This article originally appeared in our November 2007 issue.

The cars keep coming—sedan, coupe, SUV, SUV, hybrid, van, SUV, truck, station wagon, sedan, truck. It’s midmorning and technically well after the end of rush hour, on a leafy, tree-lined residential street. But this is the ATL, the automotive industry’s bitch, whose car-clogged freeways and surface-street arteries are choking on a diet of pure vehicular cholesterol, and traffic just keeps on coming.

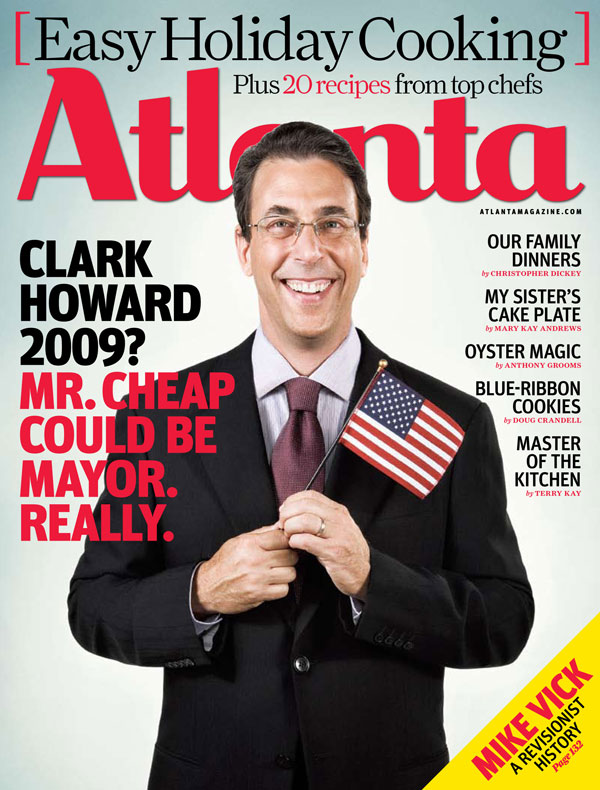

Clark Howard stands by his mailbox. An archetypal nerd, with humidity-curled hair and generic metal glasses, he is instantly recognizable in his wrinkled khaki cargo shorts and clearance rack sneakers. His boyish dimples and unlined face pass for a decade younger than his fifty-two years, though his untucked thrift store golf shirt barely disguises a modest middle-aged paunch. His wife, who calls this outfit the “Clark-iform” says, “If you see him in a suit, someone probably died.”

Clark Howard stands by his mailbox. An archetypal nerd, with humidity-curled hair and generic metal glasses, he is instantly recognizable in his wrinkled khaki cargo shorts and clearance rack sneakers. His boyish dimples and unlined face pass for a decade younger than his fifty-two years, though his untucked thrift store golf shirt barely disguises a modest middle-aged paunch. His wife, who calls this outfit the “Clark-iform” says, “If you see him in a suit, someone probably died.”

Atlanta’s most notoriously frugal resident is in TV reporter mode, trying to demonstrate his locking mailbox (no drive-by postal identity theft for him!). His pared-down crew, a producer and videographer, find a line of sight unobstructed by the stream of fenders, but as the drivers relentlessly whiz along, the whoosh of tires, throb of acceleration, and growl of downshifting trucks keeps drowning out the audio. Finally a sanitation truck stops, blocking traffic long enough for Howard to get his twenty seconds of promo in the can.

A black woman in a white coupe rolls down her passenger window to ask what’s going on. Howard steps forward, smiling “Hi, I’m Clark Howard,” and gets no further because the woman starts screaming, “I love you Clark! I love you Clark!” and bouncing in her seat, turning the whole car into a bobbing and swaying thrill-o-meter.

