This article originally appeared in our July 2011 issue.

As midnight approached on Friday, July 26, 1996, there were still 15,000 people crowding Centennial Olympic Park. A heat wave that had kept temperatures hovering near 90 degrees for the past week had broken, and there was a cool breeze in the air.

For eight days, ever since Muhammad Ali lit the Olympic cauldron to open the Summer Games, the eyes of the world had been fixed on Atlanta. A stroll through Centennial Park meant overhearing conversations in exotic tongues, or standing in line behind someone from Ireland while standing in front of someone from Nigeria, or swapping pins with a visitor from Australia.

If you were there that evening, you may have passed by twenty-nine-year-old Eric Robert Rudolph, dressed in jeans and a blue short-sleeve shirt. A large pack was strapped to his back. Rudolph had grown up in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he had come under the influence of Nord Davis Jr. Besides being a former IBM executive, Davis was the leader of the Christian Identity movement, which posits that Jews are the children of Satan and that Christ cannot return to Earth until the world is swept clean of the devil’s influences. Davis said often that the movement needed a “lone wolf”—an agent who could plan and execute an attack all on his own, telling no one.

For the past seven years, Rudolph had been a voracious reader of the Bible and of hate-filled propaganda denouncing gays, abortion, the government. He worked odd jobs, always demanding cash payment, and grew marijuana. He filed no tax returns and had no Social Security number. Two months before the Games, he told his family he was moving to Colorado, but actually he stayed in North Carolina. At some point, he decided to plant bombs on five consecutive days at Olympic venues, each one preceded by a warning call to 911. His goal was simple: shut down the 1996 Summer Olympic Games.

As the R&B band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack took the AT&T Stage that evening, Richard Jewell, a thirty-three-year-old security guard, kept watch near the sound and light tower. Born in Virginia, he moved to DeKalb County with his mother when he was six, after his parents divorced. He graduated from Towers High School and worked as a clerk at the Small Business Administration. A lawyer he befriended there would describe Jewell as earnest, sometimes to the point of being annoying.

Jewell always wanted to be a cop. In 1990 he landed an entry-level job as a jailer with the Habersham County Sheriff’s Department. While working a second job as a security guard at his DeKalb County apartment complex, Jewell was arrested for impersonating an officer; he pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct and was put on probation.

He worked as a deputy sheriff for five years, and he was remembered for his zeal for the job and his tendency to wreck patrol cars. After his fourth crash, Jewell was demoted back to jailer. He chose instead to resign.

He was hired as a campus cop in 1995 at the tiny Piedmont College in Demorest. It was an ill fit. Jewell would write long, detailed reports on minor incidents. He upset college officials when he stopped someone for operating with one taillight. Although the main highway ran past the school, traffic violations were supposed to be handled by the Demorest police. He got into trouble when he made a DUI arrest on the highway and didn’t follow protocol by radioing the police department to handle the case.

He resigned in May of 1996 and moved into his mother’s apartment on Buford Highway. She was about to have foot surgery; he wanted to be there for her and also to find a police job in the Atlanta area after the Games. In June he began working for a security firm contracted by AT&T, which was building a stage in Centennial Park. Jewell joked to a friend that if anything happened at the Games, he wanted to be in the middle of it.

