Photograph by Rachel Garbus

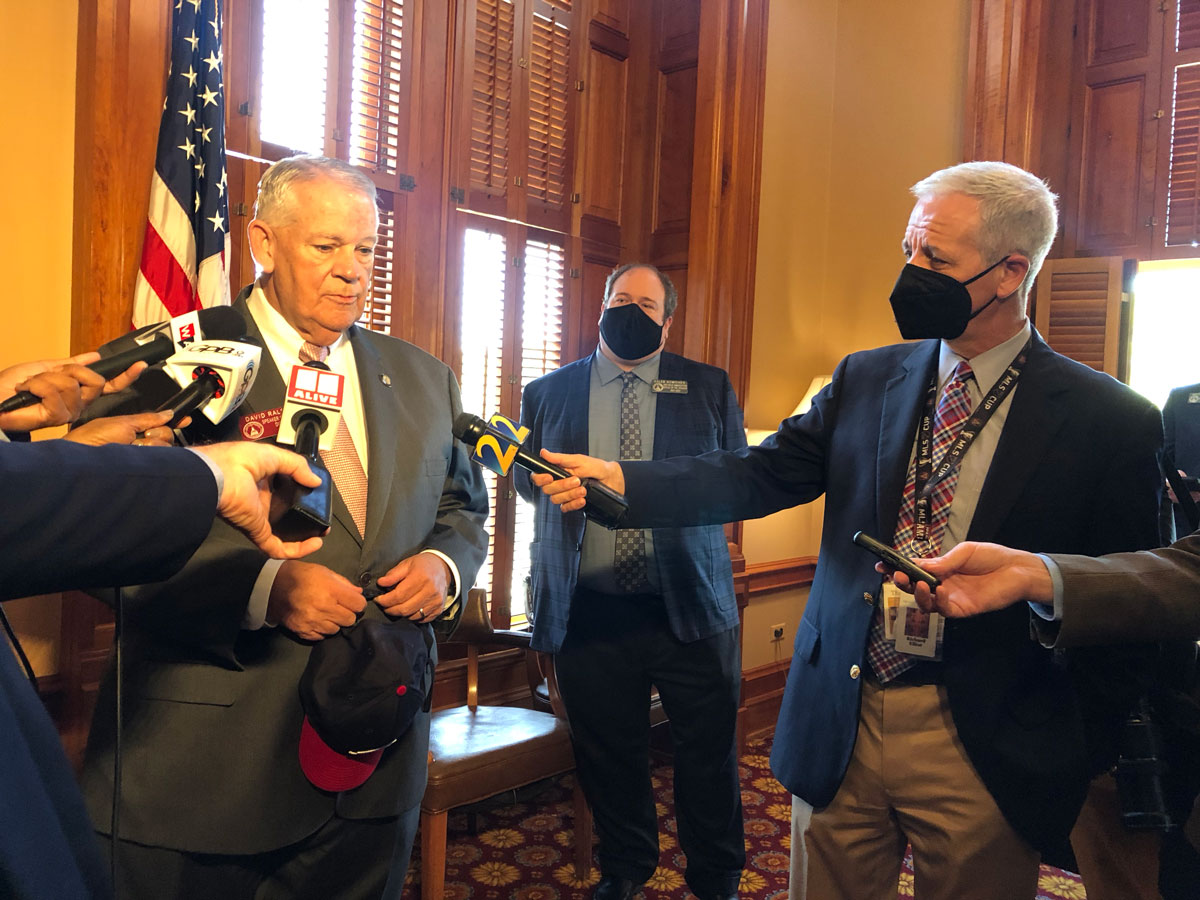

There’s almost no political issue more fiercely partisan than redistricting, but Georgia’s House of Representatives kicked off the procedure last Wednesday on a note of greater bonhomie. “How ‘bout them Braves?” House Speaker David Ralston called from the dais, sporting a wide grin and the World Series winners’ signature red-and-navy baseball cap. Thunderous cheers erupted from both sides of the aisle.