Howard smiles and waves, his golly gosh gee willickers persona radiating cheerfulness, a trait that drives cynics crazy. There’s nothing thin-lipped and sour about him. How can he be so cheap and so happy? Sure, Howard earned his parsimonious image with tales of prying quarters out of the asphalt in front of oncoming traffic, buying seven-dollar secondhand shirts, naming his slightly irregular pugs QuikTrip and Costco, and planning to leave his body to science to eliminate the expense of a funeral (“they pay for everything!”).

But stingy isn’t the whole story.

Howard has not one but five cars in the drive, he’s recently forked out major ducats for an extensive renovation to his (mortgage-free!) two-and-a-half-acre north Atlanta estate, and he coughs up Westminster School tuition for his daughter. So let’s define our terms. Skinflint? No, that suggests a hoarder who’s found dead of starvation on a mattress stuffed with cash—or Howard Hughes and those soup cans.

Tightfisted? Closer, but still reeking of deprivation.

There’s no argument that Howard is thrifty. But he’s not about doing without—he’s about the deal, whatever the price range. It’s all about copping a bargain buzz, the atavistic thrill of the hunt. If it’s a deal, he’s on it. This guy can get a kick out of finding change in the seat cushions and an adrenalin rush from scoring a sweet deal on a used Jaguar. He’s a thrill seeker, not a miser. Yes, he believes in living within his means, but the means he has to live within have expanded exponentially. This self-professed penny-pincher brings home major gelt extolling the virtues of thrift. And he owes nothing. “We have no debt. There’s no house debt, no car debt, no debt debt. None,” Howard points out happily. With an income “solidly in the seven figures,” he saves 80 percent of his income (15 percent pretax and 65 percent after tax) and has enough left over to maintain a six-bedroom estate here and an oceanfront condo in Florida.

As generous as he is cheap, Howard’s personally bankrolled twenty-three Habitat for Humanity houses, at up to $175,000 a pop, with four more scheduled to start construction next February. At a recent working breakfast at the Comer Cafe in Buckhead, he tipped $9 on a $12 tab. He’ll go to Value City or the Dollar Store to find a deal on umbrellas and buy twenty. “As he’s driving and sees people caught in the rain, he’ll roll down the window and give them an umbrella,” says his wife, Lane Carlock. “It’s like that bumper sticker, ‘Commit Random Acts Of Kindness.'”

“I just hate to see people get soaked,” says Howard.

Another factor that shatters the stereotypical shorthand—Howard’s a risk taker. This is a man who boasts of driving a scooter on the mean streets of Midtown. Who married without a prenup, proof of brass cojones in the divorce-littered landscape of high-stakes millionaire marriages. And he’s a political novice who is seriously considering running for mayor of a city with an overwhelmingly black majority population that hasn’t elected a white candidate since 1969.

Howard’s staff—researchers, producers, an engineer, and interns—convenes in a fittingly no-frills conference room in WSB’s Midtown studios a couple of hours before air time. A water cooler gurgles in the corner between the fridge and sink, and there’s a faint odor of burnt microwave popcorn. The spartan decor consists of some rakishly tilted plaques, a framed Habitat for Humanity T-shirt, and a piggybank.

The staff throws out ideas culled from newspapers, magazines, and the Internet: the resurgence of travel agencies, equity stripping, McDonald’s biofuel trucks, parent coaches. Parent coaches? “It’s $300 for a visit and two phone calls. I think it’s fueled by the ‘nanny’ shows,” explains executive producer Christa DiBiase. “Bah humbug,” Howard scoffs.

A prophet crying in a wilderness of conspicuous consumption, Howard preaches the gospel of fiscal responsibility. Some see him as a garrulous, well-meaning snore who lectures on the value of thrift, brags on his scratch-and-dent appliances, drones on about Roth IRAs, blah blah blah. He’s the last guy you want to get trapped next to at the buffet line. Unless you are caught in the wringer of identity theft, trapped in bad customer service hell, struggling to pay off overwhelming credit card debt, or desperately seeking a flight you can afford. Then you hang on Howard’s every word, even if your mind slams shut at the very mention of percentages and ratios, because Howard knows the way out, and he wants to empower you.

