For our January 2021 issue, in honor of our 60th anniversary year, we dug through our archives to present a snapshot of the magazine during each of our six decades. We discovered groundbreaking work, inspiring stories, and, yes, some errors in judgement. Here’s what we found:

The ’90s in 5 Scenes

A dig through our archives unearthed a cinematic rendering of Georgia just before the turn of the millennium

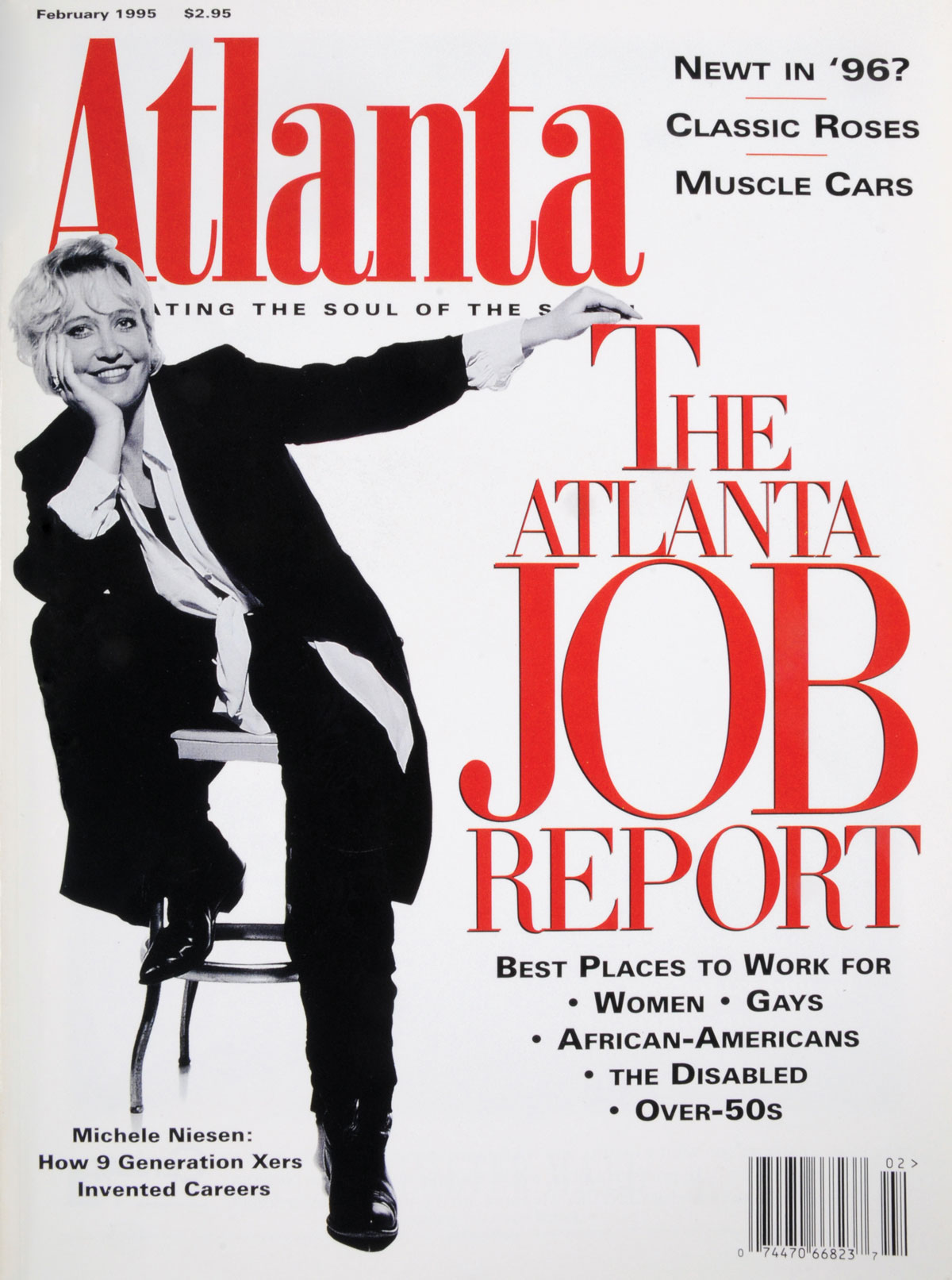

“The X-Files: Generation Xers aren’t so much breaking the old rules as making their own”

February 1995

Ten years ago, I had a list of what I wanted to be when I grew up: VP of Some Great Company, owner of a summer home, award-winning, brilliant copywriter, and maybe even married woman with husband in tow. . . .

A year ago, I found myself saying, “Would you like a lime with that?” and I wasn’t throwing a dinner party. Atlanta had a job for me alright, but I was wearing a uniform. I wasn’t VP of anything except the “Will I make rent this month?” club. . . .

Ah, to be in your 20s in the ’90s. I overheard someone say the other day, “Generation X makes me glad we’re nearing the end of the alphabet.” Walk a mile in my shoes, pal. Slackers. Misdirected. Misaligned. That’s what they say. Truthfully, we’ve been misinformed. . . .

