This article originally appeared in our April 1972 issue.

On a Memphis motel balcony four years ago this month, a 30.06 slug tore the life from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His colleague and intimate friend, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, was standing inches behind him when the bullet struck.

“I got down over him and I patted his cheek until I got his attention,” Abernathy recalled days ago. “I know talked. His lips quivered, and his eyes said to me, ‘Don’t you let me down, Ralph.’ It was like an inner voice.”

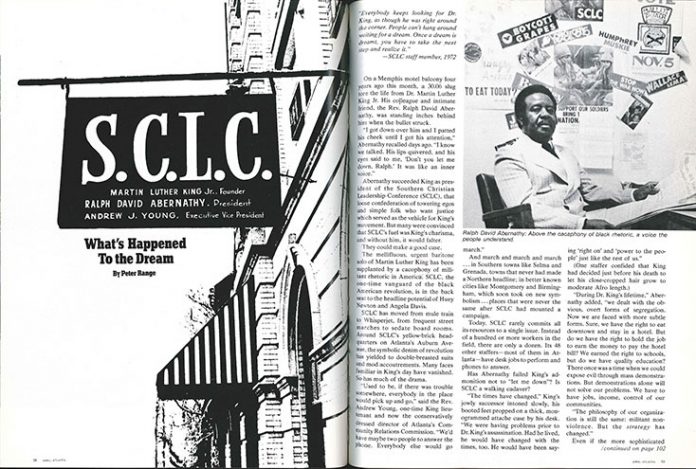

Abernathy succeeded King as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), that loose confederation of towering egos and simple folk who want justice which served as the vehicle for King’s movement. But many were convinced that SCLC’s fuel was King’s charisma, and without him, it would falter.

They could make a good case.

The mellifluous, urgent baritone solo of Martin Luther King has been supplanted by a cacophony of militant rhetoric in America. SCLC, the one-time vanguard of the black American revolution, is in the back seat to the headline potential of Huey Newton and Angela Davis.

SCLC has moved from mule train to Whisperjet, from frequent street marches to sedate board rooms. Around SCLC’s yellow-brick headquarters on Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue, the symbolic denim of revolution yielded to double-breasted suits and mod accoutrements. Many faces familiar in King’s day have vanished. So has much of the drama.

“Used to be, if there was trouble somewhere, everybody in the place would pick up and go,” said the Rev. Andrew Young, one-time King lieutenant and now the conservatively dressed director of Atlanta’s Community Relations Commission. “We’d have maybe two people to answer the phone. Everybody else would go march.”

And march and march and march … in Southern towns like Selma and Grenada, towns that never had made a Northern headline; in better known cities like Montgomery and Birmingham, which soon took on new symbolism … places that were never the same after SCLC had mounted a campaign.

Today, SCLC rarely commits all its resources to a single issue. Instead of a hundred or more workers in the field, there are only a dozen. Its 48 other staffers—most of them in Atlanta—have desk jobs to perform and phones to answer.

Has Abernathy failed King’s admonition not to “let me down”? Is SCLC a walking cadaver?

“The times have changed,” King’s jowly successor intoned slowly, his booted feet propped on a thick, monogrammed attache case by his desk. “We were having problems prior to Dr. King’s assassination. Had he lived, he would have changed with the times, too.

He would have been saying ‘right on’ and ‘power to the people’ just like the rest of us.”

(One staffer confided that King had decided just before his death to let his close-cropped hair grow to moderate Afro length.)

“During Dr. King’s lifetime,” Abernathy added, “we dealt with the obvious, overt forms of segregation. Now we are faced with more subtle forms. Sure, we have the right to eat downtown and stay in a hotel. But do we have the right to hold the job to earn the money to pay the hotel bill? We earned the right to schools, but do we have quality education? There once was a time when we could expose evil through mass demonstrations. But demonstrations alone will not solve our problems. We have to have jobs, income, control of our communities.

“The philosophy of our organization is still the same: militant nonviolence. But the strategy has changed.”

Even if the more sophisticated challenges of jobs and political power were amenable to mass confrontation tactics, it is doubtful that such demonstrations would command the headlines that they did before.

The Rev. Hosea Williams, a firebrand SCLC organizer whose mere presence in a small Southern town sets old-line white leaders boiling, summarized it: “Unless you go out and get you a gun and shoot at some white folks—you can’t just talk about it, you got to shoot at someone now—you don’t make the press. But if you go out and do some hard work like we did in Sandersville, or Columbus, or all over Alabama right now, the press doesn’t write about that—things that would have made front-page stories 10 years ago.”

