This story originally appeared in our February 2013 issue.

It was a bright weekday in mid-September and the Cormier boys—thirty-one years old, identical twins, best friends, incorrigible malcontents—were coming home. Their sixty-two-year-old father looked out his living room window as a U-Haul rumbled into the gravel drive. Bill Cormier did a double take. A U-Haul?

Bill had never known what to expect from his boys, William and Chris. Before they’d turned five, the brothers had burned down Bill’s house in New Orleans after taking turns playing with a cigarette lighter. William, older by five minutes, sounded the alarm: “One of the beds is on fire. And I didn’t do it!”

But if they had not been model sons, neither was Bill an exemplary father. After the fire, he had opened an escort service, the continuation of a career path that often put Bill on the shady side of the law. Even after he divorced his wife and won sole custody of the twins, the family was always on the move, Bill chasing a new job—hotel manager, computer technician, salesman. By the time William and Chris were sixteen, they’d gone to eighteen different schools and lived in eight states.

Raised in an atmosphere of impermanence, the two had come to rely on the one constant: each other. William was the dominant one, protecting Chris. As the boys grew into adulthood, so did their resentment against their father, resulting in the occasional fistfight.

But early in 2012, after more than a year on their own, the twins had come home—partly out of obligation to Bill, his disabled sister, and her two kids, and partly because of their own financial woes. In August the reunited family rented this simple one-story brick house in Winder, Georgia. Between Bill’s disability check and the twins’ poker winnings, the family seemed to get by—as long as tempers idled. It helped that William and Chris frequently left on gambling trips. But when they were all present, the six ate dinner in the dingy, drafty kitchen, and played Uno at the table. Bill was so happy to have the family reunited that he hung some old portraits on the living room wall—mop-topped toddlers wearing matching red soccer shirts and striped socks; teens in Navy Junior ROTC uniforms, smiling through braces. The boys teased their father for being sentimental, but that is how he always saw them—young, happy, together.

On that September day, Bill passed the portraits on his way to the driveway to greet his sons, who were just returning from a poker trip to Florida, William driving the truck, Chris following in the Chrysler they had driven down. Why the U-Haul? Bill wondered. He peered in the back of the truck and saw boxes of comics, an orange chair, some other furniture. But what struck him was the smell—a horrific odor coming from the back. It smelled like death.

Four hundred miles south, in the Florida Panhandle city of Pensacola, Patricia Burke was worried. She hadn’t been able to reach her friend Sean Dugas for weeks. This wasn’t like Sean, whom she’d known since he was three years old. Now thirty, bearded and dreadlocked, he’d earned a reputation as a free spirit who befriended everyone, from the retirees he met at the cigar shop to the teenagers he tutored through late-night Magic: The Gathering games at area comic shops. A reporter by profession, he was recognizable from his videos on Gulf Coast lifestyle—how to eat crawfish and make MoonPies—for the website of the Pensacola News Journal.

On August 27, Patricia and Sean had agreed to meet at the ranch house Sean owned on the city’s northeast side. But before Patricia could get to Sean’s front step, she saw a large man, his head shaved, leaving the house, closing the door behind him.

“Sean’s not here,” the man told her. Then he drove off.

Patricia left a note on the front door: Call me.

A week passed with no word. On September 7, Patricia returned to the house. She peered inside the front window. The place was empty. Gone from the walls were the charcoal etchings of the Eiffel Tower and Notre Dame. Gone was Sean’s vast collection of Magic cards. Gone were his bottles of craft beer. The only thing left was his bulky old-model big-screen TV. Sean could be flighty, even scatterbrained. And since he hung in so many circles, it was not uncommon for one group to lose track of him for a while. But Patricia knew one thing for sure: Sean would never move without telling anyone.

She inquired with the neighbors. They told her that days earlier, a U-Haul had been parked out front. They saw at least one man loading it. The stranger told a neighbor that Sean had been beaten up and was going to live with him. Worried, Patricia called Sean’s father, who reported Sean missing on September 13.

After that, all she could do was wait.

Back in Winder, the twins had a simple explanation for their father’s inquiries: The U-Haul’s contents belonged to their friend from Pensacola, who got out en route. And the smell? That was their friend’s dog, who’d been left in the brothers’ care, but who had died on the way. Then the two closed the rolling door, removing nothing, and went inside. The story seemed odd to Bill. Why would they have dropped him off without his furniture? But his sons didn’t seem upset. He was glad they were home.

