Aerial: Ron Sherman; Georgia Avenue: Gregory MIller

This article originally appeared in our July 2013 issue.

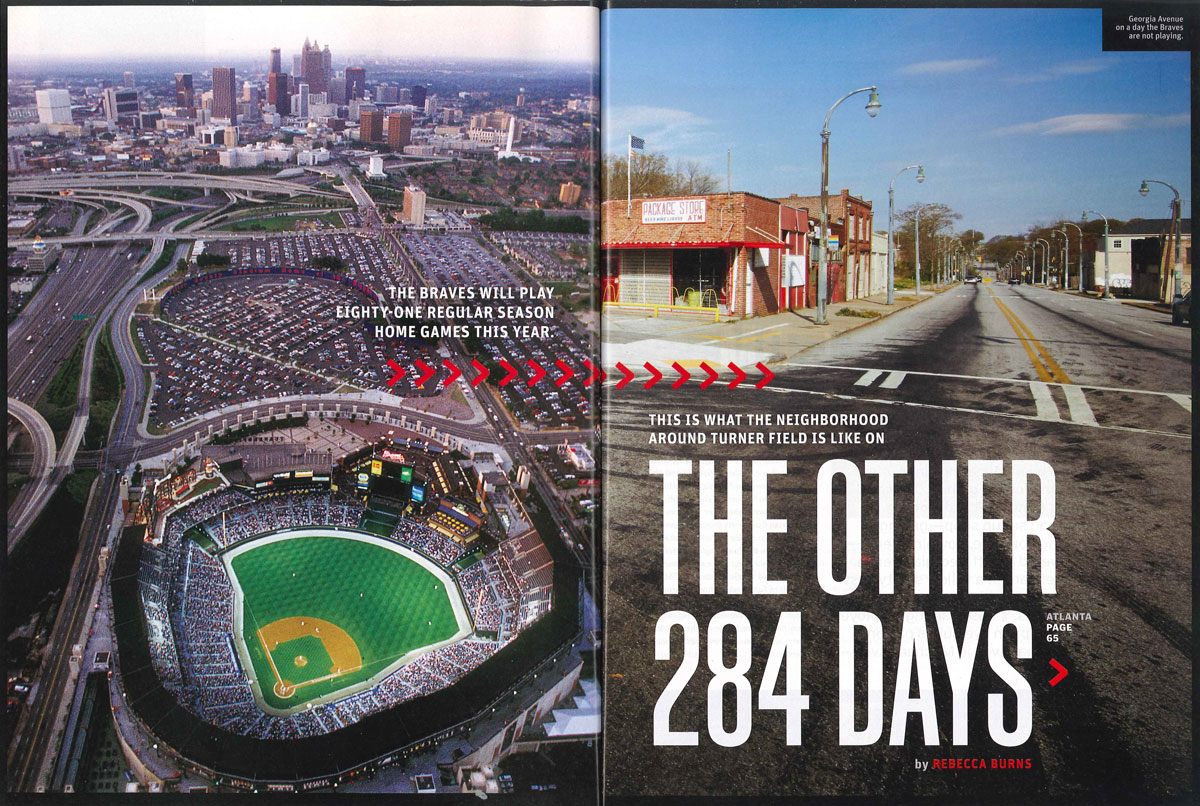

Opening Day. 5 p.m.

The first pitch inside Turner Field was still two hours off, but outside Justin Doll had been tailgating since 2:30. “Oh, we’ll be fine for the game,” Doll said, glancing at his drink. Doll and a dozen of his friends had set up shop—grilling burgers, playing cornhole, downing beers—in a gravel-covered lot off Georgia Avenue. Nearby, an attendant in a yellow safety vest collected twenties as drivers squeezed into the last open spots.

Easy Parking employee Mario Redding kept an eye out as patrons partied. Redding has lived in Mechanicsville—just across the freeway—all his life. In the off-season he works construction, but this is a better gig, he said, gesturing toward the corner of Georgia Avenue and Hank Aaron Drive, and “the big tree” where his boss might be found. The tailgate tents almost blocked the water oak’s branches, and from that direction came the game-day cacophony: police whistles, oontz oontz music from the Pink Pony’s monster truck, radio DJs shouting over car stereos. Somewhere amid the chaos was John Elder, the owner of Easy Parking and the properties that can accommodate 700 cars on game days. When the Braves don’t play, these lots may be eyesores, but on a sellout like today, every sixty square feet represented another twenty dollars.

The Braves would win that night, beating the loathed Phillies 7–5. More than 50,000 ticket holders would stream from the Ted in a celebratory mood, but there would be no celebrating outside the gates. This is not Wrigley or Fenway or even Petco. This is Turner Field, and outside this ballpark there’s nothing to do and nowhere to go but home.

If you had returned a few days later, when the Braves were on the road, you’d have seen this: the stately water oak casting a wide shadow over empty asphalt and gravel. The towering metal gates around Turner Field battened tight. Boarded storefronts. Fresh graffiti. Rubble-strewn lots. Overgrown weeds. And quiet. The quiet that calls to mind a wake.

A half century ago, this stretch of Georgia Avenue housed French’s Ice Cream, Austin’s Grocery, and a dozen mom-and-pop stores. Now there are just two operating concerns: Joe’s Laundry & Cleaners—whose owners triple-barricade themselves behind steel doors, metal grates, and burglar bars—and Fuwah Chinese Restaurant, cash only, where you walk up to a glass-shielded counter, place an order, and wait until the server slides a Styrofoam container of house lo mein through a narrow slot like it’s a sheaf of lottery tickets or a fifth of Evan Williams.

