Photograph by Mike Jensen

Stepping off of the elevator onto the second floor of the High Museum of Art’s Ann Cox Chamber Wing, nearly 150 gold-painted arms raised with the Black Power fist are suspended in the air. Connected by cables, they form a shape that looks like a mix of Newton’s Cradle and a helix of DNA. The piece by Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Glenn Kaino is called “Bridge,” and was the artist’s first collaboration with Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith. On October 16, 1968, Smith, along with bronze medalist John Carlos, made headlines when he raised his fist in solidarity with the civil rights movement at the medal ceremony for the 200-meter race during the Summer Olympics in Mexico City. “Bridge” is meant to convey the same message as Smith’s protest 50 years ago—to unite all people in the fight for equity and human rights.

Photograph © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

The 100-foot long piece, along with memorabilia from Smith’s life, drawings contributed by students from across the country, and new sculpture and drawings by Kaino and Smith make up the High’s latest exhibition, “With Drawn Arms,” which opened September 29 and will be on display through February 3.

Kaino and Smith first met in 2012 when they were introduced by a mutual friend who Smith coached at Santa Monica College. Kaino flew to Stone Mountain, where Smith resides, and noticed his home was filled with images from 1968. Smith played a video of the race for Kaino, narrating what was happening in his mind at each moment. Inspired, Kaino offered Smith the opportunity to bring his protest into the present by casting his arm into a work of art.

“I often work with subject matter related to change-making, civil rights, and activist work,” Kaino says. “The whole project is about using art to deconstruct and help us understand how images and symbols are made, and the contributions of symbolic protest.”

In that vein, “Bridge” detaches the fist in order to “separate the symbol from the man,” Kaino says. “Tommie and I [are] using his arm to connect issues of the past with issues of the present.”

Photograph by Mike Jensen

Michael Rooks, the High’s contemporary art curator, has long been a fan of Kaino’s work, and the two began talking about collaborating back in 2013. A renowned artist, Kaino was selected in 2012 by the U.S. Department of State to represent the United States in the 13th International Cairo Biennale in Egypt, and was included in the 2004 Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art and in the 12th Lyon Biennial in France. Neither had any idea how relevant the work would be today.

“Given that Atlanta is the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement, this exhibition is a perfect fit for us,” Rooks says. “Everyone knows this gesture. Tommie didn’t invent it, but that moment in ’68 was televised around the world and seared it into the collective image bank. It’s become a meme in a way. By having an exhibition that explores this gesture, this person, and this historical moment in a way that is expansive, I hope we’ll allow people to think about it in a way that’s less binary.”