Saturday, July 27

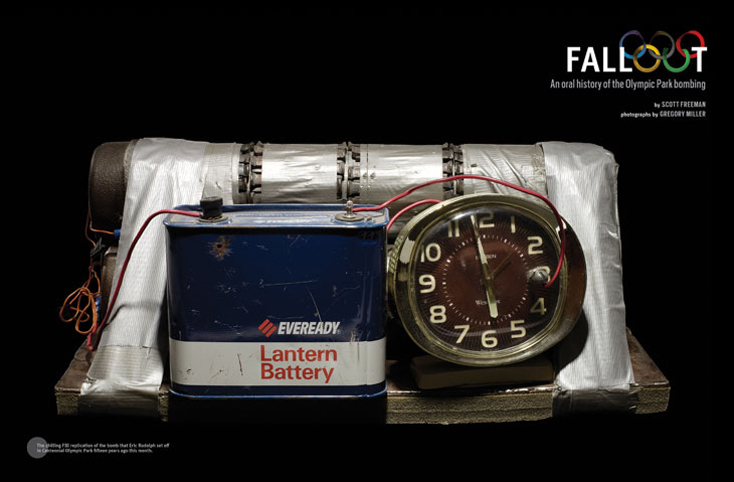

Rudolph found an out-of-the-way spot in front of the sound and light tower that faced the AT&T stage. Inside his backpack were three pipe bombs filled with gunpowder and six pounds of 2.5-inch steel nails, stuffed into Tupperware containers. The bombs were powered by an Eveready six-volt lantern battery hooked to a model rocket engine igniter and triggered by a Westclox alarm clock.

Rudolph put the bag on the ground, reached inside, and set the alarm to go off in fifty-five minutes. There were three benches in front of the tower. The one to his left was tucked against a steel barrier that paralleled what is now Centennial Olympic Park Drive, and he stashed the bag under that bench. Michael Cox, who worked for the Turner Associates architectural firm, and some friends were at the bench minutes before Rudolph’s arrival.

Michael Cox: We were sitting on that bench about thirty minutes before the bomb went off, and we saw Eric Rudolph in the park. He really stood out; well, it was his backpack that stood out, because it was huge. It wasn’t a hiker’s backpack; it was big and boxy. I remember wondering, why in the world would somebody be wearing a backpack like that?

Sometime after midnight, the band took a break. During the lull, a group of seven college-aged men walked up to the three benches in front of the sound tower. Five of them sat on the middle bench; the other two sat on the bench above the bomb.

They were drunk and rowdy, which drew Jewell’s attention. He noticed they had two large bags. The one in front of the middle bench looked like a canvas cooler, and he saw them pull fresh Budweisers from it. The other was a large, green, Army-style backpack that was shoved under the bench by the steel wall.

Jewell called over Tom Davis, a GBI agent who was working security in the park.

Tom Davis: [He] flagged me down and told me he’d been having a problem with drunks throwing beer cans into the tower. He said, “They won’t listen to me; I need someone in law enforcement to talk to them.”

We walked around the tower and saw a couple of guys picking up beer cans. Richard Jewell said, “That’s a couple of them, but the rest have left.” Then those two left. We’re standing by the tower, and he looks down at this bench and says, “One of them must’ve left that bag.”

Richard Jewell: It was just that casual. Tom turned around and hollered at them, “Did you all leave a bag up here?” And they said, “No, it ain’t ours.”

There were at least a couple hundred people sitting on a grassy knoll in front of the tower. Davis and Jewell quickly asked those closest to the benches if the bag belonged to them. When no one claimed it, Davis followed procedure; he declared it a suspicious package and called for the bomb team. Jewell radioed his supervisor.

They then cleared a fifteen-foot perimeter so the bomb team would have room to check out the backpack. It was 12:57 a.m. One minute later, Rudolph called 911 from a pay phone five blocks away from the tower. He announced in a calm, flat voice, “There is a bomb in Centennial Park. You have thirty minutes.” He was wrong; they had only twenty-two. While Davis waited for the bomb team, Jewell went inside the five-story sound tower.

Jewell: I went to each floor very quickly and [said], “We’ve got a situation in front of the tower. Law enforcement is on the scene, and they [are] checking it. I don’t know what it is right now, but it is a suspicious package. If I come back in here and tell you to get out, there will be no questions, there will be no hesitation. Drop what you’re doing and get the fuck out.”

After I got to the top, I came back down, and the whole time I was counting people. I wanted to make sure I knew how many people I had in the tower. [There were] eleven people.

By the time Jewell emerged, the bomb team had arrived. So had Jewell’s supervisor, Bob Ahring, an assistant police chief from Blue Springs, Missouri.

Jewell: The guys looked at it from every angle, and then finally one of them took out a penlight and laid down on the ground and crawled under the bench, and then he loosened the bag and shined the light inside. All of a sudden . . . he just froze, and then he crawled out just as slow as molasses in wintertime.

