The Great Speckled Bird was born in controversy. The front page of its first issue, in March 1968, featured an illustration of then-publisher of the Atlanta Constitution Ralph McGill, alongside Lyndon B. Johnson and Jesus, emerging from a cracked egg. The accompanying feature was a harsh critique of his advocacy for the Vietnam War. While many decried the new publication, the emerging counterculture crowd—made up of college-aged activists, hippies, and habitués of Atlanta’s nightlife—clamored for more, and The Bird was happy to deliver.

Arriving on the heels of the civil rights movement, in an era defined by cultural upheaval, the Bird was a rallying point for the South’s leftist youth. The idea for the paper came in December 1967 when two Emory University graduate students, Tom and Stephanie Coffin, met with other students from local colleges to start a leftist newsletter. The Coffins, who had already distributed materials criticizing the Vietnam War on Emory’s campus, were aiming for a wider audience.

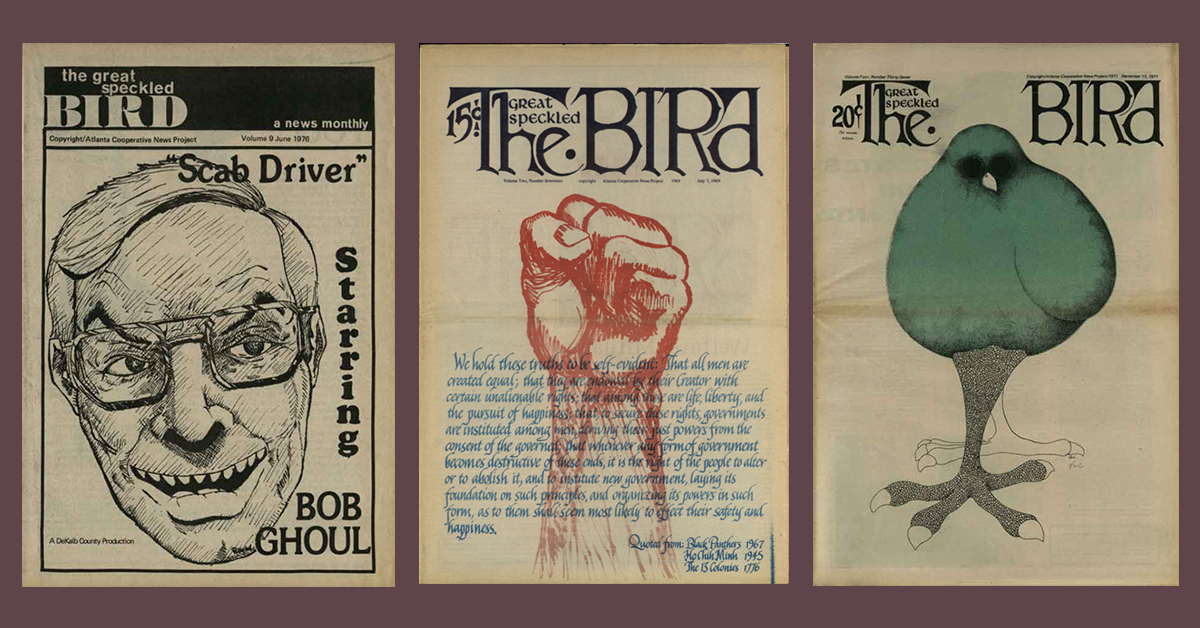

The Great Speckled Bird—named for a country-gospel song its staff members heard while creating that incendiary first issue—proved to be popular: Within six months, publication increased from biweekly to weekly. Volunteers sold copies on street corners and at high schools and colleges—15 cents for papers purchased in Atlanta, and 20 cents everywhere else. Subscriptions were also available and proved a valuable source of revenue. At its height, the Bird had a circulation of 23,000 that spanned the Southeast. Some staff were paid, but they only made between $40 and $60 a week and often took up other jobs to supplement their income. For them, the cause was more important than the money. Its organization reflected its progressive politics; content—politics, concerts, films, art, and theater—was determined by popular vote.

The staff faced resistance. Distributors, identified by their bohemian dress, were harassed by authorities and arrested on charges ranging from jaywalking to distributing pornography. Then, in May 1972, the house the Bird staff used as their office was firebombed in the middle of the night. The culprit remains unknown.

The Bird plodded on despite it all, publicizing protests and rallies and serving as an essential avenue of communication among activists and organizers. The paper spotlighted Angela Davis and Huey Newton, members of the Communist and Black Panther parties respectively, and drew national attention for its radical stories, which included coverage of hospital workers striking in Virginia and a piece on the destruction wrought by urban renewal policies on a low-income neighborhood in Atlanta. In 1971, Mike Wallace of CBS’s 60 Minutes called it “the Wall Street Journal of the underground press.”

But things began to change in the early 1970s when Midtown—a hotspot for Atlanta’s counterculture scene and the neighborhood the Bird operated out of—saw its creative crowd depart for other parts of the city, leaving the paper with few vendors and a much smaller readership. Two other alternative publications—the Atlanta Gazette and Creative Loafing—also came about during this time and proved to be formidable competition. Eventually, ad revenue dried up, readership declined, and internal squabbles erupted. It published its final issue in October 1976.

The Bird’s revolutionary message spoke to a generation hungry for change. Just as modern youth organizers have used social media as a catalyst for change, the Great Speckled Bird built a leftist network that allowed the political demands of Atlanta’s youth to take flight.

How are today’s youth taking political action? Read our story from this month’s issue: “Georgia’s Gen Z voters prepare to step up to the ballot box.”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)