Let go of the idea that you’re going to move to Atlanta and ease into some big fat job. It’s not going to happen. But that doesn’t mean you can’t make a living doing what you’re good at. You’re proactive or you perish in the ’90s Atlanta.

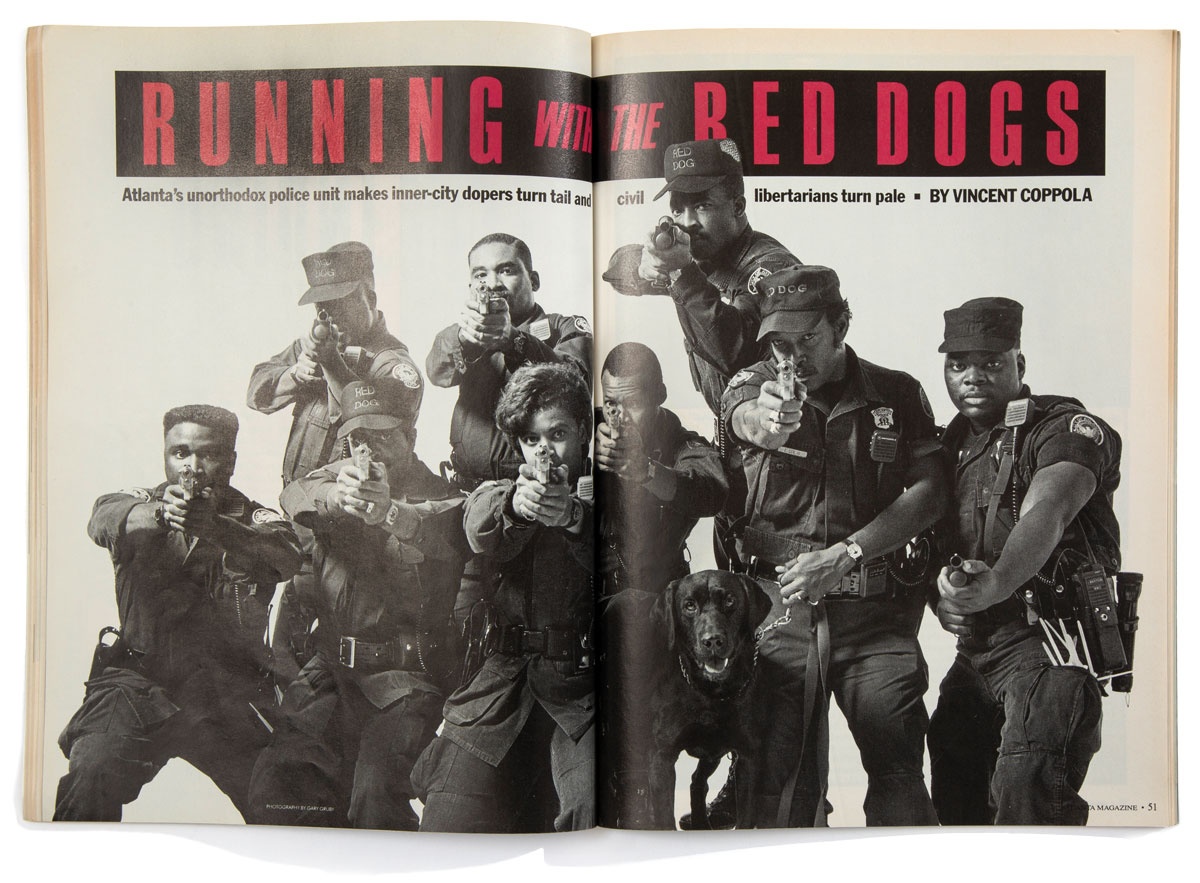

“Running With the Red Dogs”

“Running With the Red Dogs”

January 1990

Red Dogs wear black fatigues, heavy black nylon boots and black military-style web gear that runs over their shoulders like suspenders. Ammunition pouches, flashlights, a radio transmitter, steel and plastic handcuffs . . . and other accessories dangle from the webbing. . . .

Joe Little and Ken Allen are dressed for battle—some futuristic urban cataclysm out of The Terminator or Blade Runner. . . .

Their first stop is Hilltop Circle, a street winding around the Vine City housing project. As Allen and Little check garbage dumpsters, a favorite hiding place for drug dealers, a man in black jeans and a Miller High Life jacket darts out and races behind one of the apartment buildings. Moments later, he is sprawled face down in a patch of weeds. Allen, kneeling, holds the man in a wristlock while he pats him down for weapons. . . . .

The Red Dogs release the man with a warning to stay out of the housing project. . . . As we head back to the police car, a little boy who has been watching the encounter runs up cradling a toy Uzi machine gun. “I got a gun too,” he chortles.

