I was away at photography school, Creative Circus in Atlanta, when my mom started to suspect something was wrong with my dad. It wasn’t one moment, more like a series of subtle changes in his behavior. He was just a little off. Suddenly he was second-guessing decisions he made at the hospital in Sandersville, Georgia, where he’d been a surgeon for 26 years. It was as if he’d lost his confidence in his own mind. His temper was shorter. One day he decided he didn’t have enough room for his clothes, and he told my mom to get her “shit out of the closet.” A couple of times, he literally beat his head against the wall. He had been taking various medications for depression since I was a kid, so we thought maybe an errant prescription was to blame. My mom wondered if he might be drinking again. But she finally took him to a neurologist, who looked at an MRI and told her that my dad had frontotemporal dementia, a rare brain-cell degeneration related to Alzheimer’s.

I have always worshiped my father, but he wasn’t perfect. My earliest memories of him contain the rattle of a pull-tab in an empty Budweiser can. At night, when he got off working crazy hours at the hospital, he’d drink a red cooler full of beer—but never when he was on call. And he was never abusive to me. The beer just seemed to slow him down. I thought it was normal, just what hard-working guys did, until one night when I was in sixth grade and heard my parents get into an argument over his drinking. Scared, I ran away from home—four blocks down the street. My mom found me hiding behind a tree and told me that my dad was an alcoholic. He drank in the van all the way to rehab in Smyrna.

