This article originally appeared in our April 1974 issue.

This article originally appeared in our April 1974 issue.

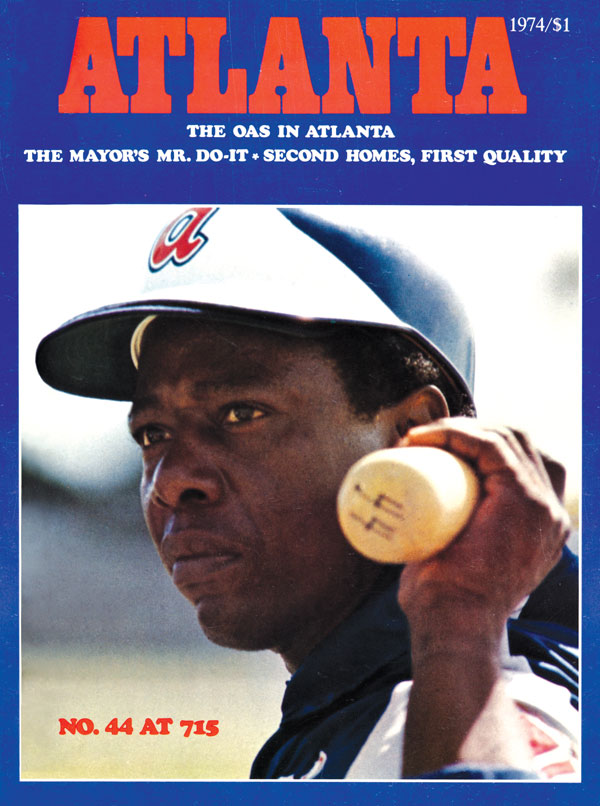

He is almost always just Hank. He is recognized wherever he goes and people want to touch him, get his autograph and pose for pictures with him.

He was 20 when he began these sojourns, swatting No. 1 in 1954, when Eisenhower was President. Hank is supposed to have said then that this first trip around the League was like riding through a beautiful park and getting paid for it.

Of all those playgrounds, only Wrigley Field in Chicago still is used for baseball; everywhere else, he is older than any piece of baseball turf. All has changed save him. Only one player still is performing in the major leagues who was there when he arrived. Seven managers are younger than he. In his first Spring he played the Dodgers in Brooklyn; in his golden Summer, and now with the turning of his leaves, they are in Los Angeles.

Before the Atlanta Braves ever played one game, Hank Aaron already had hit more home runs than all but a half-dozen players then in the Hall of Fame. By now, he has stolen more bases than Rabbit Maranville, hit for more bases than either Babe Ruth or Georgia’s Ty Cobb, caught more fly balls than Tris Speaker, scored more runs than Honus Wagner, and driven in more than Ted Williams.

This is the season—probably the month—when Aaron, at 40, takes a moon walk above one of the most hallowed individual records in American sport, the 714 home runs hit by George Herman Ruth. Only in the last year or two has Aaron attracted the national attention his exploits have merited for years. His statistical accomplishments are so vast and continuous that putting them into perspective is like trying to remember numbers of passing freight cars.

He has gone to the plate more than 11,000 times, hit for more than 6,000 total bases and collected more than 500 doubles. As impressive as all those accomplishments are, the big number is 715. His relentless pursuit of that treasure has made Aaron the single most conspicuous figure in American sports.

The enormousness of it has closed in fast on Aaron, on and off the field. As the climax approached at the end of last season, he was walked increasingly because opposing pitchers frankly feared him. Opposition infields overshifted, trying to force him to hit to right field. Aaron ignored them and took the overhead route; in baseball vernacular, he “went for the pump.” Aaron wants everybody to come in with their hard stuff. When pitchers get shifty, trying to nip the outside corner, he disapproves but adjusts accordingly, grumbling all the while about pitchers who “want to fool everybody.” Aaron prefers the problem of hitting against a man such as the New York Mets’ Tom Seaver.

“A man like Seaver, he says, ‘All right big guy, here it is. Pschoo!’ Why hold on to the ball? Why sneak it in? That’s not what the good dudes do—Gibson . . . Seaver. ‘Here’s the heat,’ they say. ‘Here, you want me? Pschoo!'”

