Photograph by Max Blau

In the spring of 2017, as firefighters doused the flames that had consumed Interstate 85, Atlanta first met Basil Eleby. Newspapers ran his mugshot, while TV news aired footage of his perp walk outside the Fulton County Jail. The 39-year-old Atlanta native, who had spent his days sleeping in a car and struggling with drug addiction, faced charges in connection with the fire that could have kept him in prison until he was in his sixties. But the media frenzy spurred a team of civil rights attorneys to represent Eleby pro bono. And they ultimately brokered a deal with prosecutors: Eleby’s charges would be dropped if he completed a two-year behavioral health court program.

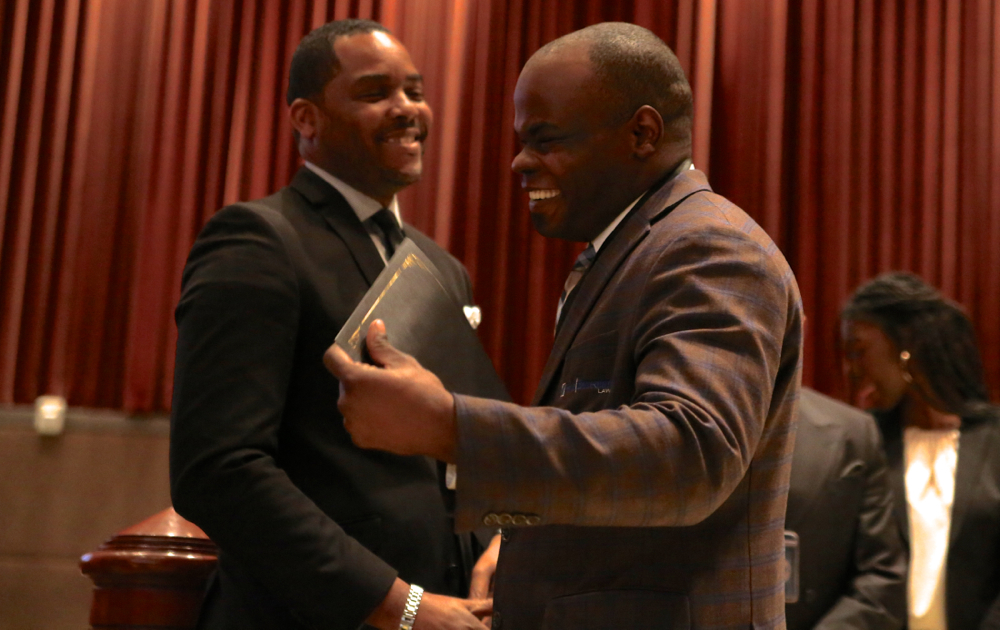

On Friday morning, in the Fulton Government Center, more than 100 people saw Eleby’s mugshot once again. But they weren’t simply presented with an image from his past—it was a reminder of how far he’d come. For on the other side of the room, they could see the 42-year-old—sharply dressed in a brown-plaid suit, with a trimmed soul patch—smiling widely and laughing with his attorneys. Eleby was not only relieved to see the charges dismissed, but also the fact his court-mandated program has led to over two years of sobriety.

“I feel like a new person—a person that’s accomplished something,” Eleby told me afterwards. “I’ve never accomplished nothing, or graduated from anything.”

Photograph by Max Blau

Nine months after the fire was extinguished, I started following Eleby for an Atlanta feature that focused on the rare opportunity he’d received to rebuild his life from the ashes of the fire. Eleby had gotten off to a rough start: At the time, he was struggling from a recent relapse, and overwhelmed by the work long-term sobriety would entail. As we drove around Atlanta, through the west side neighborhoods of his childhood, he described the trauma he’d faced growing up, which he said forced him to become self-reliant and, at times, self-destructive. Drugs helped numb the pain from an early heartbreak. “The cycle just started, man,” he described in a video played at his behavioral health court program graduation. “My goal was to numb myself of the pain of being depressed and being hurt.”

With the support of his lawyers—along with a small army of pastors and advocates—Eleby learned to be resilient. He rode the train to 12-step meetings, showed up to court hearings, and worked a part-time job at his lawyer’s office. He stumbled at times, too. One day in 2018, Eleby was frustrated over losing his phone, which caused a delay in paying off the fees needed to reinstate his driver’s license. Faced with those setbacks, he did not fall back into using drugs or alcohol. Instead, he persevered. As he strung together days of sobriety, he focused on his long-term goals: a bank account, a truck, his own apartment, and a girlfriend who was also drug-free.

“He was conditioned to not be forthcoming, living in a car for as long as he had,” said Derrick Rice, pastor at the Sankofa United Church of Christ, one of the key people who helped Eleby after the fire. “Once he realized we were serious about establishing a relationship, his approach became different. Basil is more genuinely accountable.”

“He was conditioned to not be forthcoming, living in a car for as long as he had,” said Derrick Rice, pastor at the Sankofa United Church of Christ, one of the key people who helped Eleby after the fire. “Once he realized we were serious about establishing a relationship, his approach became different. Basil is more genuinely accountable.”

Nearly three years after the fire, and after untold therapy sessions and recovery meetings, Eleby heard his name called out Friday by Rebecca Rieder, a Fulton County Superior Court Judge who oversees the accountability court. With his head held high, Eleby walked across the floor of the government center’s assembly hall, received a medal for his participation, and hugged the judge. Afterwards, a small gaggle TV reporters peppered Eleby with questions about the day of the fire. Eleby kept his cool, calmly maintaining his innocence, as he’s done since the day of the fire.

Photograph by Max Blau

When I asked Eleby what he’d learned about himself through his recovery, he told me that he’s focused on his “emotional growth” without the presence of drugs in his life. “I’m still learning who I am,” he told me. “When you start doing drugs at age 21, that’s when you stop the growth process. Sometimes, I feel like I’m 21 again, even though I’m 42. I’m growing now.”

Today, Eleby will start a full-time job at a bottling warehouse owned by CKS Packaging, where he’s expected to make at least $12 an hour, according to Phil Hunter, executive director of Georgia Works, who helped secure the position. As Eleby has achieved more stability in his life, he has started to check off those goals. He opened a bank account. And he started saving for an apartment of his own. His lawyers have raised $2,500 to purchase Eleby a 1994 Lexus, in hopes of shortening his commute, and are continuing to ask for donations to get him an apartment.

After the graduation ceremony ended, Eleby pulled something out of his wallet and handed it to me. It was his driver’s license. For him, it was more than just see a piece of plastic with his address on it. It was a reminder of how far he’d come, and how far he could go.