It’s said the Braves generate a $100 million economic impact on metro Atlanta. But it doesn’t take an economist to conclude that little of the team’s monetary power is felt in the neighborhoods around the ballpark.

The story of Turner Field and its neighbors is one of stunted vision, cynical opportunism, halfhearted reform efforts, and misguided renewal schemes. Millions of dollars have been squandered and hundreds of acres left vacant. Around here, thousands of people live below the poverty line while just a handful—some legally, some not—cash in, because it’s more lucrative to park cars on an empty lot eighty-one days a year than to clean up that lot, open a business, and operate it year-round.

This story spans six decades and nine mayoral administrations. Its players include a former president, enterprising developers, absentee landlords, cozily connected politicians, and complacent community organizers. John Elder, the biggest private property owner in the area, is just one of the characters in this civic drama, in which dozens made decisions that ensured the status quo for half a century as not one, but two massive stadiums went up in this impoverished part of town just a mile from the state capitol. With each ballpark came new pledges to jump-start the neighborhood, promises that were broken more frequently than the Braves choked in October.

And like most Atlanta stories, this one starts with traffic.

First came the highways

Turner Field sits at the intersection of three neighborhoods: Summerhill to the north and east, Mechanicsville to the west, and Peoplestown to the south. In the early 1900s these diverse working-class communities were connected to Downtown by streetcars and were within walking distance of factory jobs. First settled by freed slaves, the area later attracted Jewish immigrants, who faced their own brand of Jim Crow bias. Future Mayor Sam Massell was born in the original Piedmont Hospital. Herman Russell grew up here and earned seed money for his construction empire by building a rental house while still in high school.

It was Georgia Avenue that kept these neighborhoods connected. “From Martin Street all the way to Stewart Avenue [now Metropolitan Parkway], there were all kinds of businesses,” recalled Gregory Vaughn Burson Sr., a lifelong Peoplestown resident now in his sixties. “At Fraser and Georgia, opposite that liquor store now, there was a five-and-dime.”

Douglas Dean, a Summerhill native who later represented the area in the Georgia statehouse, clerked at that dime store when he was a teenager while his brother, Maurice, worked in the carpet business their grandfather, W.E. Cox, founded after moving to Summerhill in 1905. Sometimes Maurice got help from a friend, John Elder, who lived in the Eagan Homes projects on the Westside. Elder’s uncle, Jimmie Glass, was a real estate broker based in Summerhill.

After World War II, the area’s more prosperous residents had moved out: Blacks migrated west to Cascade and Collier Heights; Jews north to Druid Hills and Morningside. Factories closed. The poor and working class were left behind, and nobody else moved in. When the streetcar system shut down in the late 1940s, getting to good jobs became almost impossible.

Then came urban renewal. In the mid-1950s, fueled by federal dollars, Atlanta cleared swaths of Summerhill, Mechanicsville, and Peoplestown to make way for roads. The freeways that connected suburbanites to jobs and the airport isolated southsiders from Downtown and created rigid barriers between once-close communities. Growing up in Peoplestown, George Trammell used to walk to Pittman Park, where kids swam free until noon. While the highways were being built, he’d cross a construction site “and get red clay all over my white tennis shoes.” Once the roads were finished, he could no longer get to the park.

Trammell’s family was one of the few that stayed in Peoplestown; in the interest of progress, Atlanta relocated 3,800 households. With fewer local customers, businesses closed. Abandoned houses and apartment buildings decayed. So when city leaders scouted a stadium location, they looked south of Downtown and saw only slums—ripe for further “renewal.”

Next came a stadium

One spring day in 1963, Mayor Ivan Allen drove Charlie Finley of the Kansas City Athletics and sportswriter Furman Bisher to Summerhill. The three men “walked among some old magnolias and weeds” for a while, as Allen later recalled. Then the mayor turned to Finley.

“This is the finest site in America for a municipal stadium,” he said, pointing out Downtown on the horizon, the thirty-two-lane cloverleaf—“biggest interchange in the South”—in the middle distance, and shabby wooden houses in the foreground.

“Mr. Mayor, I agree,” replied Finley. “If you’ll build a stadium here, I’ll guarantee you I’ll bring the Athletics.”

Thanks to luck and league contracts, Atlanta’s team would end up coming from Milwaukee. But the location stuck: In April 1964, Allen hosted a groundbreaking ceremony, and the hastily formed Stadium Authority built a ballpark in less than a year. Another 10,000 residents were forced to relocate.

Thanks to luck and league contracts, Atlanta’s team would end up coming from Milwaukee. But the location stuck: In April 1964, Allen hosted a groundbreaking ceremony, and the hastily formed Stadium Authority built a ballpark in less than a year. Another 10,000 residents were forced to relocate.

The Atlanta Stadium would host the Atlanta Crackers, the Atlanta Falcons, the Atlanta Braves, the Beatles, and the Jacksons. It was there that Hank Aaron hit his record-setting home run in 1974 and the Braves won the World Series in 1995.

But there were few victories beyond the bleachers. Mechanicsville became synonymous with McDaniel-Glenn—a forty-one-acre public housing project riven by violence. In 1992 two bodies were found there within a month; in 1994 a drive-by shooting injured three children. The newspaper dubbed Summerhill a “war zone.” Crack decimated entire blocks of Peoplestown.