A few days later, the boys said they were going to bury the dog in the backyard. The smell was so bad, Bill worried the neighbors would complain. He refused to go out back. Gradually the odor disappeared.

William and Chris unwound from their trip. With six people packed into the three-bedroom house, the brothers shared a queen-sized bed, separated by a pregnancy pillow. Chris began talking about applying at KFC; the manager was a friend. William was trying to convince his younger brother to join him as a professional poker player. For once, Bill stayed off their cases. Things were calm.

On the morning of October 8, Bill was awakened by a phone call from Pensacola police, asking after a missing man who had last been seen with William. Bill didn’t know any Sean Dugas . . . Wait. The dog. At first, he said nothing and hung up. Then he paused. His sick sister. Her kids. They all depended on him. They also depended on the twins, asleep in their room. He felt like vomiting. Bill had no choice. He called the investigator back.

William and Chris had gone shopping for lawn bags at Walmart when Bill led Winder police to the patch of recently disturbed earth later that day. When the twins returned, they spotted the cops and turned around. An officer followed and eventually pulled them over in their Chrysler Sebring near the city limits.

Meanwhile the house was under siege. Police. Helicopters. A track hoe. News cameras. Reporters. Bill was in the backyard, daring gawkers to judge. The hole in his yard deepened.

Beneath a freshly poured concrete slab, authorities extracted a blue storage bin about the size of a coffee table. Inside they found the intact and contorted remains of a decomposing man wrapped in a clear tarp. The cause of death was later determined to be blunt force trauma to the back of the head. Dental records would confirm the body was that of Sean Dugas.

The twins were charged with murder and concealing a death. Chris was held in the Barrow County Detention Center in Winder. William was incarcerated in neighboring Jackson County.

Police pressed each individually for details on how Sean Dugas ended up in their backyard. United, they could withstand anything. But now that they were apart, how long would it be before that bond began to crack?

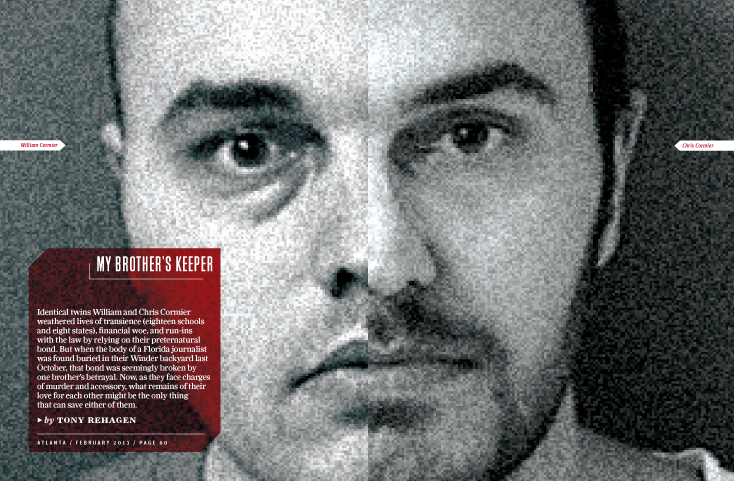

William and Christopher are two parts of one zygote that split inside the womb. It happens just three times out of every thousand pregnancies. Their facial features, their bone structure, their DNA are identical. Born with the same intestinal malformation, the boys would flash matching surgical scars just below their ribs as false proof to classmates that they had been conjoined. As with many twins, friends and family say, the two grew up in their own world. To this day, they often seem to share the same thoughts, to be two halves of one person. “It makes me jealous,” says their father. “They have such a strong bond.”

But there were stark differences from the beginning. William was born first; Christopher followed five minutes later, ten ounces smaller, bound for a weeklong hospital stay after William went home.

Eventually Chris caught up to William, and their mother dressed them alike. The pair became almost indistinguishable riding bikes or playing Super Mario Bros. Sometimes a teacher would take her eye off them for a moment, look back and call out for one of them before realizing the two had switched places.

The boys grew up hearing Bill’s tales of his own youth as a small-time criminal. Though they have no memory of the event, they became well aware that after they torched their parents’ house in the mid-1980s, their father started an escort service called A Touch of Class. In 1986, while William and Chris were living with their grandmother in Mississippi, their mother was arrested for prostitution. In an attempt to get the charges expunged, Bill arranged an undercover sting with local law enforcement and the DEA, using his business to ensnare miscreants—a scenario straight out of a 1970s B movie. Bill blamed the strain of those undercover days and the sordid arrest of his wife for the fights and, eventually, the divorce.

