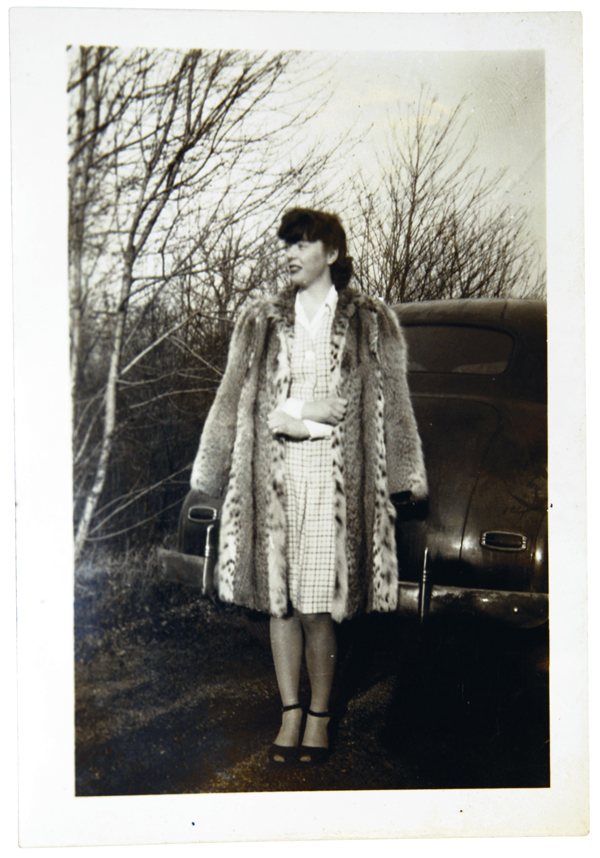

My grandmother was not the prettiest girl in Newell, West Virginia. She was striking, to be sure. Redheaded. Pale and moon-faced. Her body somehow both thin and curvy, with dips and hollows that pooled the fabric of her dresses like creek water. She had appeal. Charisma. But mostly, she had style.

My grandmother was not the prettiest girl in Newell, West Virginia. She was striking, to be sure. Redheaded. Pale and moon-faced. Her body somehow both thin and curvy, with dips and hollows that pooled the fabric of her dresses like creek water. She had appeal. Charisma. But mostly, she had style.

Style was not something many women dared to have in midcentury Newell, a sooty pottery town where dreams were confined to winning the company baseball game or a weekend dinner in Pittsburgh. In fact, many considered a reach for style to be a reach too far, a slap in the face of the land they were born to, a humble place full of humble folks who made do with the crumbs of life and complained little about it.

Into this world was born my grandmother, who came out screaming and never really stopped. Aneita Jean was dramatic, flirtatious, a Southern belle diva who’d never set foot onstage yet innately recognized the thrill and value of making an entrance, be it with a bawdy joke or a floor-length satin gown cinched with a brocade obi sash.

She was raised by an impecunious Scotsman, who nonetheless kept himself and his family of five children dressed neatly and tidily, hems sewn straight, shoes wiped clean, so as to elevate their status in appearance, if nothing else. My great-grandfather gardened in a necktie, and from him, my grandmother learned the value of looking the part: how a well-tailored garment could silence disdain and assumption.

Of course, being the type of woman she was, my grandmother took it several steps further, surmising if clothes could solicit respect, then they could also encourage other feelings and behaviors. (Which is not to suggest she dressed inappropriately, but she did smudge the line every now and again.)

And who could blame her? My grandmother was an outsized personality living in a suffocating Appalachian holler, where difference of any sort was viewed as a threat to the working order. For her, housecoats and sensible shoes were the equivalent of disease. So she opted instead for beaded aqua gowns and heavy felts and reams of canary chiffon and asymmetrical hats studded with costume brooches. Had she been born in other circumstances, she might have been Peggy Guggenheim or Elsa Schiaparelli: quirky, loud, impossible to ignore. Like her father before her, my grandmother dressed for the life she wanted instead of the one she had.

Even if she was only washing dishes, her style caused no small amount of breathless gossip and envy among her peers, who viewed her sartorial choices as both an affront and a play for their husbands—pettiness my grandmother laughed off, though deep down I knew it wounded her.

Her default style may have been provocative, but to assume she was suiting up to seduce men was a misread. Like most fashionable women before and since, my grandmother used clothes to communicate that she was a woman of layers and depth who thought enough of herself to bother looking good. She couldn’t understand why every woman didn’t crave an existence more beautiful than the one they were handed. Why the women around her couldn’t see that their only power in that time and that town lay in the way they carried themselves. And that the garments they chose gave voice to wants and desires they couldn’t otherwise express.

Never a woman of means, my grandmother managed to amass an exquisite wardrobe (many pieces gifted by her scores of suitors), a collection that, when she grew older, she displayed on rolling racks in the basement of her small row house like costumes in a museum.

As a girl, I remember weaving in and out of those racks, the crinolines and silks brushing against the skin of my bare legs. Sometimes I would play dress up, and my grandmother would tell me the story of the gown or the jacket. “I wore that on a date with your grandfather at the Elks,” she’d recall. Or “I wore that for the factory picnic.”

As time wore on, she didn’t falter. My grandmother stayed chic and ahead of trend even in her final years, when she’d be the only woman in the nursing home common room working a scarf or laced up in midcalf suede booties, her lipstick fresh and hair done.

Dazzle was in short supply in the nursing home. Just as it had been in West Virginia. Just as it is in life. My grandmother took fabric and flair and no small amount of nerve, and wrenched style from the dust.

We should all be so brave.

This article originally appeared in our Spring/Summer 2016 issue of Style Book.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)