The last time an old-style campaign got both headlines and results was in 1969, when SCLC joined with union organizers in a 113-day strike to help poorly paid Charleston, S.C., hospital workers win collective bargaining rights. SCLC—including King’s widow, Coretta Scott King—defied state and local police to march and kneel in prayer in the middle of the street. And Abernathy, in best Old Movement fashion, spent 21 days fasting in Charleston jail.

It’s not that SCLC’s reduced cadre of field workers aren’t still manning the trenches in civil rights backwaters. It’s just that their work rarely is treated as news. Few newspaper readers, for example, may realize that:

- Last August, a black man was found, bludgeoned to death, in the trunk of a state patrol car in Ayden, N.C. The patrolman driver was transferred to another part of the state, but not prosecuted. SCLC field worker Golden Frinks led ensuing protests; he and 175 rural blacks were arrested in two days of marching, in one instance having to dodge a police car which charged into the line of march.

- A black girl, 19, was killed last September when a white man drove his car into a civil rights march which protested the firing of black teachers in Butler, Ala. Though charged with murder, the white driver was released the same day on a small bond. Abernathy and some 300 local blacks went to jail for two days in the ensuing protests, while SCLC Board Chairman man Joe Lowery negotiated a nondiscriminatory hiring agreement with the Butler, Ala., power structure.

- SCLC spent about $200,000 of its $900,000 budget in 1971 on a little publicized “War on Repression,” which included welfare marches in Nevada and Wall Street, and a mule train march in Washington on Moratorium Day, in conjunction with other peace groups.

- It backed a march in Daytona Beach, Fla., to protest the low pay of domestic workers there.

- SCLC helped Sandersville, Ga., blacks win a majority on the city council last November, and in the 1970 elections was instrumental in the election of black governments in Greene County, Ala., and Hancock County, Ga.

These events were noted by occasional reporters, but outside the immediate localities (and sometimes even there) the stories rated no better than inside-page coverage. Gone were the battalions of TV cameramen who filmed the clubbing of voting-rights marchers on Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, or the fire-hosing and police dog attacks on public accommodations petitioners in Birmingham.

With SCLC’s lower public profile has come a lower budget.

SCLC raises its money strictly through private donations. It owns what is considered the best mailing list of liberals in the country: some 200,000 names, mostly of whites. It steadfastly resists efforts of other organizations to buy the list, but it recently tested the potency of the list by mailing an appeal for Angela Davis’ defense. In three months’ time, it brought $47,000. The postage cost alone, however, was formidable.

It has shied away from federal grants and foundations.

“They always have string attached,” Andrew Young explained, “like no political activity.” SCLC donors must be especially devoted because their contributions are not tax-deductible.

In the times of the Selma March (1965); the March on Washington, when King delivered his “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial (1963); and of King’s assassination (1968), SCLC’s receipts soared to $2 million each year (non-taxed). Last year’s $900,000 income, although less than half those peaks, hardly suggests a moribund organization.

Shifted emphasis of goals, less dramatic tactics, and lower levels of publicity also have wrought internal changes. Of necessity, the lower budget brought staff reductions. (Not that SCLC pay ever was lavish. Example: The Rev. James Orange, a burly, highly effective field worker who looks utterly at home in dungarees, after nearly 10 tough years in the Movement, recently received a raise to $6,500 a year—plus, presumably, free soul food almost anywhere he goes.)

Many volunteers and some of the old staff are gone because the old glamor is. New recruits and those who remain have accommodated to the new rhythms.

Dorothy Cotton, who has been at SCLC so long she “can’t even remember my life before the Movement,” summarized it: “The hectic days of living and working with Dr. King—wow! It was exciting, beautiful, moving. But it was also killing. You just can’t live at that pitch constantly. One year you can run down the street shouting ‘Freedom now!’ But after a few years, you’ve got to put some flesh on that skeleton. I guess this leads to a more coat-and-tie approach.”

Young, always a coat-and-tie man, left day-to-day work with SCLC first to run for Congress and later to plant his roots more solidly in Atlanta soil with the Community Relations Commission. He remains a member of the SCLC board.

Coretta King also is a board member, and occasionally makes appearances for SCLC causes, but her general absence from the scene continually inspires reports that she and Abernathy are at odds. Both deeply resent these allegations.