The twins survived by sticking together. In school they played pranks, switching classes, IDs, sometimes even girlfriends. For William, the good grades came easily, and he tried to help Chris, who had to work for B’s and C’s. Even back then, William’s demeanor was serious, Chris’s more carefree. When a schoolmate messed with Chris, he let it slide. Not William. By fifteen, William had already started to outweigh Chris by a few pounds and had sprouted an inch taller.

It was twenty years ago, in the comic book shops of Pensacola, another way station in a peripatetic childhood (their dad was selling cars in town), that William and Chris first met Sean Dugas. All three boys were obsessed with Magic: The Gathering, a fantasy game in the vein of Dungeons & Dragons, played with cards representing different creatures, weapons, or powers. By the time they were teenagers, Sean and the Cormier brothers had amassed thousands of cards, decks they would draw from in late-night and weekend tournaments.

Sean was a year younger than the twins, a “Breezer” from across Pensacola Bay in peninsular Gulf Breeze, a wealthy suburb. But contrary to the elitist Breezer reputation, Sean passed no judgment. Like the brothers, he was a child of divorce. William and Chris felt like they could talk to Sean about anything. For two people who rarely cultivated relationships outside their own, making friends with Sean was unusual. But in 1996, just as they prepared to start high school, their father found a job in Atlanta. The family was uprooted again.

Perhaps it was jealousy over the boys’ bond that led Bill to try to be their equal more than their father. When they got jobs at fifteen, Bill expected them to contribute to the household bills. When they dropped out of school midway through their sophomore year, he didn’t intervene. When he struck Chris in an argument and the two seventeen-year-olds ran away, he didn’t give chase.

But the boys could never escape—the same combination of dependency and obligation always brought the three back together. As they became adults, the twins adopted their father’s nomadic tendencies.

Oddly, Chris was first to break away, for a job running a Kansas Waffle House when he was nineteen. Left alone with the family dysfunction, twenty-year-old William joined the Navy and got married in 2001. But Bill soon moved his mother and the twins’ little brother to live with Chris, now the provider. In 2003 Chris was arrested for possession of meth with intent to distribute. From his station in Pensacola, William was furious at Bill for not keeping his younger twin out of trouble. He also blamed himself.

Without his twin, William was faring little better. He injured his back and was discharged from the service in late 2004. He got a $50,000-a-year corporate job with Waffle House in Georgia, and in 2006 he became a father. But a year later, his wife divorced him, he lost custody of his son, and he lost his job, finding himself stuck with more than $600 in monthly child support.

To weather these hardships, William and Chris gravitated to each other. William helped Chris get a job at a Waffle House franchise. Chris helped William with child support. The two began playing poker. The next five years were a blur of service jobs and moving in with and away from their father. In 2009 the boys were busted in Bill’s Dahlonega trailer with a safe full of marijuana. Chris took the fall—probation and a $1,000 fine. After a subsequent brawl between William and Bill, the twins lived in William’s Mercury for four summer months, parking overnight in quiet neighborhoods and the Walmart parking lot, the windows rolled up in the sweltering heat to keep out bugs while the brothers ate potted meat sandwiches.

In 2010 William got a job as a poker dealer at the greyhound racetrack in Pensacola. Chris became a regular at the tables. Scott Davidson, a fellow poker dealer, recalls their apartment: “It was like they would have the same thoughts. One would offer you a drink while the other was making it. It was like a well-oiled, 1950s-type home.” Matching shaving kits sat side-by-side in the bathroom. One twin cooked and the other washed dishes. Another frequent guest at the Cormiers’ Florida abode was a lanky, dreadlocked reporter who loved to smoke, drink beer, and talk the Cormiers up about anything. Through everything—all the years and all the moves—Sean Dugas was the one friend the twins had managed to hold on to.

At the end of last August, William and Chris left on one of their gambling trips, this time to the poker rooms in and around Pensacola. Sean had invited them to stay at his house while they were in town. When the two arrived at Sean’s on August 22, they found their host with his jaw wired shut, his trademark bushy beard shaved off. Sean had been knocked unconscious at a party days earlier. But he didn’t let that spoil the reunion. He hugged his guests. “He was excited to see them,” says Dherry Day Jr., Sean’s friend who was there at the time. Later the four headed down to the Spanish Trail Pub & Eatery, where over pitchers of beer, the twins joked about exacting revenge on Sean’s assailant. When Sean’s pain worsened, they offered to take him to the emergency room.

