Photograph by Simon Upton; Illustration by Mekel/The Jacky Winter Group

I see design in a very specific way. My personal preference is for spaces that are spare yet luxurious—unique, with forceful identities. I love interiors that captivate the senses and transport the viewer with a bit of wonderment.

I believe that my role as an interior designer is to command and fulfill the eye, not provide it with endless distractions. To do this, I rely on what I call “simplicity.” But there is nothing simple about this concept. Indeed, it is a puzzle of complexity.

The 19th-century poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow said, “In character, in manner, in style, in all things, the supreme excellence is simplicity.” I side with Longfellow.

To achieve simplicity, it is necessary to pare away excess and select just what is essential and meaningful. Design icon Albert Hadley said, “The designer must develop an overall concept and stick to it.” Early in my career, I was on a quest for this “concept” that Hadley spoke of. At the time, I was struggling with the design of my own living room. A friend asked, “Can’t you just make it pretty?” I thought, Well, yes. But I want it to be something more. Pretty was not enough.

By chance, a friend gave me a book on the legendary Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel. If there was ever a designer with a unique style, it was Chanel. She fascinated me. I began to learn about her—and her famous “little black dress.” When Vogue printed an illustration of her first little black dress in 1926, the editors called it Chanel’s “Ford.” Like the Model T, it won high praise. Both were new, simple, sleek, and black. Both changed the world.

Today the little black dress is a wardrobe must, a long-standing concept in fashion. Chanel was famous for saying, “Scheherazade is easy; a little black dress is difficult.” What did she mean? Simply that ornament, decoration—“the fancy stuff”—is entertainment. It’s fun. It’s pretty (there’s that word again). It’s diverting. But that little black dress—it’s serious. It’s complex. It’s a challenge. It’s simplicity. In 1923 Chanel told Harper’s Bazaar, “Simplicity is the keynote of all true elegance.”

I have now learned, with a great deal of work and experience, that this simplicity has structure, rules, and guidelines. I have developed my rules, my guidelines, which I call elements of design. Every project, regardless of its style, involves these elements. And there is a definite hierarchy. In order of importance, they are: architecture, composition, proportion and scale, color, pattern, texture, and craftsmanship.

I am often asked to explain the “how” and “why” of these principles. Each time, I find myself thinking about Chanel and her little black dress. For me, the LBD is a simple, powerful, dynamic gesture of one’s individuality. It is something to rely on, something comfortable, something to fill you with ease and confidence. It is for the body what the home should be for the family.

Interestingly, my elements of design parallel the success or failure of the little black dress. The fashion designer’s challenge is to translate these elements into the perfect human fit. The interior designer’s challenge is to translate these same elements into the design of a home—and, like Chanel, to do it simply, straightforwardly, and without gimmicks. Let me show you how I apply these elements to both fashion and interiors.

Architecture

For me, this is the most important element of design. It is the beginning, the sculptural skeleton of every project. Everything depends on the architecture.

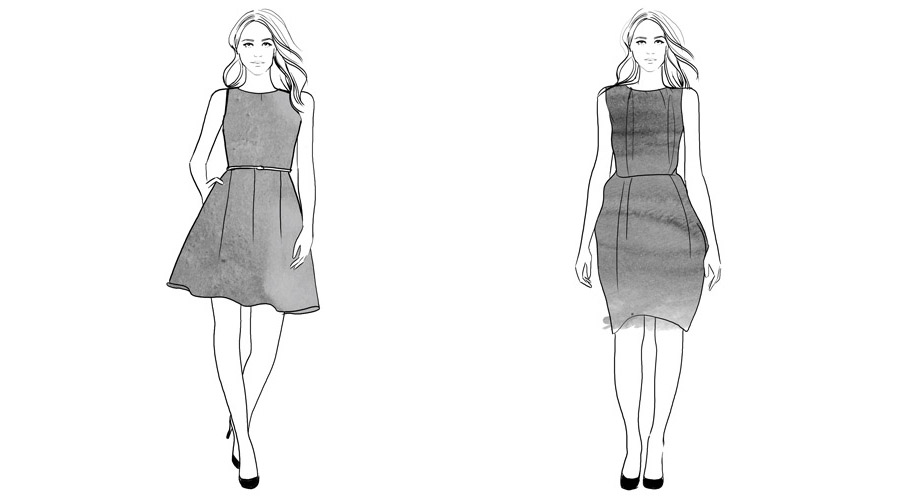

In fashion, a well-constructed dress (left) has simple, strong dimensions. It might have subtle details like a fitted torso or a flared skirt. But it has straightforward, strong structure—in other words, architecture. The other dress (right) is shapeless and ill-fitted. No amount of accessorizing will redeem it.

The design master Billy Baldwin said, “I’ve always believed that architecture is more important than decoration. Scale and proportion give everlasting satisfaction that cannot be achieved by only icing the cake.”

The country room above has the kind of good bones that Baldwin spoke of: high ceilings, antique beams and boards, well-proportioned windows, and an intriguing arched passageway.

When architecture is true and powerful, the designer’s job becomes so much easier.