Some baseball aficionados cite such comment as evidence of the massive pressure on Aaron. They also observe the number of times Aaron stepped out of the batter’s box last season, how tightly he seems to grip his bat, the way he questions umpires about strikes. But when Babe Ruth is chasing you, people see things they never noticed before. And, yes, it is a matter of Ruth chasing Aaron, the old legends dogging Aaron’s steps, wraiths in pinstripes hounding him.

Always one to read and answer fan mail, Aaron realizes that while most letter writers are pulling for him, a disturbing number do not want him to hit 715. For some who bode him ill, the reason is that Ruth is a colussus in their pantheon. For others, Aaron’s color is sufficient to denigrate his quest. Letters that begin “Dear Nigger,” and go downhill from there, say far more about the mind of parts of the nation than they do about Aaron. “It bothers me,” he says. “I have seen a President shot and his brother shot. The man who murdered Dr. Martin Luther King is in jail, but that isn’t doing Dr. King much good is it? I have four children and I have to be concerned about their welfare.”

Yet Aaron seems to thrive on pressure: it has made him all the more steadfast in his Olympian ambition.

Perhaps this helps explain why the pressure hasn’t seemed to take a noticeable physical toll. Aaron’s wiry, superbly conditioned body shows only the faintest signs of wear. A consummate and deliberate craftsman, he is the same Aaron players have held in awe for years. An accomplished outfielder with keen baseball savvy, Aaron is said never to have made a mental error like throwing to the wrong base. His quick wrists (at eight inches around, they are bigger than Muhammad Ali’s) still snap the bat with sizzling speed, and he hits what are known in baseball’s dugouts as “frozen ropes.” At 190 pounds, Aaron is only 10 pounds heavier than when he broke into the big leagues 20 years ago with Milwaukee. He is the most steady player in a sport that demands consistency of its genuine heroes.

His record in this respect is scintillating. Only twice has he failed to hit at least .280; once was in 1966, when the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta. His average that year fell to .279, but with 44 home runs and 127 runs batted in, nobody could complain that his hitting was inadequate. Because of his consistency and high performance in so many categories, even an average season for him produces eye-opening statistics. Despite his ability, longevity, consistency and willingness to play, even when injured, the national fame accorded Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Stan Musial wasn’t granted Aaron until last year. Perhaps it was because he did not play in New York, and thereby missed the glow of glory that flooded Mickey and Willie, or that he did not come into the Big City and rip the fence in Ebbets Field as Stan did. Being in Milwaukee and Atlanta did not help Aaron’s publicity value, but all of that has changed. Still, Aaron is somewhat resentful. He remarked plaintively in a recent interview with CBS-TV’s Heywood Hale Broun that “I wish all this fame had come earlier. I’m 40 years old now, and I gotta pace myself . . . can’t go as fast as I once did.”

Being the first ballplayer outside New York or Los Angeles to make it to the media vitals has not been easy for Aaron, a flesh-and-blood Everyman who has demonstrated that a hero need not be mythic. He prefers a subdued lifestyle free of curiosity-seekers and paparazzi; his wardrobe is fastidious, not flashy; he drives a 1973 Chevrolet. As one friend reports, “Hank’s idea of a big night out is dinner at a Polynesian restaurant.”

Photograph by by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In the last six months, Aaron has made TV appearances with Merv Griffin, Flip Wilson and Dinah Shore. Last year he appeared on the covers of publications as disparate as Newsweek and Jet. Now his likeness will proliferate like posters when the circus is due. More recently, he popped up on the sports, business, and entertainment pages, and his wedding last Fall put him on the society pages. Three books on Aaron were scheduled for March and April release, and another will be rushed into print as soon as he cracks 715. Another book on Aaron may be written by George Plimpton. (In August, 1968, Atlanta magazine already pictured Aaron on its cover: that issue featured an extract from a book written by Atlanta Journal sports editor Furman Bisher.)

At the outset of this year, a barnstorming, banquet-circuit tour took Aaron to Chicago, Boston, New Hampshire, Milwaukee, and New York—not to mention celebrations honoring him in Atlanta, and his birthplace, Mobile. While in Los Angeles, Aaron was offered a part in a movie which is to costar Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier.