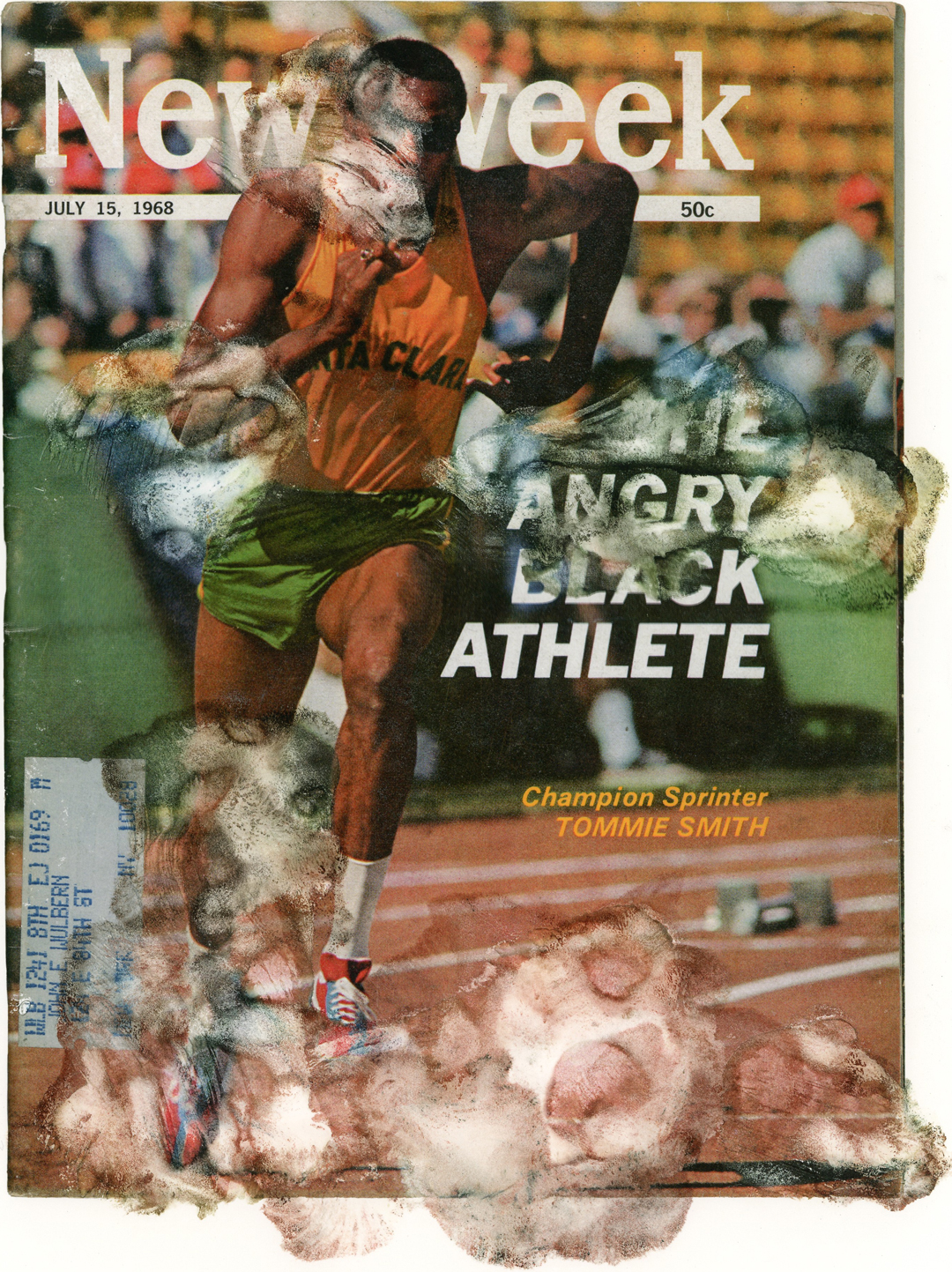

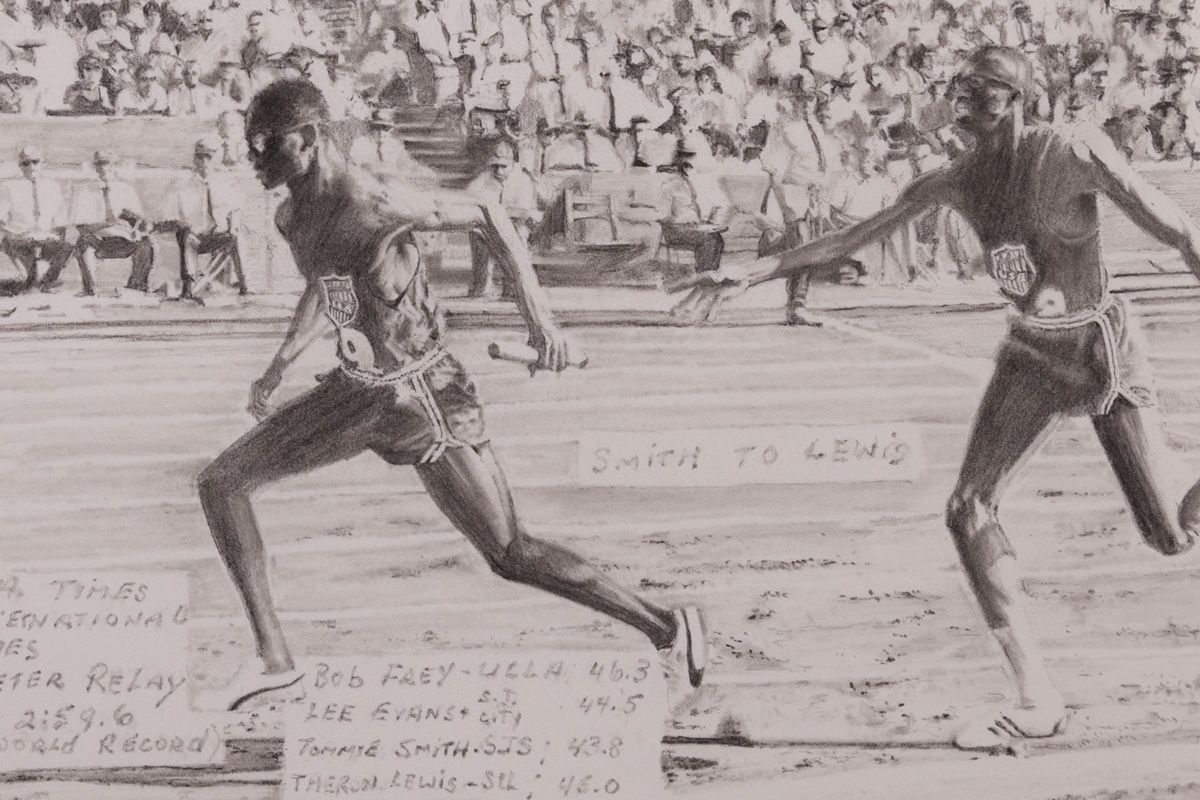

Smith was a senior at San Jose State University when he competed in the 1968 Olympics, and had already broken seven world records before the games began. In the heated political climate of 1968, Avery Brundage, then head of the International Olympic Committee, stated the games were not a place for political protest and urged athletes to refrain from any such activity. Despite the warning, Smith and Carlos knew they needed to speak out. They wore African beads around their necks and the patch of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, a civil rights organization they helped establish, on their uniforms. Peter Norman, the Australian silver medalist in the 200-meter race, showed his support by wearing the patch on his uniform as well. After the protest, the IOC banned Smith and Carlos from competition. Norman, who died in 2006, was not officially banned but was never picked to represent Australia in the Olympics again.

“I had no idea how I would be remembered, but I knew I had a responsibility,” Smith says. “It was only decided moments before I got on the victory stand what I was going to do. I told [Carlos and Norman] what I was going to do, and it just so happened we were going to do the same thing.”

Fifty years after that historic moment, athletes today still face consequences for speaking out against inequity—inside and outside of the arena. When former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick kneeled during the National Anthem in 2016 to protest police brutality against unarmed black men, he was released from his contract. The wife of NFL player Antonio Cromartie also said publicly