This article was originally published in our March 1996 issue.

This article was originally published in our March 1996 issue.

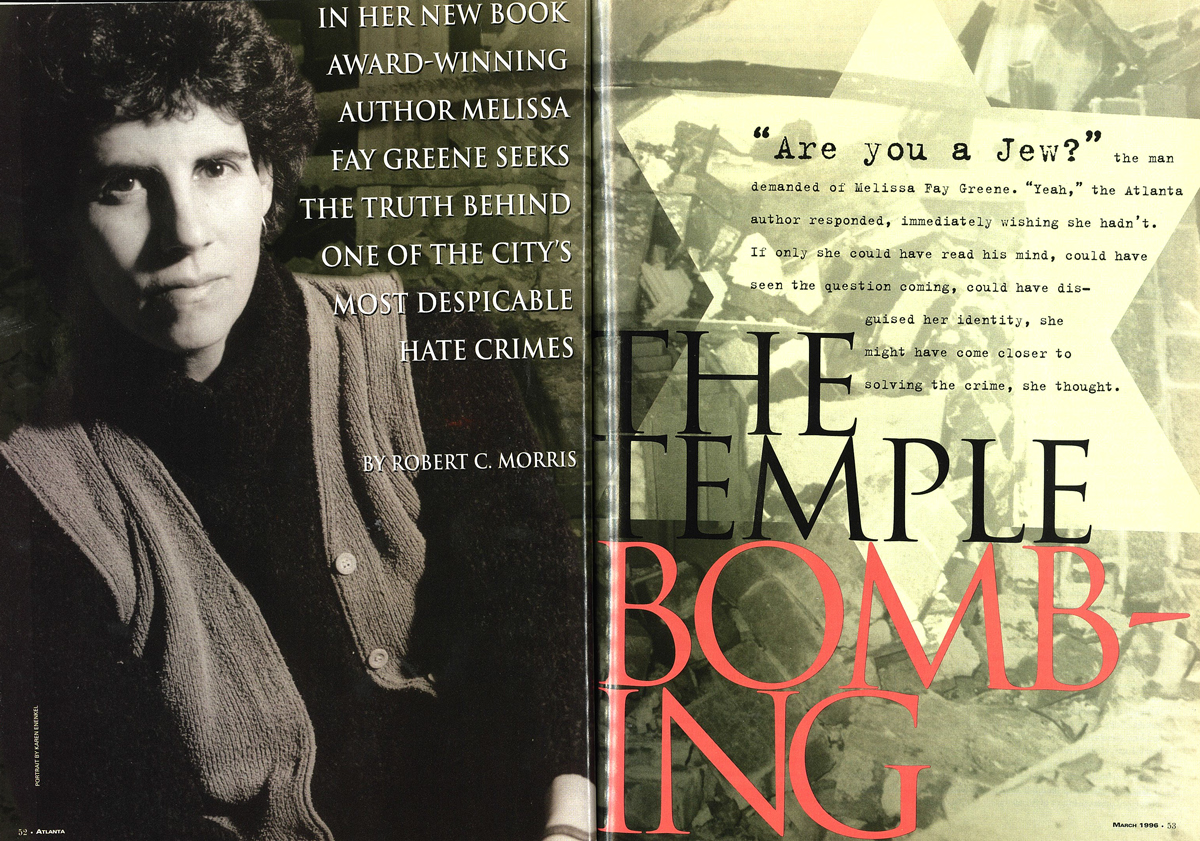

“Are you a Jew?” the man demanded of Melissa Fay Greene.

“Yeah,” the Atlanta author responded, immediately wishing she hadn’t. If only she could have read his mind, could have seen the question coming, could have disguised her identity, she might have come closer to solving the crime, she thought.

Listening on the other end of the phone for the man’s response, she hoped beyond hope that he would agree to the interview.

“You think I’m gonna talk to you?” the man asked. “Forget it.” And he hung up.