But during the following days, a rift between the Cormiers and Sean became apparent. Rhys Watkins, another of Sean’s friends, says that Sean spent four or five nights sleeping on Watkins’s couch across town. “He didn’t want to go home,” says Watkins. Sean didn’t seem afraid of the twins, just annoyed. After everyone had been getting along so well, suddenly it seemed the brothers had outlasted their welcome. “He didn’t want to be the asshole to tell them to leave,” says Watkins.

Nevertheless, on Monday, August 27, the Cormiers took Sean to his appointment with the oral surgeon. As they left, around 11 a.m., Sean used William’s phone to call Patricia Burke and set up lunch for that afternoon.

In a windowless room at the Barrow County jail, Chris Cormier sat across from two detectives from Pensacola. It was October 16, eight days after his arrest, and Chris hadn’t been sleeping. He hadn’t eaten in a week. His father worried he might try to kill himself.

This is what Chris told the detectives: On August 27, the same day as Sean’s lunch date, the twins and Sean were in the Pensacola house. Then Chris heard a man scream. It was Sean, being chased by William. The five-foot eleven-inch, 140-pound Sean ran into the garage, toward a back door, but the 220-pound William caught him just before he could open it. Chris saw his brother strike Sean in the back of the head, according to the eventual indictment, with some sort of instrument. Sean was dead.

William took charge. He drove to a nearby Walmart and bought a plastic tarp and a blue moving bin. He rolled the lanky body in the tarp and Chris helped him fold it into the box. Then they left the bin at the house—but not Sean’s Magic collection, which was later valued at between $25,000 and $100,000. It was William who sold cards to a man at a local comic shop for gas money back to Georgia; William who peddled cards to vendors at DragonCon in Atlanta that weekend for around $5,000, and a few more cards at a store in Newnan; William who sold the rare “Black Lotus” card—the most valuable Magic card ever released, worth into the tens of thousands of dollars—to a vendor in Tennessee.

And when the twins returned to Pensacola on September 3, it was William who hired a lawn service and cleaning crew to tidy up after he and Chris had loaded Sean’s remains and his possessions into the U-Haul. And once the cargo arrived back in Winder, it was William who buried the bin behind their father’s house.

In his report, Pensacola police detective Daniel Harnett concluded with one summative remark: “Christopher stated that William killed his friend, Sean Dugas, for his money, associated with the collection of Magic cards.”

The detectives returned to Pensacola. Chris was escorted to his cell, confused, agitated. What have I done?

Nine days after Chris’s statement to Pensacola police, William learned that he had been charged with first-degree murder and robbery with a weapon in Escambia County, Florida; Chris with accessory after the fact and, ultimately, unarmed burglarizing of an unoccupied dwelling.

In a letter to his father, sent from the Jackson County jail, William wrote, “There has been changes with my charges thanks to you know who (for the worse).”

William had nothing but time to think about it. Still, he couldn’t believe Chris would willingly betray him. He needed to talk to him, but as codefendants, they were forbidden to have contact with one another.

On November 16, William was prepared for extradition to Florida. Handcuffed and shackled, he didn’t know when or where they were taking Chris. He didn’t know if he would ever get a chance to confront him.

But to his surprise, after all the state of Georgia had done to keep these alleged coconspirators separated, the state of Florida saw fit to transport them together in the back of the same van for the 400-mile trip to Pensacola. (Escambia County authorities did not respond to inquiries as to why.) William was placed in the back of the van. Chris sat near the middle. They had not had any contact for forty days, and now they were feet apart, separated by a grate through which they could easily speak. Finally, after weeks of wondering how Chris could have sold him out, William could ask him directly.

“Are you trying to put a needle in my arm?” he demanded.

“No, no, no, no,” Chris insisted. “I would never testify against you.” And William should’ve known better, Chris said. He explained to William that the statement had been made under a state of food- and sleep-deprivation. He told William he was on suicide watch. (A representative of the jail denied that Chris was on any heightened surveillance.)