For a few moments, at least, everyone was on the same team.

But that comity is sure to dwindle quickly, as the House and Senate dig into one of the most complicated and momentous responsibilities of a state legislature: the once-a-decade redrawing of electoral maps based on new census data, which determine the boundary lines of seats in the State House, the State Senate, and the U.S. Congress. Republicans, who control both state chambers and the governorship (known in political circles as a trifecta), have little incentive to draw maps favorable to Democrats. But the minority party and voting rights watchdog groups hope that intense public scrutiny and the threat of gerrymandering lawsuits will help to produce something of a compromise.

Photograph by Rachel Garbus

The redistricting process always begins with a slew of proposed maps from groups both inside and outside the legislature. The night before the special session opened, Republican-led redistricting committees for the House and Senate publicly released their proposals, while Georgia Democrats shared their own proposals on October 27. Meanwhile, Georgia Unity, a coalition of nonpartisan organizations that includes the NAACP and the Urban League of Greater Atlanta, proposed a slate of maps that they said reflected Georgia’s growing diversity. There are any number of ways to draw electoral maps, and anyone can design them—the Princeton Gerrymandering Project computer-generates millions when analyzing how much the boundaries of a state’s final map can be statistically attributed to gerrymandering—but the redistricting committees decide which of those maps to consider, making it unlikely that either the Democrats’ or Georgia Unity’s will gain traction.

After that, there’s not much more Democrats can do but watch their GOP colleagues seal the deal. “It’s a simple majority vote,” explained Democratic Representative Josh McLaurin, District 51. “I don’t know that there’s much to hope for—you hope the majority’s going to follow the law, and then you see whether they do or not.”

As of Friday, over criticism that they were rushing the process, the Georgia Senate was moving towards a vote on their map, which cements a Republican majority as expected, but does add one Democrat-leading district. Shortly afterward, accusations of gerrymandering began pouring in. “Current maps are focused on manipulating district lines,” The Georgia Redistricting Alliance, a voting rights coalition, tweeted on Friday. “We need fair maps.”

Gerrymandering—the manipulation of electoral lines for partisan advantage—is not new. The term was coined in 1812, when Massachusetts Senator Elbridge Gerry proposed a set of redistricting maps heavily favoring his Democratic-Republican party, whose shape reminded political opponents of a salamander—or rather, a “gerrymander”. Since then, gerrymandering has been a regular thorn in the side of American democracy, with both parties taking advantage of map-making for political gain. Partisan redistricting relies on methods like “packing,” putting many minority-party voters in just a few districts, and “cracking,” splitting up politically like-minded neighborhoods and placing the segments in districts that heavily favor the other party.

In the last ten years, however, gerrymandering has become much more sophisticated, thanks to high-tech modeling and precision polling, and more threatening to the democratic process in its dilution of minority-party voters’ power. In 2019, a three-judge panel in North Carolina threw out that state’s heavily gerrymandered maps, noting how the Republican legislature had diluted Democratic voting power with “surgical precision.” Yet even as the impacts of gerrymandering have become more evident, fierce partisan divides are motivating trifecta states across the country to secure political power through manipulated maps, and the federal government and the justice system seem unable—or unwilling—to intervene.

On top of intense concerns about gerrymandering, this year’s redistricting process is already particularly fraught. For one thing, the Covid-19 pandemic delayed the U.S. Census Bureau’s release of the 2020 data by several months. And once that data arrived in August, it revealed demographic shifts that spell trouble for Republicans’ monopoly on political power. Large growth in Georgia’s Black, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander populations have made Georgia a roughly 50 percent non-white state, a trend that, given the racial composition of political parties, is already favoring Democrats, who clinched both U.S. Senate seats in a squeaker runoff this January. And since 2010, Georgia’s population has ballooned to 10.7 million, adding over a million new residents and landing Georgia in the top five states for population growth. Yet nearly all that growth has clustered in metro areas, while rural districts, following a nationwide trend, have been steadily hemorrhaging voters.

