoire’s expats.

Drink Up

Like many Louisiana cities, Baton Rouge considers any hour happy hour. Its whiskey scene is exploding, with bars like Lock and Key and the River Room offering a wide selection of bourbons, ryes, and moonshines. (Lock and Key takes its whiskey program so seriously, it stashes its vodkas and tequilas below the bar.) Olive or Twist is Baton Rouge’s dedicated cocktail lounge, while Radio Bar offers a wide selection of craft brews. Speaking of craft brews, Baton Rouge is rightfully proud of its two homegrown breweries, Tin Roof and Southern Craft. In a state with only a handful of craft breweries (Louisiana laws make them difficult to operate), a city with two—both of which have tasting rooms and tours—has something to toast indeed.

Stay Awhile

Baton Rouge may be experiencing a hotel boom, but the Stockade Bed and Breakfast has offered visitors a charming place to stay for twenty-three years. Situated on the site of a former Union stockade that’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it welcomes guests with six elegant rooms and a full Southern breakfast.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-218x150.jpg)

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)