Photograph courtesy of Atlanta United

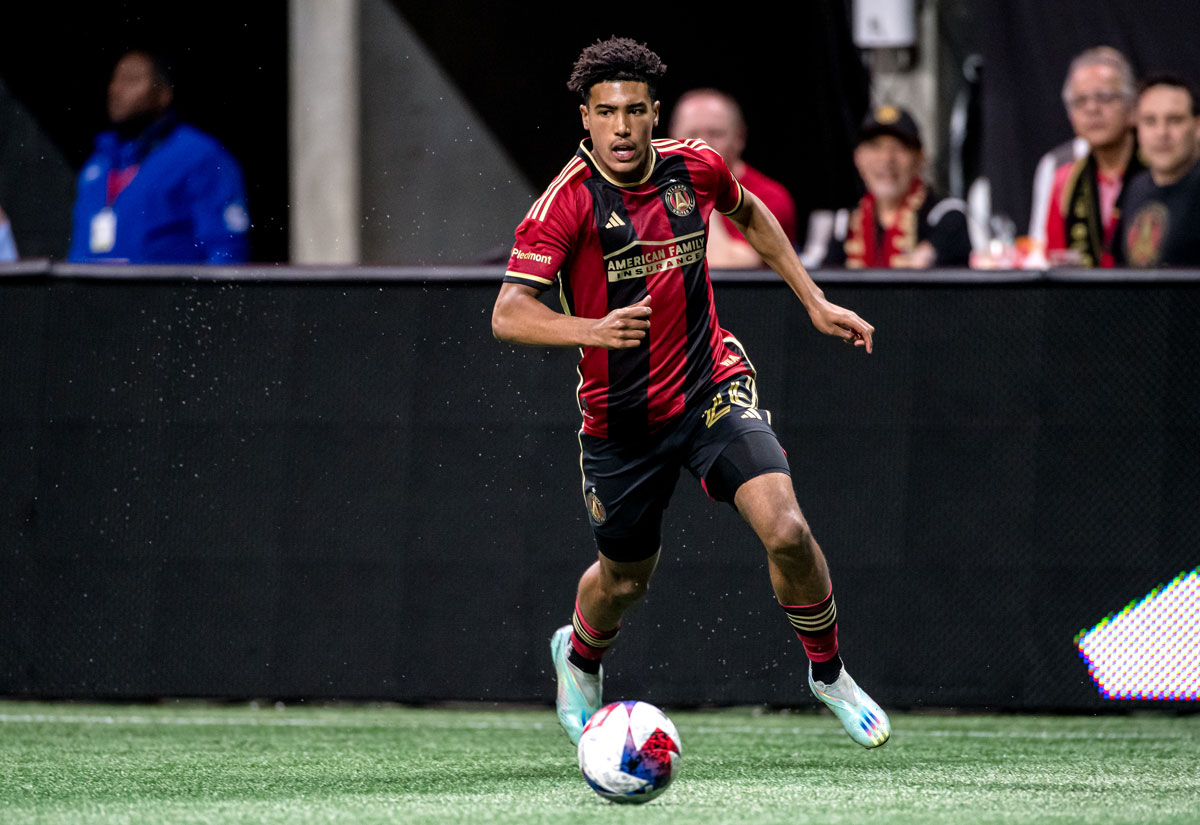

Caleb Wiley was able to make good on his childhood career plan. “On those elementary school things where they asked what you want to be when you grow up, I always wrote ‘professional soccer player,’” says Caleb, who attended Morningside Elementary here in Atlanta. It’s not what you’d call a practical aspiration—men’s high school soccer players have a 0.08 percent chance of going pro per a report from the NCAA—but extraordinary talent makes room for the impractical. In July 2020, at 15 years old, Caleb made his debut with Atlanta United 2, becoming the club’s youngest player to appear in a professional game.

