Keith Haring, From the series Apocalypse, 1988, Silkscreen, Edition of 90, 38 x 38 inches, each Courtesy of the Keith Haring Foundation, © Keith Haring Foundation, Photo courtesy of Keith Haring Foundation

While viewing works by Keith Haring in New York a decade ago, Rock Hushka was shocked to see no reference to the artist’s death from AIDS-related complications. “If you’re going to understand this artwork, you have to understand its relation to the AIDS epidemic,” says Hushka, chief curator of the Tacoma Art Museum. “Once you take that awareness out, the context is lost.” In response, Hushka and a co-curator spent 10 years putting together Art AIDS America, a traveling exhibition of 100-plus works that stops at Kennesaw’s Zuckerman Museum of Art this month.

Taken together, the pieces show the mark left by HIV and AIDS on American artists and their work, from 1981 through 2015. Among those on display: documentary photographer Nan Goldin’s images of her friends with the disease; one of Haring’s Altarpiece sculptures, his last works; and Sweet Williams, a painting made by Kennesaw professor Robert Sherer using HIV-positive blood. The exhibition also includes contemporary statistics on HIV and AIDS—Atlanta has the fifth-highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the country—and educational programming. “For me, [the exhibition] means that all of that shouting from the rooftops . . . finally someone heard it,” Sherer says.

Sherer came of age during the AIDS epidemic, and in the late 1990s, he began tackling the subject in a series of paintings made using blood—a method that he stumbled upon by accident after cutting himself in his studio, but which later became his signature. Today, he has created hundreds of these paintings, for example, using the blood of HIV-positive friends to paint roses. The striking nature of the paintings—delicate imagery composed of blood—has made Sherer one of the more influential contemporary artists commenting on the epidemic through his work.

Robert Sherer, Sweet Williams, 2013

Describe your personal experience with the AIDS epidemic.

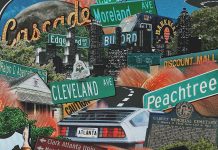

In the early 1980s, Atlanta was a really heady place, with thriving art, rock, punk music scenes. An entire generation of gay guys all came out in my freshman year at Atlanta College of Art in 1979. Then they started getting sick. The dumb luck of it all . . . it [was] when the AIDS crisis first happened. I turned into a total art nerd and stayed home and painted, so I didn’t get [infected]. Art literally saved my life . . . AIDS had a really profound effect on my generation, being a young gay man coming out when you’re 18 or 19 years old. It wiped out my generation of friends.

What inspired you to begin making art about AIDS?

I had tried throughout the years to address the HIV/AIDS issue. Most of the time, I was just so angry that the art I made looked like agitational propaganda. I finally reached a point where I just couldn’t say anything. [Then] I started playing with blood paintings. [After the accident] I grabbed a pencil jar and capped it over the wound. When I woke up the next day, there was that jar of blood. I am not a weirdo, but I thought, ‘This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.’ At the time, the works weren’t HIV/AIDS–related; I didn’t make the connection. I was painting roses, thorny roses, and hearts. Teresa Reeves [now the Zuckerman’s curatorial director] saw them and was like, “Oh my god, Robert. These are really profound and making these profound statements about HIV.” They got all the stuff that was pent up in me out.

How difficult is it to paint with blood?

Blood is utterly unforgiving: You can’t erase it. You can’t paint over it. Whatever mark you make, you’re stuck with it. So I have to make sure that I work out all of the pictorial logistics. I create elaborate drawings to work things out before I paint.

What was your reaction when you heard you had been selected for Art AIDS America?

I was completely shocked. I kept wondering when was there going to be a giant traveling museum show on this topic, so I jumped on it. Some people got tired of hearing AIDS, AIDS, AIDS all the time, and other people thought that because there were medications, it was cured.

What impact do you hope this exhibition has?

Since we live in a world where everyone forgets history rather quickly, I hope it educates the younger generation that there was an entire generation that was decimated. It’s not something I am over now, and I am never going to get over it . . . For me it would mean that all of that shouting from the rooftops, that finally someone heard it.

On the calendar: The Southeastern premiere of this exhibition runs February 20 through May 22 at the Zuckerman Museum.

This article originally appeared in our February 2016 issue under the headline “Crisis in Culture.”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)