Atlanta was shrinking, too. From 1960 to 1990, more than 100,000 people left the city for the suburbs. Leon Eplan, whose grandfather lived in Summerhill—“where third base is today”—was city planning commissioner during both of Maynard Jackson’s administrations and was tapped to help plan MARTA. Eplan advocated for a spur to run from Garnett Station to the ballpark and on to Lakewood. His recommendation was rejected by traffic engineers who said the line would be too busy on game days but not attract riders the rest of the year.

Meanwhile, in Summerhill, as stores shuttered and houses emptied, Jimmie Glass bought up property. His nephew, John Elder, excelled as a linebacker at Booker T. Washington High School, where his classmate George Trammell remembered him as a snappy dresser with close-cropped hair. “We called him ‘applehead,’” recalled his teammate Howard R. Johnson. During baseball season, Elder helped out at his uncle’s parking business. While still in high school, he manned the cloak room at the Royal Peacock nightclub on Auburn Avenue; his best friend, Q.P. Jones Jr., was the house manager. After graduating in 1960, the year before Atlanta schools integrated, Elder went to Dillard University for a semester but left to try out for the New York Giants. He came home and worked at the Peacock, then started a janitorial business. “He was a born entrepreneur,” said Jones. After inheriting property from his uncle, Elder began buying lots himself. “That man bought everything no one else wanted,” Douglas Dean said of Elder. “When the Braves finally started playing good baseball, it started to pay off. I bet before the late 1980s, he never made a profit.”

In 1988 Dean organized a Summerhill reunion. Former residents returned to see their childhood homes disintegrating. Old haunts like the ice cream parlor were boarded up or commandeered by drug-dealing squatters. Dean and neighborhood stalwarts—including Mattie Jackson, who was born in a shotgun shack on Terry Street and has lived in Summerhill all of her ninety-one years—started a community association and drafted a dream plan: solid houses, safe streets, good stores, and stadium parking lots transformed into garages topped with parks and playgrounds.

Their vision collided with a bigger Atlanta aspiration. Dean looked at wooden cottages on Fraser Street and imagined tidy brick houses; he scanned boarded buildings on Georgia Avenue and saw a grocery store. Atlanta boosters looked at decayed blocks with easy interstate access and envisioned a $200 million Olympic stadium.

Before and After

How the area around Turner Field changes when the Braves aren’t playing

Then came the Olympics

One July night in 1993, Shirley Franklin, then a senior policy adviser with the Olympic organizing committee, set out to a tent city on Georgia Avenue to negotiate with Peoplestown activist Columbus Ward and four dozen protesters. The encampment was the latest in a series of protests that began when Atlanta won the Games and the stadium location was announced. The future mayor was not persuasive; the next day Ward and his compatriots disrupted a carefully choreographed photo op, chanting: “Now they sold out the neighborhood! The whole world is watching!”

Occupying Georgia Avenue didn’t halt construction of the 85,000-seat showpiece that would later become Turner Field, but it did push image-conscious Games organizers and local politicians to step up plans to revitalize neighborhoods near Olympic venues. After all, with the whole world watching, why not demonstrate Atlanta’s fabled spirit and spruce up the slums?

The city’s income gap had already been spotlighted by former President Jimmy Carter’s Atlanta Project, a five-year plan launched in 1991 with the goal of connecting Atlanta’s wealthy and poor. As flawed as it was ambitious, Carter’s campaign heightened awareness of blighted neighborhoods like those around the stadium, but its heavy-handed approach—recruiting corporate executives to come up with ideas instead of starting at street level—turned off many of the people it was designed to help.

Unlike other host cities, Atlanta did not have one “Olympics czar” to coordinate building sports venues and upgrading neighborhoods. The Games organizers focused on facilities funded by corporate sponsorships; community development fell to the city and philanthropies.

To mollify neighborhood residents, the Atlanta–Fulton County Recreation Authority and Olympic organizers made an offer: In exchange for the hassle of another stadium in your backyard, you’ll get a cut of the parking revenue—through the entire twenty-year duration of the Braves’ lease.

The pact drove a wedge into already divided communities. Some residents accused lawmakers of buying them out, claiming the “impact fees” could not mitigate the problems created by the new stadium. Protester Ethel Mae Mathews told then Fulton County Commissioner Martin Luther King III that his support for big-money sports over poor people meant “your daddy is turning over in his grave.”

Others, with can’t-beat-’em-join-’em pragmatism, collaborated with the developers who swooped in. Few matched the zeal of Dean, who helped create Summerhill Neighborhood Development Corporation (SNDC), an organization with the nonprofit status required to accept donated land and cash grants, making it an alluring partner for developers. The neighborhood received more than $50 million—in federal, local, and charitable funds—between 1990 and 1996.

Things quickly deteriorated. Developers who partnered with SNDC to convert a hotel into a dorm leased one wall of the building as a giant Coca-Cola billboard, just one grievance angry Summerhill residents cited. In turn, Dean and SNDC frustrated their business partners with haphazard bookkeeping. SNDC’s signature project, the Greenlea Commons townhomes that border the Orange and Gold lots, fell behind schedule and soared over budget; only seventy-six of the planned 259 units were done by 1996, and thanks to escalating construction costs, the group’s builder-partner, John Wieland Homes, lost $600,000.

Meanwhile, John Elder kept acquiring property, one parcel at a time. In 1991, the year the Braves famously went from worst to first, he bought 20 Bass Street for $35,000; in 1995 he picked up 39 Georgia Avenue for $80,000. By 2012 he owned forty-one lots.