—For this story, the writer spent three shifts riding with the APD’s then two-year-old (and already notorious) tactical unit. The story’s intro observes: “Red Dog tactics make civil libertarians queasy, but thus far, no complaints of brutality or mistreatment have been sustained.” More than two decades later, following the 2009 illegal raid at gay bar the Atlanta Eagle, the Red Dogs would be disbanded.

“AIDS: Small Town, Big Problem”

November 1990

On a bright summer’s evening in Albany, Ga., eight people are gathered at a plank table outside Picnic Pizza Numero Uno on Slappey Boulevard, bent over their lasagna and chicken parmigiana. Three of them—a sunburned, pickup truck–driving horticulturist named Randall, a 31-year-old unemployed Black man named Kenneth Ray Lee, and a bearded logger named David—are in various stages of AIDS infection that will likely kill them in the next few years. . . .

Randall, a gentle, sad-eyed man who describes himself as “living in Tifton, with a redneck accent, redneck ideas,” says he recently mustered enough courage to write an unsigned letter to the editor of the Tifton Gazette, asking for understanding for AIDS victims. (“Nobody wants to talk about it. Nobody wants to see it.”) Newspaper policy required that he submit his full name, even on an “unsigned” letter. He did—and the newspaper printed the letter—with Randall’s full name below it. “I panicked,” says the 6’8” Randall. “I thought I’d lose my job.” Thus far, the reaction has been mixed. His boss, a “pecan expert” at the University of Georgia, was sympathetic but puzzled. He’d assumed his towering “gimme cap”–wearing employee was straight. . . .

“I don’t like that term gay,” he adds. “This is not a happy lifestyle. I am what I am—a farm boy from rural Georgia. I’d like to think I’m not that different from anybody else.”

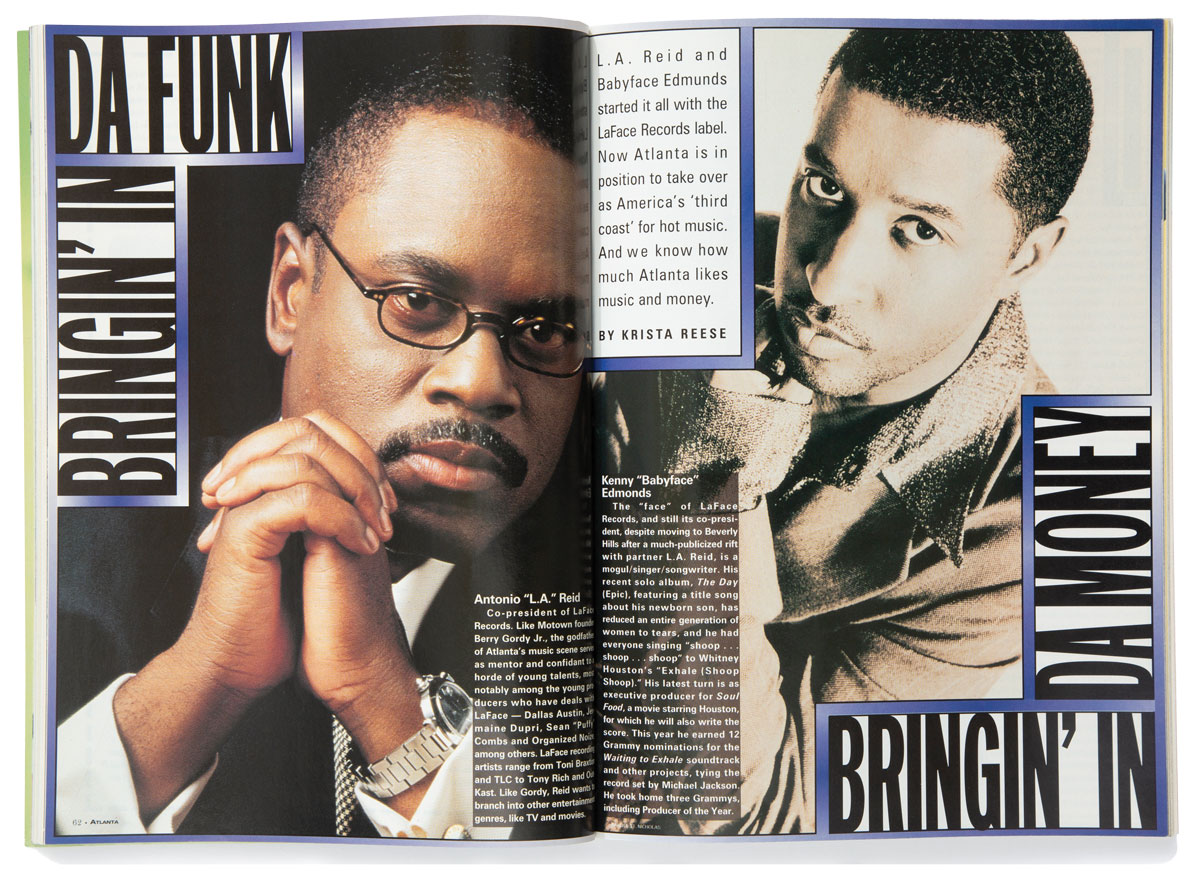

“Bringin’ in Da Funk, Bringin’ in Da Money”

“Bringin’ in Da Funk, Bringin’ in Da Money”

April 1997

It was just a little birthday party. Just a little soiree at the house, for 300 or so of Antonio Reid’s closest friends, . . . one of the most impressive bashes Atlanta has seen in years, a private gathering at a suburban mansion that revealed and typified both the style and reach of Atlanta’s thriving Black music scene.

