A bright banner hanging above the schoolhouse door reads: “Congratulations: Most Improved Test Scores.” And for Hope-Hill Elementary School on Boulevard, compliments are in order. The school’s rating on the state College and Career Ready Performance Index (CCRPI) rose 20 points—a 44 percent jump between 2013 and 2014, the biggest surge for any school in the Atlanta Public Schools system. This is all the more impressive considering that Hope-Hill, where 95 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch, was slated for closure a few years ago due to low performance and dropping attendance.

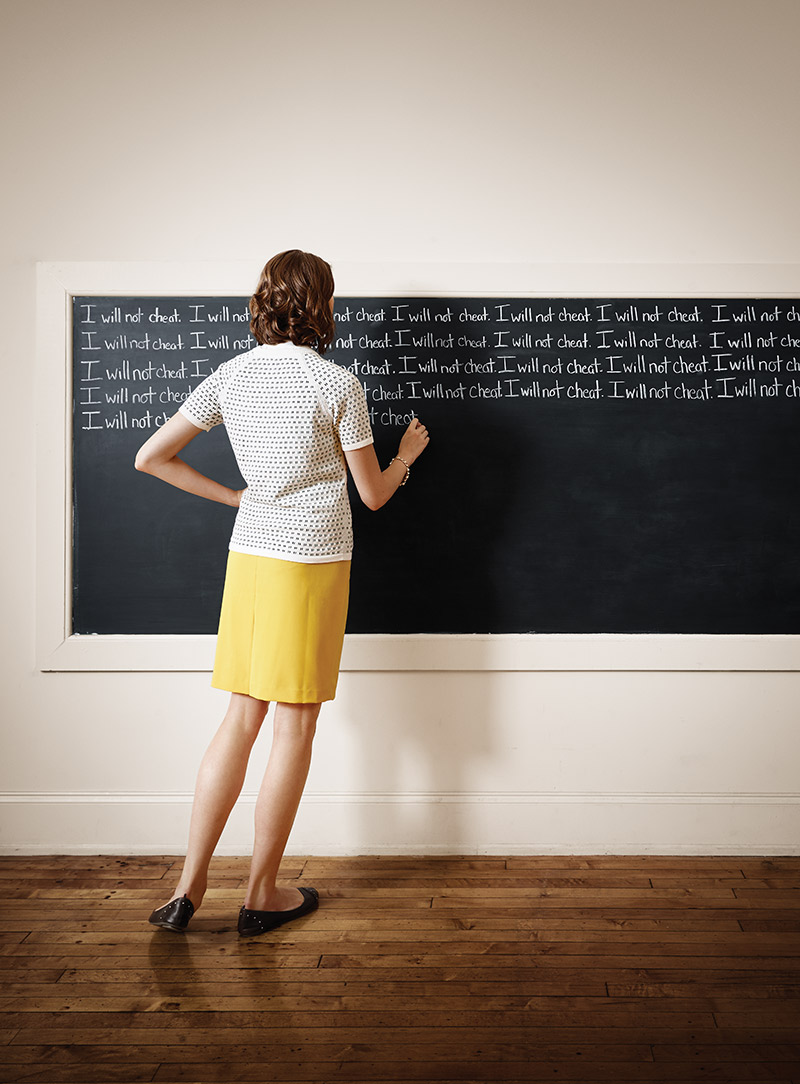

A decade ago, stellar turnarounds such as this earned APS national praise. But now—in the wake of a cheating scandal that resulted in a trial, convictions, and TV footage of former educators handcuffed and headed for jail—gains at APS seem to come with an asterisk: Are they too good to be true?

“It makes me sad that we even have to ask that question,” says Maureen Wheeler, who became Hope-Hill’s principal two years ago. “We have done a heavy lift in two years, but that thought is still looming out there.”

Wheeler implemented a school-wide improvement program focused on teacher training. She upended conventional classroom methods and now has teachers specialize by subject, which usually doesn’t happen until middle school. “It’s been a lot of hard work,” she says.

And though no misdeeds were reported at Hope-Hill during the cheating investigation, Wheeler proactively implemented strict protocols during testing periods. She removes herself from the testing environment so she won’t seem to be interfering. Test materials are monitored at all times. Everyone clears the building at 3 p.m. (Testimony by staff at schools where fraud happened revealed after-hours “cheating parties,” during which teachers gathered to erase and correct wrong answers on tests.)