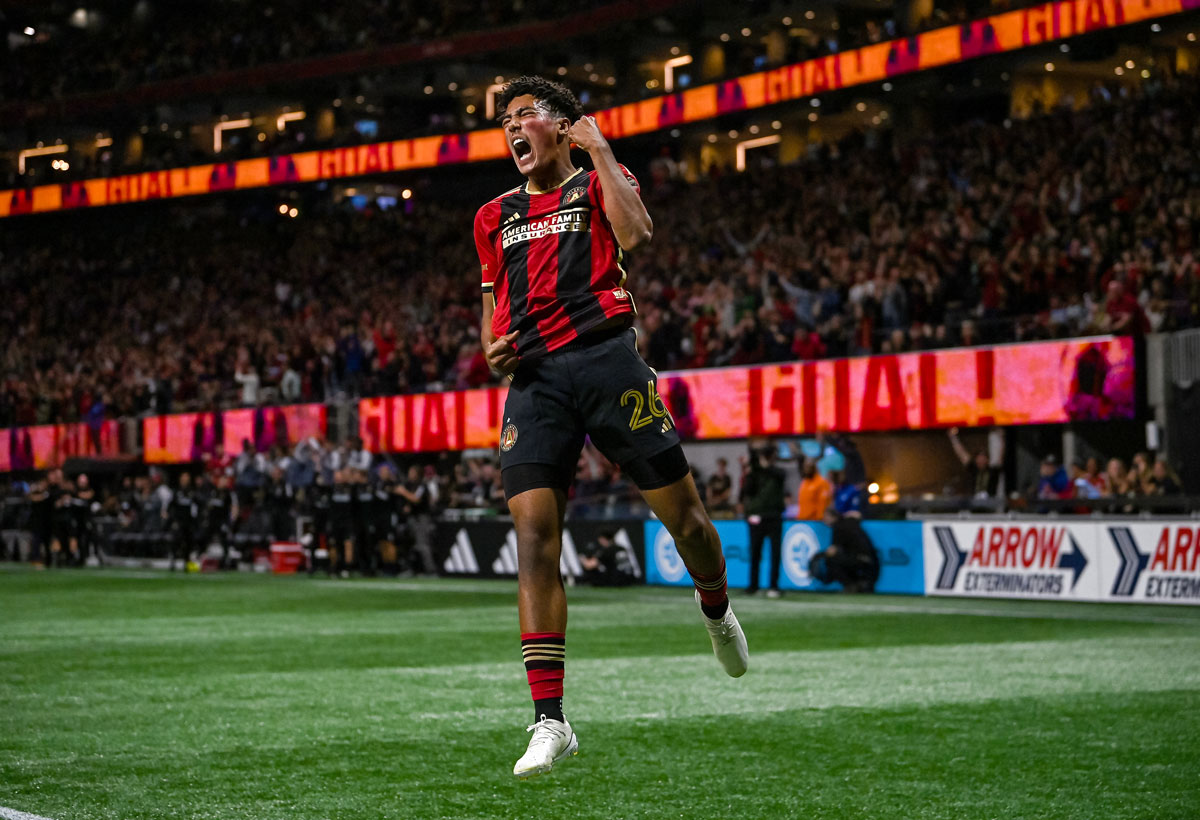

Less than two years later, he moved up to the main squad, where he’s now the starting left back—and lately, a crucial goal creator. In March, Caleb made headlines in a match against Charlotte FC, scoring twice and assisting forward Luiz Araújo in a third. “We think [he’s] going to be a great, great player,” Coach Gonzalo Pineda told Dirty South Soccer after the match. “Just a kid from Morningside!” Atlanta United crowed. With three goals and two assists so far this season, Caleb’s helped make this one of the strongest starts ever for Atlanta United; the club is currently in third place. And the good news just keeps coming: in April, the U.S. Men’s National team called up Wiley, who’s now 18, for a match against Mexico.

“It’s truly the best feeling,” Caleb told me recently at Atlanta United’s training center, speaking of the team’s recent victories. “My heart just gets so big—there’s so many emotions.”

Caleb’s success is Atlanta’s, too. He was part of ATLUTD’s first crop of kid players, earning a spot on the U-12 team when the club launched in 2016. “Caleb’s one of the most quietly motivated kids I’ve ever seen. He’s nonstop—wants to train, wants to get better,” says Matt Lawrey, director of Atlanta United Academy, who coached Caleb’s U-12 team. “He’s been a joy to work with from the beginning.”