Some of the best-known young African Americans in entertainment, from Queen Latifah to Toni Braxton . . . mingled with stylish, upwardly mobile partygoers who could have been dress extras for Waiting to Exhale. The fashion came from HollyHood, the Atlanta hip-hop clothing shop owned by Sandi “Pepa” Denton, of Salt-N-Pepa, and also leaned heavily to Versace, Donna Karan, Dolce & Gabbana.

Inside an enormous tent, a martini bar offered a menu of specialties: chefs sauteed scallops and veal to order; guests plucked strawberries from a life-sized “palm tree” made of fresh fruit. Vanilla-scented candles flickered on the tables. . . .

As a beaming Reid, in a white Versace suit, escorted fashion-plate solo artist Toni Braxton . . . through the crowd, the evening took on the air of a wedding thrown by a prosperous father eager to show how far the family had come. And in a way, that’s what it was. Reid put Atlanta on the R&B map when he and partner Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds started their label, LaFace, here in 1989. Since then the scene has exploded. . . . Earlier this year, as testament to the city’s strength as a music mecca, Black artists with local connections received a total of 22 Grammy nominations, taking home six. . . .

Atlanta entertainment lawyer Joel Katz conservatively estimates local music industry revenues (of all types, including concerts) at more than $500 million a year. The worth of LaFace alone is estimated at more than $250 million. “No CEO knows the money generated by these young guys,” said Mayor Bill Campbell, at a party for wunderkind producer Jermaine Dupri.

