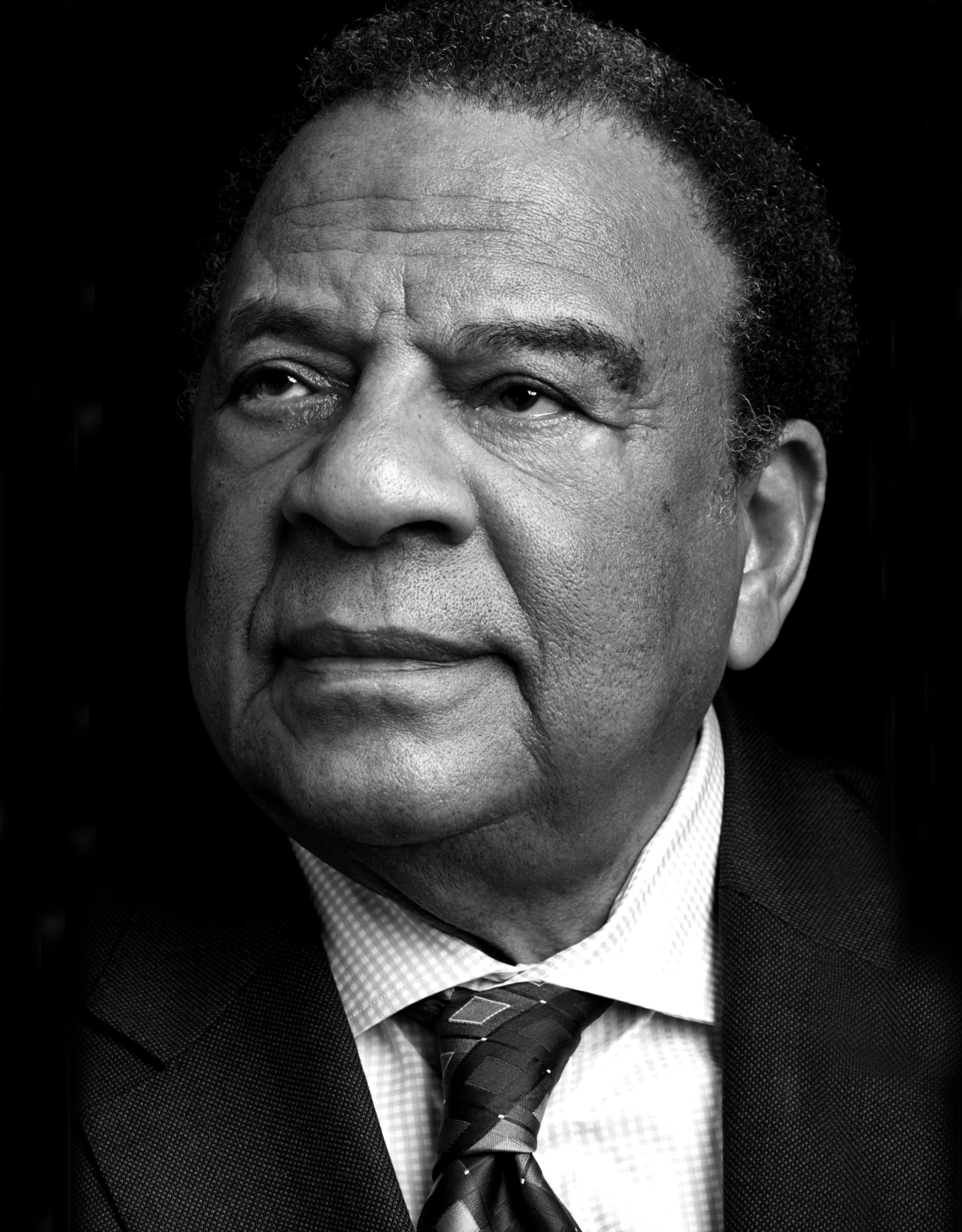

Photo courtesy of the Andrew J. Young Foundation

On June 3, the Andrew J. Young Foundation will present the second biennial Andrew J. Young International Leadership Awards at Philips Arena. Former Vice President Joe Biden, CNN commentator and author Van Jones, singer Akon, educator Ron Clark, and the Women’s March are all honorees this year.