At the macro level, APS still faces the shadow of the cheating debacle. Superintendent Meria Carstarphen took over last year, filling the position that had been vacated by Beverly Hall, who was indicted along with 34 subordinates but died of cancer before the trial’s end. Addressing the APS board in January while the trial was underway, Carstarphen said it was “no secret” that APS “has a tarnished reputation for its adult culture,” adding, “we are going to have to earn that back and establish a clear child-centered agenda.”

Carstarphen and the APS staff face a twofold challenge: implementing real improvements in a scandal-rocked system that underperforms most of the state, and finding ways to help students who were harmed by the systematic cheating of years past.

Photograph by Ben Rollins

To achieve the former, APS instituted ethics training programs—100 percent of staff had taken part by December 2014—and Carstarphen replaced teachers and principals. She might have to shuffle more staff: This summer the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that the principal of South Atlanta School of Law and Social Justice, a “theme” high school, faced allegations of falsifying more than 100 report cards, eliminating Fs from student transcripts. (The principal’s contract has not been renewed.)

“When recovering from a crisis, three things are essential: communicate, be transparent, and be visible,” says Barbara S. Gainey, a crisis communication expert and chair of the communication department at Kennesaw State University. On these measures, APS’s new regime flubbed the latest scandal; reportedly, the administration knew about the faked grades for almost a full academic year before the newspaper reported on them. After the news broke, Carstarphen dragged her heels talking to the AJC or other media. (She declined an interview request for this story, only forwarding statements through the APS press office.)

Such a lack of transparency in the wake of a new scandal could undermine APS’s efforts to rehabilitate itself after the old one. “While a crisis is something we tend to see as negative, it’s also an opportunity to do something positive, make changes that are needed, and talk about those changes. You can learn from your mistakes,” says Gainey.

APS is attempting to learn from the 2009 scandal. It commissioned an independent study by Georgia State University researchers, whose analysis demonstrated that more than half of the students in APS classes flagged for high numbers of test score erasures and corrections (i.e., signs of cheating) in the 2008–09 school year were still APS students in the fall of 2014. There was “robust evidence” that for those 3,728 students, cheating led to later problems with English and language arts, according to GSU professor Tim Sass, who headed the study. Negative effects of cheating on math tests were “mixed,” according to Sass and his team, whose analysis also revealed that teachers were more likely to correct tests by the less able students, compounding the chance that those students would fall behind. And teachers were most likely to cheat on tests by African American students.

APS began a “remediation” program in the 2009–10 school year, after test erasure cheating was first revealed. The program provided help to every student who scored low on that year’s tests, a system-wide effort that continued for a few more years, operating under the assumption that helping all struggling students would also benefit those who’d been “cheated.”

Future efforts will be more targeted. The GSU study spotlighted the students most likely to have been hurt by cheating—a cohort of seventh through 10th graders. APS is tailoring efforts to help that group, such as increasing evening and weekend tutoring and adding a dropout prevention program.

A fixation on testing and pressure to post ever higher scores spurred cheating in the first place. Students who “passed” tests and were promoted to higher grades without mastering course work or getting extra help experienced setbacks “equivalent to one to two times the difference between having a rookie teacher and a teacher with five years of experience,” according to the GSU researchers.

Billy Hungeling—chair of the Hope-Hill Foundation, which raises funds to support the school—says no one questions the progress the school has made, nor do they ignore how much further it has to go. “Cheating is not a concern I have heard,” he says. “But parents worry about the administration, APS system costs. They want the administration to get out of the way.”

Carstarphen has submitted a charter system application to the state, which would allow for more individual school autonomy. Meanwhile, Principal Wheeler says she’s thinking about the future, not past problems at APS. Her focus: improving daily instruction. While the school made gains, “our scores are not real strong,” she says. (Hope-Hill scored 63.2 points on the CCRPI assessment in 2014, while Mary Lin Elementary in Candler Park, two and a half miles away, scored 91.5.) “If we don’t focus on what happens in the classroom every day, the only ones we hurt are the kids,” Wheeler says.

Scorecard

Researchers at Georgia State University analyzed the results of APS classrooms with high levels of cheating in 2009 to track the ripple effect through fall 2014. What they learned about how cheating hurt students:

51%

of students in classes flagged for high erasure rates on the 2009 CRCT standardized tests were still enrolled in APS in fall 2014—5,888 students in total.

5%

of English/language arts tests in 2009 had more than 15 wrong-to-right erasures. For math, the rate was more than double—11 percent.

98%

of students with 10 or more wrong-to-right erasures were black (the overall black enrollment of APS is 75 percent).

7,064

APS students likely had at least one test score changed on the 2009 CRCT.

25%

of students considered “off track” for graduation from high school in 2014 had tests that had been corrected at least 10 times in 2009.

This article originally appeared in our August 2015 issue.