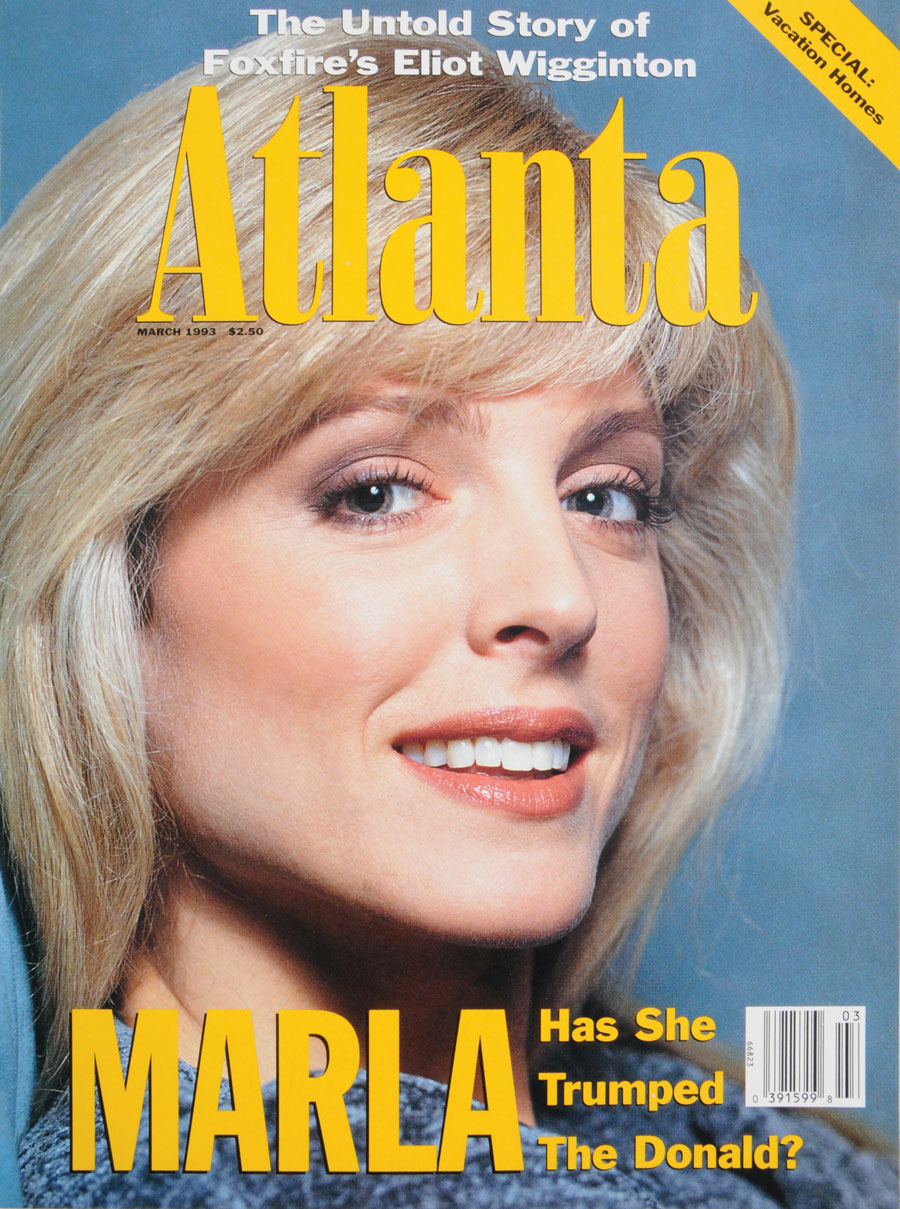

“Marla on the Mend”

“Marla on the Mend”

March 1993

Marla Maples sits at a corner table at the Ritz Carlton’s Jockey Club, across from Central Park. It is late afternoon. The elegant dining room is hushed, almost empty. Maples is stealing a private moment away from the jostling crowds, the endless gossip, the exhausting demands of The Will Rogers Follies, the Broadway musical she’s appeared in since last August. She’s struggling to adjust to a life without the tumult and extravagant madness of Donald Trump, trying, she hopes, to heal her wounds. . . .

Trump devoured Maples as surely as he swallowed Atlantic City and much of Manhattan. And, for too long and, seemingly, too little, Marla Maples let him do it, enjoyed his plunder. She was, after all, a 24-year-old from Dalton, Ga., wooed before envious millions by an elegant, airborne Croesus. Now, months after what may have been still another final breakup, Maples says she is trying to free herself, as Ivana did, from Trump’s tangled webs. It will not be easy. There are still volatile feelings between the two. At the beginning of the year, Trump, rebounding from years of financial woes, was reportedly pursuing Maples again. Rumors of marriage were swirling in New York on Super Bowl weekend. “I’m fighting to have my own soul,” insisted Maples, “to stay on my own path.”

“Presumed Guilty”

December 1996

On October 28, Richard Jewell made perhaps his last run through the media gauntlet when he walked with his lawyers into a roomful of reporters gathered at a hotel conference room in north Atlanta. “The public trial in the media of Richard Jewell is over, and the verdict is not guilty,” said Lin Wood, a lawyer who will handle the civil suits Jewell intends to file.

“We’re glad the emperor has finally admitted he has no clothes,” added Watson Bryant [an attorney and friend of Jewell]. When asked if he was disappointed the FBI had offered no apology, Bryant paused and smiled ruefully. “They don’t have the guts to apologize,” he responded. . . . “There was not one bit of evidence, and look at what they did to him. It’s unbelievable. This investigation was like a freight train; once it got started, it wouldn’t stop.”

Moments later, dressed in slacks and a cream-colored dress shirt with blue stripes, Jewell stood up and at last addressed the very same cameras that had stalked him for three months. “This is the first time I have ever asked you to turn the cameras on me,” he said. “You know my name, but you do not really know who I am. . . . For 88 days, I lived a nightmare. . . . I felt like a hunted animal followed constantly, waiting to be killed. . . . In their mad rush to fulfill their own personal agendas, the FBI and the media almost destroyed me and my mother. . . .”

Before he concluded, Richard Jewell put down his prepared statement. He paused for a moment and then looked directly at the cameras. His voice turned strong, as though it was resonating for the very first time.

“I am an innocent man,” he said.

This Old House

In the middle of Buckhead’s glitz, Bacchanalia serves great low-tech food in a quaint Tudor cottage

By Christiane Lauterbach | August 1993

Twenty-eight years ago, our restaurant critic (who’s our critic today!) reviewed a charming little restaurant that stood in stark contrast to the dining scene’s bombastic glam. She wisely concluded—be sure to read to the end—that this restaurant would have significant staying power. It also would redefine the nature of fine-dining in Atlanta and beyond and, later, shift the center of culinary gravity away from Buckhead to Atlanta’s Westside. Read the review

