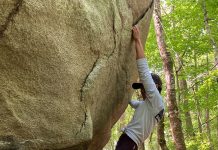

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Hey, climbers. Reminder that the gym closes in 15 minutes. It’s a Wednesday night, and Stone Summit Climbing and Fitness Center is crowded. The P.A. announcement is barely audible over the chatter filling the gym. “You better be watching this,” Michael Breed shouts down to his climbing partner from halfway up the wall.

“He never gets tired of that joke.” Gene Whitehead’s tone is exasperated, but a slight smile betrays his amusement. The punchline? The Navy veteran lost his vision more than a decade ago. A few seconds later, Breed lunges for the next handhold—and grabs it—but can’t hang on. With a frustrated groan, he slips off the wall. The safety rope catches his fall after only a few feet, and he slowly lowers down with a rueful smile. Gravity isn’t the only thing working against him: Six years ago, a ruptured brain aneurysm reduced Breed’s ability to coordinate his body. Life isn’t fair. It turns out rock climbing isn’t either.

Both men are longtime members of the Adaptive Climbing Clinic at Stone Summit, a gym in Embry Hills. Once a week, the volunteer-driven clinic offers climbers with physical disabilities the resources and equipment they need to participate. It is, unfortunately, a rare opportunity. Despite the recent boom in the sport’s popularity, lack of representation and support infrastructure remain daunting obstacles for people like Breed and Whitehead.

Certainly, the image of the archetypal climber—perfectly fit, equipped with Herculean upper-body strength—can discourage even nondisabled newcomers. “For people who have never been rock climbing, the first thing they always say is, I’m not strong enough,” explained Wes Whitaker, the cochair of the Atlanta chapter of the American Alpine Club, a nonprofit dedicated to ensuring both opportunities for climbers and sustainability of the sport in outdoor spaces. “They picture this muscular man hanging from an insane overhang, and that’s the first roadblock they have to overcome.”

For disabled climbers, though, a climbing gym can look forbidding. “The mental barrier is exponentially greater for someone with a physical disability,” said Eric Gray, the founder and executive director of Catalyst Sports, which runs the Adaptive Climbing Clinic. “Everyone on the wall has full function. And they have people saying, you shouldn’t do that or you can’t do that.” Catalyst is a nonprofit acting across the Southeast that helps folks with disabilities participate in adventure sports like mountain biking, kayaking, and climbing.

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Since its inception in 2013, Catalyst’s Adaptive Climbing Clinic has proven to be popular and powerful. Before he lost his vision, Whitehead was an avid mountain biker. “I miss the independence of it,” he said. “There’s a lot more camaraderie in climbing, though.” On the ground, Whitehead relies on a partner to guide him through the gym to the start of a route and to check the knots in his safety rope. On the wall, he regains the independence he relished on his bike. “Even for a sighted person, it’s just a rope between you and the ground,” he said. “That’s no different for me. You’re on your own on the wall, and you’re going to have to figure it out.”

For the clinic’s climbers, figuring it out means finding creative strategies to compensate for their disabilities. For example, the disease that took Whitehead’s eyesight has no effect on his motor control. By sweeping one hand in an arc across the wall above him—“I’m rainbowing it,” he announced—he finds the next hold and pulls himself up.

Climbers with cerebral palsy or paraplegia require more strategic adjustments. For example, wheelchair users need specialized equipment like the Wellman harness, an apparatus designed by a paraplegic climber. The contraption takes 20 minutes and two trained volunteers to set up. Tonight, Atlanta’s group has four climbers who use wheelchairs and one Wellman harness. In the span of a two-hour session, each climber uses the harness just once or twice.

“It’s nowhere near, yet, where it needs to be to really change the sport’s accessibility issues,” said Gillian Sharp, the clinic’s director, who holds one of only two paid positions at Catalyst. But it’s a step in the right direction: Even one Wellman harness is more than most gyms offer. The harness costs close to $600—pricey, but not prohibitive. Still, most gyms don’t own one. Despite variations in location, size, and revenue, climbing gyms have one thing in common: They often lack the necessary gear, training, and staffing to offer programs for individuals with disabilities. “It’s not that gyms don’t want it; it just doesn’t make money,” explained Mark “Huck” Huckeba, Catalyst’s climbing coach. “It’s not practical for them yet.”

To maintain Atlanta’s program, Sharp relies on the community. “We’re almost entirely volunteer-driven, which is really one of our assets,” she said. The preferable volunteer-to-climber ratio is one-to-one, but they sometimes need three-to-one to use certain equipment. On a recent night, volunteers were in short supply. Noticing their predicament, a few nearby climbers jogged over to help. Within a few minutes, the first climber was up on the wall.

After a few climbs, Breed—who is gradually recovering from the ruptured aneurysm but still copes with visual and processing issues—lent a hand, too. In his tenure as a climber, he’s achieved a lot, including a 900-foot multipitch climb called “The Daddy” in North Carolina last year. Still, moments like these mean the most to him: “Watching someone else get to the top of a wall,” he trailed off, drumming his fingers against his leg as he searched for the words. “I get more accomplishment from that than from climbing myself.”

This article appears in our January 2023 issue.