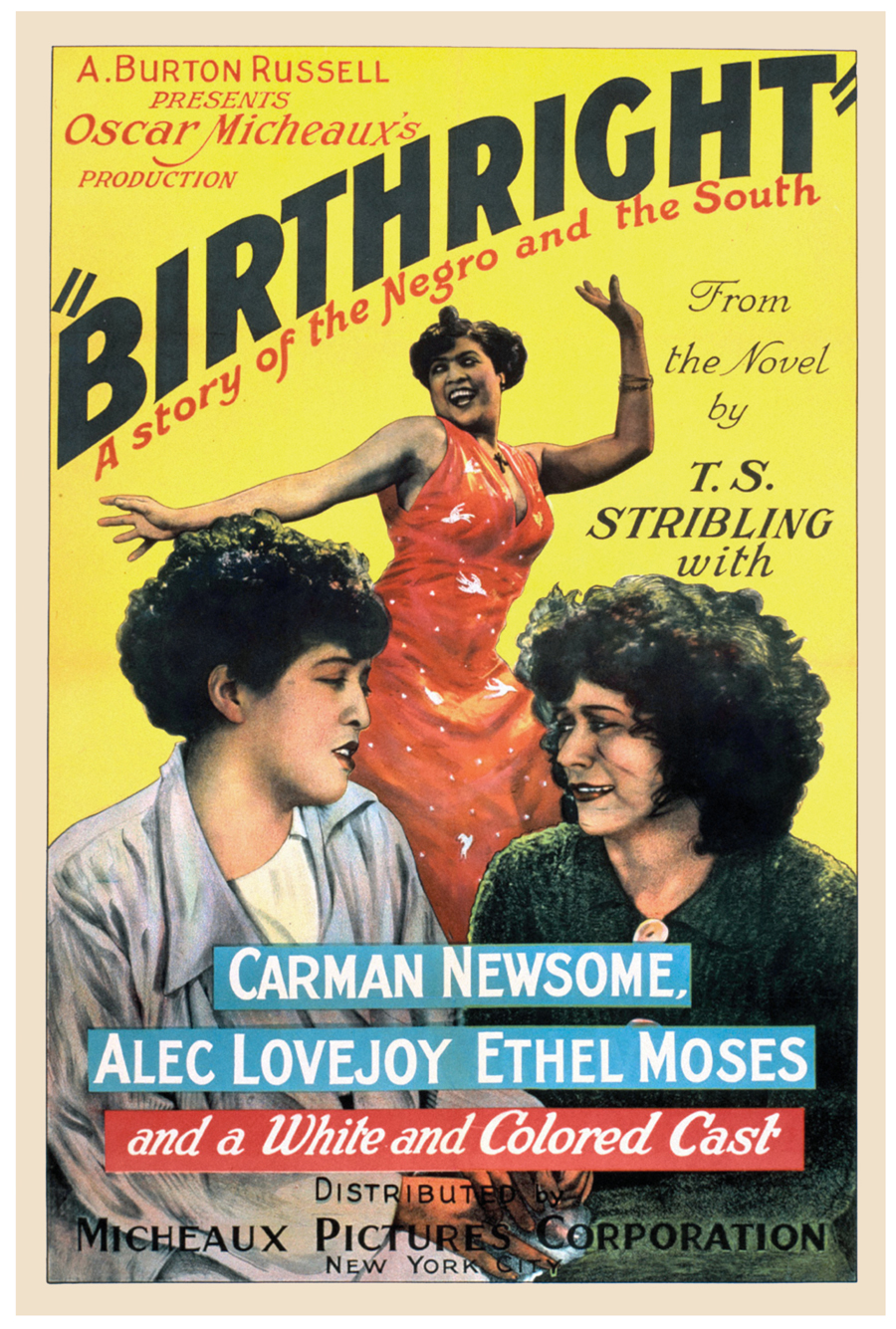

Courtesy of Kino Lorber Inc.

Metro Atlantan Bret Wood has spent his career exploring the highs and lows of cinema. As a longtime DVD and Blu-ray producer for independent film distributor Kino Lorber, Wood has shepherded the DVD releases of high-brow disc sets like Edison: The Invention of the Movies, as well as such Euro-trash schlock as Daughter of Dracula. But with video sales in decline thanks to competition from streaming services like Netflix and Amazon, Wood had gotten used to spending much of his time helping produce a flood of cult and exploitation box sets that keep the company profitable.

That’s why his most recent project—Pioneers of African-American Cinema, a five-DVD box set released in July—has been such a welcome surprise, garnering a resume’s worth of superlatives from such publications as the New Yorker (“a landmark in the history of the art form”) and the New York Times (“From the perspective of cinema history . . . there has never been a more significant video release”).