Obsession

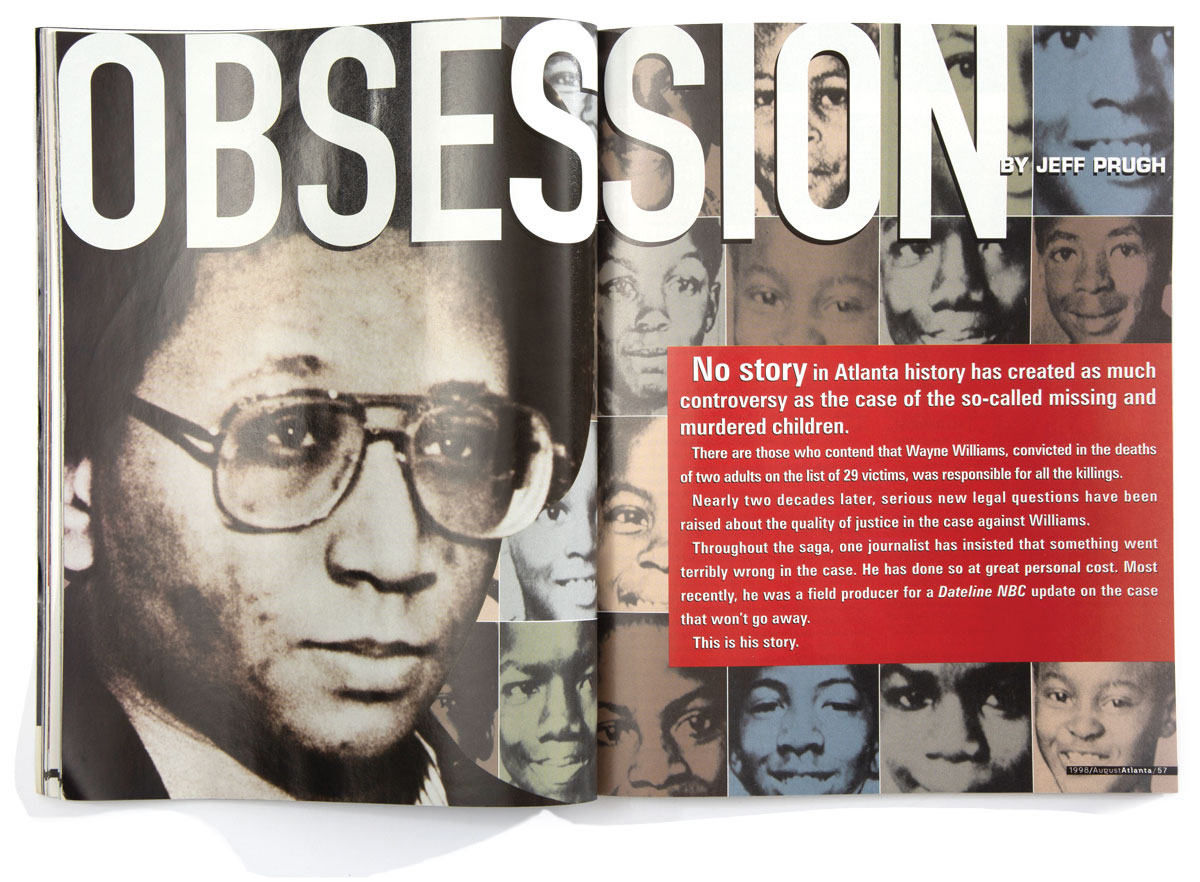

No story in Atlanta history has created as much controversy as the case of the so-called missing murdered children.

By Jeff Prugh | Originally published August 1998 and excerpted here:

By Jeff Prugh | Originally published August 1998 and excerpted here:

Editor’s note: Speculation about the guilt of Wayne Williams has not waned in the 23 years since Atlanta published this story by a journalist who’d been convinced early on that the case against Williams was flawed. In 2019, after a recent hit podcast and HBO docuseries about the Atlanta Child Murders, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announced that police would attempt to retest evidence tied to some of the killings attributed to Williams—but for which he was never prosecuted.

There are those who contend that Wayne Williams, convicted in the deaths of two adults on the list of 29 victims, was responsible for all the killings. Nearly two decades later, serious new legal questions have been raised about the quality of justice in the case against Williams. Throughout the saga, one journalist has insisted something went terribly wrong in the case. This is his story.

I remember first the headlines, which began stacking up on my desk while I was away on assignment, yet which resound to this day like screams in the night. I remember, too, the photos of the kids—with names like Yusuf and Jeffery, Angel and Cristopher, LaTonya and Clifford—whose eerie disappearances and deaths seemed to cry out for attention I was too busy to give. Too busy shuttling between Miami and Key West, writing for the Los Angeles Times about the Liberty City riots and the Cuban boat lift and their aftershocks. . . . None of us could have imagined back then that metro Atlanta and the “city too busy to hate” would soon become traumatized by some of the worst crimes of this century, if not the South’s most agonizing murder cases since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. . . .

Here is a saga that would consume me and bushwhack my career in newspapering, yet more significantly put heat on Atlanta’s police, our judicial system, our news media, while shedding extraordinary light on how they too often fail us—more than a decade before the police and the media reminded us of their fallibility in the case of Atlanta’s own Richard Jewell, the target of a media firestorm as a suspect who was later cleared in the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in 1996. Here I was—a transplant from California, a refugee from the sports beat—pounding the streets when I wasn’t pounding a typewriter, seeking answers from authorities, but getting mostly illogic and sham. . . . Here I was, brimming with enough cynicism to fill the Omni, burning enough bridges to make General Sherman look like a piker, my journalism career in flames when the Times moved its Atlanta bureau to Miami and I chose to stay in Atlanta to pursue this story that to me is bigger than any individual, any career, any newspaper, any jury’s verdict. . . .

