Five years ago, Doreen Eitel left Germany and ended up in Columbus, Ohio, where she worked as an au pair. She married and moved to Tampa. Two years ago, the couple moved to Atlanta, and Eitel was pleasantly surprised.

“I have discovered things that make Germany feel a little closer, and Atlanta feel more like home,” says Eitel, 28, who works for Novem, a German-owned business in Austell that provides car interior parts to companies like Mercedes-Benz, which in January announced it would move its U.S. headquarters from New Jersey to Atlanta. Mercedes joins upwards of 250 other German-owned firms—think Siemens and Porsche—with Atlanta outposts.

Mercedes will hire locals to fill some of the 900 or so jobs. Other workers will be relocated from New Jersey and Germany. This last bunch probably will be less interested in the generous tax credits that lured the company here than in knowing that they can still catch the FC Bayern München and Borussia Dortmund soccer game while downing mugs of Bitburger and devouring Leberkäse sandwiches, just like they would back home.

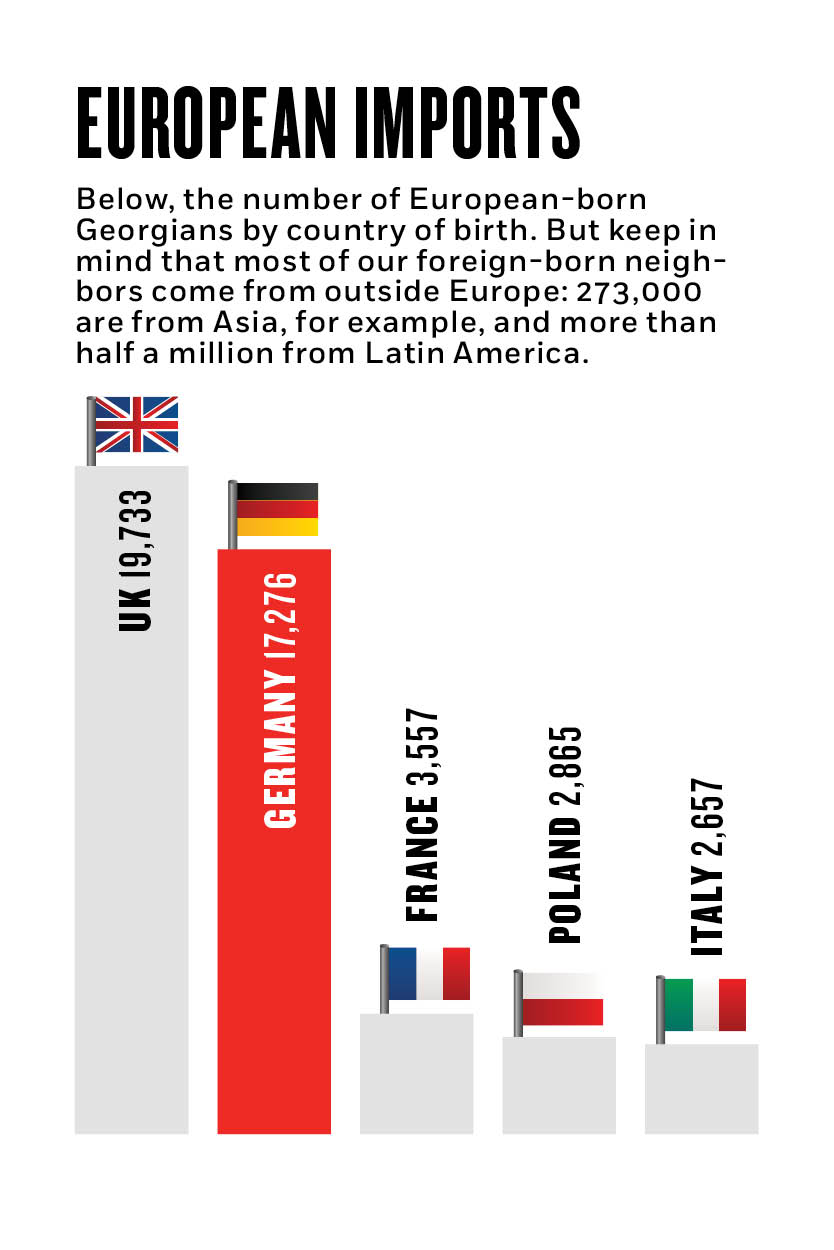

They’ll also find a 17,000-strong community of German expats here, who watch German soccer teams on a big screen every Saturday, August through May, at the Goethe-Zentrum Atlanta in Colony Square. They drink real German beer and eat ersatz German cuisine at Der Biergarten downtown. They get German sausage at Patak Meats and German bread at Bernhard’s Bread Bakery. They commemorate German reunification at Kennesaw State University, where a 12-foot-tall chunk of the Berlin Wall is on display. They get together at different German Meetup groups and they worship at German Church Atlanta.

Of course, German expats use the Internet to find all of this stuff, a luxury that Eike Jordan didn’t have when he moved here to establish the German American Chamber of Commerce of the Southern United States in 1978, “when the fastest way to communicate was to spend a fortune on a phone call or use the old Telex machine, which I did every morning when my brother sent me the latest soccer scores from Germany,” Jordan says. “Now I can just watch the games live on my phone.”

Back then there were 32 German-owned companies in Georgia and a growing interest in doing business in a region where the costs were low and markets were growing.

“The Consulate General at the time suggested the German Chamber organization open an office here,” Jordan says. “I’d never been to the U.S., but my wife and I always wanted to go across borders and have some adventure.”

He started the German School of Atlanta in 1983, partly because he wanted his kids to retain some of their German identity, but especially for German families living here on a temporary work assignment. “There was concern about keeping the German language, because for young children here, most of the day happens in English,” he says. “Those children had to go back to Germany and continue with their education. They couldn’t afford a language gap.”

These days it’s actually easier to find a German language class than it is to find a good bratwurst in Atlanta. The Goethe-Zentrum Atlanta has taught language classes for years and hosts events like the March 6 “Spieleabend” (German immersion game night) to encourage participants to speak German. Also, 170 public schools in Georgia offer German classes, including one—Ashford Park Elementary in Brookhaven—that offers a dual-immersion curriculum in which students spend half the school day learning subjects like math and science in German.

Jordan believes all of this German language education is the foundation of Atlanta’s German cultural existence (actually, Georgia is named for a German; King George II of Great Britain was born and raised in Germany). And he also believes that incoming Germans, with Mercedes or otherwise, won’t need an official welcome Volkswagen.

“They’ll have Southern hospitality, like my family had when we moved here,” he says. “We felt welcomed from the start. In New York, no one cares if you move there. Atlanta? People invite you into their homes, and they mean it.”

Cultural Exchange

For decades Germany’s government funded the Goethe-Instituts around the world, promoting German language and culture. Then, in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down, “and the money started going toward Eastern European and Asian countries,” Eike Jordan says. “They were closing Goethe institutes everywhere.” German businesses and the German American chamber stepped up. So did Claus Halle, a senior exec with Coca-Cola, who had established the Halle Foundation in 1986. The foundation has written checks to support German American cultural initiatives and student exchanges.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)