The event will double as Ambassador Young’s 85th birthday celebration. The longtime politician and civil rights leader’s actual birthday was on March 12, but it takes some time to wrangle with the busy schedules of Usher, Jill Scott, Wyclef Jean, Estelle, and Anthony Brown, all of whom will will perform on Saturday. Black-ish star Anthony Anderson will emcee.

Young was born in New Orleans during the Great Depression and Jim Crow segregation. He graduated from Howard University in 1951, then earned a divinity degree from Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut. In 1955, he moved to Thomasville, Georgia, to serve Bethany Congregational Church as its pastor. He moved to Atlanta six years later to work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, becoming a close confidant to Martin Luther King Jr., and was instrumental in organizing voter registration and desegregation campaigns in the southeast.

Young went on to serve as a U.S. congressman and was the first black U.S. ambassador to the United Nations before he was elected as mayor of Atlanta from 1982 to 1990. With his foundation, Young is looking to promote education, economic justice, health, leadership, and human rights initiatives in the United States and Africa. We recently sat down with him to discuss his career—past, present, and future.

Where do you think we are now, in terms of civil rights?

We’re right there. We’ve made enormous progress on race, more than we admit—too much for most people. And that’s what’s making people insecure. If you look at television on a Monday night, you’d think this was a totally black nation. You look at football or basketball, and you wonder, “What happened to the white folks?” So a lot of people are uncomfortable with that. But that’s a transition. We’re seeing it level off.

But poverty is everywhere, and it has nothing to do with race. The problems in Columbus or Cincinnati are not due to race. [Atlanta] understands that we were a part of a global economy, and we are, frankly, the leader. We have 250 German companies here, and we have 660-something Japanese companies. And we have about 250 French companies, not counting the restaurants. And Korean businesses. I mean, everybody moved their businesses here because we went out and invited them. Atlanta is the kind of place where you can do anything anywhere in the world because of the airport. You can leave in the morning, do what you have to do, and come back that same night or the next day.

If you were mayor today, what would be your priority?

It has to be traffic. We actually had a traffic plan to avoid this. We had another outer perimeter scheduled for 65 miles from the center of town. I don’t know who didn’t want it, but once Sonny Perdue became governor, he sold all the land that we’d set aside. Somebody’s got to start over, but it would have been built by now.

Are you close with Kasim Reed?

I think I did the best I could with him and then got out of his way. We’re close, but we very seldom talk about his business. He didn’t talk with me about my business. He can ask me anything he wants to ask me. Kasim met me when he was 10 years old. He decided he wanted to be mayor because I slapped him on the head and said, “You got your fro together; I hope you got your brain and your mind together.”

Then I met him again when he was a college student. He was running for a seat on the board of trustees [at Howard University], and his platform was that the students were too privileged. He was challenging them to add $15 per quarter to the tuition to create their own student-run foundation to help students who were less fortunate. I said to him, “Damn, I wasn’t thinking like that when I was your age. You need to hurry up. If you can sell this to the Negroes, to be concerned about somebody else, you need to come on back to Atlanta and run for mayor. We’ll need a mayor like you in 20 years.” Exactly 20 years later, we elected him mayor.

What are you working on now?

There are a lot of things I’ve been dabbling in all my life that I’d like to see completed. Most of them revolve around ending poverty.

When I became mayor, the city was pretty much doing integration on its own. I didn’t have to worry about race. In Congress, we had ended the war in Vietnam, and so when I came here, I was focusing on poverty. When I was running for mayor, I said, “The only way we can keep the city growing is to become the next great international city.” That seemed crazy in 1981. Ronald Reagan was elected. There was no financial help from Washington. I said, “We don’t need help from Washington. We can find money all over the world. There’s a lot of money that doesn’t know what to do with itself.” The Dutch probably started it because they built the Ritz-Carlton downtown. In my first term, they probably invested over a billion dollars into this city. Maynard Jackson had built the new airport. People didn’t think that it was going to work. I said, “No, we’ve got to have an international terminal. We’ve got to bring in this international money.” I got Lufthansa signed up and then Japan Airlines and then KLM.

Now, I’ve discovered something called duckweed. We discovered that you could cook it, and it becomes the richest edible protein. We don’t know that it’s edible yet, we eat it and like it, and we are in the process of having it tested with the Department of Agriculture at the World Bank, using the historically black colleges to do all of the documentation. You can harvest half of it every day, and it will grow back the next day. It’s all over everywhere, it’s warm, and you take it for granted because you think of it as a nuisance.