she believed he was released from the Indianapolis Colts for the same reason. Despite a large amount of controversy and calls for fines and bans, several NFL players have continued to kneel and otherwise protest during the National Anthem. In September, a Nike ad featuring Kaepernick with the verbiage “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything,” both boosted the company’s sales and sparked incidents of people burning their shoes and vowing to boycott the brand. Here in Georgia, Truett McConnell University in Cleveland ended its school bookstore contract with Nike after the Kaepernick ad was released.

“Colin Kaepernick is using a platform that was used 50 years before for the same reason: human rights,” Smith says. “What Kaepernick did and what the athletes did in 1968 are related, and they’re going to continue to be related.”

Photograph by Mike Jensen

Kaino hopes that visitors to the museum will be inspired by the often overlooked nuances of protest.

“Hopefully this show helps us to understand that symbolic protests are generated from a much more complicated set of ideas, rather than being able to be flattened in a moment by saying it’s anti-patriotic,” Kaino says. “Tommie Smith bowed his head in prayer as an attempt to communicate to the world that he is a religious man. He got off of the podium at a 90-degree turn to the right to show to the world that he was a patriot. I would guess that [with] Kaepernick or any other protest, there is the same depth of thinking.”

Update 10/2/18: This exhibition was originally slated to run until January 6, but was extended to February 3. The story has been updated to reflect that.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)