Photograph by Taber Andrew Bain/Flickr

A while back, a conspiracy of kindness unfolded like an unassuming flower in my hometown.

The haircuts of a beloved barber in the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s began to falter in their military precision. His clientele, unanimously concluding that his feelings trumped their vanity, made a pact to continue submitting to his clippers, while wincing imperceptibly into the mirror. Some of them slipped into a more feminine salon for damage control afterward, but one customer who was already shiny in the pate just shrugged and said, “What’s one hair out of place when it’s all I got?”

These gestures can happen anywhere, but I associate them more with small towns, where we know each other’s history and tender spots, for better and worse.

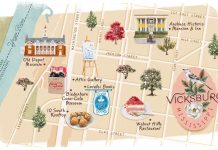

I grew up in Cleveland, population 3,410. The town has more than doubled in size since my childhood but still requires no more than two stoplights. For long stretches, I resided “away” and traipsed through urban grit, only to wash up here every few years like a dazed refugee after a job or relationship went apocalyptically bad. So here I am again, y’all, this time as rooted as an Irish tater—don’t bother with the fatted calf.

“In the great cities we see so little of the world, we drift into our minority,” wrote W.B. Yeats. “In the little towns and villages there are no minorities; people are not numerous enough. You must see the world there, perforce.” Lord knows few “minorities” of any sort occupy this pocket of Appalachia, where diversity boils down to Baptist, Methodist, or Holiness, but the intimacy of scale appeals to the idle anthropologist in me. Cleveland remains obstinately mule-paced—part of its beauty and its bane, its comforts and its claustrophobia, and the reason it balms my nerves just slightly more than it irritates them.

To live as an adult in the small town where you grew up means you collide head-on with your past every day. I cannot dash into the grocery store without running into someone with whom I went to school, church, bed, or a family reunion—or some awkward configuration of all four. We may nod and speak or avoid eye contact altogether. No matter how we furiously erase

and revise our personas as we age, part of us remains frozen in time here. You may have starred in some Caligula-like adventures in the Big City, but to your old classmates, you will always be that bespectacled, bucktoothed wallflower.

For teenagers coming of age here, the only force stronger, deadlier, and more excruciating than hellzapoppin’ lust is boredom. Of all of the odes to small-town life, I prefer Hal Ketchum’s song with the line “gotta be bad just to have a good time.” You become resourceful with cow pastures, rivers, muscle cars, each other’s bodies. My pubescent landmarks start with the Dairy Queen; a cherry Mr. Misty float might as well be Proust’s madeleine. My first kiss was at Country Roads skating rink. That boy grew into a poker-faced deacon, and now when I see him I wonder if he flashes back to the rink’s rainbow-winking disco ball the way I do.

Government eavesdropping does not incense me personally because I never assumed any privacy to begin with; everybody knows your business here, a de facto policing of the social compact. You can flip off other drivers on I-285, but in Cleveland, you likely will encounter them in church, so don’t do it. Likewise, don’t cheat anyone or steal someone’s mate, and remember when you gossip that your listener has cousins—the gene pool is the size of a raindrop. Conversely, you also must develop a flinty disregard for what these people think of you, and that resilient, high-hat carriage is easy to spot in a crowd. The city-bred do not have to weather the lingering personal scandals of a small town.

While social conformity here rivals that of the Amish, people also make allowances. I shudder to check my credit rating, but my family’s “good name” usually floats me. I used to bristle when an outsider clucked that I must have been “sheltered.” My reflexive response was to self-immolate, to bring down that roof around me, but increasingly I respect the infrastructure—the sturdier the heart pine, the better. Just when I rail like George Bailey at crummy Bedford Falls, some freckle-faced good ol’ boy cheerfully submits to a bad haircut, and I know I am sheltered where I belong.

This article originally appeared in our August 2013 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-218x150.jpg)

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)