Illustration by Lindsay Mound

Someday, perhaps as soon as November 6, a Democrat will win a statewide office in Georgia. It’s a statistical inevitability as the state continues to diversify. People of color now make up 40 percent of the state’s population, compared to 30 percent just two decades ago. Credit at least two factors. From 2013 to 2015, the average birth rates among blacks and Latinos were higher compared to whites—5 and 43 percent higher, respectively. Then, there’s the diversity of new arrivals to the state; roughly one out of every 10 Georgia residents is foreign-born, accounting for 5 percent of metro Atlanta’s population growth from 2015 to 2016.

Of course, not all whites vote Republican, and not all people of color vote Democratic. But race remains a reliable predictor of voting patterns, at least when it comes to blacks and whites. Four years ago, when Nathan Deal ran for reelection against Jason Carter, the incumbent governor captured three of every four white votes. And among black voters, according to exit polls, Carter won nine out of 10. Latino voters, though, were more evenly split between the two parties; in the 2014 election, 47 percent favored Deal.

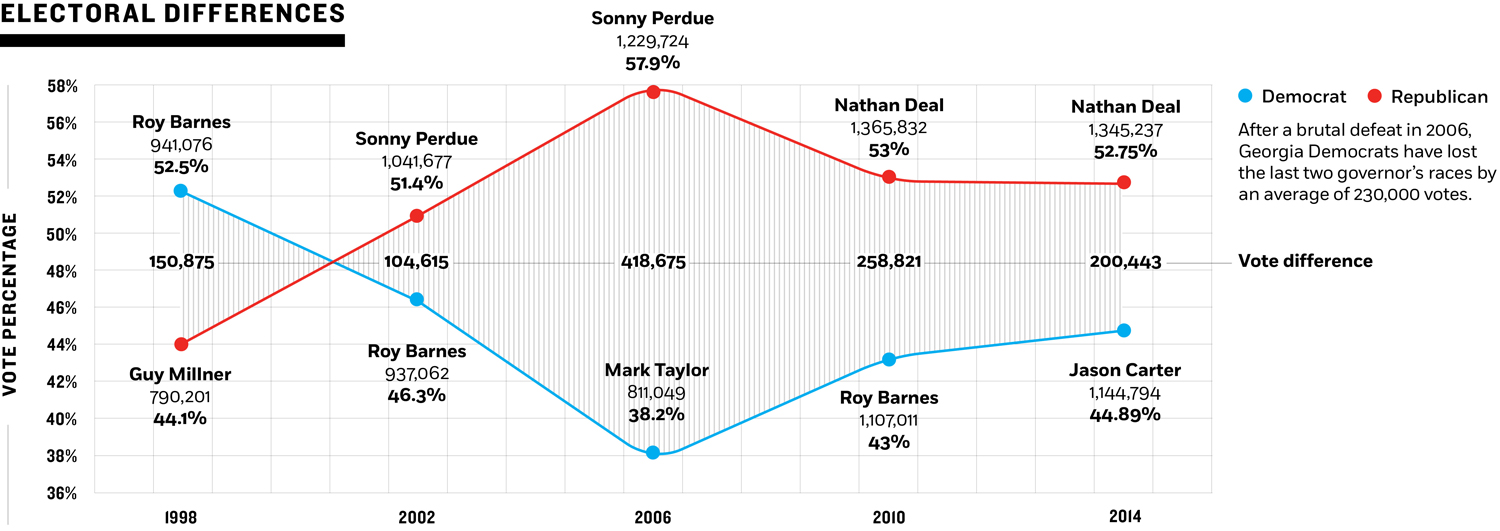

Deal won the 2014 campaign by eight points over Carter: not a landslide, but a comfortable margin in a state where 50 percent of registered voters went to the polls. However, the electorate is changing. Eight years ago, roughly 60 percent of the state’s registered voters were white, while today, only 54 percent identify as such. In 2014, Deal’s margin of victory was 200,443 votes. For Stacey Abrams—campaigning to become the first-ever black female governor in the United States and the first Democrat to win a Georgia governor’s race in 20 years—the only path to victory over Brian Kemp involves finding voters to close the gap that Carter could not.

