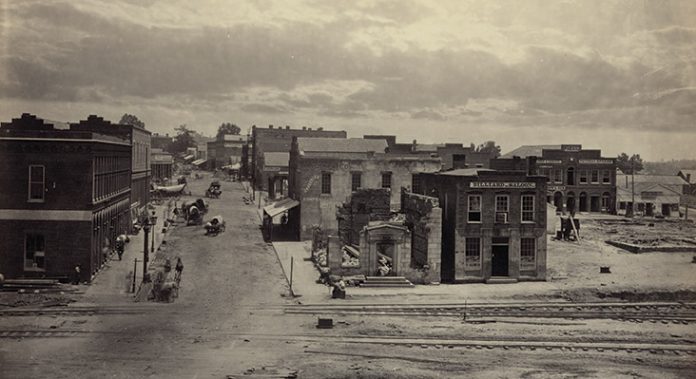

Photograph courtesy of the Atlanta History Center

For eight hours on the blazing day of July 22, 1864, 74,000 young men fought on the rolling terrain of southeast Atlanta. As the cannon smoke cleared and each side retreated, the four-mile-long field of combat held the bodies of more than 12,000 dead or wounded soldiers. The Battle of Atlanta was by no means the biggest or bloodiest of the Civil War, but it played a crucial role in bringing the conflict to an end.

Outnumbered two-to-one, the Confederate Army defended a city protected by ingenious fortifications and bolstered by residents determined to outlast the Union troops. More fighting followed—at Ezra Church, Utoy Creek, Jonesboro—and more troops died. For weeks, the Federals shelled Atlanta, destroying homes and killing civilians; the first to die was a little child.

In early September, Union commanders strode into Atlanta, where they were met by city fathers waving a flag of truce. A few days later, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s telegram—“Atlanta is ours, and fairly won”—reached the desk of President Lincoln. Across the Union, the fall of Atlanta was celebrated with 100-gun salutes, parades, and bell-ringing.

The battles and military maneuvers and casualty counts are what matter in history books. But what matters for Atlanta, what has lingered in our civic DNA for a century and a half, is not the combat, but what happened afterward, beginning when the feisty little town at the intersection of the South’s railroad lines suffered the indignity of an occupying army—which set up camp in front of city hall, raided stores and farms and cellars, and tore down houses for firewood—and ending when Sherman ordered all residents to evacuate and then set the city aflame before heading off for the Georgia coast.

The destruction of Atlanta was crucial to the formation of the city we know today. Unlike other towns where antebellum structures were preserved and residents remained in place, Atlanta was wiped clean. Being forced to leave, then return and rebuild from the ground up gave Atlanta a fresh start, and instilled a sense of reinvention—from tiny Terminus to Gate City of the New South—that permeates Atlanta still.

As Atlanta was reborn, it welcomed those who wanted to remake themselves in the aftermath of a long and bloody war. With the influx of refugees from across the South and the arrival of opportunistic newcomers from other corners of the country (also known as carpetbaggers), Atlanta repaired its roads and homes and buildings and also assembled a new populace, creating the mix of old and new, Southerner and Yankee, black and white, that defines us to this day.

But the facades of freshly constructed buildings and the energy of newcomers could not completely heal the psychological damage. Bitterness smolders 150 years after Sherman’s bonfire.

Some of us simply resent that Atlanta is still labeled an upstart. We have a collective chip on our shoulders about constantly being compared to other cities. How many times do we have to explain? It was all burned down, we vent. Stop expecting Atlanta to look like Charleston or Savannah; that would be possible only by altering the laws of time, space, and—presumably—thermodynamics. Stop chiding Atlanta for not growing factories and skyscrapers as quickly as Chicago and New York; they boomed while we crawled back from economic desolation.

For others, the simmering anger has been more insidious. There are still those—here and throughout the South—who resent the war’s outcome. It’s no wonder that Margaret Mitchell, author of the definitive tribute to a mythical Old South, grew up here. She’s buried in Oakland Cemetery, as are 6,900 Confederate soldiers, whose final resting places lie just down the hill from where General Hood watched the Battle of Atlanta. If you want to wallow in the humility of defeat, there is no better place than one that the winners vanquished and then trashed.

But fortunately, moving on rather than wallowing is the hallmark of Atlanta’s personality. This is the city that has always been too busy—whether for hate or introspection or mapping out a logical transportation grid. By 1880, less than two decades after being razed, Atlanta had snagged the title of Georgia’s capital and surged to twelve times its prewar population, the fastest growth of any postwar city in the nation.

In the words of Franklin Garrett, the city’s best-known historian, “Atlanta had no inhibitions, no birthright to lose. Never a typically Southern city before the war, it would not become so afterwards. From the ashes of war, it could start anew in any direction.” And 150 years later, we’re still forging ahead.

This article originally appeared in our July 2014 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)