I forged friendships with two guys who had happened to be grilled by police as murder suspects within five weeks of each other during the spring of 1981. The first, an iconoclastic ex-cop named Chet Dettlinger (now an attorney), who investigated the cases on his own after police rejected his and three erstwhile colleagues’ offer to help. He had already asked me to help him start work on The List (a book on the cases, published locally in 1984) when authorities called him in, ludicrously, and asked him questions Chet said they couldn’t answer. The second: Wayne Williams, once a freelance TV cameraman and would-be Berry Gordy–esque pop-music promoter, still the only person convicted in any of those 29 killings that made up metro Atlanta’s “missing and murdered” cases between mid-1979 and mid-1981. Today, at 40, Wayne Williams has waged an interminable appeal for habeas corpus relief and freedom from consecutive life sentences. . . .

Consider that the state ambushed Williams and his trial attorneys, in their opinion, by persuading the judge to allow into evidence 10 so-called “pattern” victims, meaning he had to defend himself, in effect, against 12 murders, not two, and that exculpatory statements to authorities point to stronger suspects than Williams—suspects the police and FBI knew about, but the jury did not. . . . As Williams said in prison, where he corresponded with at least one victim’s mother and enlisted my help while he writes what he hopes will be his autobiography, “More than anything else, I want the truth to come out.” I couldn’t hope to find the truth in the herd instincts of the media, which, for the most part, marched in lockstep with the authorities, wolfing down handouts without bothering to examine what they were being fed. . . . To my amazement, I would find much of the truth suppressed by police for years in a four-inch-thick file on 12-year-old Clifford Jones. . . . Of the 29 murder cases that authorities assigned to their so-called official list of victims, Clifford’s cries out loudest. . . .

Six months after Clifford Jones’s killing, I received a tip that the investigation was in shambles. I decided to call Chet Dettlinger to compare notes. As Atlanta overdosed on headlines that screamed ANOTHER BODY FOUND, and TV newscasts began, “It’s 11 o’clock, and there’s a curfew. . . . Do you know where your children are?” we met over breakfast at a Howard Johnson’s coffee shop in Sandy Springs. . . . Unfurling his map across the table, [he] position[ed] salt and pepper shakers to symbolize victims, matching them with numbers on squiggly lines that represented major streets. . . . In a lower corner of Chet’s map, I noticed a list of unfamiliar names. “Who are these people?” I asked. “They’re murdered people, too.” “Children?” “Children and adults.” Now, their names, too, fell on me like a ton of bricks. Now, I sensed that Atlanta’s nightmare was worse than what our public officials were telling us. “But what about the task force list?” I asked. “Screw the list!” he said. “It’s arbitrary. It has no parameters. Nobody knows how big our problem is. Nobody knows when it began, and we may never know if it ends. . . .”

My research shows that the murders of young Atlanta Blacks did not stop when Wayne Williams went to jail 17 summers ago. These kinds of murders that authorities attributed to Williams or assigned to their list of 29 never stop. The truth is, the police stopped counting—and the press stopped reporting. Nothing, however, symbolized the missteps, the mix-ups, the misinformation more than “the list.” By putting some victims on it—and leaving many others off—almost on a whim, without valid parameters, then Public Safety Commissioner Lee P. Brown, now mayor of Houston, created a monster. Brown’s office would not respond to Atlanta magazine’s repeated calls for comment. If Brown didn’t assign a victim’s case to the list—its victims Black, eventually ranging in age from 7 to 28, all but six of them juveniles, all but two of them males—that victim became nonexistent to most of the media and the masses. The list, then, blocked down from view not only dozens more killings of children and young adults but the excruciating reality that, for all those terrifying headlines and crime scenes on the 11 o’clock news, Atlanta’s problem was much worse. . . .

October 1981: As Wayne Williams awaits his trial, my home telephone rings late at night with a call from Chet, who had accepted an invitation to join the defense team. “Jeff,” he says, “I’m looking at part of a police file on Clifford Jones’s case. It turns out they had an eyewitness—and a much stronger suspect—in Clifford’s case than they’ve got in the two cases that Wayne will be tried for.” “What a story!” I blurt out. And what an introduction to the other suspect, Jamie Brooks, a 29-year-old Black man who managed the coin laundry at the Hollywood Plaza shopping strip. . . . There, Clifford Jones’s body had been found, wrapped in plastic, beside a Dumpster during the predawn of August 21, 1980. There, too, Jamie Brooks denied having anything to do with Clifford’s death, but showed “indications of emotional disturbances” when answering “no” to incriminating questions on a polygraph test. On November 1, a 19-year-old witness named Freddie Cosby is interviewed by a GBI agent identified in documents as R. Simmons. Excerpts:

Simmons: Freddie, when they took the little boy in the back room, what did they do to him?

Cosby: They got him in the butt. They made him lay on the bed. Jamie and Calvin [Smith] got him in the butt. . . .

Simmons: Freddie, when they were getting the little boy in the butt, was he crying or saying anything?

Cosby: Yes, he was crying and saying that he wanted to go home; he was hollering real loud.