On the way to the WSB News-Talk 750 broadcast booth you pass darkened soundproof rooms freckled with glowing console lights: Kiss 104.4 FM, 95.5 The Beat, 97.1 The River, B98.5. Howard shares studio space with other WSB radio personalities, from rabble-rouser Neal Boortz to crowd-pleasing garden guru Walter Reeves and weatherman Kirk Mellish.

Inside the dimly lit studio, Howard stands in front of his console with one eye on the computer screen that feeds him data on the upcoming calls and access to the Internet, the other eye on the clock that’s ticking down the seconds to air time. The room is crisply air conditioned, really nippy. “Boortz is going through menopause,” someone cracks. Across from Howard a producer, two interns, and a visitor take their seats and tether themselves umbilically to the console with the spiral cords of headphones. Two TV sets are mounted on the studio walls—one tuned to CNBC, the other to CNN—with the audio off and subtitles scrawling across the bottom of the screen.

Producer Kimberly Drobes, checking audio levels on her laptop, slips a scribbled question to the intern, like passing notes in the back of the class. ON AIR lights up, and Howard leans into the intro of his three-hour talkathon. “Welcome to The Clark Howard Show, where I want you to save more, spend less, and not get ripped off.”

Howard opens with an alert on mobile phone “moisture strips” that are supposed to determine whether a phone has been dunked, voiding the warranty. He warns listeners that the strips are inaccurate and tells them how to prove it (“don’t be rrrripped off by your phone company!”). Howard is minimally scripted, just a few bullet points from the staff meeting and a little research support while he’s on air. As he finishes each segment, he floats a paper with the topic’s talking points over the side of a low divider that looks like a sneeze guard. The intern, pen in mouth, types a summary of the show as it happens.

The first caller asks Howard’s opinion of Smart Cars, Euro vehicles so petite that two can fit side by side in a parking space. Howard launches into the pros and cons, using the deliberate, measured cadence of Mr. Rogers. “Can you say en-er-gee-eee-fish-en-cee? I knew you could.” He refers the caller to a website—and that’s typical. He’s quick to point callers to outside resources, including telling them where to buy his books, coauthored with Mark Meltzer, cheaper than they’re sold on clarkhoward.com.

After the caller is off the air, Howard checks his time. He not only takes a consumer pop quiz with every call, he has to wrap it up so each Q&A fits in the packet of minutes allotted between commercials, weather, and news breaks. It’s like playing Beat the Clock while defending a doctoral thesis. He’s deftly fitted this caller’s question and his answer to the allotted time, closing out the call within a fraction of a second. When he’s taping a show, he has wiggle room with recording tricks, like electronically snipping out hesitations, but when it’s going out live, he has to nail it.

In an adjacent room DiBiase is vetting incoming calls, a sometimes emotionally arduous chore she shares with two other producers. The screener has to eliminate callers with questions Howard has recently covered, the weepers, the screamers, the cursers, the ones with heartbreaking difficulties outside the scope of the show. On breaks, DiBiase pops in and briefs Howard on the caller’s plight, summing up the convoluted consumer quandary in a sentence or two. She brings helpful data she’s already pulled from the Internet and says why she thinks he should take the call. As the callers wait on the line, anywhere from two minutes to two hours, she periodically “refreshes” them—industry slang for reminding them for how to behave on air, which in this case means not to give company names, or say where they are calling from, to turn off their radios, and to be ready to go on the air.

By the start of the third hour, the intern is quietly eating Cheez-Its one at a time from a Ziploc. Popcorn makes an appearance. The mics are not as sensitive as TV mics—they don’t pick up the rustle of the bag or the muted crunching. Pitched higher early in the show, Howard’s voice has gotten a shade slower, darker, and raspier as the hours go by. Someone wants to know whether she should do a credit freeze to protect herself from identity theft. Howard methodically gives an explanation an eight-year-old could follow. “I know this sounds complicated and weird, but I’ve got links that’ll explain it. Go to clarkhoward.com, you’ll see my ugly face,” he says merrily. Then he segues to riffing off an ad he sees on CNBC, “Special offer! CALL NOW!!! Combo knife and scissors!!!”