Melissa Fay Greene had believed that Wallace Allen would reveal what she needed to solve the mystery of the bombing of The Temple, on Peachtree Street, on Sunday, October 12 1958. At 3:37 a.m. an estimated 40-50 sticks of dynamite exploded, ripping through the oldest and wealthiest synagogue in Atlanta, devastating and arousing deep fears in the Jewish and African American communities. Allen had been accused, indicted, and cleared of the crime.

His refusal to talk created a stumbling block, but Greene’s journey back 38 years to that fateful day was not to be sidetracked. With the Temple bombing the hatred that inspired the Holocaust had infiltrated through the progressive city of Atlanta, Greene thought, and she wanted to find out, once and for all, who was responsible.

Much was at stake. She had already published Praying for Sheetrock, a nationally acclaimed nonfiction account of how the black community in McIntosh County threw off two centuries of oppression, a corrupt sheriff, a violent police force, and found new strength. For her efforts she won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, the Lillian Smith Book Award, The Chicago Tribune‘s Heartland Award, and had been nominated for the National Book Award. She was a 38-year-old first-time author and already the darling of the media and the publishing world. She could be expected to feel on top of the world. But when this tenacious, driven, even obsessive writer was sent home from new York without the prestigious National Book Award, she cried on the plane and resolved to turn her talents to writing about the Temple bombing.

It did not matter to Melissa Fay Greene that she would be forced to confront roadblocks and indignities. She would refuse to turn back when Wallace Allen summarily dismissed her request for an interview based on her ethnic background. She would find another way to get Allen, a notorious anti-Semite who had a German shepherd named Adolph, who kept a picture of Hitler on his mantle. She would find local members of the National States’ Rights Party, of which Allen was an associate, and investigate this gang of anti-Semitic, anti-black, Nazi loyalists.

Her journey was to lead her to the remote and unsavory fringes of Atlanta history. And then The Temple Bombing was finished, this writer had found the soul of the city and opened a window through which to see Atlanta’s future.

After four years of going over thousands of documents, interviewing dozens of witnesses, and reading almost 100 book about Atlanta’s history, Melissa Fay Greene, 43, has honored the promise made to herself on the plane back from New York. Her second book, The Temple Bombing, will be published by Addison-Wesley in April [1996]. Like Praying for Sheetrock, the book takes a step back in time to an era of terror and, ultimately, redemption.

One morning Greene took time off from phone calls from her editor and putting the finishing touches on her book to reflect on what she’d learned as she tracked the story of the Temple bombing. She curls up in a large armchair in the Druid Hills home where she lives with her husband and four children; her large, bushy frock of dark hair frames an elfish, childlike face as she sips coffee from a mug she’s careful chosen because it marks the place where she began looking for clues.

The Garland & Samuel inscribed on the mug, she explains, smiling wryly, refers to a more recent version of the law firm that once represented the five men accused of the Temple bombing. It also happens to be the firm that employs her husband, Don Samuel, who is Jewish.

She savors the irony. It was 1982, she explains, when she and her husband left Rome, Georgia, to come to Atlanta for a job he had accepted with the Garland & Garland law firm. Their friends and fellow Jews at the tiny temple they attended were cool about their imminent departure, but the couple dismissed the brusqueness as a form of sadness that they were leaving. Yet, as moving day approached, one of the older members of the congregation asked, “So the Garlands are hiring Jews now, are they?”

It was to be the first time Greene personally felt the deep and lasting scars left on the generation of Jews that preceded her. After almost 25 years even the mention of the name of the Garland firm brought deep animosity. “That was what the book was supposed to be about at first,” says Greene, “about the regional and ethnic animosities surrounding the bombing of The Temple.”

However, nearly 10 years later, in 1991, when Greene decided to write the book, the scope and dimension had grown to include the hate groups founded to defy segregation, namely the National States’ Rights Party. And when she went looking for answers, she turned to her husband’s law partner, Edward, the son of Reuben Garland, the firm’s founder.