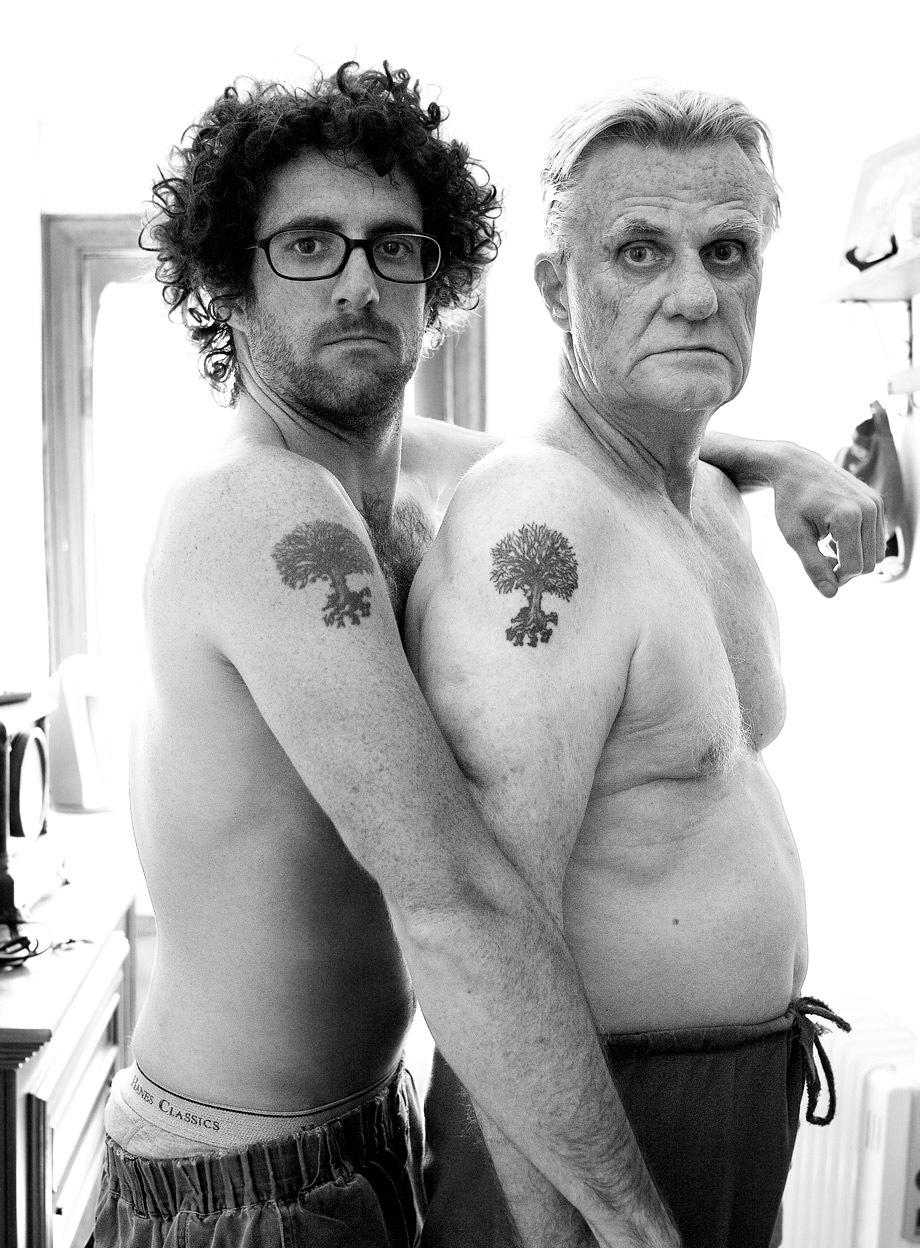

After he got out of rehab, my dad was a different man. Happier. Clearer. He seemed interested in things other than work, in the things that interested me. We’d talk about music I was listening to. He still loves R.E.M. One Easter when I was much older, he and I skipped church and got matching tattoos of the tree from the album cover of Goodie Mob’s Still Standing. The roots of my tree spell out W-A-R-D-I-I; his, W-A-R-D-I—John Robert Ward I.

While in rehab, my dad was diagnosed with depression. My family was always very open about it; we always talked about what was going on with our minds. Other families in our small town who were scandalized by words like alcoholism and depression never seemed to understand. I remember some kid at a football game saying something about my dad’s illness, and I beat his ass. My family never glossed over mental illness because hiding it somehow seemed to make it worse.

When my mom called me about Dad’s diagnosis in 2007, I was in the studio for a documentary photography class. I immediately thought that I needed to quit school and move back to Sandersville to take care of him. Dad didn’t like that at all. Absolutely not! It will severely let me down. He had come out of retirement and gone back to surgery to help pay for my tuition. He told me photography school was a path to discovering who I am and who I’m meant to be.

So as a project for that same documentary class, I started taking pictures of my dad. And from day one—snapping shots of him in his scrubs—he’s always been game. Anything to help me out, he says. Now it’s to the point where he asks why I’m not shooting this or where is my camera. I call the project “My Father Has Gifted Hands.”

Thing is, he was never very handy. I don’t think we had a tool in our house. The man has never even pumped his own gas. But he could take apart your body and put it back together. I still run into people in the local grocery store who tell me stories about how my dad fixed them, kept them alive. He had this gift.

My gift, I hope, is taking these pictures. It’s also a way for me to spend time with my dad. Nowadays, he sleeps in until one or two in the afternoon. He runs every day, two to three hours during the hottest part of the day. He stays up late watching TV or reading books about the Civil War. There are days when you wouldn’t even notice anything is wrong. There are others when he’ll momentarily forget where he’s supposed to go.

Thing is, my dad is going to be just fine—there just may be a day when he doesn’t recognize us. It’s going to be me, my mom, and the rest of the family who will suffer. I worry about my mom more than him. This whole thing is aging her. You can see her in the pictures, in the background, slightly out of focus. Caregivers are always there, day in, day out, slowly wearing down, but no one pays them much attention. People forget.

For me, these photos are my release, my way to express what we’re going through. Someday my dad will be gone. If I obsessively take these pictures, I’ll have captured days, moments, of this journey. —As told to Tony Rehagen

Want more articles like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for our LiveFitATL emails:

This article originally appeared in our July 2015 issue.