Elder’s revenue model had been parking, but as the Games approached he partnered with an old friend, Frank Redding, to try to do more with his properties. Redding and Elder met forty years ago outside the Royal Peacock: “He was a sharp young man, dressed maybe better than me,” recalled Redding. By the 1990s, Redding, a former state legislator, was well connected and still popular despite resigning from the statehouse in 1992 after negotiating a plea on extortion charges. Hoping the Olympics would fuel a Georgia Avenue rebirth, Elder and Redding spent $250,000 to update properties there and were awarded a $500,000 no-interest loan from the city’s development agency. Redding marketed the properties as potential restaurants or stores; complying with Summerhill’s development guidelines, he and Elder turned down “joints and pool halls.” After a few short-term leases during the Games, they ultimately found only one tenant: the architect who drew renderings for their marketing materials.

A Summerhill resurgence never materialized. Elder hung on to his properties and Redding joined Easy Parking. Dean and SNDC sold land to banks and developers rather than partnering on more affordable housing. Most of the developers who bought land in Summerhill built pricey infill houses beyond the means of existing residents.

Today, Georgia Avenue is the border between the neighborhood’s northern section—where houses built in the 1990s and early 2000s are valued at $200,000 and attract affluent, educated professionals—and the southern end, where mostly older houses are valued at less than half as much. Some residents talk about “upper” and “lower” Summerhill, a demarcation as much socioeconomic as geographic.

While Summerhill garnered alternately glowing and critical headlines, quieter progress occurred in Mechanicsville, where Summech, the neighborhood’s development nonprofit, built $95,000 townhomes and renovated fifty-four units in an apartment complex, grandfathering in low rents for seniors. In 2005 Summech allied with the Atlanta Housing Authority, which was aggressively rebuilding its own housing projects. Columbia Residential at Mechanicsville Station—loft-looking apartments with a nice clubhouse and a long waiting list—replaced infamous McDaniel-Glenn.

In 1997 Davetta Johnson Mitchell, former city council member and a protégé of Mayor Bill Campbell, was appointed recreation authority director. With the old stadium demolished and the new one retrofitted for baseball, Mitchell spearheaded Fanplex, an “infotainment” complex with seventy-five video arcade games, an Internet cafe, and a mini-golf course. The $2.5 million center opened in July 2002 on Hank Aaron Drive.

Fanplex flopped. It lost more than $140,000 during baseball season, closed in 2004, and has been vacant ever since. Further tarnishing the recreation authority’s credibility, Mitchell was indicted on theft charges in 2007 for writing herself more than $30,000 in checks. (In 2011 she agreed to a plea deal.)

Burned by the Fanplex boondoggle, the city’s next moves were cautious. In 2006 Franklin’s administration created a stadium tax-allocation district and updated pre-Olympic neighborhood development plans. But in the nine years since Fanplex closed, local government has fueled no progress.

For more than a decade, the Turner Field area has been represented at City Hall by Carla Smith, who lives in Woodland Hills and was first elected as a council member in 2001. Asked to explain the economic disparity in her district—which also includes Grant Park and Lakewood—Smith was terse: “I don’t want to do that. I love all my constituents. Do you have children? You know you can’t favor one over the other.”

Of course, you can love your children and still acknowledge their differences. It hardly seems unloving to point out people need help. You don’t even have to study statistics; just drive down Georgia Avenue—far different in Grant Park than in Summerhill.

“I don’t want to get into that,” Smith said, and set down the phone. After conferring with her staff, she got back on the line. “Here’s what I’ll say: In Grant Park, there are residents who own businesses. That makes a difference.” If you’re going to use Georgia Avenue to make a point, Smith said, talk about the man who owns most of it but lives on the other side of town.

Back on Georgia Avenue

In the neighborhoods around Turner Field, it seemed everyone knew the name John Elder and invoked it like some kind of redevelopment bogeyman. His name appeared in tax records and news stories, was muttered by code enforcement cops, politicians, and neighborhood association officers. But no one could tell me specifics about him.

After trying in vain to reach Elder by phone, I drove to the address on his property records, which turned out to be an imposing McMansion in Cascade—immaculate lawn, big bay windows, shiny silver convertible in the driveway.

Elder opened the door wearing a plush navy blue robe with a Polo logo on the pocket. He had the sturdy build of an ex-jock and even in a bathrobe looked dashing, perhaps because of the Cruella de Vil–like streak of white in his short, jet-black hair.

“Here’s what I can tell you now: If someone shows me the money, they can have the property,” he says. “But I’ll get back to you.”

This scene played right into the story line virtually everyone had repeated: absentee slumlord holding on to dilapidated properties and waiting to cash in.

Elder did not get back to me, but Frank Redding did. We arranged to meet on Georgia Avenue, and a week later we stood in front of number 60, a brick building sheathed in plywood painted the color of creamy coffee and splattered with fresh graffiti tags. “We’ve spent $18,000 over the past five years covering over graffiti,” grumbled Redding.

Photograph by Rebecca Burns

Photograph by Rebecca Burns

As he yanked open a doorway cut into the plywood, I stepped back, certain rats and roaches would scurry out. Redding led the way into . . . an immaculate office: white walls, charcoal-gray carpet, hip little halogen lights on ceiling tracks.

Inside this 1940s store, you forgot the vandalized exterior, unless you wanted to use the bathroom (thieves stole the copper plumbing) or tried to look out the windows (they were framed by a jagged Plexiglas border that covered even spikier shards of glass, all sealed from the outside by heavy sheets of wood). “We replaced all the windows with plate glass, and people broke them. We put in Plexiglas, which is supposed to be unbreakable, and they threw bricks through it,” he said.