It’s the callers more than Howard and his sound effects who make the show compelling—people beaten down by callous corporate treatment, screwed by misleading salesmen, tempted by shady Internet come-ons. Howard gives straight answers, but he also does a kind of improv, gauging how much levity he can introduce without appearing insensitive—sketch comedy for the fiscally challenged. The next caller asks about buying a timeshare vacation home and Howard gleefully cues up his sirens and exploding bomb sound effects.

Not everyone is laughing.

Howard makes no secret of his dislike of ripoffs, especially corporate contempt for customer service and ethically sketchy business practices, and will call out companies he feels have egregiously misbehaved. His anti-extended warranty stance aggravates electronics store managers, and Realtors seethe as he mocks timeshares. Bankers fume as he rails against equity-indexed annuities that target the elderly, or plugs credit unions. In1992 McFrugal Auto Rental sued over his assertion of bait-and-switch (the case was dismissed). Brokers find his no-load mutual funds advice infuriating. “When Clark got on his no-load kick I thought, ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about,'” sniffs one financial consultant. “There are clients who are not capable, who need advice, and when I advise them, I am deserving of the fee. I changed my radio station then, and it hasn’t gone back.”

Sometimes Howard touts a deal that turns out to be too good to be true. His raves for SunRocket, a cheapo pay-in-advance Internet phone provider (he was a customer) backfired when the company went bust last July. Even though he warned the faithful when SunRocket started laying off personnel at an alarming rate, there was a lot of disgruntled traffic on the “Clark Stinks!” page of his website’s message board after the company tanked.

In some ways, Howard is like a vice squad cop—witnessing the worst of predatory human behavior and the victims’ pathetic outcomes. One of his producers once asked him how come he was so happy all the time. “I just am. I look at everything with a positive view,” he says. “My abiding principle is the only thing that’s the end of the world is the end of the world.”

Howard navigates the Cumberland Costco for a book signing, and he’s cheered like a hero. When strangers flag him down in the parking lot, he rolls down the Scion’s window and greets his fans like he’s never done it before and has been looking forward to doing it all his life. He’s escorted to his signing table in the utilitarian big box store he calls his “home away from home.”

The signing is well-managed by WSB staff, who set up a table, stack books handily, and give people cards to fill out letting Howard know how they’d like their books signed. Howard introduces himself to every person with seemingly inexhaustible patience. His quiet coauthor, Mark Meltzer, executive editor of the Atlanta Business Chronicle, is also at the signing, but he’s mostly ignored by the throng of true believers who want not only books and autographs, but also answers. The crowd shuffles along until they can step forward and spring questions about travel, banking, insurance, or investments. Sure enough, Howard dispenses advice along with autographs.

Poll the fans about why they listen to Howard, and they say he’s honest, he’s ethical, he’s genuine, and he’s smart. Surprisingly, no one mentions cheap—until a trim, well-dressed woman you’d see at Phipps or Whole Foods says she heard on Howard’s show that you can keep a razor blade working for a full year by drying it off after each use. She dries hers with a hair dryer and it works. She told her son and he’s doing it, too. She’s thrilled. That’s a hard-core Howard tip.

Alex Shapiro, the WSB event security guard, stands behind Howard and slightly to the left, watching for the weirdos, the wackos, the nutjobs who might go ballistic. “He never takes money to endorse products. That makes our job easier, but he’s gotten punched,” says Shapiro, whose job is not celebrity bouncer, but rather to remove Howard from a threat—take the bullet, if need be. “He speaks the truth,” shrugs Shapiro. “Some people have too much time on their hands and not enough Thorazine.”