Simmons: Freddie, what did they do to the little boy when he started crying real loud?

Cosby: . . . Jamie put a rope around the little boy’s neck and pulled on the rope.

Simmons: . . . Freddie, did Calvin or Jamie say, ‘The little boy’s dead’?

Cosby: They both said it. Jamie and Calvin both said that the little boy was dead.

Police would make no arrests in this case. Ultimately, police would close Clifford’s case, attributing his death to Wayne Williams, based on “fiber evidence,” even though Williams’ name appears nowhere in the investigative file. Jamie Brooks died in 1987 of complications from AIDS. The whereabouts of Calvin Smith are unknown. . . .

In 1986 . . . I would swear out an affidavit in support of a citizen’s complaint stating that Clifford Jones’s investigative file had been unlawfully withheld in defiance of the Georgia Open Records Act. Within days after the file had been released by court order, then WSB-TV reporter Bob Sirkin interviewed veteran homicide detective Sidney Dorsey ([later] DeKalb County sheriff), who had worked Clifford’s case and others for the Atlanta police. On camera, Dorsey says Jamie Brooks—not Wayne Williams—is the best suspect in the Jones case.

Sirkin: It is your belief—is it not?—that James Edward Brooks killed Clifford Jones.

Dorsey: I haven’t seen anything that has changed my mind as yet.

Sirkin: What would you like to see done with this case? What should be done with it?

Dorsey: I’d like to see it reopened.

Just like that, Dorsey was demoted. WSB-TV took Sirkin off the story after he had rolled out more stories based on the newly released files—the station was pressured, he says, by the offices of the Fulton County district attorney and Atlanta’s public safety commissioner. . . .

One of the very few Black voices to raise hell remains that of Camille Bell, who long ago marched on City Hall with some victims’ parents, demanding action after her nine-year-old son, Yusuf, was found slain in November 1979. She recently sat down for the NBC telecast I worked on. “I’m truly ashamed of the Black people involved—the Black mayor, the Black police chief, the Black judge,” said Bell, who now lives in New England and whose son’s death also is officially attributed to Williams. “Sometimes power, position, greed, wanting somebody, is more important than poor people. This is the first time I’ve ever witnessed Black people doing it to Black people.” . . .

Nobody, in my opinion, got justice. . . . Not Eunice and Emmanuel Jones, Clifford’s mother and brother. Not Camille Bell and the other parents of victims whose cases are attributed to Wayne Williams or remain open. Not Wayne Williams, his father, Homer, now 84, or his mother, Faye, now deceased. Not Chet Dettlinger, his teaching job in the University of Georgia system abolished in 1981 after he was questioned as a suspect, one month before Wayne Williams would be stopped near the bridge. Not the people of metro Atlanta, whose leaders and institutions they trusted must be held accountable for the kinds of betrayals that nobody deserves. Not I. Could any of us really let go of all this? Could any of us really walk away—after one year, after 10 years, after 17 years, after eternity?

A Plague of Politics

By Vincent Coppola | May 1994

By Vincent Coppola | May 1994

The Centers for Disease Control has been reinvented. Once, it was home to a vigorous little band of independent-minded researchers who expanded the agency from a World War II malaria control operation into a potent strike force designed to track down and eradicate infectious disease anywhere on earth. But that was before CDC itself came under the microscope of politics, before it had a billion-dollar budget, before politicians and engineers decided to redefine what constitutes infectious disease, before social agendas were given more attention than social diseases. Read the article

Five years after we published “A Plague of Politics,” we ran another feature story about the CDC—this one focused on the likelihood of a pandemic reaching America. Here is a brief excerpt from that 1999 story.

“At War With an Invisible Army”

April 1999

C.J. Peters has a vision of how the human race will be wiped out. What he sees in his visions—in his nightmares—are viruses, the kind you read about in the tabloids and the New York Times, the kind that drive the plots of movie thrillers and fill nightly newscasts. Peters, head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Special Pathogens branch, has spent three decades hunting down viruses in remote corners of the world. . . .

Peters’ vision is driven by decades of experience and education at the frontlines of high-tech battles against microscopic killers, but his fears reflect our own. Baby boomers grew up fearing nuclear holocaust; today’s generation faces a new terror—bugs, not bombs. Kids today don’t face air raid drills, but they wash with antibacterial soap and learn about the risks of dirty needles and contaminated saliva as early as first grade. . . .

Peters says the unleashing of a pandemic could come not so much from deliberate terrorism, but eventual evolution, the right factors of an equation line up. . . .

Peters, however, is not a despairing man. . . . Unimagined medical breakthroughs have kept us furlongs ahead in the race for survival. But there is a lesson here: . . . We too must keep pulling the lever, struggling to evolve not just beyond the microbes, but beyond our own destructive nature. In that, says Peters, there is hope.

“We’re not going to cure death, but the effort we put into fighting it off, and the reverence we place on the value of every human life, says more about us as a species than anything else I can think of.”

This article appears in our January 2021 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)