“I was to play a bartender,” Aaron said. “They gave me about a page of lines to learn, and I was to serve a few drinks, but I turned it down. It would have been fun, but I just don’t want to make another trip to the West Coast. That’s a different world out there . . . they’re too fast. I don’t want any part of it.”

Hank’s business manager, Berle Adams, is determined to “get an organizational structure around Hank that we can work with and try to control.” While Aaron is not a great one for getting to business meetings on time, he has filmed a series of Brut commercials, plugged Lifebuoy soap and Oh Henry chocolate bars, and signed a pact with the Magnavox Corp. calling for payment of $1 million over a five-year period.

The Magnavox pact calls for Aaron to engage in promotional activities, including his own TV specials. At a New York press conference detailing his Magnavox contract, Aaron said he not only was signing his exclusive services but also the balls, bats, uniforms and other memorabilia associated with his career.

“Each ball, each bat, even the uniform Hank uses, will become our possession,” Alfred di Scipio, a Magnavox official, told the New York assemblage. “They will be carried around the country for people to touch so they can feel a part of this legendary event.” Aaron’s Magnavox contract allows his commitments to other companies until their expiration, when his promotional activities fall under the sole direction Magnavox.

Aaron has become much more than a baseball superstar. He eclipses the sports page and is, in the lexicon of Hollywood, a singular merchandising phenomenon. The home of Lt. Gov. Lester Maddox, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Margaret Mitchell and Ralph McGill has put him on a pedestal. The Atlanta Chamber of Commerce and the City of Atlanta initiated a massive “Atlanta Salutes Hank Aaron” celebration which encompasses a citywide Aaron billboard campaign, an Aaron Scholarship Fund administered by the Metropolitan Foundation of Atlanta, and other salutes such as street and school names, and a bust of Hank to be placed at Atlanta Stadium.

At the recent “Atlanta Salutes Hank Aaron Dinner” Gov. Jimmy Carter read a proclamation citing Aaron as an honorary Admiral in the Georgia Navy. Mayor Maynard Jackson awarded him a sterling silver medal, Atlanta’s second highest honor for public service. Explaining why it was not the City’s highest honor, a gold medal, Hizzoner quipped: “I’m saving that one until he breaks the record.” Braves’ announcer Ernie Johnson, observing that a player must wait five years after terminating his playing career to be eligible for the Hall of Fame, commented: “Special dispensations have been granted in special cases in the past, and if Hank Aaron has to wait five years, it’s injustice!”

There is something serenely beautiful in the way Aaron is being honored in Atlanta—a way no black athlete could have been feted as little as 20 years ago. Aaron, while keenly aware of it, takes it in stride: His overall cool throughout the adulation has bordered on the comatose. Now and then he reflects on the magnitude of these tributes: “I have always thought the way I could do the most for my race was through excelling in my conduct on and off the field as a player. Now, because of the position I’m in, I hope I can inspire a few kids to be a success in life. The problems we have in Atlanta are no different than anywhere else: I want to break Ruth’s record as an example to children, especially black children.”

Ivan Allen Jr., mayor of Atlanta when the Braves moved from Milwaukee in 1966, offers this perspective on Aaron: “There was a lot of subtle apprehension about how the South’s first major league sports franchise and its black players would go over. Hank played a major role in smoothing the transition and confirming the end of segregation in the South through his thoughtful consideration and cooperative attitude with everyone, and his exemplary conduct. He taught us how to do it. The first time he knocked one over that left-field fence here, everyone forgot his color.”

Five years ago, the thought that Aaron would be as much a fixture of American culture as Coca-Cola would have been preposterous. The conventional wisdom around the big leagues then was that Ruth’s record not only was untouchable but inviolable, and anyone who thought otherwise obviously had taken leave of his senses. Aaron in less halcyon days remarked: “People keep wondering if I’ll be around long enough to break Babe Ruth’s home run record. I really don’t know. I do know that I will not hang on just for the sake of hanging on—picking up 12 one year and maybe 20 the next and jumping from club to club. I have too much respect for the game of baseball to do that just to chase someone’s record.”