We walked behind 63 Georgia Avenue, where on opening day I had chatted with boozy tailgaters. Outside: desolation. Inside: exposed brick walls, intricate wood rafters, a sealed concrete floor, and deep-set windows, the kind of cool space that could house a coffee shop, a nail salon, a gallery, or perhaps a tech start-up. Sure, someone had pilfered plumbing and smashed windows here, too, but I could see why Georgia Power used this space as a hospitality suite during the Olympics.

Outside on Georgia Avenue, we ducked behind more boarded storefronts. At each stop, intact interiors belied the bombed-out facades Braves fans drive past as they hunt for places to park. “Everyone says these buildings are dilapidated. But inside they’re not,” Redding said. It’s an easy and cheap shot to make them a symbol of the neighborhood’s problems, Redding added.

He was right. But perhaps not in the way he intended.

If these buildings were—as they appeared on the surface—decaying and ignored, they would be symbolically no more powerful than any vacant lot or crummy house, just another sign of general neglect in a run-down part of town. But pulling off that plywood to reveal what has been abandoned inside makes these buildings a symbol of something both stronger and sadder: wasted potential.

For decades, Atlanta squandered chances to transform the neighborhood around the ballpark, and nothing symbolizes that better than storefronts that were renovated as showcases when the world was watching, and then covered back up when the spotlight moved elsewhere.

What could come next?

The only remaining portion of Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium is a section of the wall over which Hank Aaron hit his historic 715th homer; it looks lonely in the center of the fifty-five acres of parking lots owned by the recreation authority.

You can see all that asphalt from Invest Atlanta’s offices on the twenty-ninth floor of the Georgia-Pacific building, a vantage point that reveals how close Turner Field is to Downtown. You can envision the ballpark connecting with the rest of the city.

In the city’s latest effort to revitalize the area, Invest Atlanta—the rebranded Atlanta Development Authority—zeroed in on those parking lots. Last fall Invest Atlanta asked planners, architects, and developers—the people who actually would have to build and finance whatever goes around the ballpark—to help brainstorm. Its “request for ideas” solicited suggestions on how to transform parking lots into housing, parks, shops, and restaurants.

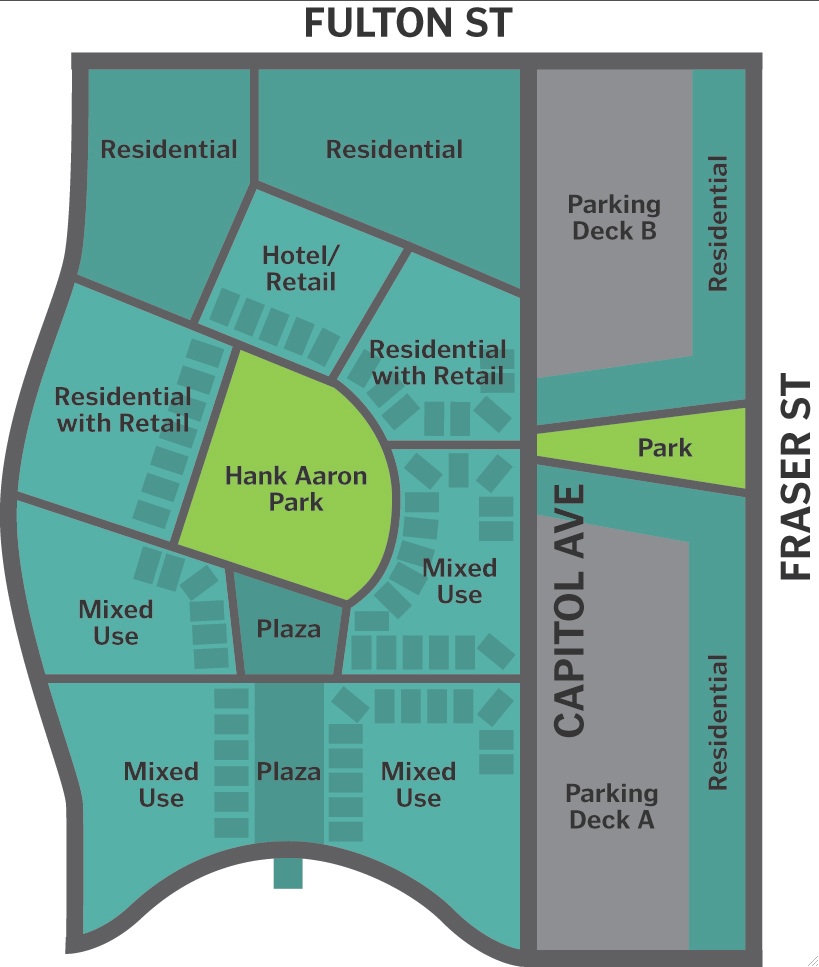

The concept from North American Properties and Russell New Urban Development

The five resulting submissions ranged from fanciful to cautionary. Decatur architect Joseph Flournoy’s concept—concert venues and a gigantic Ferris wheel—is bold but impractical, an impossible-to-finance cousin to Fanplex. Forest City Enterprises, the Cleveland-based developer of the Atlantic Yards/Barclays Center arena in Brooklyn, envisioned a “programming neighborhood” with a Major League Soccer pitch—pretty much ensuring an instant smackdown from Falcons owner Arthur Blank, who is trying to lure an MLS franchise to his new stadium. Builder Edward Bowen, who had talked about Summerhill development for years (more on him shortly), went beyond Invest Atlanta’s brief to include parts of Georgia Avenue in a massive mixed-use scheme.