Although Howard is undisputed king of his multimedia domain—The Clark Howard Show, clarkhoward.com, WSB TV consumer reports, newspaper columns, books, e-newsletters, speeches ($15,000 a pop!), a cable show, Get Clark Smart, on magrack.com, and the Team Clark Howard Consumer Advice Center—his media career is, by his own account, a fluke.

After his unexpected retirement in 1987 at age thirty-one (more on that shortly), he stumbled into a guest spot on a WGST radio travel show that morphed into an unpaid weekly two-hour radio travel show of his own. Howard parlayed that job into hosting Cover Your Assets, a personal finances show. “I had no producer, no staff nothing. The business white pages and a dial-up modem was my research team,” Howard recalls. He pulled down a pitiful $150 a week for his daily show, plus the Sunday travel show. With Howard at the helm, Cover Your Assets took off in the ratings, soaring from a 1.1share to an unprecedented 4.0.

By May 1990 he’d added two newspaper columns a week to the mix and still didn’t think he was working until WSB came to court him. “They offered me quite a sum of money;” says Howard. “I was like, ‘Wow.'” He hired a lawyer to negotiate his contract and debuted The Clark Howard Show in 1991. The show was syndicated in 1998 and Howard bought it outright from WSB parent company Cox Enterprises in 2001. “That was very risky. In 2002 I lost money, I worked for less than free. 2003 was a little bit better than breakeven, and 2004, 2005, and 2006 were really good years for the show. At this point it’s very profitable.”

Life is good and the dough is rolling in. So why is he thinking about shutting everything down?

The long driveway to Howard’s home makes hairpin turns through the piney woods. Steep ravines on either side pose their own field sobriety test. The newly renovated front of the two-story house is glass and stone, nice but not grand, solid rather than showy, with a broad stone terrace. Light bounces off the pale wood floors of the entry. The new paint and fresh Sheetrock smells optimistic. A central staircase leads to the top-floor bedrooms, and as Lane gives a nickel tour, it becomes clear how their “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy works. If she brings home a great GOB (going out of business) piece, like her foyer’s brass chandelier (“forty-five bucks!”), Howard hears about it. The plush Oriental rug in delicate creams and neutrals from Moattar in ADAC? “I’d better not say. I was bad,” she gleefully confesses.

A slender woman with shoulder-length auburn hair and an expressive contralto voice, Lane has leveraged her magna cum laude degree in broadcast news from the University of Georgia into a career as full-time actor, including hosting a number of TV shows. Along with being the mother of eight-year-old Stephanie and two-year-old Grant, she runs her own production company and dotes on Howard—she blushes when the ring tone on her cell phone plays “The Clark Howard Theme,” a song composed as a joke following a Q100-sponsored singing contest in which Howard lost to the Braves’s Jeff Francoeur.

Upstairs beneath the eaves, tucked under a ceiling with angles like origami, is the master bedroom. They share a mission-style Costco bed. Her side: a home decor magazine and sunglasses, His side: an economy-size plastic jar of Kirkland store-brand jelly beans and a pair of noise-reduction Bose headphones. The newly renovated master bath has obvious his and hers elements, too. His: a water-saving toilet with two flush buttons—one for liquid only and the other for more substantial sewage. Hers: a Jacuzzi tub and heated towel rack.

Sometimes it’s not about the economy, stupid, it’s a gender thing. He buys cheapo, fall apart toilet paper, but she gets the Charmin. He hates to pay to park (valet, no way!) and drives and walks blocks for a free space. He’s wearing sneakers, she’s in stilettos. Duh. Drop her at the door before you self-park.

Howard sits down for an interview in the small brick and glass garden room, wearing his standard khaki shorts (nine dollars!) and a navy golf shirt with the WSB logo (free!). The kids are playing nearby, there’s banging and sawing and hammering from the construction crew, the electrician and painter interrupt with inquiries, and Howard is utterly unperturbed. Whether he’s shooting a video promo, broadcasting in the studio, signing books at Costco, or sitting on his porch answering ticklish questions about money and politics, he’s the same good-natured guy.