Bob Ahring: I asked one of the guys, “What have we got?” I could see he was shaken. “It’s big,” he said. “How big?” I asked. “Real big,” he said. I said, “Do we need to evacuate?” The guy just vigorously nodded his head.

Davis and Ahring were quickly joined by other officers to help get the crowd away from the tower, and to do it without inducing panic. Jewell hurried back into the tower, which stood to take the brunt of the impact if the bomb exploded.

Jewell: I said, “Get out! Get out now!” Went to the second floor: “Get out! Get out now!” Third floor, nobody was there. Up to the fourth floor. Told the video guy, “Let’s go! Let’s get out of here!” Went up to the [light box], said, “Let’s get out of here! Let’s go now!” They were wanting to cut their spotlights out. I grabbed both of them and pushed them down the stairs.

I came down to the video floor. The guy’s putting videocassettes in his briefcase. I reached over there and grabbed him by the arm and just drug him down the stairs with me. Came down to the third floor. It was clear. Went down to the second floor. Everybody had cleared out of there. Went down to the first floor. Checked it again. I was the last one out of the building.

One of the troopers walked up, “Is the tower clear? Is the tower clear?” I said, “Yeah, it’s clear, 100 percent clear.”

If we’d had three more minutes, we’d have [cleared the area]. All these benches were still full of people. They wouldn’t move. Every one of them had four and five people on them. The [officers] lined theirselves up with the benches. When that thing went off, they took all the shrapnel that those people would have took.

Davis: I know exactly where I was standing when it went off; I was eighteen steps from where it detonated. It was very loud, and it was very forceful. The vacuum it created was immense and shoved me forward. I remember the heat from it on my back.

Ahring: I was just ten yards away. The concussion knocked me forward six feet, and I wound up on the ground. There was smoke everywhere, the smell of gunpowder. There was a sudden deathly quiet throughout the whole park, and I could hear the whistle of shrapnel whizzing through the air. It was the eeriest thing I’ve ever heard in my life.

Jewell: I’d been out of the tower maybe a minute and “kabang!” It knocked me forward, and I fell down on my hands and knees. As I pushed myself back up, I looked to my right because that’s where the blast come from. Those troopers that had been lined up with those benches were flying through the air. It had knocked them that far. I started running to those—hell, they’re my buddies. I get to the first guy and I’m helping him lay down. I’m telling him, “Just lay flat, man. We’ll get you some help, man.”

Every one of these guys is a bigger fucking hero than I am. If I’m a hero, there ain’t a word to describe these guys right here. I mean, it wells me up every time I think about it.

Alice Hawthorne, forty-four, who had driven from Albany, was killed by shrapnel. Hawthorne was hit six times, including a fatal wound to the head. Melih Uzunyol, a Turkish news cameraman, died of a heart attack while rushing to the scene. In total, 111 others were injured. Ahring was hit in his left shoulder and lower left leg. Davis was hit as well, in the buttocks. But the GBI badge holder in his back pocket blocked the shrapnel.

Among the injured was John Fristoe, a stagehand who heard about the bomb threat from security and was walking toward the tower to warn a friend inside. The force of the blast caused a whiplash that collapsed a disc in his neck, an injury that almost paralyzed him.

John Fristoe: Ms. Hawthorne, I saw her. She was coming down the hill [head over heels]. Seriously. It was horrible, man. [begins to weep] I’m sorry. I’ve never witnessed a murder before.

Davis: It was utter chaos. We had troopers down and agents down. There was screaming and hollering. I remember checking on Ms. Hawthorne. She had already expired. A man beside her was bleeding profusely from the stomach area where shrapnel hit him.

The Centennial Park bombing put the city into a state of shock. The immediate question was whether the Games would continue—was it even safe for the Games to continue? Ed Hula covered the Atlanta Games for WGST-AM. Today he is editor of Around the Rings, a web-based publication considered an authoritative media source of Olympic news.

Ed Hula: There were questions: Is this an isolated instance? Will there be more of these? How can we go on with the Olympics with a couple of people dead? Some said the Games shouldn’t continue, but they did. There was precedent—the Munich Games in 1972. That was more dastardly, more consequential, and much more of a significant event than the Centennial Park bombing. And those Games continued.

