Oli Winward

In January 1888, a young man named Will Dockery rode on horseback from Hernando, Mississippi, just south of Memphis, to Cleveland, Mississippi, a small settlement 100 miles farther south on the Sunflower River. When he got to a spot between Cleveland and Ruleville, he saw a small piece of cleared land “as rich as cream” covered in blue cane. He bought some of that land, went into the lumber business for a short time, and then began to farm cotton. He struggled, like all who came before and after, but seven years after his arrival, he owned forty square miles of land bisected by the river. Most of it was uncultivated, but he called it Dockery Farms, envisioning a great plantation. By the 1920s Dockery Farms housed and employed more than 3,000 people and had all the amenities of a small town. When dictating his memories to his son, Joe Rice Dockery, he spoke with deep fondness of his friends, his fellow landowners, and his employees and said, “If you once drank out of the bayous you never left.”

Courtesy of Dockery Farms

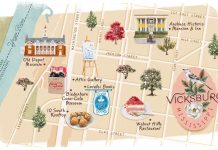

Today, the restored seed house and service station remain on that lonesome stretch of Highway 8 and work is scheduled to commence soon on the remaining structures, including the cotton gin and cotton shed, all spearheaded by the Dockery Foundation. Dockery Farms is now listed on the National Registry of Historic Places with National Significance.

The history of cotton farming and the tenacious and visionary spirit of men like Will Dockery and Joe Rice Dockery offers an aching glimpse into my own ancestry. My grandfather Ray Cash cleared 40 acres of gumbo soil in the Sunken Lands of Arkansas to farm cotton. My father, who worked in the fields himself from the age of eight, had no fond recollections of the backbreaking labor, but sweet memories of the resilient people who worked the land, and a deep love of the land itself—“every rock and tree,” as he wrote late in his life—just like Will Dockery.

The story of plantations like Dockery Farms is compelling, but it serves as a backdrop for an even larger narrative for a roots musician like myself: the history of the Delta blues, which seemed to come right out of that land that was like cream. The musicians of Dockery Farms didn’t register as anything special to the landowners in the 1920s and thirties; it was later generations who realized that an entire art form had birthed itself in those fields. Robert Johnson, the Father of the Blues, lived and died just down the road from Dockery Farms and most certainly was a visitor. Seminal blues musicians including Son House, Charlie Patton, Howlin’ Wolf, Pops Staples, and others lived and worked at Dockery. In the evenings, after a hard day’s work, the boardinghouses were turned into “frolicking houses,” and crowds of sharecroppers would drift over to hear these men play on their steel-stringed guitars. There was no electricity, so they put candles in front of mirrors to cast a glow across the fields.

Courtesy of Dockery Farms

This June, I went to Dockery Farms with my husband, John Leventhal, and my band. We set up in front of the seed house and performed a set of songs John and I had written after exploring that part of Mississippi. The album is called The River and The Thread, and it is rooted in and honors the music of the Delta—in spirit, in rhythm, and in imagery. Performing those songs at such a revered musical spot, a place that some call the Birthplace of the Blues, was an experience that shook me to my core. It humbled me, haunted me, and inspired me. I will carry that feeling and memory my whole life long.

Will Porteous, great-grandson of Will Dockery, has made it his life’s mission to preserve and honor this place and to bring music back to the farm. He and I both live in New York City, yet we carry the Delta in our blood. My concert was the first in what the Dockery Foundation hopes will be a series of many, many beautiful nights on a piece of land “like cream.” Because once you taste the bayous, once you hear the notes ring and fade across the Sunflower River, once you close your eyes and imagine the soft glow of mirrors lit by candles shimmering across the fields, a part of you will never leave, and you’ll take a little of the cream and the blues with you when you go.

One of the country’s preeminent singer/songwriters, Rosanne Cash has released fifteen albums, including her latest, The River and the Thread, which received three Grammy Awards earlier this year. She is also the author of four books including the best-selling memoir Composed. Her essays have appeared in the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Oxford-American, the Nation and many more publications.