Howard grew up in the slipstream of his affluent parents and older siblings, in a home on Ridgewood and West Wesley, “I am the baby of four kids—and the accident. My sister is 63, my brother is 60, and my other brother is 58. Then oops! Here comes Clark!” says Howard, who claims family members still call him by his nickname, Baby Clark. He had the standard accoutrements of summer camps and private schools; Lovett, Pace, and Westminster. Raised in Reform Judaism, he remembers encountering far more discrimination then than he sees now. “All Jewish boys had to learn boxing so they could defend themselves in high school, but my daughter Becca has never experienced an iota of overt prejudice.”

His maternal grandparents were well-to-do, but his father’s family was often in financial trouble. Howard’s father came home twice from school to see his belongings out on the street because his family had been evicted.

Bernie Howard prospered working for his in-laws’ Lovable Bra company but was fired by his brothers-in-law in 1973.When Howard came home from college for Thanksgiving break, his father sat him down to tell him he couldn’t pay for college after that year. “My father was very worried about how they were going to live and what they were going to live on,” Howard says. Though his family recovered financially (Joy and Bernie Howard opened a successful home accessories business, Howard Unlimited), this sudden reversal of fortune changed Howard’s attitude about money. “When my dad got fired it forced me to fend for myself. It’s part of the reason that I’m so cheap,” he says.

“I think money is about having choice. In a capitalist society when you owe, you’re weak, and when you have, you’re strong. That’s just fundamental economics. It’s never what you make, it’s what you don’t spend,” Howard says earnestly. “People want possessions more than they want control.”

Howard wanted control. He went to work full time at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, took night classes, and graduated in three years from American University in Washington with a degree in urban government.

After graduation, he invested part of a $17,000 trust fund from his maternal grandfather in an electric-car company that went belly up. The rest of the fund went into a cash investment partnership he started with his father, who had worked on the floor of the NY Stock Exchange as a young man. With his profits from stocks, Howard opened his own Atlanta travel agency in 1981in the wake of airline deregulation. Six years later, in the most profitable year in the history of travel agencies, Howard’s chain of independent travel agencies, Action Travel, was bought out by an investor group for $300,000.

“I got out of the travel agency business by luck. I was not for sale,” Howard says. “These guys came to me.” When the deal was done, he asked what position he’d have and got shown the door. “I was shocked. I had no clue. I didn’t realize they were giving me the heave-ho.” At age thirty-one, Howard found himself unceremoniously unemployed, and decided to retire.

“You know, I live on so little money. Frugal lifestyle is key, but let me tell you what else I had. I had real estate: a home on Peachtree Memorial, another house, and a vacant lot. I had a tiny percent of Lovable. When the company was sold in 1986, after tax it was $180,000. Which is very nice money, but I didn’t inherit vast wealth.”

His ambition, hard work, and (mostly) shrewd business decisions had landed him the prize of early retirement, but looking back he feels he missed the fun of college days, of being twenty: “I wish I hadn’t been so driven and worked so hard.” Howard’s first marriage, to Karen, collapsed three years later. He cites growing apart over time as the reason for the split. The divorce was cordial enough where it counts the most—the welfare of their child. He shared custody of his daughter, Rebecca, who is now a freshman at Georgia College and State University and still has her own room in Howard’s house. Still, “going through the divorce in 1990 was very difficult emotionally and financially. Even in an amicable divorce there’s a lot of pain,” Howard says.

That next year, Howard left WGST for WSB, and his on-air stint ballooned from seven to fifteen hours a week. A thirty-five-year-old divorcee, he discovered the joys of bachelorhood over the next few years.

He remembers the exact day he first talked with Lane: June 17, 1994, when he was pulled off the air because of breaking news about a white Bronco cruising down the L.A. freeways with a former NFL player at the wheel. As a newsman took over his chair to do the play-by-play, Howard wandered into the producer’s lounge and started talking with Lane, who was working on the Gary McKee show.