The response satisfied William. As the van pulled onto the open road, the tension subsided. Even if Chris had owned up to the statement, William was not about to waste this opportunity to talk to his closest friend. Who knew when or if it would ever happen again? After more than a month apart, spending hours worrying about each other, William’s anger and Chris’s guilt were easily swept aside. They were twins. Two halves of a whole. No one understood them like they understood each other. They spent five and a half hours just talking, not about the case, but about their individual incarcerations. Catching up. They stopped at McDonald’s. They savored each other’s company as the outside world flew past.

They arrived at the jail in Pensacola, where they were assigned to different cellblocks, Chris on the sixth floor and William on the second. They were finally living under the same roof again—four floors apart. As they parted, Chris said goodbye: “I love you, brother. I’ll see you when this gets over with.”

Both William and Chris are slated for trial on March 11. But it is unclear whether they will actually be tried together. Both have pleaded not guilty. As of late December, neither had met with their trial attorney.

Talking with the twins separately over the phone, I immediately started to sense a collective consciousness. Both claimed not to remember the first ten years of their lives. Both disavowed their mother. Both saw a connection between their transient upbringing by a self-proclaimed scofflaw and their current predicament—and yet both still wished their father would write them more often. Over several weeks, I heard both independently shift from sadness to anger over their father’s absence. They knew he’d tipped off authorities. They knew he felt guilty. But they told me they have things in the Winder house that can be sold. Right now, William says he can’t afford paper, much less a forty-five-cent stamp or an envelope.

The Cormier brothers spoke over the crackling long-distance lines in the same low monotone. William was reserved, careful in what he said. He grimly acknowledged that the odds are against him in this case. Chris was more prone to prattle, oddly confident that he and William could beat the charges. He desperately maintained his innocence, and insisted that the statement he made to the detectives wasn’t completely true, though he wouldn’t elaborate. He said that neither he nor William killed Sean, and he doesn’t know who did. Without going into detail, he said that he and William left the house and returned to find the body. Why didn’t they call the police? Why did they pack the body and the crime scene into a U-Haul and bring it 400 miles to Georgia? Chris didn’t address the specifics. All he said was, “I didn’t make that decision. That was Will.” Chris maintained that he did not load or drive or ride in the U-Haul, nor did he profit from anything in it. He said he intends to file a court motion to get his statement dismissed on grounds that he was mentally unfit to make it.

But the damage has likely been done. Despite his initial anger at his brother’s statement to police—which could mean the death penalty for William—William still feels responsible for his twin. After all, he’s spent a lifetime looking after his brother. “I would do anything I could to help my brother,” he told me. “Even at the expense of my own life.” But it seems that the only card William could play—confessing to charges he’s already pleaded not guilty to—would cost him his life, whether by execution or decades in prison. That may be the only way to free part of himself before the other half is condemned. For his part, Chris won’t think of living free while his brother languishes. “If he gets life in jail, I’m not entirely sure I could go on living,” Chris says. “That’s the end of the world for me.”

But the end of the twins’ world may have already come. They are separated, unable to help or encourage each other. Each alone, sleepwalking through the daily jail routine, all they have is time to think about and miss their other half, pacing the floor stories above or below. William has concocted hypothetical deals offering prosecutors information in exchange for having Chris moved to the same cellblock. But alone at lights-out, the fear creeps in—the thought that he might never see his twin again. “I think about him every night,” William says. “It’s impossible to get him out of my mind.”

Even in the prolonged Georgia autumn, the Winder house is cold. The oven door is open, its electric burner struggling to heat the entire kitchen. With the twins gone, the family is living on $1,300 per month in disability. Bill sold the Chrysler. Sold his laptop. There will be no Christmas.

Bill huddles at the table, choking down a nutrition shake at his niece’s insistence. He hasn’t been eating. His moods range from kicking chairs over in rage to waking up sobbing. When he’s calm, Bill still seems fond of relaying his outlaw past. Yet he is torn between having done the “right” thing—turning in his boys—and doing anything to protect them.

Bill bends over a stack of jail-inspected letters from the twins. There are envelopes and postcards from Barrow and Jackson counties—“Dear dad, You promised you would visit Saturday morning, what happened?”—and letters from Florida asking why he hasn’t written. He went to see them a couple of times while they were in Georgia, but the visits ended up in fights over money. Now that they’re so far away, he can’t afford the collect calls from jail or gas to travel back and forth to Florida. Bill is also afraid. Facing his boys in jail means facing his own failures as a father. “I’ve tried,” Bill says, voice breaking. “What am I supposed to say?”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)