Photograph by Christopher T. Martin

Between two peaks on Grandfather Mountain they’ve replaced the fifty-year-old wooden footbridge with one made of galvanized steel, so the famous mile-high swinging bridge doesn’t really swing anymore—but it sings.

Step onto the spidery silver span, hanging from twin towers eighty feet above the canyon below (America’s highest suspension footbridge at a mile above sea level), and you’ll hear the merry whistle of wind whipping through its slats, a mellifluous accompaniment to the celestial panorama spreading as far as Charlotte’s skyline a hundred miles away. The rolling mountains—which first rose an eon ago when Africa collided with North America, their majestic contours now gentled by hundreds of millions of years—seem to embody time itself. Whatever angst you carried up that 6,000 feet (whether by car or foot) recedes in what feels like an encounter with eternity.

Such is the tonic of North Carolina’s High Country, the state’s northwest corner and home of the highest mountains east of the Rockies. On the drive from Atlanta, the temperature drops twenty, thirty, even forty degrees. Along its ridges, highways so snaky they’ll make you queasy are redeemed by heart-stopping views, including the spectacular vista from Linn Cove Viaduct, an elevated ribbon of concrete that has graced countless magazine covers, including ours in October 2010.

For twenty years, my base of operations here was my parents’ summer home in Banner Elk. Ever since we sold it three years ago, my husband and I have been hunting for the quintessential Carolina mountain inn—ideally a cozy historic one with towering stone fireplaces, a coffered ceiling, screened windows, quiet nooks for reading or private conversation, and luxurious bedrooms. Not to go all Goldilocks on you, but in my opinion, Cashiers’s High Hampton Inn is too rustic for a romantic getaway; Asheville’s Grove Park Inn too corporate. But the Eseeola Lodge in Linville (open May to October) is just right. Never heard of it? That’s part of the charm.

Linville is an old-money hamlet, where wealthy “cottagers” have been vacationing since the turn of the twentieth century—hence the low profile. The town’s half-timbered, steeply gabled homes are marked with understated, carved wooden signs—Randolph 115, Bailey 181—as if they were staking out mere camp cabins.

The twenty-six-room lodge itself dates to 1892, though the original burned in 1936 and an annex took over, covered with the American chestnut shingles (since replaced by poplar) specified by the inn’s renowned architect, Henry Bacon, best known for designing the Lincoln Memorial. The requisite great room is bookended with stone fireplaces, and the paneled dining hall has a positively baronial bar, its cathedral ceiling flanked by rows of crested flags. Guest rooms—each with a private, bark-covered porch—retain enough original fittings to give them character, enough contemporary furnishings to provide comfort. Lushly manicured grounds include a creek of fat trout, impossibly vivid perennial borders, and of course, croquet (“traditional attire preferred”).

A block away is Linville Golf Club, with a course designed by Donald Ross in 1924. Though private, the course is open to guests at Eseeola ($120 with cart). Golf Magazine ranks it among the top 100 “Courses You Can Play.” Elevated tees and greens, tucked against mountain foothills, make for dramatic fairways, but you’ll need to concentrate on your short game to keep the ball from rolling off the compact, sloped greens.

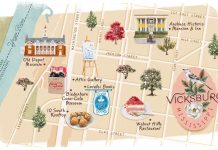

The town itself is little more than a crossroads. Visit the Old Hampton Store for a tender pulled pork sandwich, Cheerwine, and live bluegrass music. Next door is 87 Ruffin Street, a folk art gallery where we spotted a painting of Marietta’s Big Chicken. The Tartan Restaurant, in a squat stone building within walking distance of Eseeola, is a throwback meat-and-three that nods to the area’s Scottish heritage, celebrated every July during the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games, one of the largest clan gatherings in the nation.

Linville is a central location for exploring the three B’s: Boone, Banner Elk, and Blowing Rock, each within a thirty-minute drive. Home to Appalachian State University, Boone is a bohemian college town. Banner Elk is a sleepy village that this month hosts its famous Woolly Worm Festival (October 20 to 21). Blowing Rock is so quaint, it was the model for Jan Karon’s Mitford series. Pleasant little shops with cheerful awnings and boxes of geraniums offer antiques, gifts, rugs, and resort wear. Lunch outdoors at the Village Cafe, a local favorite hidden down a stone path next to Kilwins ice cream shop, or Crippen’s, which is more of a culinary destination (its North Carolina sea beans with mango, currants, and pineapple vinaigrette was one of the most memorable salads I’ve had in years) in a rambling old house. But don’t be tempted to stay for dinner; every road back to Eseeola is a mind-bender at night.

Plus there’s no reason to stray from the dining room at Eseeola (jackets required at night). Opt for the American plan and breakfast and dinner are included in your daily fare (from $375 for double, or $269 with breakfast only). As you might expect, the genteel kitchen serves perfectly rendered continental dishes like coq au vin or boeuf bourguignon. Updated starters—like the goat cheese, beets, and watermelon in July—keep the menu from getting stodgy. And the chewy, house specialty macaroons practically guarantee sweet dreams.

This article originally appeared in our October 2012 issue.