“And it was like ‘BAM!’ Right away. There was magic there,” Howard says.

He proceeded with caution because he’d been told she had a boyfriend.

“We went out a couple of times but it wasn’t a date. I was prospecting. We were ‘predating.’ I didn’t want to make an investment if she wasn’t available.”

Lane was wary because everyone at the station told her to stay away from him. “I had a reputation as a playboy—undeserved,” Howard says.

“They thought I’d be the next stop on the dating route, but he didn’t seem that way to me at all. In fact, he seemed like the most genuine person I’d ever dated. It’s so hokey,” Lane says. “We were at Outback the second or third time we went out, he touched my hand, and it was, ooh”—she gives a little shiver—”electricity.”

”Aw,” says Howard. It’s his turn to blush.

Their early marriage involved a lot of traveling. “It was like jumping on a moving freight train,” Lane says. She used to keep a weekend bag packed, and Howard would call and tell her their (bargain!) destination as she drove to Hartsfield.

When he finally popped the question, it wasn’t, “Will you sign this prenup’?”

“Uh uh. I’m too romantic for that,” Howard says. “I can’t tell you how many men and women through the years have said, ‘I can’t believe you didn’t do a prenup.’ We’ve been married now twelve years and I’ve probably heard that a hundred times at least. I mean constantly.”

“I want names,” Lane interjects.

“They’ll be asking me who should they go to for their prenup or what should be in their prenup and that’s how it comes out. I’ll say I really don’t know, and they’ll say, well, who did yours, and I’ll say I don’t have one,” Howard pauses. “From a practical financial point you should do one, especially if one person comes in with substantially more assets, but I personally can’t do one.”

What does this high-energy family do to relax? According to Lane, Howard never sits still, never watches TV; he even reads the newspaper while he’s jogging on the elliptical. Exercise is Howard’s extra battery pack. “I work out every day and lift weights three times a week. That does a lot to keep me going.”

Travel is a big part of making family memories. Howard likes to visit national parks—any place with wide open spaces and great views—and pedestrian-friendly cities like San Diego, Manhattan, Charleston, and Washington. “We walk and walk and walk some more,” Howard says. Lane looks in every art gallery, and he joins her in the museums. The whole family likes hanging out at their Florida condo, making sand castles and swimming in the pool. Back home in Atlanta, Stephanie rides her Razor scooter and Howard runs alongside pushing Grant in a stroller. Lane plays cards (Kings’ Corner, Hearts, Rummy) with Stephanie, who beats her mom at Monopoly. Howard takes both of his daughters on special annual father/daughter trips.

“We know a lot of very wealthy people who are miserable, so money is not the wealth that really matters. You have to have a certain amount, at least enough to deal with the basics, but as long as you have that, what makes people happy or unhappy is what’s in their hearts. Not what’s in their wallets,” says Howard. “I think that surprises people about me.”

An idea that first surprised people: the buzz about Howard running for mayor. But it’s not such a stretch. Howard’s hero growing up was Atlanta native Martin Luther King Jr. He credits the Nobel Prize winner with being the reason—along with air-conditioning—for the rise of Atlanta to national prominence. Howard also remembers former mayor Sam Massell’s inauguration as an inspiration to him as a young Jewish man. Add to that Howard’s degree in urban government and his decades of consumer advocacy. So when Howard says he’s wanted to be president since he was six years old, running for mayor doesn’t seem so out of the blue.

Lane says she’s always known public office was a possibility. When Howard talked on air about what he’d do if he were mayor back when Bill Campbell was in office, people showed up at WSB with campaign donations. “A political life is something I don’t relish. I value my privacy and wouldn’t want to put my kids through it. But I want Clark to be everything he wants to be,” says Lane.