She pulls her knees close to her thin frame as she describes the night of thunder and lightning when she and Edward T.M. Garland drove up to [a house on] West Paces Ferry, or simply “The Mansion” as members of the Garland family refer to it. Ed took her to a cold basement where they rummaged through his father’s old files and soon found boxes filled with the lawyer’s notes and personal accounts.

Buried deep in the documents was one paper that she believed would unlock the mystery of the bombing and bring her book the acclaim she sought. Greene immediately called her publisher and editor in New York and told them she had found a confession. Chester Griffin, one of the five ultimately indicted for the bombing, had pointed the finger at his fellow detainees. The document laid out who had the idea, where the dynamite had come from, even who had driven the getaway car. Her publisher and editor advised her to call a press conference.

But she told them to wait, and when she hunted further through the papers, Greene discovered that Griffin had later recanted his confession and claimed he had been coerced. Whatever the truth was, she knew she had unearthed the most thorough record of the trial. It was invaluable, and it set her on her trail.

The papers would allow her to vividly recreate the volatile environment that led to the bombing of the Atlanta synagogue. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, the term “states’ rights” was appropriated by a number of groups that rejected forced integration. The worst accepted Hitler as their intellectual leader and opened their meetings with Nazi salutes. Greene began to realize that these men were part of the “lunatic fringe, daydreaming of fascism and race wars.”

But they constituted a fringe that hadn’t been openly denounced by the city’s mostly white, mostly Angelo-Saxon leaders. When the bomb ripped through The Temple in 1958, many Jews were uncertain if the city’s elected and business leaders would side with the Temple leadership, which had been sermonizing about the need to integrate, or keep quiet, which would have been a nod to the radical right.

“It was amazing to me the way the virus of European anti-Semitism got transplanted here,” says Greene, her voice rising to a crackly crescendo.

Through the documents she could hear the language of a Jew-hater: “. . . the primeval secret that Jews were Shylocks, nigger-lovers, God-killers,” she writes. She recognized the language as that of the National States’ Rights Party, who came up with grand schemes to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan in order to spread anti-Jewish sentiment and to spray grass-killing chemicals in the shape of a swastika on the lawn of The Temple.

She further discovered the meek lives these men led. Wallace Allen—who was arrested for the bombing, but not before siccing his dog, Adolph, on police officers—was a handicapped telephone salesman. (Allen died a year after Greene’s unsuccessful request for an interview, but his widow did come forward and talk.)

Another equally angry man was an engineer named George Bright, also arrested and acquitted of the bombing. (In addition to Allen and Bright, three other men were indicted for the bombing, but in the wake of Bright’s acquittal their cases were dismissed.) To Greene’s discomfort, she found that Bright lived in an old house just a few miles from her own home. She met with Bright for hours an found that he still had the old hate left in him and was still pursuing his vulgar Jewish conspiracy theory, though admittedly with a lot less vigor. But most of all, he still claimed his innocence.

“It was weird sitting through hours of that and hard not to blow my cover. I had to mask my feelings,” Greene says, when asked what it was like to confront someone who seemed to hate Jews with such passion. “When I saw them alive today, I realized these ideas continue to be attractive to lunatics decade after decade after decade no matter what language you’re speaking or what color the people are.”

Eventually, this fierce researcher and reporter was forced to accept that she wasn’t going to catch the bombers. She had tried everything, even an attempt to persuade her husband, Donald Samuel, to assist with crucial research. It had been more than a year since she filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the FBI to release their files on the case, and she still hadn’t heard anything. Greene wanted Samuel, who once worked in court opposite the director of the FBI, Louis J. Freeh, to “pull some strings.” But her husband refused, telling her, “Louie doesn’t do favors. That’s why he’s the head of the FBI.”