A more accurate reading is that Mrs. King is occupied—even preoccupied—with raising her four school-age children, and seeking funds for the Martin Luther King Memorial Center, an ambitious four-block complex of research, meeting and museum facilities planned in the neighborhood of Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King was co-pastor with his father. These commitments, plus a protective secretary, make her almost inaccessible to reporters. (Even after three weeks’ attempts to reach her for this article, she was “not available.”)

“Dr. King used to say we had a team of wild horses,” recalled Tom Offenburger, a white journalist who left U.S. News & World Report to answer King’s clarion. “They could go off on their own thing, but then he could pull it all together again.”

Most of the “wild horses” have left the corral, and gradually—often subtly—SCLC is becoming Abernathy’s organization.

The Rev. James Bevel drifted out of SCLC and was heard from most recently urging a Gov. George Wallace-Rep. Shirley Chisholm ticket.

The Rev. T. Y. Rogers died in an automobile accident.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, often cited as Abernathy’s most potent rival, resigned a few months ago in a much celebrated flap when Abernathy and the SCLC board attempted to curb Jackson’s near autonomy in the organization’s Chicago operation. The handsome, dynamic young Chicago minister promptly established his own black rights organization, PUSH (People United to Save Humanity).

Hosea Williams, most flamboyant and controversial of all the “horses,” was bypassed last spring when young Stoney Cooks, who has less seniority, was named executive director. Williams was placed on leave of absence, made a trip around the world (with funds raised from churches), and returned to write a book. Although Williams was never especially noted for his piety, Abernathy recently ordained his as a minister. Despite their differences, Williams rejects any criticism of Abernathy’s leadership:

“You must be kidding! Abernathy is the most unsung hero in the movement. Dr. King never made a decision that he didn’t consult Ralph David Abernathy. And if Ralph said no, you could bet your bottom dollar that was a dead idea.

“Ralph is not as intellectual as Dr. King, but he’s no dumb man. Everybody knows the guts Ralph’s got. And they know Ralph cannot be bought out. Ralph is able to relate better to the masses than Dr. King was. Dr. King tried. He’d put on some old boots and go down to the pool hall and shoot pool. And they’d accept him a little bit. But as soon as he’d open his mouth—there was something about that man—they’d back away and want to put him on a pedestal. And you’d see ’em looking at him, just wanting to touch him. He was something particular.

“Ralph’s different. Ralph couldn’t do that if he wanted to. There ain’t a bum in the streets won’t say, ‘Hey, Abernathy,’ and throw his arm around Ralph. But that’s the type leader we need today. Black people have developed to the point today that they no longer need a leader they can look up at. They need one they can look at!”

UnKingly though Abernathy admittedly is, and fragmented as the black rights movement is into militants, moderates and separatists, a recent Lou Harris survey showed that black Americans rank Abernathy their most respected leader—a position once held by his friend and predecessor, King.

And as much as some externals have changed, SCLC retains some of its original essences. It is still more a force than an organization, more an idea than a bureaucracy. Mail may still go unanswered, phone calls unreturned, timeclocks unpunched, appointments tardy or unkept.

The slightly shabby headquarters of the Movement that helped change America remains in that focus of black Atlanta, “sweet Auburn,” a soul stew of churches, high-booted prostitutes, “Jesus Saves” neon, billiard parlors, old men in a barber shop, pushers in rakish hats, soul-food lunchrooms, and the prestigious, black-owned Atlanta Life Insurance Company.

It is appropriate that SCLC is there, in the Prince Hall Free & Accepted Masons Building, rather than in the other focus, the West Side, with its Atlanta University complex and $50,000 homes, for SCLC’s strength remains with the poor and troubled.

“You can’t get too poor, and your house can’t be too run down for SCLC,” remarked Thomas Gilmore, whom SCLC helped elect the first black sheriff of Greene County, Ala. (Black officeholders in the Old South have risen in number from about 100 in 1965 to 873 today. Many received SCLC assistance.)

“SCLC is at its very tops out in the Perry Counties, Choctaw Counties, Wilcox Counties,” said a long-time U.S. Justice Department official, a close observer of the civil rights struggle for more than a decade. “They’re the best out in the field working with the regular folks as community organizers.”

“I’ve got 30 people who can ‘turn on’ any county in the South,” claimed Stoney Cooks. “We are the organization that can turn people on. (State Rep.) Julian Bond ain’t got nobody but himself, his wife and children.”

This ability to talk the language of the people not only influences the kinds of projects SCLC undertakes, but also carves a niche distinct from other civil rights organizations and from labor unions.