Nancy Geery: During the Olympics, I worked at a recruiting firm. Everyone was caught up in the spirit of the Games, and I wanted to be involved, so I worked nights in a Swatch kiosk selling watches. I was in the park the night of the bombing. It was very festive, a lot of camaraderie. Afterwards there was fear in the back of your mind. I was twenty-six at the time. I had tickets to the track and field finals, really fantastic seats, and I went. At that age, I was not as afraid of things. Now? Oh no, I would’ve never gone back there.

Cox: The city had been on a euphoric high because of the Olympics for weeks and weeks. The bombing was a sucker punch to the gut. I was outraged that someone would do that to the Olympics in my hometown.

Late Saturday morning, officials held a press conference and credited a security guard with discovering the bomb before it exploded, which had enabled officials to move a large number of people out of harm’s way.

CNN was the first news organization to get an interview with the guard who found the bomb. Bryant Steele, who handled media relations in the Southeast for AT&T, met Jewell outside the CNN Center around 7:30 that evening and escorted him inside. Jewell wore one of the security firm’s black polo shirts and a black cap. He had barely slept in the past twenty-four hours.

Jewell: [My mother and I] got there late because we couldn’t park anywhere near Downtown. They literally ran us straight to the control room, sat me down, put a mic on me, and said, “Be ready in about five seconds.” I told them I’d never done anything like that before, and I was very nervous about it. They told me to be myself and just go tell what happened.

Bryant Steele: I said to [Jewell] that there would be more of these interview requests coming up and you need to think about your willingness to do them.

Jewell: I told them that I would do whatever they wanted me to do. They would call me up and say, “Do you mind doing this?” And I would say, “No, that’s fine if that’s what you all want me to do.” I worked for them. I felt obligated that I needed to do what they asked me to do.

Sunday, July 28

CNN aired the Jewell interview over and over in its coverage of the Centennial Park bombing. He was heralded as a hero of the Summer Games.

That morning Steele drove Jewell to a ninety-minute session with the FBI to go over everything he’d seen the night before. Steele then took Jewell back to CNN to tape a more in-depth interview. While they were there, USA Today paged Steele. Then the Boston Globe. They wanted interviews with Jewell.

Because they were in Downtown, Steele decided to call the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He said he considered it a courtesy to the hometown paper.

Steele: I told them that both CNN and USA Today were interviewing the security guard who found the knapsack that contained the bomb in Centennial Park. I told them I was accompanying him to his interviews, and if they would like to also interview him, I would be glad to bring him over.

One person who watched the CNN interview was Ray Cleere, the president of Piedmont College. According to a Justice Department audit of the FBI’s CENTBOM investigation, Cleere called the FBI Sunday afternoon and expressed concern that Jewell may have been involved in the bombing. Cleere also said the college had information concerning “improper conduct,” as he phrased it, by Jewell—a reference that turned out to be nothing more than Jewell’s practice of stopping cars on the highway that went past the campus.

Cleere and Dick Martin, the chief of the campus police, contended in their depositions that the intent was simply to tell the FBI the college would cooperate if the FBI did a due diligence background check on Jewell.

Ray Cleere: We agreed that the investigation would begin with anyone that might have been in the area [of the bombing], including the officers involved. We felt that we would soon be contacted by law enforcement. We agreed that we should cast the institution in the proper light by agreeing to cooperate in any way [that] we were called upon.

Dick Martin: We had no belief that Richard Jewell was involved in this bomb. We said that clearly. I said that the first time I called, that we were only volunteering what information we had about his employment. That was it.

I think I did use the word “with a slightly erratic work record” or something to that effect. [And one of my officers] told me, “Richard did have a little knowledge of bombs. Me and Richard talked about bombs several times.” That caught me by surprise. My feelings were, “Gosh, I wish I hadn’t heard that.” I had a feeling that this was going to kind of muddy things up.

The pressure on the FBI in the wake of the bombing was intense. This was the Olympic Games. The entire world was watching and wanted to be reassured that the FBI would catch the bomber before he struck again.