The most plausible proposal came from a partnership between North American Properties, which developed and manages a large portion of Atlantic Station, and Russell New Urban Development, a division of the construction firm founded by Summerhill native Herman Russell. Their scheme would transform the isolated segment of the old stadium into diamond-shaped Hank Aaron Park, the heart of New Urbanism–inspired blocks of mixed-use apartments, townhouses, shops, and five-story parking decks (see the drawing above).

Its creators seem enthusiastic about the neighborhood’s prospects. “If you were to look at the area from space, you could immediately see the development potential,” said Mark Toro, managing partner of North American Properties. He thinks reinventing the lots would create a ripple effect into the community, much as Historic Fourth Ward Park sparked redevelopment in the Old Fourth Ward. “Five years ago, you wouldn’t walk there—certainly not at night.” Now his company is building the $35 million, 276-unit BOHO4W Flats adjacent to the park and two blocks from Ponce City Market.

Jerome Russell, president of Russell New Urban Development, seems equally confident. Atlanta’s urbanization will continue, he said. “In the fifties, sixties, and seventies, we had people moving out. The next era will be the opposite.”

The final response to Invest Atlanta came from Perkins+Will, the Atlanta architecture firm that hired Atlanta BeltLine visionary Ryan Gravel. The company did not submit schematics or branding ideas or financing projections. Instead, its response reads like a cautionary epistle—“We believe a formal decision-making strategy must be in place”—and then gives examples of how to get people to collaborate, as has been done with the BeltLine.

In the end, collaboration will determine whether any development succeeds or fails. You can’t build attractions near a stadium with only baseball fans in mind (exhibit A: Fanplex). You can’t develop housing beyond the means of its residents and expect a poor neighborhood to transform (exhibit B: Summerhill’s “upper/lower” divide). You can’t open trendy restaurants that serve $8 craft beers and $12 locally sourced burgers to sports fans and expect those restaurants to stay in business year-round in a community where the median annual household income is $22,545.

Andrew Capron can attest to that. At the start of the Braves’ 2011 season, he opened Boners BBQ on Fraser Street, just north of Georgia Avenue. “It seemed like a no-brainer; we couldn’t figure out why no one had done this.” He learned why soon enough. “We just couldn’t turn eighty days into 365,” he said. His restaurant would be busy for two hours before game time, and then—nothing. Boners closed last November. There are rumors that a wing-and-beer joint might move into the spot, but in early June it remained empty.

Tyrone Rachal, Invest Atlanta’s managing director of redevelopment, said if there’s one thing the city learned from the Falcons’ negotiations, it is: “Be as inclusive as possible.” As they weigh interests, Invest Atlanta and City Hall face added pressure: The Braves’ lease expires in three years.

The home of the Braves

It’s a safe bet any baseball-loving executive in town would trade a corner office for Mike Plant’s digs. From Turner Field’s terrace level, his window behind left field has a spectacular view of the whole park. “I’ve come full circle,” said Plant. He grew up in Milwaukee; the first game he ever attended was the Milwaukee Braves.

Without a hometown owner like the Falcons’ Arthur Blank (or the Braves’ former owner, Ted Turner), the Braves’ most visible face is Plant’s as the city negotiates what could be another twenty-year lease with team owner Liberty Media—a conglomerate with stakes in Barnes & Noble, SiriusXM, and Time Warner. The deal might not be as mammoth as the Falcons’ $1 billion arena, but it’s huge. Just replacing the Ted’s seats would run $15 million.

It’s clear Plant envisions a future on the Braves’ terms; the word “control” came up more than a dozen times during our forty-minute conversation. At this stage, control means having a say as Invest Atlanta and the recreation authority review the ideas. In the longer term, it could mean directly taking over as a developer on all or part of the parking-lot improvements.

Whatever happens, for Plant and the Braves, the top priority is reducing game-day traffic. Right now ticket holders arrive late—trapped in forty-five-minute bottlenecks as they exit the freeways—and leave games early, trying to beat the post-game crush. Having diversions for fans before and after the games would spread out arrival and departure times. To that end, Plant wants any development plan to include mass transit. And he doesn’t want it to include huge multistory parking decks. “Have you tried to get home after a Falcons game?” he said.

One other thing will be on the table during the negotiations: Remember those fees the Braves now pay to the neighborhoods as part of the pre-Olympics deal? The team gives 8.25 percent of its parking revenue—an average of $446,000 annually—which to date has added up to at least $7 million, according to the recreation authority. So what’s to show for all that money? It’s a little hard to tell.

Here’s how funds went from the team’s coffers to the community: The Braves gave the money to the recreation authority, which, after taking an administrative fee, turned the funds over to a pass-through organization called the SMP Community Fund. That group split the cash three ways among Summerhill Neighborhood Development Corporation, Peoplestown Revitalization Corporation, and Summech (the Mechanicsville development corporation). When the deal was struck twenty years ago, those three “legacy organizations” were the only area nonprofits with the tax status to accept the fees.

But no one can say definitively how each community used its share of the funds. The Braves never asked. Neither did the recreation authority. The SMP Community Fund was not registered as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit—and hasn’t been consistently audited.

At street level, the “legacy” groups doled out practical assistance. They marshaled crews to clean up houses, helped homeowners avoid code-enforcement citations, drove residents to the grocery store. They funded summer camps and after-school programs run by other nonprofits. Douglas Dean and SNDC hosted a big annual block party. Residents saw some tangible benefits and thus supported the people who ran the nonprofits and the politicians who kept them in place—including Dean, who represented Summerhill in the Georgia Assembly from 1975 to 1986 and 1999 to 2006.