In a few rural backwaters, where the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 still encounter bitter-end resistance, SCLC projects resemble those of the old days. But increasingly, they are economic and political. Hosea Williams summed it up:

“We’ve got to get the movement out of the streets and into the banks, the chambers of commerce, the college classrooms. We’ve got to stop running to the white community. We’ve got to develop our community. We’ve got to change the slums from a dungeon of shame to a haven of beauty. And then, hell, the white folks’ll be trying to move into our neighborhood.”

SCLC’s major program theme this year is “Politics ’72.” It includes voter registration drives, now rolling at Atlanta University, in parts of North Carolina and Mississippi, and in the Alabama Black Belt. It will support sympathetic candidates in key congressional districts around the country (notably Georgia’s Fifth District, where Atlanta’s Andrew Young will be taking his second shot at the seat).

Abernathy probably will lead a delegation of demonstrators to the Democratic National Convention in July in Miami Beach to apply public pressure to black delegates. SCLC played an important role in organizing black students who elected Shirley Chisholm delegates at the Fifth District Democratic Convention last month.

A formidable propaganda apparatus undergirds SCLC’s politicking. Hundreds of thousands of leaflets, flyers and posters will be distributed to explain voter registration. (One sample, affixed to a wall in the SCLC lobby: “This house is 100% registered to vote. Is yours?”)

SCLC also distributes a half-hour taped radio program to more than 150 black radio stations each week. Called “Martin Luther King Speaks,” it is aimed at devout blacks for whom the Promised Land and the struggle for equal rights are one and the same. Programs often include King’s voice. “Luckily, we taped every speech he made,” Offenburger sighed.

In the area of citizen education and government—as contrasted with politics—SCLC also operates workshops through a tax-exempt Southern Christian Leadership Foundation, which spent $300,000 last year (one-third as much as SCLC’s entire budget but not part of it).

The recession of the late Sixties and early Seventies has handicapped SCLC’s efforts to upgrade jobs for blacks. The organization has been most effective in protest situations such as the Charleston hospital workers’ strike. In 1970, when 500 black and white steelworkers struck in Georgetown, S.C., SCLC helped coordinate their protests into a successful strike. Currently, two SCLC field workers in Birmingham are girding for a re-run of Charleston: More than 2,000 employes from three hospitals already have signed pledge cards asking for collective bargaining.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has been involved in voter education and politics far longer than SCLC. The Urban League has more seniority in solving employment problems. And labor unions would seem on the surface to have enough experience in union organizing to get along without SCLC’s help.

Has SCLC then become a fifth wheel, a drain on the diminished resources of black-rights causes?

If SCLC has a raison d’etre, it lies not in staking out exclusive projects, but in its special ability to talk to and “turn on” poor blacks. NAACP, no slouch at such organization, is more oriented to litigation. Urban League tends to operate more through established channels of power.

As for union support, Abernathy said: “We can get into these hospitals very easy. We speak the people’s language, and they believe in us. They’ve never been in a union before. Once they are organized, they choose the union; we don’t. Soul power and union power are a winning combination.”

“The black American is in the church,” Hosea Williams added. “His whole being is in the church.” Anent his own new preaching role, he explained: “You got to go where the people are before you can take them where they ought to be.”

SCLC’s fate is directly related to the faith it can instill in its constituency. Can that faith survive without the charisma of King? Without the drama and headlines of monumental, all-troops confrontations?”

Four years should be long enough for some sort of answer. Abernathy has found his.

In the first months after King’s assassination, he recalled, trying to operate SCLC was “kind of like being a widower, being the father and the mother to the movement. We had always been together, even in jail.

“The thing I miss most, now I don’t have anybody to laugh with.”

Abernathy lived long in King’s shadow, though he says that people who attempt to compare him with King “are not sincere supporters of the Movement.”

The turning point for Abernathy was a religious experience.

“When ‘d leave the office late at night, I used to walk up to the (King) tomb and listen for his voice. But the tomb never said anything. One night last year I got home from a staff meeting about four in the morning. We had had terrible disagreements, and I didn’t know what to do.

“I looked at Dr. King’s picture in my hallway, and I said, ‘Martin, I’ve done everything I know how. What can I do?’ You may not believe this, but I know he talked to me . . . an inner voice. He said, ‘Ralph, don’t look to me. I don’t have the answer. Look to the Cross.’

“I got back in my car—and drove down to my church and sat in a pew for about an hour. The Cross is always illuminated. Finally, I realized I would no longer find the answers in Martin Luther King. He was a great spirit. He lived. But the answers must come from Christianity.”