This is the gist of the Aaron legend: immense self-respect. It’s also a kind of class which Aaron attains simply by being himself, a man who would like to pare life to certain essentials but finds it hard. Aaron is first and foremost a baseball player (“The only thing I really know is baseball”) and all the Hollywoodish packaging and grooming cannot obscure that fact. For all his business deals, for all the largesse he has raked in, Aaron seems somewhat uncomfortable about the whole business.

His off-season schedule kicked off at 8 a.m. daily and usually stretched nonstop to midnight: TV commercials, speaking engagements, and discussions with civic leaders—in town one day, out the next. Trying to rap with Aaron during the off-season was a hit-and-run proposition—five minutes here, 10 there, and catch me if you can. The irony is that the acclaim denied him through much of his career now threatens to overwhelm Aaron. In defense, he has developed stock answers for the stock questions he hears every day. His pursuit of the Babe also has become a wish for solitude. Aaron couldn’t wait to get to Spring training this year: “It’s gonna be like a vacation,” he said.

Baseball: That’s where Aaron’s roots are. There he takes his ease; there is his domain. One recalls Braves third baseman Darrell Evans teasing a sartorially resplendent Aaron prior to the Atlanta Salutes Hank Aaron Dinner: “Hey, ‘Supe’”—( short for Superstar)—”how come ya got ‘that fancy jacket on? Whaddya doin’— gettin’ married again?” Hank grinned, but you felt he wanted to take off the damned tuxedo, pick up a bat and start limbering up right there in the Marriott’s Grand Ballroom.

Braves owner Bill Bartholomay once said of him: “One of the few right things I might have done in Milwaukee was to get to know Aaron right away. My admiration for him goes beyond description. He’s Mr. Brave.”

Aaron must admire records because he has created so many of them; yet, for all of the scuffled hysteria over his chase of the Babe, Aaron observes: “To be frank, it is not as important to me as to baseball. The only thing I ever thought about was to be as good as I could. I never thought about being the greatest ballplayer or anything; just to be as good as I could.”

A friend has noted that “for all the commercials, endorsements and business connections, he’ll never be a ‘Broadway Hank.’ The thing about Hank is that he’s really simplified. Simplified. He doesn’t complicate anything. Thoreau would have loved the guy.” So when Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn failed to congratulate Aaron on his 700th home run, and issued an edict warning pitchers not to “groove” Nos. 714 and 715 for Aaron, it was construed as scandalous. Some pitchers had made some offhand remarks about “groovin’ the biggies,” but only Kuhn took the talk seriously.

Other so-called experts on baseball have referred to the architecture of Atlanta Stadium as the real reason Aaron’s about to overtake Ruth. While it is a park without any wind factor, and because of the altitude of Atlanta, the ball rockets over the wall as if launched from Cape Kennedy. One look at this park and you want to pick up a bat. To suggest, as many have, that this is the principal reason why Aaron has pulled even with the Babe smacks of errant folly.

Such minutiae and petty slights, coupled with the Hall of Fame’s lack of enthusiasm for Aaron mementoes, are an understandable source of annoyance to Aaron, although he will not be caught badmouthing Kuhn or the Hall of Fame. “I like to let the record book speak for itself.”

In the last game of the 1973 season, 40,517 turned out at Atlanta Stadium on a rainy Sept. 30 to see if Aaron could finish off the Babe. Each time Aaron came to bat, there it was, louder still: noise, enthusiasm, recognition. In his first three times at bat that day Hank hit three singles. When he popped up in has last at-bat in 1973, the din was enormous. All Aaron had done for his year’s work, at the age of 39, was slam 40 home runs, hit .301, and knock in 96 runs.

When Hank Aaron paused on his way to the dugout that day, it was beyond any mere note of excitement; it was with absolute authority. The only baseball player before Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Aaron who played with the kind of zest and gusto referred to as “black style” was Enos Slaughter.

There was the echo of the tone of one of William Faulkner’s characters who said, standing at the wagon: “Them that’s going, get in the goddam wagon. Them that ain’t, get out of the goddam way.”

Aaron’s in the front wagon.

This article originally appeared in our April 1974 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)