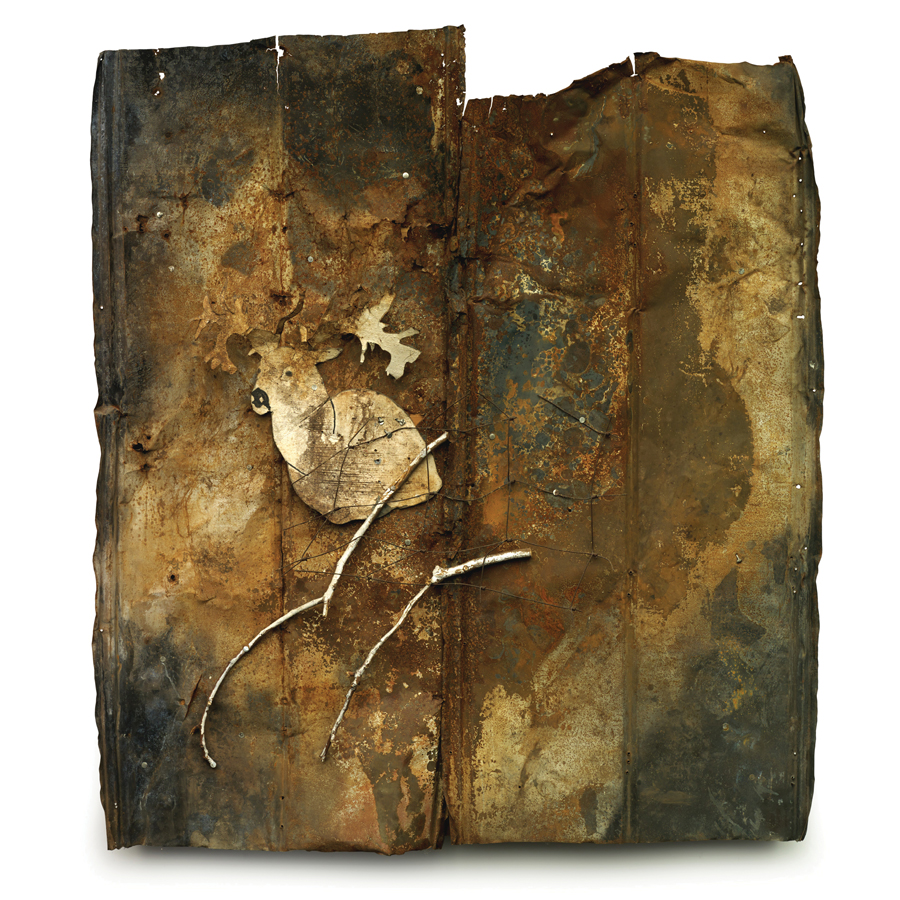

Of the more than 50 works on view at the High Museum of Art’s new retrospective exhibition, Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett, the one that resonates most with curator Katherine Jentleson is an assemblage called Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die. For Jentleson, the work is key to understanding Lockett, a little-known self-taught artist who used found materials and barn metal scraps to create pieces about everything from the Holocaust to his own experience as a black man in the post–civil rights era South. (He died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1998 at age 32.) She points to the presence of a confined deer, an avatar commonly used by Lockett to symbolize vulnerability, as well as the intricate metal work—no easy feat for the artist, whose small physical stature prevented him from taking one of the many steel industry jobs in his hometown of Bessemer, Alabama. She also loves the piece’s title. “It gives you the sense that, even though Lockett can’t be here to see how much his work is now celebrated, he’s very much still with us, as is his legacy.”

Photograph by William S. Arnett

Preserving—and putting a spotlight on—this legacy, and that of other so-called “outsider” artists, has been a priority for the High for more than 20 years. In 1994 it became the first general museum in North America to have a full-time folk and self-taught art curator; Jentleson, 32, is the first to hold the now-endowed position following a $2.5 million gift from Merrie and Dan Boone in 2014. “Self-taught art has a history that’s largely been neglected,” she says. “It’s really important for me to remind people—or make them aware—of the significance of these artists.”

Since she arrived in September 2015, Jentleson has made 78 new acquisitions; rearranged the museum’s existing gallery of works by Nellie Mae Rowe, the late Vinings-based self-taught artist; and presented three shows, including the Lockett retrospective. “Many people don’t even know the High has these incredible monographic collections of self-taught artists like Rowe, Bill Traylor, or Howard Finster; I’m excited to highlight them because they really distinguish us,” Jentleson says of the museum’s long history in the field.

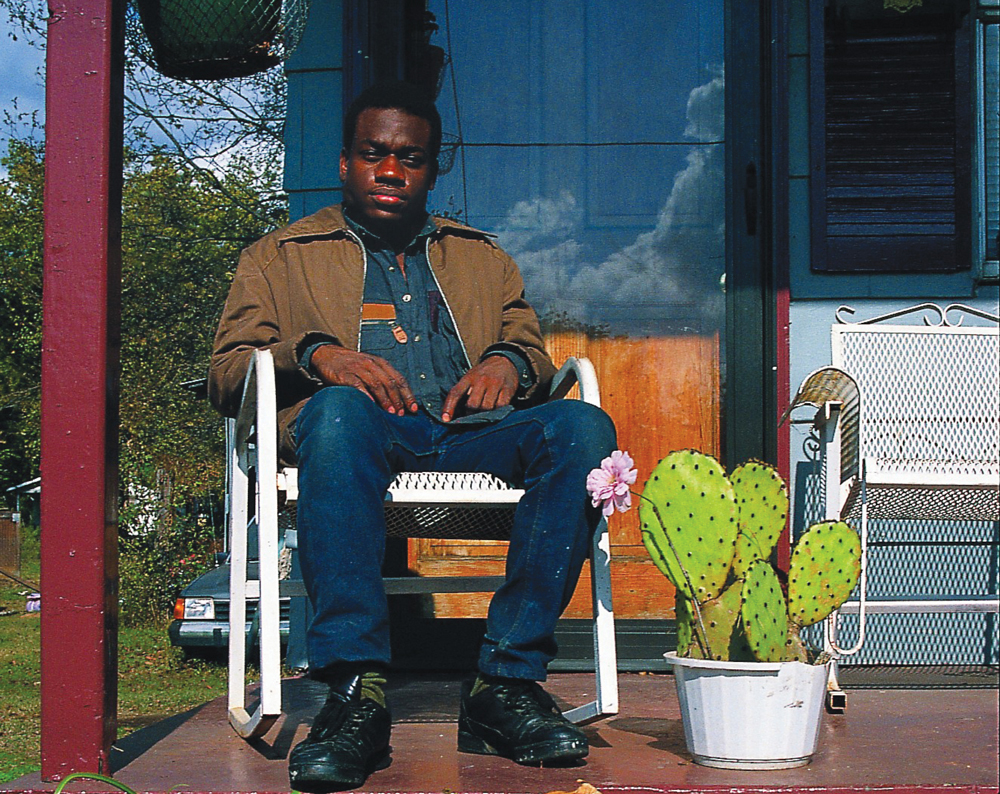

In the coming years, Jentleson also wants her exhibitions to incorporate more of a sense of place. Fever Within is accompanied by a sculpture exhibition, Forging Connections, which showcases the works of Lockett’s Alabama contemporaries, including his cousin Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley. “The idea is to show that it wasn’t just Lockett. There’s a whole movement engaged with the aesthetics of found, discarded materials to make art—and tell our stories.”

This article originally appeared in our October 2016 issue.