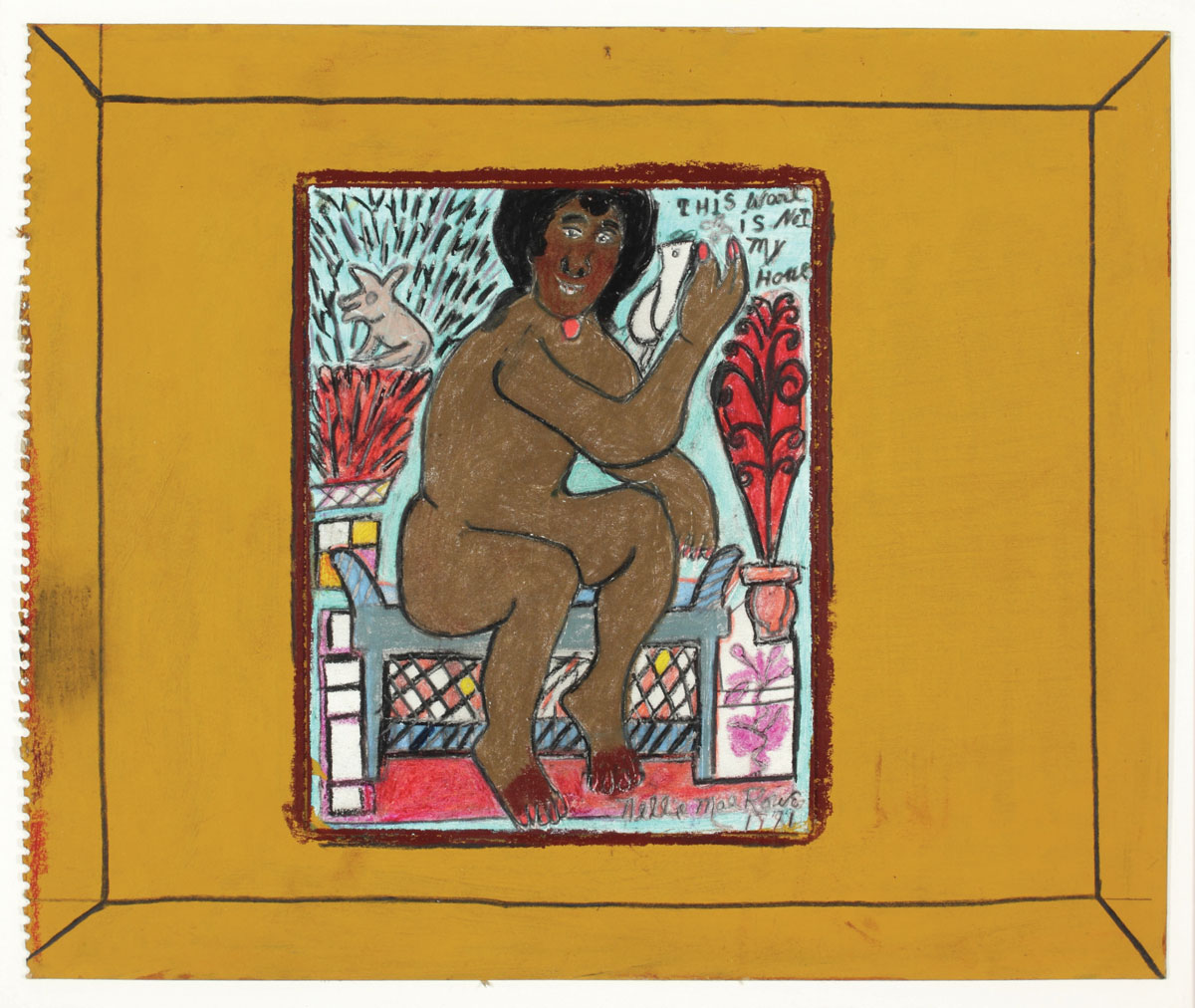

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, T. Marshall Hahn Collection, 1997.105. © Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Every Sunday, Cathi Perry and her sisters visited their aunt Nellie Mae Rowe at her “Playhouse” in Vinings. “Nothing was off limits at Aunt Nellie’s house,” Perry recalls, describing afternoons spent eating pound cake, drawing pictures with crayons on notebook paper, and making jewelry from scrap materials. Rowe turned her home into a world of her own imagination, adorning floor to ceiling and ground to tree branch with masks, found objects, dolls, chewing-gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings.

Passersby often took photos of Rowe’s eclectic home, and she invited them to come inside and explore. Perry says her aunt knew she would be famous one day; by the end of her life in 1982, her work had been featured in exhibitions in Atlanta, Chicago, and New York. The High Museum was the first major museum to start collecting her work and is now reintroducing Rowe to the world in a new exhibition, Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, in the Wieland Pavilion through January 2022.

The exhibition includes 60 of the more than 200 pieces from the High’s collection, including Rowe’s vibrant self-portraits, drawings of flora and fauna, and handmade dolls. In addition, the exhibition will feature photographs of Rowe’s home and art environment taken by Melinda Blauvelt and Lucinda Bunnen in the 1970s.

Katherine Jentleson, the High’s curator of folk and self-taught art, has been working on this exhibition for the last three years but says that the Black Lives Matter demonstrations of 2020 gave her a deeper appreciation of Rowe’s work.

“It made me think more about what she experienced in her own life and what she went through to still claim her own artistic voice, to demand visibility and respect, and to demand dignity for herself and her work,” Jentleson says. “What she was doing was such an act of political and personal will, to not go quietly into her later adult years but to make them the most artistically productive of her entire life.”

Gift of Judith Alexander, 2003.167. © 2021 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

Rowe claimed she was born on July 4, at the turn of the 20th century in Fayetteville. She came to art in her late 60s after the death of her second husband. She’d always had an affinity for artistic expression, but duties on the family farm and then as a wife and domestic forced her to put that calling aside. In the late 1960s, as the Black Arts and women’s liberation movements were bubbling across the country, Rowe seized the opportunity to write her own narrative. She drew her name around the words “really free”—the title of a Bible Society leaflet she’d received in the mail—which inspired the name of this exhibition.

In 1978, she caught the attention of the late Atlanta gallerist and art collector Judith Alexander, who befriended and represented Rowe. Alexander gave more than 150 pieces of Rowe’s work to the High between 1998 and 2003. The High has been displaying Rowe’s art as a part of the permanent collection since 2005, but Jentleson hopes that this exhibition will make her a household name.

“I want people to see each work as its own moment of splendor,” Jentleson says. “I hope she’ll become a part of this moment that we’re living in where Black women artists who were working in the latter part of the 20th century are finally getting the recognition they deserve.”

This article appears in our September 2021 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)