Doug Peterson sells the last thing anybody would expect from a college professor working in rural Georgia: caviar. But just outside Chattanooga—three hours northwest of the University of Georgia, where he works as a professor of fisheries and aquatic sciences—Peterson produces the state’s only sustainable caviar at a 5,000-square-foot facility in the town of Cohutta.

Caviar, or salt-cured sturgeon roe, is one of the world’s most expensive delicacies, fetching as much as $400 for just a few teaspoons. But in the Caspian Sea at the southwestern tip of Russia, long one of the biggest sources of sturgeon, overfishing and pollution have crippled the breed. Elsewhere, environmental degradation and dams blocking migration patterns have lessened the species’ numbers. World organizations estimate that sturgeon populations have declined by as much as 70 percent since the early 20th century. As a field biologist specializing in wild sturgeon, Peterson wanted to do his part to help save the species. “I began to think of a way that we could produce top-notch caviar, as good as anything you can get from the wild,” Peterson says. “If we could convince chefs and diners that our way of doing it was better than killing wild sturgeon while they’re trying to spawn, we’d be golden.”

Worldwide, there are only about 90 caviar farms. It’s a numbers game: It takes $1 million to $3 million to start a proper sturgeon farm and six to 10 years before female sturgeon reach sexual maturity and their eggs can be harvested. Returns on investment don’t follow for many years. Investors, unsurprisingly, are wary. But because Peterson wasn’t interested in running a commercial-scale operation, he needed considerably less money, which he acquired over time in part through a UGA grant. In 2003, he loaded his first batch of Siberian sturgeon into massive tanks filled with fresh spring water from the North Georgia mountains.

Photograph courtesy of UGA Team Sturgeon

In 2009, Inland Seafood became the first to distribute Peterson’s caviar to restaurants. “I’ve been studying caviar for 30-something years. As far as consistent quality, this is as good as it gets,” says Bill Demmond, Inland Seafood’s COO. Today buyers include Empire State South, Lusca, Restaurant Eugene, and Aria.

Any profits are dumped back into sturgeon research, which appears to be paying off: Sturgeon populations are beginning to make a comeback in the Atlantic and the Altamaha River. And farmed caviar production nearly doubled from 2005 to 2010, according to International Aquatic Research. Peterson hopes that farm-raised caviar will one day account for a majority of the world market. That’s still a ways off, considering just 2 percent was farm-raised when Peterson started, and he’s doubtful that the wild Beluga population will ever recover in the Caspian Sea. But nearly 6,500 miles away here in Georgia, the species’ future grows brighter by the bite.

How to harvest caviar

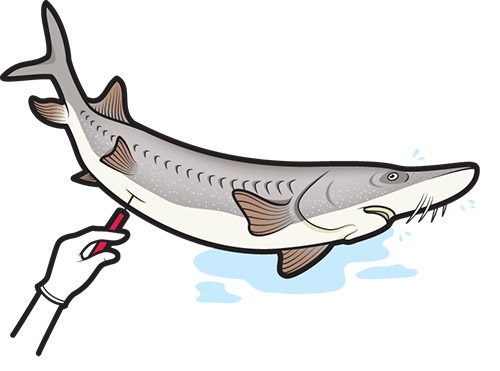

1 Female sturgeon produce eggs (or roe) when they reach sexual maturity (between six to 10 years of age). During ovulation, a few eggs are extracted from the fish’s ovaries and checked for size, texture, and color.

1 Female sturgeon produce eggs (or roe) when they reach sexual maturity (between six to 10 years of age). During ovulation, a few eggs are extracted from the fish’s ovaries and checked for size, texture, and color.

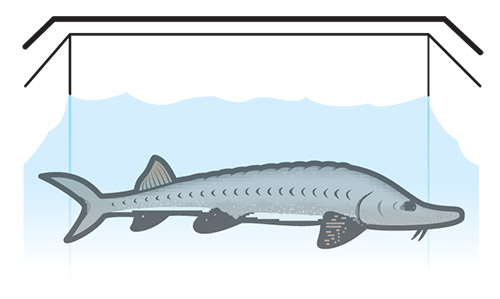

2 Females whose eggs aren’t up to standard are returned to the tanks and checked again months later. The rest of the fish are moved to another tank of fresh spring water.

2 Females whose eggs aren’t up to standard are returned to the tanks and checked again months later. The rest of the fish are moved to another tank of fresh spring water.

3 Ice is slowly added to the tanks to cool and calm the fish, making them immobile. Females are then killed with a quick blow to the head. The ovaries are removed, and the flesh is processed into fillets.

3 Ice is slowly added to the tanks to cool and calm the fish, making them immobile. Females are then killed with a quick blow to the head. The ovaries are removed, and the flesh is processed into fillets.

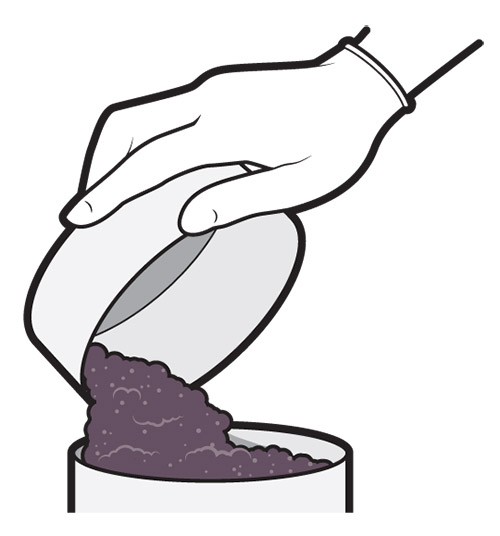

4 The fish’s ovaries are opened and gently rubbed across mesh screens, which separate the delicate roe from the ovarian membrane. The roe are rinsed in water, drained, salted, and then chilled on ice.

4 The fish’s ovaries are opened and gently rubbed across mesh screens, which separate the delicate roe from the ovarian membrane. The roe are rinsed in water, drained, salted, and then chilled on ice.

5 Roe are drained again before being packed into tins and cured for two to six months in a room chilled to 24 to 26°F. Tins are then shipped to distributors.

5 Roe are drained again before being packed into tins and cured for two to six months in a room chilled to 24 to 26°F. Tins are then shipped to distributors.

UGA caviar for sale

UGA caviar for sale

A one-ounce tin goes for around $55 at wholesale.

Illustrations by Brown Bird Designs.

This article originally appeared in our May 2015 issue under the headline “How ‘Bout Them Eggs.”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)