There was little to go on. No radical group claimed the bombing. There was only preliminary forensics; there were no eyewitnesses who saw the bomb being planted and no information from inside extremist groups.

Eric Rudolph had played the lone wolf to perfection. He had abandoned his plan to set off four more bombs and was already back in North Carolina.

FBI Director Louis Freeh participated in a twice-daily conference call between Washington and the Atlanta FBI field office. According to the Justice Department audit, Richard Jewell’s name arose for the first time Sunday, July 28, during the 5 p.m. call.

Aside from Cleere’s phone call, there were two factors that elevated Jewell’s name as a potential suspect. A recent spate of fires in Southern California turned out to have been set by a volunteer firefighter so he could extinguish them and become a hero. And at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, a security guard had planted a fake bomb on a bus in order to discover it later.

FBI headquarters agreed to begin a “preliminary investigation” into Jewell’s background.

Monday, July 29

FBI agents arrived at Piedmont College and Habersham County early in the morning. They found out Jewell had owned a green backpack similar to the one used in the bombing, that Jewell had access to a bomb-making “cookbook,” that he had told someone he wanted to be “in the middle” of anything that might happen at the Olympic Games.

They learned Jewell had been on a task force that handled bombs, and that Jewell had told a fellow officer he’d dealt with homemade pipe bombs that had a closed chamber, contained shrapnel, and were set off with blasting caps. One person who knew Jewell told the FBI he thought Jewell was capable of placing a bomb if he thought no one would be hurt by it. He said Jewell might have believed that this could make him appear heroic and help him get a job as a police officer again. He said Jewell had been “blackballed” from law enforcement because of his history as a deputy sheriff. The agents also learned he had once been arrested for impersonating a police officer.

Jewell was discussed during the FBI’s 9 a.m. conference call between Washington and Atlanta. They learned that behavioral specialists in Quantico, Virginia, had watched Jewell’s CNN interviews and decided he “fit the profile of a person who might create an incident so he could emerge as a hero.” That afternoon the possibility of interviewing Jewell was discussed but was tabled for twenty-four hours.

In the evening, the AJC’s Kathy Scruggs—who then covered the Atlanta Police Department—caught wind of the FBI’s interest in Jewell from a source.

Kathy Scruggs: He said, “But you can’t do anything with this until I say so, because it might screw up the investigation, might ruin the investigation.” So I said, “Okay, unless I get independent corroboration. And then, that changes the rules. I am in a different ball game.” And he said, “Okay.”

Ron Martz, then AJC reporter: After Kathy told us that her sources were telling us that Mr. Jewell was the prime suspect, there was a discussion about whether we had sufficient information or sufficient time to get that story into the newspaper the next morning. And we quickly came to the realization that we did not.

We decided to dispatch [reporter] Maria Fernandez to Habersham County. Meanwhile I would be working my sources to try to get confirmation of what Kathy’s sources were telling her.

Scruggs: From the beginning, we knew that he fit the alleged profile and that his former employer called to turn him in. I also knew that they had information, which I don’t know at this point that they verified or not, that he had been involved with someone else in making a bomb before . . . Apparently Jewell’s handler had approached the paper about doing a story about him being a hero.

Someone at AT&T had given Jewell tickets to an Olympic baseball game, and he spent Monday afternoon with his mother at Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium. Around 8 p.m. he received a call from Tim Attaway, a GBI agent he knew from North Georgia who also was working security in the park. Attaway sounded homesick, and Jewell invited him over for some home-cooked lasagna.

Attaway had an ulterior motive. At the request of the FBI, he wore a Nagra tape recorder strapped to his back. Jewell talked about the bombing until 1 a.m., even though he had to be awake at 5:30 Tuesday morning. Centennial Park was to reopen, and he was to be interviewed by Katie Couric on the Today show.

Jewell made the appearance Tuesday, then went home. He wanted to catch a few hours of sleep before he went back to work that evening.

Tuesday, July 30

The FBI held its conference call at 9 a.m., and Freeh told the Atlanta office to conduct a non-confrontational interview with Jewell late that afternoon, then follow it up on Wednesday with a confrontational interview and possibly a polygraph.