The power structure was—to some extent, still is—incestuous. Dean represented Summerhill in the statehouse, sat on the recreation authority board, and drew a staff salary from SNDC, the very nonprofit to which the rec authority funneled funds. Nonagenarian Mattie Jackson sits on the boards of both SNDC and the SMP Community Fund. Summech’s executive director Janis Ware was on the board of the Atlanta Housing Authority, which partnered with the nonprofit she runs. Columbus Ward represents Peoplestown on the SMP Community Fund board and is both acting executive director and board president of Peoplestown Revitalization Corporation, which donated a portion of its Braves fees to Emmaus House, where Ward worked for thirty-six years.

The recreation authority and SMP Community Fund are now working to impose accountability where little previously existed, formalizing how grants are made and awarding funds to groups other than the legacy recipients. The reform push comes from City Hall. Mayor Kasim Reed tapped Plemon El-Amin, Imam Emeritus at Atlanta Masjid of Al-Islam, one of the city’s largest mosques, to serve on the recreation authority and SMP Community Fund boards and gave those boards a mission: Establish basic governance that should have been implemented decades ago.

The funds donated by the Braves, however, represent just a fraction of the money that’s flowed to the communities in the form of development grants and donated property. Just how much value is tied up in those properties was underscored in 2010 when the SNDC board forced Dean to resign and then sued him, claiming that Dean had collaborated with the builder Edward Bowen and John Elder on a Georgia Avenue development scheme and, without notifying them, had pledged SNDC properties as collateral for a $2.4 million loan in 2008. The suit eventually was dismissed.

Then in 2012 Capitol City Bank and Trust, which held that loan and others, sued Elder and Bowen for missed payments. Elder said he’d been duped by Bowen and pressured by bank president George Andrews, who, like Dean, was on the recreation authority board. Bowen claimed he had sought the $2.4 million loan because of assurances from Dean and Andrews that his ideas for redeveloping Georgia Avenue had the authority’s support.

That suit also was dismissed. But as legal claims went back and forth, nothing happened on Georgia Avenue.

“Alternate universes”

Turner Field’s neighbors hope that as the Braves negotiate their lease with the city and as Invest Atlanta convinces developers to reimagine those parking lots, they too will be part of the discussions. They are not optimistic. “The first I heard about Invest Atlanta’s project was when I read about it in the AJC,” said Micah Rowland, who chairs Neighborhood Planning Unit V, which includes the stadium neighborhoods.

Suzanne Mitchell, who lives four blocks from the Ted, eagerly read the coverage on AJC.com. Then she got to the reader comments. “I was horrified,” she told me. “Then angry. People were calling my neighborhood ‘the ghetto.’ Saying awful things.”

Talking with Mitchell at her kitchen table, her outrage is understandable. Her home, one of those built on the northern edge of Summerhill after the Olympics, is light and airy; sun floods in through transom windows, dapples the wooden floors, and glints on the stainless appliances.

When they were house hunting, Mitchell and her husband, David, drove through Summerhill and a woman waved at them from her front porch. “I knew I wanted to be in a neighborhood like this, with front porches and friendly people,” she said. They moved in, and twelve years later that friendly stranger is godmother to the Mitchells’ children.

Mitchell, who is president of the Organized Neighbors of Summerhill, said she realizes that to most, “stadium neighborhood” is synonymous with that desolate stretch of Georgia Avenue.

“We coexist in alternate universes,” she said of the year-round residents of Summerhill, the Braves organization, and the fans who descend on her community.

Photograph by Rebecca Burns

Photograph by Rebecca Burns

The residents of the stadium neighborhoods occupy alternate universes of their own. Some live in finely constructed houses in the north section of Summerhill or in Mechanicsville lofts within walking distance of Downtown. Others live in subsidized housing or cramped apartments. Some have careers in tech or law or architecture. Some work only during baseball season. In Peoplestown, more than half the adults are unemployed. At D.H. Stanton Elementary School in Peoplestown, 98 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch.

The ballpark doesn’t make life easy for anybody who lives here. It’s not just the traffic and the rowdy fans who urinate in the streets and leave behind mounds of trash. All the hardtops and highways create a heat island; in the summer it’s 12 degrees hotter near the stadium than in Atlanta’s suburbs. The parking lots cause massive water runoff; Peoplestown floods constantly. Braves fans complain about game-day traffic, but those idling cars contribute to real problems for people who live off Hank Aaron Drive; Fulton County’s Health District 6, which includes the stadium area, has the highest death rate from asthma, more than five times higher than Fulton’s lowest rate.

What most people—wealthy or poor, young or old—who live near Turner Field want more than anything is a grocery store. Like other impoverished sections of Atlanta, the stadium community is a “food desert,” where fresh, affordable groceries are impossible to find. Nor is there a single bank in the area. And no pharmacy. No hardware store. In Peoplestown there is not one licensed childcare provider. If you’re looking for a meal on the Summerhill/Peoplestown side of the freeway, here are your options: Fuwah Chinese Restaurant; Bullpen Rib House, tucked between the south exit of Turner Field and the Connector; and a Wendy’s on University Avenue.

“A man who delivered”

On the morning of Saturday, May 18, as John Elder drove east on I-20, his silver 2006 Town Car suddenly veered and crashed into the median wall. He was dead when police arrived. The Fulton County Medical Examiner’s autopsy report said heart problems may have caused him to lose control of the car. Elder was a month away from turning seventy-one.