A quiet, disciplined player, Caleb showed uncommon athletic promise almost as soon as he could walk, says his dad, Chris Wiley. “He was probably three or four years old where we really noticed how good his balance was,” he told me. “From Razor scooters to bicycles . . . that’s when I thought, Okay, he’s pretty good at this.” Caleb dabbled in several sports, including basketball and lacrosse, before zeroing in on soccer. “I think I was maybe nine or ten when I started realizing soccer is what I truly love,” Caleb says. “That’s when I really went for it.”

Photographs courtesy of Chris Wiley

Like many American kids, Caleb’s soccer career began at the YMCA. He was eleven when the Wileys got the call about Atlanta United. “The timing was perfect,” Chris says. After preliminary tryouts, the academy held two training sessions for about two hundred U-12 boys from across the Southeast; Caleb clinched one of 30 slots. “From that point on, he was playing with equally talented kids, but we just watched him keep progressing,” his dad says.

Soccer academies like the one Atlanta United hosts aren’t your typical after-school sports program. Between morning practices and traveling to international matches, attending traditional high school isn’t always possible; the academy offers an on-site school and online courses designed around training schedules. The model doesn’t work for every young player, many of whom drift to other interests, but Caleb thrived in the demanding environment. “Even today, his Saturday afternoon is watching probably six hours of soccer,” his dad laughs. “Caleb’s personality just made it really easy.” But enjoying the game is always a priority: “Since he was little, I tell him before every game, ‘Have fun, play hard, and have more fun,’” Chris says. “We just try to give him the support and the pathway.”

Part of that pathway is proximity to a professional club: Caleb told me nothing stoked his hunger as a tween like seeing Atlanta United win. He was on the pitch as a ball boy when the Five Stripes won the MLS Cup in 2018. “They had us on the parade bus through the city—I’ll never forget that day,” he told me. “Just riding through Atlanta, thousands of fans cheering—that was better than anything.”

Photograph courtesy of Atlanta United

Caleb’s success—along with a number of other academy players—reflects professional soccer’s rapid growth in the U.S. and deepening investment in the development of young talent. Atlanta United Academy has already produced an impressive number of professional and collegiate athletes, including Atlanta United first-team players Machop Chol, Noah Cobb, Efrain Morales, and George Bello, among others. Many others earn college scholarships or play for Atlanta United 2.

Caleb and his fellow academy graduates all joined Atlanta United as so-called Homegrown Players, a Major League Soccer program that’s been instrumental in growing club-based training centers. Introduced in 2008, the Homegrown Rule lets MLS teams sign athletes trained through their academy directly onto their first team without going through official channels like the MLS SuperDraft. More importantly, homegrown contracts aren’t included in the overall salary caps that limit how much teams can pay their players, freeing up money for marquee international talent or expensive trades. This rule incentivizes teams to sign more homegrown players—and to nurture the academies that produce them.

“It’s a way that professional teams make sure they’re giving back to their own community, raising their own players from within,” explains Lawrey, the academy director. The homegrown program has been crucial to developing the youth-to-pro pipeline in American soccer, which for decades lagged behind the professionalized training programs common in Europe and South America. Those pipelines have produced some of the world’s greatest soccer players: in 2000, FC Barcelona brought a 13-year-old Argentinian with a growth hormone deficiency to train with their academy in Spain. His name was Lionel Messi.

The Homegrown Rule has paid off handsomely for MLS, which is seeing its domestic talent pools grow, sending up more young players to national teams. For the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, U.S. coach Gregg Berhalter’s roster included 18 former or current MLS players, six of whom were homegrown. “There are amazing players come through these MLS academies,” Lawrey says. “These are really quality programs, and quality players coming through at young ages.”

For Atlanta United Academy, the success of Caleb Wiley and other homegrown pros is more than just proof the program is working: they’re now role models for a new generation of aspiring soccer players. “Once the kid down the street makes it, it just becomes so real for the rest of the kids in that community,” Lawrey adds. “It’s not just some far-off vision.”

For Caleb, making it professionally is both a wild dream fulfilled and one more step in what will hopefully be a long career. He hopes to represent the U.S. at the 2026 World Cup—some of which will take place at Mercedes-Benz Stadium here in Atlanta—and ultimately play in Europe.

But right now, he’s proud to play for Atlanta, alongside some of the players he started out with as a kid. “There are a bunch of us from the U-12 team that are on professional contracts now,” he told me. “It’s just so cool that we’re all out here, doing what we love.”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)