They faced two significant problems in building a case against the security guard. First, agents had yet to turn up any direct evidence that implicated him. Second, the FBI had just learned that the 911 call was placed at almost the exact same time Tom Davis radioed for the bomb squad; that meant Jewell was standing next to Davis in Centennial Park when the 911 call was made from a phone booth five blocks away.

Around midmorning an even bigger issue came into play.

Martin: On Tuesday, when [FBI agent] Don Johnson left my office, he said, “If we could just have one more day, one more half day even, without the press, this young man will be able to go on with his life without anybody even knowing about [this].”

Scruggs: I was coming in to work, and I got a beep from the Atlanta police. When I called them, they said they are looking at the security guard. I said, “How did you know that?” He said, “Well, we are over here talking about it. Everybody knows it.”

My feelings were that once this had gotten to the Atlanta Police Department, that it would be pretty much common knowledge. I came into the office and told them, “I think we need to go with the story.”

The AJC story—cowritten by Scruggs and Martz—was printed in the paper’s daily “extra” edition that hit the streets around 3:30 Tuesday afternoon. Within minutes a CNN anchor raised the front page headline to the camera: “FBI Suspects ‘Hero’ Guard May Have Planted Bomb.” He then read the story aloud word for word:

“The security guard who first alerted police to the pipe bomb that exploded in Centennial Olympic Park is the focus of the federal investigation into the incident that resulted in two deaths and injured more than 100.

“Richard Jewell, 33, a former law enforcement officer, fits the profile of the lone bomber. This profile generally includes a frustrated white man who is a former police officer, member of the military or police ‘wannabe’ who seeks to become a hero.

“Jewell has become a celebrity in the wake of the bombing, making an appearance this morning at the reopened park with Katie Couric on the Today show. He also has approached newspapers, including the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, seeking publicity for his actions.”

Lin Wood, civil attorney for Jewell: Bobi Jewell and Richard were watching the Olympic broadcast that night. And here’s Tom Brokaw telling the world—Tom Brokaw—that they probably have enough to arrest him, probably enough to prosecute him, but they want to fill in a few more holes in the case. But the only name you’re hearing tonight is Richard Jewell.

And Bobi Jewell, whose favorite news anchor was Tom Brokaw, turned to Richard and said, “Son, what have you done?”

The Aftermath

In the days that followed, television news crews and reporters swarmed the parking lot in front of Bobi Jewell’s Buford Highway apartment. The day after the AJC story hit, the FBI searched the apartment while Richard Jewell sat outside in view of the media.

The AJC’s follow-up stories said that Jewell fit the profile of an overzealous “police wannabe” who planted the bomb in order to be a hero and then sought the limelight. That he had a reputation “as a badge-wearing zealot.” That he was a “bad man to cross on his beat.” The paper had one handicap: Scruggs’s original source stopped speaking to her.

In a column that ran on August 1, AJC columnist Dave Kindred evoked convicted killer Wayne Williams, suspected of murdering more than twenty children in Atlanta between 1979 and 1981. “Once upon a terrible time, federal agents came to this town to deal with another suspect who lived with his mother,” Kindred wrote. “Like this one, that suspect was drawn to the blue lights and sirens of police work. Like this one, he became famous in the aftermath of murder. His name was Wayne Williams. This one is Richard Jewell.”

Wood: You read all that in the newspaper, what are you going to think except that Jewell’s some weirdo who bombed the park? You say, “That son of a bitch, he did it.”

Except it’s not true. He never contacted the AJC. He never contacted any newspaper. He never contacted any media organization. There’s no profile of the lone bomber in the FBI parlance. Those statements were totally without attribution, in the voice of God, saying that Richard Jewell fit this profile. No one ever said that about Richard.

The problem is that Richard was the sexy one. He was the hero they could now argue was the killer. That had such sex appeal with the media, they couldn’t resist it.

Peter Canfield, lawyer for the AJC: At the time of the Journal-Constitution’s story, reports on the hero guard were in the local and world news daily, and Richard Jewell was continuing to make appearances on national talk shows. That he was the FBI’s prime bombing suspect was not just news—it was stunning news.

