It’s difficult to imagine that an idyllic green field in North Georgia, with a clear, burbling spring edged by cedars, was once the site of a makeshift Cherokee internment camp. But in 1838, 199 Cherokee were marched to this spot in Cedartown, just south of Rome, to await removal into Tennessee and, from there, Indian Territory in Oklahoma. These were the first steps of what is now known as the Trail of Tears, an 800-mile journey that marks the forced exodus of some 15,000 Cherokee from the Southeast, more than 4,000 of whom died along the way.

Until this past fall, Georgia’s removal sites were not included in the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which, as it was originally conceived in 1987, commemorated only the Cherokees’ passage west—not the places and events, such as the military seizures and internments, that led to their journey. But last spring, President Obama signed the Omnibus land bill, extending the boundaries of the trail into Georgia. It was the culmination of twenty years of work and the efforts of hundreds of people, including W. Jeff Bishop, president of the Georgia chapter of the Trail of Tears Association, and Tennessee U.S. Representative Zach Wamp, who worked with the state chapters to get the bill passed. “Nobody is doing this for money,” says Dr. Sarah H. Hill, historian and founding member of the Georgia chapter. “They are doing it as a way to recover our broken history.”

Until this past fall, Georgia’s removal sites were not included in the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which, as it was originally conceived in 1987, commemorated only the Cherokees’ passage west—not the places and events, such as the military seizures and internments, that led to their journey. But last spring, President Obama signed the Omnibus land bill, extending the boundaries of the trail into Georgia. It was the culmination of twenty years of work and the efforts of hundreds of people, including W. Jeff Bishop, president of the Georgia chapter of the Trail of Tears Association, and Tennessee U.S. Representative Zach Wamp, who worked with the state chapters to get the bill passed. “Nobody is doing this for money,” says Dr. Sarah H. Hill, historian and founding member of the Georgia chapter. “They are doing it as a way to recover our broken history.”

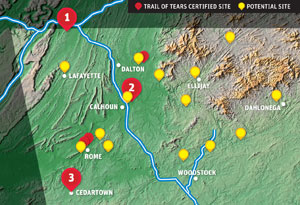

According to Hill, Georgia’s inclusion was crucial; it was one of the most aggressive states in removing its native people, and it had the largest population of Cherokee, around 9,000 according to a federal census conducted three years before the removal. Fourteen removal forts and camps—including Cedartown, which was the first Georgia internment site officially added to the Trail last fall—were constructed throughout North Georgia to house the evicted, who, according to the U.S. Army, numbered 4,000 at that time. (The remaining numbers are believed to have left Georgia before the removal.) The forts were often nothing more than campsites built in areas with large Cherokee populations.

And now? Bishop says the organization will continue to identify Trail sites and routes for approval, using oral histories, archaeological records, lawsuits, letters, and land deeds as evidence of a site’s history. Each site must also have little to no modern development; nothing should impede the visitor’s imagination of what the area would have looked like in 1838. (So Ellijay’s Fort Hetzel, for example—now an Ingles grocery store—may have some trouble.) Each approved site will then receive “wayside exhibits”—markers with pictures and text by Hill—explaining the property’s role in the removal.

“We are using these sites and using the power of place to tell this story in a very immediate way,” says Bishop. “It brings it alive and lets people know that the Trail of Tears wasn’t something that happened somewhere else. It happened in my front yard.”

Next page: A timeline of Georgia’s Cherokee removal

Cherokee Removal in Georgia: A Timeline

1802

Georgia cedes its western lands (now Alabama and Mississippi) in the Compact of 1802 to the federal government, which promises in exchange the eventual removal of all Native Americans from the state.

1831

In Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia, the Cherokee balk at the tight restrictions Georgia has placed upon them (e.g., not being allowed to meet, testify against a white man, or have a government). The Supreme Court rules that the Cherokee Nation is a “domestic dependent nation” outside the Court’s jurisdiction.

1825

The Cherokee capital is founded at New Echota, near present-day Calhoun.

1828

Gold is found on Cherokee land in Dahlonega.

1832

In Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court rules that the Cherokee Nation is a sovereign nation and as such is above any state law. Only the federal government has the authority to negotiate with another nation.

1835

Ousted Cherokee speaker Major Ridge signs the Treaty of New Echota, promising a Cherokee evacuation within two years. Many believe the treaty is invalid, as Chief John Ross (left) did not sign it.

1837

Construction begins on the first removal sites in Georgia.

1838

The roundup of the Cherokee begins in May; the last Cherokee are pushed out of Georgia by June.

This article originally appeared in the March 2010 issue of Atlanta magazine

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)