Composition

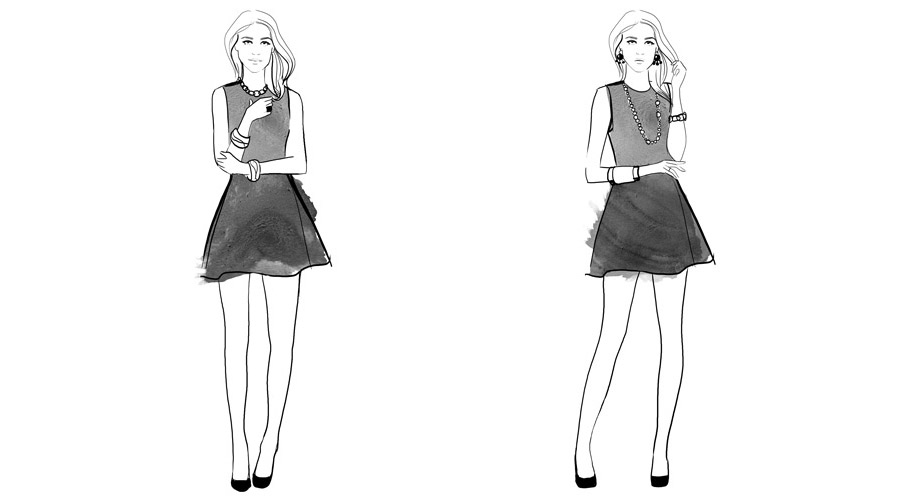

This is the arrangement of objects within a given space. Let’s see how it applies to the little black dress. On the right, the jewelry pieces—cuff, link bracelet and necklace, earrings—do not relate to one another. On the left, each piece reinforces and responds to the others, in material and style. The composition is happily balanced.

Every room contains numerous compositions. They begin with larger seating arrangements and extend down to smaller arrangements on a mantle or tabletop. Each part of an individual composition must complement each other and enhance the group as a whole.

The country interior derives its success from the aggressive use of symmetry and repetition, a compositional solution I use often. Two matching chandeliers; four wing chairs and a pair of identical sofas, covered in the same textured linen; all accented by a pair of boxwood topiaries. A simple and balanced composition.

Proportion & Scale

Proportion is the relationship of one part of an object to another. Scale is the size of an object, its parts, and its relationship to other objects and their parts. Look at how we’ve accessorized the little black dress. On the right, a large shawl, oversized handbag, and flat shoes visually alter the proportion and scale of the dress. We have successfully driven this LBD into the ground. On the left, the handbag and shoes are properly proportioned and scaled. There are no black hose to shorten the torso.

Eleanor McMillen Brown, a pioneer in interior design, said, “The basic rules of proportion and scale are unchanging. The most important element in decorating is the relationship between objects, in size, form, texture, color, and meaning.”

For example, in the contemporary study above, a boldy designed armoire persuasively states its presence with large proportion and scale.

Color

Nothing in design is more compelling or personal than color. On the right, blue accessories engulf the LBD, but, a touch of red adds a happy bit of playfulness and focus on the left. The lesson here is easy to see. Color should always be helpful, not hurtful. One should always choose color to support the design intent. For pure potency, color beats everything else in the room. And don’t forget, as Coco Chanel said, “Black has it all; white too. It is the perfect harmony. Their power is absolute.” That is the color palette I chose for the contemporary room above, which appears on the cover of my book.

The number of patterns available to the designer is endless. Pattern is an element that must be carefully chosen, mixed with purpose, and artfully applied. Here are two different takes on one of my favorite patterns, spots, on the LBD. On the right, a spotted mess, I think. The patterns do not mix well, and they obscure the dress. The left’s dotted shoes combined with the dots on cuff bracelets show pattern that is restrained and artfully used.

Billy Baldwin said, “Great blends of pattern, like great dishes, must be carefully tasted. And constant tasting is what teaches a cook how to taste.” I’ve tasted a lot, and I’ve found that to be true.

If a room lacks a visual focus or is in need of visual jazz, pattern can provide it. But pattern should never overwhelm or disguise the object onto which it is placed.

Above, a flock of sheep happily graze amid the dots that playfully animate this contemporary children’s bedroom.

Texture

Every object has a texture that adds dimensionality: rough or smooth, diaphanous or hefty, matte or shiny. It is important to consider the purpose and function of the object onto which the texture is being placed to create a functional and happy marriage.

Look at the LBD on the right: It is weighted down by too much shine, too much straw—not a happy mix. On the left, we have matte and shiny again, but this time in a simple, elegant, restrained textural composition.

All objects, materials, and works of art tell us a great deal about what they are through their surfaces.

For example, natural textures, airy and lightweight, give the beach bedroom above a palpable softness. The chairs are abaca, the draperies are an open-weave linen, and the rug is woven of multiple grasses.

Craftsmanship

Without highly skilled craftspeople, designers cannot turn their vision into reality. The more skilled the craftsman, the more successful the outcome.

The quality of workmanship is evident in clothing. The dress on the right is a poorly crafted garment that looks more like a sack than a dress. The unstructured bodice and uneven hemline tell the story. On the right, a designer dress has impeccable seaming and fit; it has couture-level craftsmanship.

This principle also plays a role in interior design. Craftsmanship can transform an ordinary space into an extraordinary one.

One craftsperson I admire is Robert Kuo, a Chinese artist whose work is in the Smithsonian. Inspired by organic forms, he reinterprets nature. Above, his copper toads travel to and fro across the stone—perhaps in search of a drop of water to drink?

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)