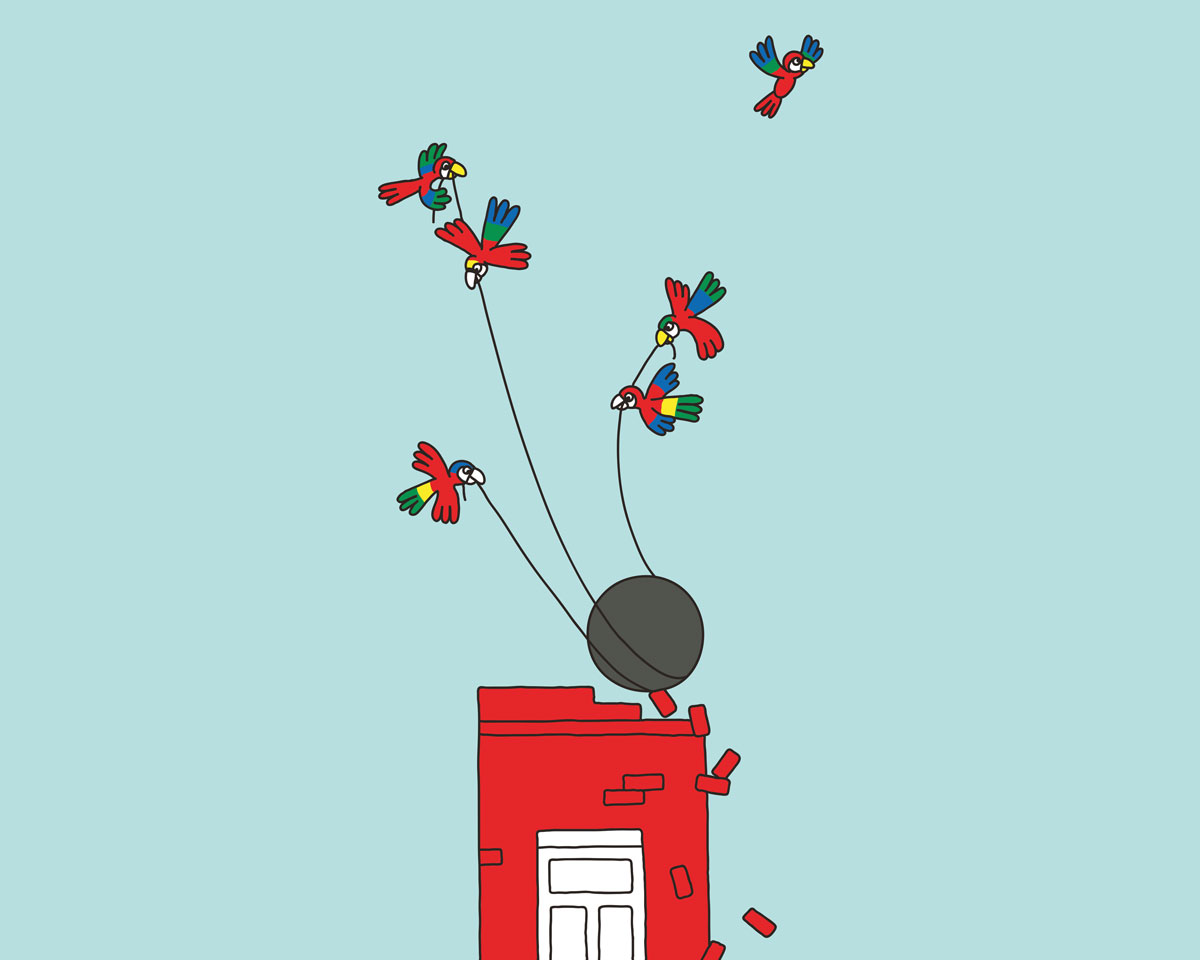

Illustration by Oscar Bolton Green

Goodbye, historic country-music recording studio. Hello . . . Margaritaville? Late last year, workers cleared out the remaining rubble of 152 Nassau Street, a two-story storefront near Centennial Olympic Park where, in 1923, early country star Fiddlin’ John Carson created the genre’s first recorded hit, “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane.” In the building’s place will rise a 22-story tower of—yes—Jimmy Buffet–branded timeshares and hotel rooms. This is just the latest casualty in Atlanta’s endless war against its historic buildings.

Why is Atlanta so notoriously unmotivated to protect its old buildings?

Lax laws, investment-hungry politicians, and demolition-minded developers have made it easy. And it was especially easy after World War II, when white flight and a desire for tax revenue left city officials happy with any kind of investment. In the mid-1980s, then Mayor Andrew Young called two unprotected buildings eyed for demolition—the Margaret Mitchell House and the Castle near the Woodruff Arts Center—a “dump” and a “hunk of junk,” respectively. (They were both spared.)

What has the city done to preserve historic properties?

In 1975, local activists stopped Southern Bell from tearing down the Fox Theatre to build its headquarters by securing a $1.8 million loan and brokering a land swap. The same year, the city beefed up the authority of the Atlanta Urban Design Commission, tasked with surveying and registering historic properties and requests to alter or demolish them. At the time, says Charlie Paine of Historic Atlanta, the commission and its advisory powers—such as determining whether a city or other public project’s proposed design was “appropriate”—made Atlanta quite progressive. In the 1980s, the commission produced a survey of historic Atlanta buildings, including the Fox and the Flatiron Building, and since then has placed historic designations on more than 60 others.

So, what happened?

Yes, federal and local historic designations make tax credits for rehabilitation available for developers. But they can’t protect privately owned buildings in perpetuity or require their upkeep. Plus, city budget cuts over the years left the commission and city planners without the resources necessary to adequately keep discovering, researching, and protecting the fast-dwindling stock of historic buildings. Activists and neighbors are often left scrambling to determine a building’s history only after a demolition permit gets filed. “We’re not proactive; we’re reactionary,” Paine says. No one knew 152 Nassau’s history until after the Margaritaville project was announced and downtown civic activist Kyle Kessler started raising awareness.

How can we save what we have left?

Politicians and the public have to make preservation a priority. The city’s Future Places Project is currently considering how Atlanta’s historic preservation ordinances should change. Developers could also learn more about the incentives that can make rehabbing historic buildings more attractive financially. Or, Kessler argues, they could be required to show how a building is not historic before receiving a demolition permit. Doing so could mean protecting the 99-year-old (and iconic) United Motor Services Building on Peachtree Street designed by prominent Atlanta architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, the future of which is uncertain after its purchase by Emory University in January 2019.

This article appears in our March 2020 issue.