Population shifts mean that district lines will need to follow suit; Georgia Republicans know that no matter how they draw the maps, some Republicans will end up on the chopping block. “It’s no secret that Republicans are stronger in rural Georgia than they are in metro areas,” Speaker Ralston, who represents District 7 in North Georgia, noted after Wednesday’s opening session. “That’s where much of the population loss has occurred, so we have to account for that.” To that end, the House Republican Caucus released a proposed map on November 2 that would sacrifice six Republican seats, while carving out safer Republican districts in rural areas they hope to hold onto for the next decade.

Photograph by Rachel Garbus

While demographic change has favored Democrats, Georgia Republicans are benefiting from a wholly different transformation: a more conservative U.S. Supreme Court. Once upon a time, the Supreme Court robustly championed voting rights protection, but a conservative ideological pivot, decades in the making, has methodically dismantled much of those protections in favor of state’s rights. In 2013, the conservative majority, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, overturned a key section of the 1965 Voting Rights Act in Shelby County vs. Holder. That ruling effectively nullified the pre-clearance statute that required states with a history of racial discrimination to submit any voting procedure changes to the U.S. Department of Justice for review. That means, for the first time in over 50 years, the Georgia Republican trifecta will not be subject to federal oversight when implementing their district maps. And while the Voting Rights Act still prohibits racial discrimination, the Supreme Court gutted another section this year in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, making it exceedingly difficult to demonstrate that discrimination in court.

“It really is a fundamental change in judicial attitude,” remarked attorney Emmet Bondurant, partner at Bondurant, Mixson & Elmore and a litigator for Common Cause, a watchdog organization that frequently takes conservative legislation to court. Bondurant has watched that attitude shift in real time: in 1963, he argued in front of the Supreme Court in the landmark districting case Wesberry v. Sanders, arguing that U.S. Representative districts ought to be apportioned according to population size. The court agreed with him in a 6-3 decision, holding that every district in a state must represent the same number of people. It was a huge win for the principle of “one person, one vote”, and a hallmark of the Supreme Court’s judicial philosophy under Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Bondurant was just 26 when he argued Wesberry. Decades later, in 2019, he was back at the Supreme Court, arguing against the state of North Carolina over its gerrymandered district maps (the same maps that judges, in another court, had excoriated for their surgical precision). But the Supreme Court’s composition and ideology had shifted; the conservative majority held 5-4 in Rucho v. Common Cause that gerrymandering was a political question beyond the purview of the courts, thereby giving the green light to maps that dilute the power of the minority party, possibly forever. The timing of the case was crucial to the outcome: freshly minted Justice Brett Kavanaugh had just taken his seat, replacing Justice Anthony Kennedy, one of the court’s last swing votes.

Reflecting on the voting rights cases that bracket his career, Bondurant thinks we’ve seen the end of a judicial system that expands ballot access by the power of the federal government. “In the Sixties, the Courts [had the] view that their obligation was to make democracy work better, not worse. This Court has the opposite attitude: their role is not to make things better, but to give free reign to state’s rights.” The privileging of states’ rights—embraced by conservative judges and the Republican party alike—undergirds many of the lightning-rod issues currently dividing America, from abortion to open-carry gun laws. The last spate of Supreme Court decisions on voting rights are a clear indication that, for conservatives, protecting states’ rights is a priority on par with the equal power of every vote.

Back under the Gold Dome, Speaker Ralston was dismissive of suggestions that Georgia Republicans would take advantage of the lack of oversight to push through unjust district maps. “There’s a building right over there called the Federal Courthouse,” he noted. “The courthouse door’s open if people have substantial issues with the maps.”

Still holding his Braves hat, Speaker Ralston was more excited to talk about the recent World Series victory. “There’s something about this year,” he called gaily on his way out of the House chamber.