Do you ever succumb to self-doubt?

No. Dr. King used to say, “It’s a 10-day nation. If you’re doing something new, the first 10 days, you’re wrong, you’re crazy. In the next 10 days, they’ll say, ‘Well, maybe there’s something to it.’ And in the third 10 days, they’ll say, ‘Well, obviously this is right.’”

And I don’t want anything for myself. God put everybody on earth for some purpose. There was something you could do that nobody else could do. You didn’t have to know what it was; you just do the best that you can one day at a time.

Looking back, what was your purpose?

I really wanted to go to New York. I had a job in New York, and I was going to run with the Pioneer Track Club. I was interested in the 1952 Olympics.

But there was a church in Alabama that had grown out of a college established in the 1890s to teach people to read and write right out of slavery. Somebody did something; they went out of their way to help. My minister told me, “Look, everybody wants to go to New York, but nobody wants to go to Marion, Alabama. If you don’t go to Alabama, this church will collapse, and there’s no telling what will happen.” I couldn’t say no to that little church because that’s the same kind of church that educated my parents and grandparents. That was the right thing to do.

I got there, and I met Jean [Young’s first wife]. Really and truly, if Martin had married any of the girls he was dating in college—and there were a whole lot—and if I had married any of the girls I was dating in college, you never would have heard my name or his. We met each other through Coretta and Jean, and that’s how it all happened.

Almost every black family has a story they seldom talk about. It almost always involves rape, murder, lynching, people robbing your property, or burning down your house. Coretta’s father had three businesses destroyed: a grocery store, a saw mill, and a logging company. There was just so much resentment of his success. And Jean’s family came out of the Civil War with an entire business operation. Her uncle owned a whole block with a grocery store, bakery, candy store, and shoe shop—like a mini-mall. In 1914 they took it from him somehow, and that left her grandfather and father with no jobs. Her grandfather committed suicide, her father became an alcoholic, and she grew up in the worst kind of situation you could expect as a teenager. But a Quaker couple came to teach them. They sent Coretta to Ohio to Antioch College, and Jean and her sisters went to Manchester University in Indiana.

That’s what builds character; that makes you want to make a difference in life.

What are your thoughts about the current White House administration, and do you have a relationship with it?

We went down to Mar-a-Lago for Maya Angelou’s 80th birthday with Oprah Winfrey. [Trump] was a perfect host. Because it was Maya’s birthday, we had a real religious ceremony, which he took a good part in. For me that says there’s always hope.

I haven’t figured out how to work with him. I don’t want to be used by him, but I do want to help. He might be more ready to deal with this enterprise zone I’ve been thinking about.

They’re building ships that are too big to survive. The ships that they’re going to be using in 10 years are too wide to fit through the harbors in Savannah, New York, or Miami. There’s not a single port along the East Coast that can handle the kind of ships that are going to be running the world. So I’m not thinking about a port in Savannah or in the Savannah River; I’m thinking of a port 20 miles offshore that would look like the Atlanta airport. Those concourses would be floating docks, and with three of them, we could handle six ships at a time.

If we do that, and get the engineers and the cities and planning together, we could sell a trillion dollars in tax-exempt municipal bonds. We can finance [Trump’s] infrastructure plan without taxpayer money. Now, we can do it. It’s not luck, and it’s not an accident. It’s just that you have a Congress that doesn’t understand the world.

Do you feel positive about the future?

It’s not a matter of how you feel.

I went with Martin Luther King Jr. to see President Johnson in 1964. He said that he was sorry, but there could not be a Voting Rights Act. He said, “I don’t have the power. Congress is not going to do this. There are very good, logical reasons why we shouldn’t have a Voting Rights Act.”

When we left, I asked Dr. King, “What are we going to do?”

“We’re going to get the president some power.”

“The hell you say? Where you going to get the power?’”

“I don’t know, but we’re going to get it.”

That was the 18th of December 1964. By March 1965, Lyndon Johnson was delivering his “We Shall Overcome” speech and introducing voting rights.

Now, how we got from there to there . . . we didn’t know how it was going to happen, but you do what you have to do, one day at a time, and it happens.

Tickets to June 3rd’s Andrew J. Young International Leadership Awards, ranging from $50 to $1,000, can be purchased at ajylead.com.