Howard describes himself as a nonideological “mountain-state Republican”—fiscally conservative and socially progressive. Yet he drives the Democrats crazy by supporting charter schools and vouchers. He’d like poor kids to have a chance to migrate to a better economic status and believes the schools are the greatest gateway in American culture for that. “What’s missing in a public schools monopoly is a sense of urgency—what difference does it make if the school doesn’t get better this year or next year? You’re on the payroll, everybody is still getting their paycheck. It’s the kids that are still passed year to year, without hope and without a chance. That’s why school choice is so important for me.”

But Atlanta’s mayor has no real authority over schools, only a bully pulpit. So what would be at the top of his political agenda? “I’m obsessed with traffic,” Howard says. “Shirley has been the sewer mayor. I’d be the traffic mayor.”

Liberating the city too gridlocked to wait is an ambitious agenda, but Howard’s Achilles’ heel is his lack of political office experience. “When a voter examines Howard’s experience the question will be, ‘What has he ever run?’ Remember that Shirley Franklin emphasized her administrative experience under Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson as well as running the Olympics,” says political insider Michael Jablonski, who has advised former Governor Roy Barnes and Mayor Shirley Franklin, has a law practice concentrating on election law, is general counsel to the Democratic Party of Georgia, and is an instructor in political communication at Georgia State University. “Howard’s intelligence will get in his way because he is a first-time candidate. He will make rookie mistakes. And being smart means that he will probably invent new ones.”

Howard advises listeners who want to buy into a franchise to work there first: “Learn it from the inside out, even if it means emptying trash cans at first.” Yet without running for so much as dogcatcher, he’s applying for Atlanta’s top political job, asserting, “I’d really want to come in clean slate, make my mistakes and then hopefully figure out the best way to do it.”

As the rumors of a Clark Howard candidacy began to swirl last summer, the political blogosphere erupted. Along with a lot of encouraging grassroots support, the discouraging word on the blogs—and behind closed doors with some city bigwigs—is that Howard can’t win because he’s a straight, white male.

Sam Massell, Buckhead Coalition president and former mayor, says, “With the overwhelming majority of Atlanta’s registered voters being African American, it is reasonable to expect the leading black will win in a runoff against the most popular white.”

But Howard believes city demographics are changing and will be split fifty-fifty in terms of actual voters in the next election, due to the population growth fueled by corporate nomads and people moving back into the city to escape heinous commutes. If bigotry drove people out, traffic is driving them right back in.

So will he or won’t he?

Don’t expect for him to decide before 2008. He has a lot to think about. His current schedule permits time with his young children, time he’d lose to campaigning and governing. And he’d have to shut down his media organization, knowing that saying he’s going to run doesn’t mean he’s going to win, and that winning doesn’t mean he’d be effective.

“It’s not like a fork in the road. I’ve got to go pave a whole new road when I’ve already got a superhighway. I’ve got all this going on that I’d have to chop off at the knees. Anybody in my industry thinks I’ve lost my mind to even remotely consider it.”

If Howard does decide to run, the pundits have some suggestions. “There’s a good bit of poverty in the city and a gap between the haves and the have-nots. A mayor needs to address this,” says Dr. William Boone, professor of political science at Clark Atlanta University, “A mayor needs to be able to convince the state and surrounding counties to support Grady [Memorial Hospital].”

“I would hope that a Mayor Howard would focus on quality of life issues,” Jablonski says. “He should recognize that Mayor Franklin leaves the next mayor with an excellent foundation upon which a visionary can create an amazing city.”

“He is so popular and successful in his present public role, the only advice I would offer, if he runs, is to maintain his persona and don’t try to out-politic the politicians,” says Massell, Atlanta’s last white mayor.

“Since this started I’ve noticed two things, stark as they can be,” Howard says. “People who are insiders feel no hope and think I am wasting my time. People who are outside the political process think I can go in and change everything in one minute. I have the ability to surprise people who assume I can’t accomplish anything and to disappoint people who think I can fix everything.”

Howard asks all his radio show callers the same thing: “This is Clark Howard, how may I be of service?”

If he wants Atlantans to elect him as the next mayor, he’ll have to answer that question himself.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)