When the Journal-Constitution’s reporters were tipped to this fact, they confirmed that Richard Jewell was the prime suspect—and why he was the prime suspect—and accurately reported that to readers. Should the Journal-Constitution have questioned the FBI’s theories as to Richard Jewell’s guilt? Yes, and it did, with more determination and effect than any other news organization.

Bert Roughton (then Olympic news editor): I don’t accept the assertion that the newspaper was less than accurate, nor do I think we were moved improperly by competitive desires. I know that Mr. Jewell, or somebody representing Mr. Jewell, had contacted our newspaper offering him to be interviewed, in fact, promoting the story. There was a general impression at the time that he was making the media rounds, talking to a number of other news organizations.

John Walter (then managing editor): [Our] story is blatantly true. Everything we said became even more visible in the next twenty-four to forty-eight hours.

The majority of the press—including the New York Times and the Washington Post—took a much more conservative approach to the bomb investigation.

Jewell was a focus of the FBI’s efforts, but he was far from the only focus. On July 31, the Associated Press and CBS News reported the investigation was moving away from Jewell. That same day, ABC News reported that the FBI had failed to turn up physical evidence linking Jewell to the bombing, and that there were questions about whether Jewell could have placed the 911 call.

As late as August 4, the AJC stated that “investigators have said they believe Jewell, a security guard in the park who was originally credited with finding the bomb, planted the bomb and phoned in a warning to 911.”

Scruggs: That’s what I was told at the time. You have to rely on what police tell you. We don’t have the tools that they have, the pieces to the puzzle.

Wood: The AJC was the only news organization in the world to report that investigators believed Jewell planted the bomb, and that investigators believed Jewell placed the 911 call himself. No one else reported that. No one else even republished that statement.

The media’s obsession with Richard Jewell was a blessing and a curse for the FBI. As the Games continued, it meant the public was reassured that the FBI had their guy and everyone could feel safe again. It also boxed the FBI into a corner. They had no choice but to continue to let Jewell twist in the wind. If they cleared him now and something turned up later to implicate him, they’d look like fools.

For nearly three months, everywhere Jewell went—to the grocery store, to a Braves game, to his lawyer’s office—he was trailed by a convoy of FBI vehicles.

When Mike Wallace met with Jewell in September with a 60 Minutes crew, he asked for proof of the spectacle. One of Jewell’s lawyers, Watson Bryant, told him the agents were downstairs in the parking lot.

Watson Bryant, Jewell’s lawyer and long-time friend: So Mike Wallace gets a cameraman, and we all go downstairs, out the front door. And now I know how to get rid of FBI agents: You just come at them with a news camera, and they’re like roaches, they just disappear.

Wood: Everybody wanted that interview, and we decided to go with Mike Wallace because he had the reputation of being the toughest newsman in the business. We felt that if we had Richard answering any question that Mike Wallace might throw at him, then the public would understand that Richard Jewell was an innocent man.

The 60 Minutes story was broadcast on September 22 and portrayed Jewell as the hapless innocent, his life turned upside down by the media and the FBI. It showed several shots of Jewell being followed by the parade of dark-colored SUVs and sedans, and Wallace ridiculed the heavy-handed approach. That story, coupled with a press conference Bobi Jewell gave in August, convinced Attorney General Janet Reno to tell the FBI to review the Jewell investigation.

On October 6, the FBI interviewed Jewell for nearly six hours. At the conclusion, assistant U.S. Attorney John Davis told Jewell the government didn’t think he planted the bomb. Twenty days later, U.S. Attorney Kent Alexander hand-delivered a letter to Jewell’s defense lawyer that made it official. After eighty-eight days, the hounding of Richard Jewell was over.

Postscript

Richard Jewell sued and/or reached settlements with Tom Brokaw and NBC News, CNN, the New York Post, Time magazine, and Piedmont College.

He filed a lawsuit against the AJC in 1997, which was dismissed by a Fulton County judge in 2007. Jewell appealed that decision to the Georgia Court of Appeals; oral arguments were heard in February. The AJC stands steadfast in its assertion that the coverage of Richard Jewell was “fair, accurate, and responsible.” Kathy Scruggs said in a 1997 deposition that her sources still believed Jewell was involved in the bombing.