“I would have liked to solve it,” says Greene. “I was really excited to think that I might have, but I the reader will think that I got close enough.”

In the process, however, she may have unraveled another, more fascinating mystery—the secret of Atlanta’s booming economy, rapid development, and successful Olympic bid.

“I know now the definition of leadership,” she says, assuming a stern, tough pose that contrasts with her birdlike delicacy. “We can thank the leaders of the ’50s who exercised intelligent moral leadership for the booming metropolis that was to come.”

As she dug deeper into the history of the times, she found an incredibly brave and decent man in Mayor William Hartsfield, who went straight to The Temple when it was bombed and immediately and without equivocation pointed the finger at the larger community of racists in his midst. Although no one was injured, pieces of the building were blown 150 feet across the parking lot, a brutal reminder of what it could have done. Standing in the Temple remains, Hartsfield declared, “Whether they like it or not, every political rabble-rouser is the godfather of these cross-burners and dynamiters who sneak about in the dark and give a bad name to the South. It is high time that decent people of the South rise up and take charge.”

Nowhere in the South, not in Miami, Nashville, or Jacksonville, where other Jewish institutions were bombed, or the other cities and towns where church bombings, lynchings, beatings, and cross-burnings had become rampant, was there a white elected leader more disgusted by such acts or more outspoken.

In the special collections section of Emory’s Woodruff Library, Greene found “a treasure,” the papers of Rabbi Jacob M. Rothschild, the proud leader of the bombed synagogue. Soon she was able to piece together a compelling portrait of the rabbi, one of the first white religious leaders in Atlanta to speak out so forcefully against segregation.

Rothschild, who understood that the radical right was attacking him and his temple for their stance on civil rights, not Jewish rights, remained focused and even increased his already vocal opposition to segregation. “What interests me the most is the image of somebody who relied on a higher truth,” Greene says. “Rothschild was moved by the prophets who said, ‘Woe to you who grind the needy under your feet.'”

As she pored over the 18,000 items in the collection, Greene also made a crucial discovery: thousands of letters and telegrams that had come to The Temple immediately after the bombing. A letter from the Custer Avenue Baptist Church. A letter from “the entire membership of St. Mark’s Methodist Church.” And hundreds of personal letters, such as the one on a small folded piece of notepaper that read, “I am filled with shame for the people who did this to your Temple.” Signed: “An Episcopalian.” Inside were three dollars.

Greene realized such acts of kindness “really stunned and encouraged the Jewish community,” which had historically been ignored during times of trouble. And after reading through the material, she understood what the city was saying collectively: “Oh no you don’t. It don’t play here. This is a civilized city. We’re not going to stand for this.”

Even as a child Greene had been a writer—of stories, plays, and novels—but it wasn’t until The Temple Bombing that she looked into the world of her own faith in her nonfiction. “I found a new respect for the social action made available for people through churches and synagogues,” says Greene, who is a member of Congregation Shearith Israel, in Atlanta. “The world does change as a result.”

Just behind where she sits in her large living room is the bust of Bobby Kennedy on a bookshelf, and in front of her is a large window with a view into the woods. In a few short hours her four children—Molly, 14, Seth, 11, Lee, 8, and Lilly, 3—will begin to return home. Her attention now naturally turns to the next generation of Atlantans who, like she did 14 years ago, are moving to the city for a better future.

“I often find myself wondering if all these people pouring into Atlanta really understand the city of Atlanta,” says Greene. Has the city forgotten the importance of its history? Do newcomers understand that it took people of courage and conviction to make Atlanta what it is today? If we forget where we came from, says Greene, “we lose the power to shape our own lives.”

The forces for integration and those for segregation are still with us today. “It was never settled clearly and forever,” says Greene. But Greene believes that one of Rothschild’s favorite biblical passages is key to the future: It is not incumbent upon thee to finish the work, but neither are thou permitted to desist from it altogether.

This article was originally published in our March 1996 issue.