So, where is she looking for them? First, in places like south DeKalb, where, on a recent Saturday, campaign volunteers went door to door. Black women in Georgia are the Democrats’ largest voting block and vote more reliably than any other demographic, says Andra Gillespie, a political science professor at Emory University. Abrams will need to fortify that base, while also reaching out to the young, the newly registered, and other voters of color, who don’t typically turn out for midterms. A mother of one who answered her door when Abrams volunteers knocked and identified herself as Courtney is a perfect example. She was not familiar with Abrams, but within three minutes of hearing about Abrams’s plans to expand Medicaid and get low-income Georgians on health insurance, she pledged her vote.

“She needs women in general. She has to make big inroads into metro counties, suburban women, and with moderate women.”

Of course, Abrams, who moved to DeKalb County from Mississippi when she was 16 and became state House Democratic leader at 34, must look beyond metro Atlanta—to the diversifying exurbs, other urban areas, and rural Georgia. In towns such as Dalton, she pledged to continue the criminal justice reform efforts begun under Deal. For Abrams, whose brother is a convicted felon, the stump speech takes on personal dimensions. In Macon, she pitched programs making capital available to small-business owners. In addition to expanding Medicaid, she wants to increase broadband connectivity to parts of the state still reliant on dial-up. Campaign offices in Sumter, Hinesville, and Albany, among other places, provide a base for outreach efforts.

There are 6.2 million registered voters in Georgia. The Abrams campaign assumes nearly 2.9 million of them are likely Democrats—but only a third voted in the last gubernatorial election. The Abrams campaign also estimates that among the state’s “soft” Democrats, moderates, and disaffected Republicans, between 80,000 and 180,000 could be coaxed her way, allowing Democrats to close an approximately 230,000 vote gap they’ve seen in the past two statewide elections.

In late July, the New York Times cast the Abrams-Kemp race as a battle between the far-right and far-left; the political middle, it wrote, is “all but abandoned.” But Abrams’s platform belies that facile narrative. Notwithstanding her calls for gun-control legislation and a proposal to remove the carvings of Confederate generals from Stone Mountain after a white-supremacist protest in Charlottesville, Abrams has consistently championed Democratic issues that would presumably also appeal to more centrist voters: Expanding Medicaid, she argues, would help combat the opioid epidemic and prevent rural hospitals from shutting down; universal pre-K would result in stronger academic performance; and increasing state funding for transit systems would benefit everything from MARTA rail to Dooly County’s nonemergency medical-transit service.

Five years ago, Abrams founded (and left, prior to the campaign) the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan nonprofit whose mission was to get more young people, people of color, and especially black women, registered to vote, mobilizing, and advocating. Black women are a mainstay of what Steve Phillips, a San Francisco–based political consultant, calls the “new American majority.” The future of the Democrats, he argues, is less in winning back white, working class voters than in people of color, unmarried women, and young people.

In an echo of the 2008 Obama campaign, Abrams and supporters have launched a multiracial coalition of progressive advocates, plus volunteers new to politics, to make inroads with newer, first-time, or marginalized voters in the form of roundtable talks with the candidate, meet and greets, and door knocking. Volunteers like Dr. Opal Ware, a 76-year-old get-out-the-vote expert who trained with Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-California), hand out voter registration applications to strangers they meet.

Any strategy based on bringing out infrequent or first-time voters is labor- and cash-intensive. Phillips has estimated that Abrams will need $10 million to inspire the “previously uninspired voters of color required to close the gap in Georgia.” That sum is $3 million more than what Carter raised in his unsuccessful run against Deal. As of her June filing disclosure, Abrams had raised $6 million—the bulk from donors giving less than $100—and had $1.5 million on hand. Though Trump’s approval among state Democrats is in the single digits, he enjoys overwhelming support, north of 80 percent, among its Republicans. The outcome of the Abrams-Kemp race will likely be as much a referendum on the president as it is a battle for Georgia’s political future.

But if Trump comes here to campaign, expect heavy hitters to stump for Abrams: Michelle Obama, Joe Biden, perhaps even Barack Obama. The unquantifiable element in this campaign is excitement—and whether a national blue wave could ripple to Georgia. “It’s the battle of the bases,” says Kerwin Swint, a political science professor at Kennesaw State University. “She needs women in general. She has to make big inroads into metro counties, suburban women, and with moderate women. That could get her close if everything else goes right.”

This article appears in our October 2018 issue.