After the Games, Scruggs was promoted to cover federal law enforcement. She died in 2001; John Walter died in 2008. Bert Roughton is now managing editor at the AJC. Ron Martz took a buyout when the paper was downsized

in 2007.

Six months after the Olympics, a pipe bomb was set off in Sandy Springs outside an abortion clinic. A month later, on February 21, 1997, another bomb exploded behind the Otherside Lounge, a lesbian bar in Atlanta. Only then were federal investigators able to forensically link the three bombings in the Atlanta area. In 1998 Eric Robert Rudolph was seen fleeing the scene of a bombing outside an abortion clinic in Birmingham that killed an off-duty police officer. Once he was identified, Rudolph disappeared into the mountains of North Carolina and eluded capture for nearly five years.

On April 13, 2005, Rudolph pleaded guilty to the bombing in Centennial Park and three other bombings. He was sentenced to four consecutive life sentences without the chance of parole.

In 2006, on the tenth anniversary of the Games, then Governor Sonny Perdue honored Richard Jewell for his heroism on the night of the bombing. Just over a year later, Jewell died in his Meriwether County home at the age of forty-four of complications from diabetes. He was working as a deputy sheriff. Bobi Jewell still lives in the Atlanta area; through her lawyer, she declined to be interviewed.

Fristoe, the stagehand who had been injured in the blast: On the day Eric Rudolph was sentenced, I was there in the courtroom. They called me up to the stand to address him. I told him, “I can’t understand why you did what you did. But I’ve prayed for you.” He didn’t react, but I know he heard me. I got some closure because of that.

Richard Jewell, God rest his soul. When we were building that sound tower, it was close to a hundred degrees. He was working security, and he brought me iced water time and time again. He was really a courteous guy. He’s so misunderstood.

Geery: All I remember is Richard Jewell. I don’t even remember the guy who did it

Bryant: He was always just a decent guy. In the fall of ’96, I had him coach [Northside Youth Organization] football, and there was a lot of trepidation from the parents. He’s out there with the team, and one of the kids asks about the men standing over to the side of the field. Richard said, “Well, those are FBI agents, and they’re here to keep an eye on me, make sure everything’s okay.” These were nine- and ten-year-old boys, and they were excited: “Really? FBI? Really?” He says, “Come on, let me introduce you to them.” He took the team over, and these agents, they showed them their badges and their guns and they answered these kids’ questions. The parents, they figured it out quickly enough.

He was a good man. I miss him.

About This Story

For this oral history, Scott Freeman relied on both archival and fresh interviews. He also reviewed nearly 20,000 pages of legal documents compiled from Richard Jewell’s lawsuit against the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Most of the AJC editors and reporters involved have never spoken publicly about the paper’s coverage, so Freeman drew from portions of their sworn depositions. The court file also contains interviews concerning the bombing coverage that an AJC reporter conducted for a story that was never published. Quotes from Richard Jewell come from FBI files and depositions. Freeman drew additional information from the FBI case file and interviews, as well as from a Justice Department audit of the Jewell investigation. Eric Rudolph discussed the Olympic Park bombing in a manifesto posted on the Army of God website. Some quotes have been edited for clarity. Disclosure: AJC lawyer Peter Canfield represents Freeman in a lawsuit filed over one of his books, and Bryant Steele was Freeman’s city editor at the Macon Telegraph in 1983.

SOURCES FOR QUOTES

Richard Jewell – Depositions, FBI files

Michael Cox – Interview with author

Tom Davis – Interview with author

Bob Ahring – Interview with author

John Fristoe – Interview with author

Ed Hula – Interview with author

Nancy Geery – Interview with author

Bryant Steele – Deposition, interview with author

Ray Cleere – Deposition

Dick Martin – Deposition

Kathy Scruggs – Deposition

Ron Martz – Deposition

Lin Wood – Interview with author

Peter Canfield – Interview with author

Bert Roughton – Deposition

John Walter – Deposition

Watson Bryant – Interview with author

This article originally appeared in our July 2011 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)