“The runaway press attention for this set has been amazing,” says Wood, sitting at his home editing bay in College Park. “It’s the most I’ve seen for one of our releases.”

The project came about thanks to a rare foray into crowd-funding. A former Kino colleague who had decamped to Kickstarter suggested that his old company use the website to raise funds for an ambitious film restoration project. Wood’s bosses were skeptical that they could raise enough to help produce a DVD box set but decided to give it a shot. Wood’s pitch—a compilation of films made for black audiences from the silent era through the mid-1940s—was selected and the project was given 30 days to raise $35,000.

When the Kickstarter campaign launched in February 2015 and pulled in more than $50,000, Wood was allowed to expand the set from four discs to five and include an 80-page booklet filled with photos and essays. “I really had no one looking over my shoulder—especially after I had 50 grand in the bank,” he says.

Wood began the project by bringing on composer Paul D. Miller—better known as recording artist DJ Spooky—as executive producer and public spokesman, and hiring film scholars Jacqueline Stewart of the University of Chicago and Charles Musser of Yale to advise him on which films to include. And he started calling the Library of Congress, George Eastman Museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and other prominent film archives to look for material.

“I wanted to make the set as all-encompassing as possible, to include cornerstones of African American cinema, like Body and Soul with Paul Robeson, as well as movies that few people had seen before,” Wood says.

Courtesy of Kino Lorber Inc.

Body and Soul, a silent from 1925, is the best-known of eight features included in the set that were directed by Oscar Micheaux, widely credited as the first black film auteur and known for tackling uncomfortable subject matter such as lynchings, “passing” as white, and religious hypocrisy. But not all of the films in Pioneers address social issues. The set also includes musicals, comedies, crime dramas, and even a cowboy film with an all-black cast featuring the popular Bronze Buckaroo. The connecting thread is that all of the films were made for black audiences and tell stories from an African American perspective.

Over the next year, Wood and his cocurators dug up obscurities like The Flying Ace, a low-budget 1926 air adventure in which no planes are ever seen leaving the ground, and Hell-Bound Train, an hour-long “filmed sermon” showing sinners on their way to inferno that was made by husband-and-wife team James and Eloyce Gist to be shown not in theaters but in black churches.

Pioneers finally weighed in at almost 20 hours of features, interviews, and trailers. Wood is especially proud of the inclusion of “lost films,” such as a 15-minute segment, narrated by novelist Zora Neale Hurston, documenting a 1940 Gullah religious service. There are also fragments of other movies long since lost to history.

“No one ever releases these incomplete films, so this is the only way most people will have to see them,” Wood says. One film fragment was in such terrible shape that he wasn’t going to include it, but changed his mind. “Seeing a film melting in front of your eyes will help people understand why film preservation is so important.”

Courtesy of Kino Lorber Inc.

Because theaters were segregated, black filmmakers—and a few whites—began making movies exclusively for black audiences. Called “race films,” most were shot on a shoestring budget outside of the Hollywood studio system and, with only a handful of copies made, the films typically ended up existing as threadbare prints, if at all.

“The cultural influence of race films was far out of proportion of their economic impact,” explains Matthew H. Bernstein, chair of Emory University’s Department of Film and Media Studies, who made a survey of Atlanta’s black movie theaters before desegregation. At the industry’s height in the 1930s and 1940s, the city had eight black theaters, of which the most popular were the glitzy Bailey’s Royal in the Oddfellow’s Building on Sweet Auburn and the enormous Eighty One Theatre on a downtown site now occupied by a Georgia State University office building.

Because Atlanta was a transportation nexus, its black theaters were able to get Hollywood blockbusters, which meant that filmmakers like Micheaux were forced to compete with the big studios for bookings, Bernstein says.

“The Pioneers of African-American Cinema set is a huge boon to educators, historians, and anyone else who’s interested in the subject,” he says. “There have been previous efforts, but nobody’s put together a collection of this size with such good condition.”

Courtesy of Kino Lorber Inc.

Besides universal acclaim from critics—including a laudatory cover blurb from Martin Scorsese—Pioneers has enjoyed brisk sales to classrooms, college libraries, foreign TV channels, and even some of the same streaming services that have precipitated the decline of DVDs. Which is good, since the final cost of producing the set edged close to six figures.

Kino president Richard Lorber hails Pioneers—and its crowd-funding origin—as a breakthrough for his company. “Beyond being an important business initiative, this project’s cultural and historic value has made us the most proud we’ve been in years,” he says.

Next up for Kino and Wood is a box set devoted to early female filmmakers of the silent era. The Kickstarter campaign began in October.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)