One week later, every pew in the sanctuary at Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church was crowded, the balcony packed. Wreaths surrounded the pulpit and Elder’s casket; on this warm Memorial Day weekend, the scent of roses quickly filled the church. A woman wearing an old-school nurse’s uniform with a neat white cap hovered near the pulpit; when she spied a mourner overcome—by grief or heat—she rushed over to wave a fan. Many mourners wore Sunday finery or traditional all-white or all-black funeral attire, but others arrived in work clothes; an elderly woman in a long apron paused at the casket behind a girl in a sleek silk dress and a large hat. From his pew, Jimmie Greathouse, who first met Elder in 1971 and has worked at Easy Parking for the past few years, glanced at the coffin and then back down, his eyes red. “I can’t believe this,” he said.

Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard strode to the pulpit. Howard, who met Elder in the late 1980s representing him in a civil case, told this story: One evening, just around dinnertime, Elder stopped by the Howard home. On the Howards’ dining room table: frozen corn, the kind “from the Cascade Farmers Market, better known as Publix.” The next day Elder returned with “the biggest bushel of the freshest, most delicious corn.” From then on, Howard said, Elder became known in his household as “the man who delivered the corn.”

But, said Howard, “The truth is, John has been delivering corn to a whole lot of people. He’s been motivating, facilitating, he’s been hiring, and he’s been sharing. If John has delivered for you, can you please stand?”

About a third of the people rose from their seats. Mario Redding, who works at Easy Parking (and is not related to Frank Redding), shook his head gently as he stood. Greathouse cleared his throat.

No one disparages the man he eulogizes, but that didn’t deter Douglas Dean from talking about Elder’s reputation. “John was a liability sometimes,” Dean said, because he was misunderstood. “He wasn’t a politician. It was the little folks John wanted to give dignity. He wanted to see they were all right. John didn’t just bring corn by Paul Howard’s house. John fed a lot of folks in this city.”

Personal finances aren’t usually discussed at funerals, either, but speakers referenced Elder’s tax and loan troubles. Howard, the district attorney, vowed, “Everything that John owns, I believe ought to be there for John’s family. I want you to know I’m going to dedicate myself to make sure that happens.” The Reverend James H. Sims Jr. urged everyone who owed cash to the deceased to “pay up.”

As the choir belted “Going Up Yonder,” everyone swayed along as pallbearers carried the coffin down the aisle. Outside, congregants clustered on the church steps. George Trammell, Howard Johnson, and other members of the Booker T. Washington Class of 1960 recalled Elder’s prowess on the football field. The Easy Parking staff made their way to Greathouse’s van and headed down Westview Drive for the cemetery. I cut down Ralph David Abernathy, crossed under the expressway, and passed Elder’s buildings on Georgia Avenue. Fresh paint covered the latest graffiti.

“Bring it on”

Four days later, the Braves hosted Toronto. An hour before game time, about half the Easy Parking spots were claimed. “It’ll fill up after the game starts,” said Jimmie Greathouse. His wife, Shirley, was a college friend of Elder’s wife, Erma—“so close they were like cousins.” Greathouse and his family came to Atlanta from Detroit every summer and stayed with the Elders. An Air Force vet turned corrections officer, Greathouse retired in 2005 and moved to Atlanta a couple of years ago, and shortly afterward agreed to help out with Easy Parking. His background comes in handy; the skills needed to keep tailgaters in line aren’t that different from overseeing guards and prisoners.

From a folding chair under the great water oak, Greathouse surveyed Easy Parking’s “upper level,” which stretches out from a high point on Fraser Street across several lots down along Georgia Avenue. Mario Redding, just promoted to deputy manager, directed drivers as they pulled in: older fans up front, close to the ballpark, young folks to the rear, where their loud car radios and pre-gaming wouldn’t cause a fuss. Greathouse took a call: “Yeah, I’ve got your spot.” His phone is filled with customer numbers; they return game after game, year after year, to favorite spots.

Greathouse said he and Elder used to sit under this tree and talk for hours, “especially about how we came up as kids.” Elder, Greathouse said, “started with nothing” and never forgot his roots. Greathouse gestured toward an apartment building beyond the lot. “I’m part of an area like this; I worked myself out of the ghetto. So did John.” And, he said, they both believe in passing on what they’ve learned—for instance, helping young men like Mario Redding work their way up.

In trying to figure out why the area around Turner Field languishes, you could label John Elder a villain—a man who cared more about making money a few months of the year than creating permanent change. Or you could, like the hundreds of mourners at his funeral, consider him a benefactor, someone who hired the people who live in the shadow of the stadium, a folk hero who understood their lives better than anyone in City Hall or the Braves’ front office.

At Easy Parking’s “lower level,” where the land slopes down to meet Hank Aaron Drive, Frank Redding held court. This is the VIP area; a few weeks ago the statehouse Republicans reserved the whole place. The lieutenant governor parks here, said Redding. The big tree covers this level, too, and as Redding sat in its shade and spoke, tears trickled from behind his mirrored sunglasses. “I’m a grown man, a Vietnam veteran. But I weep for John Elder,” he said.

What will happen to Elder’s property, and thus what will happen to the area around Turner Field, is still unknown. No matter what, “we’ll be here,” Redding said. “If there’s going to be a change, we’re going to be part of it. I say: Bring it on.”

The story originally appeared in our July 2013 issue

Update: The next chapter

In November 2013, the Atlanta Braves announced plans to relocate to Cobb County, building a new stadium and leaving Turner Field after their lease expires in 2016.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)