Photograph by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

Penny liked to pick locks, and she knew where the snacks were kept. She’d sneak her friends into the food stores for late-night feasts—no simple trick for a 6,000-pound Asian elephant. “Heavy chains were found to be the only answer and were used to keep Penny’s sensitive trunk ‘finger’ from opening locked doors,” the Atlanta Constitution remembered in its 1971 obituary for the longtime Atlanta zoo resident.

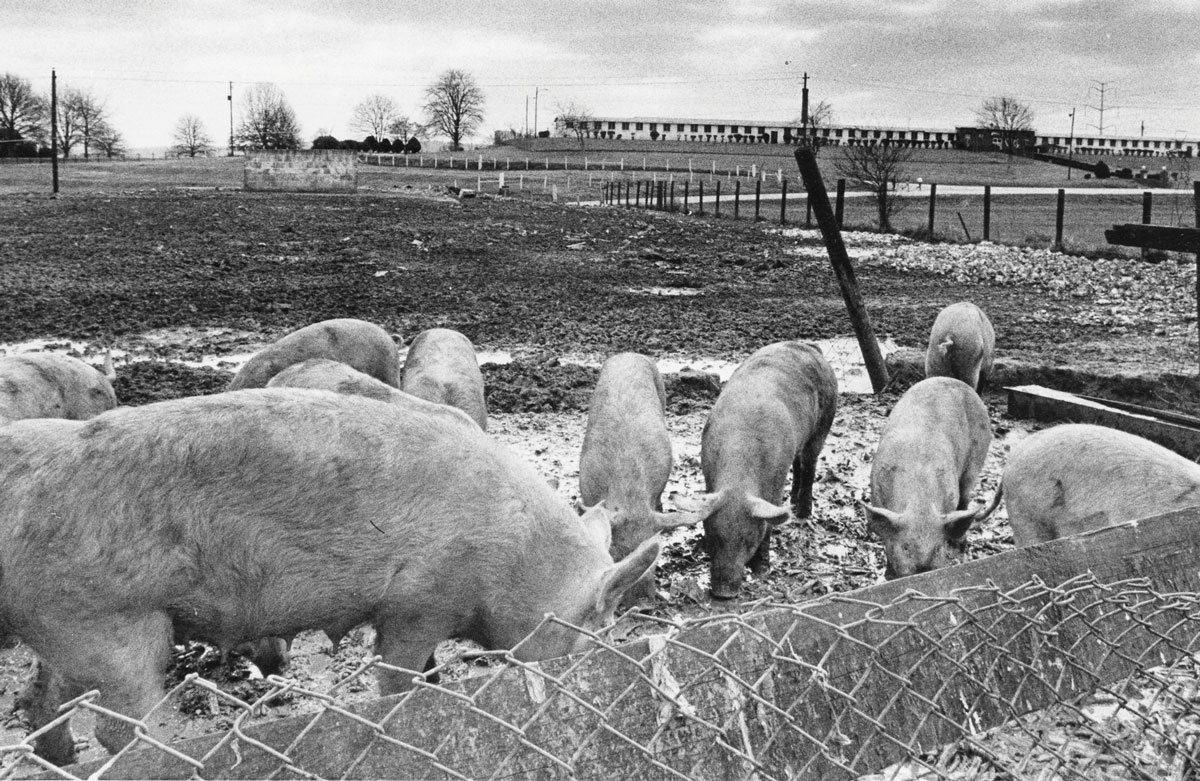

When Penny died, her remains joined those of other animals—a gorilla and other elephants, possibly a rhinoceros and a giraffe—at a makeshift graveyard in DeKalb County, on the site of what was then a city-run prison farm. In the 20th century, people detained there grew crops (vegetables “from okra to collard greens,” the newspaper said in 1976) and raised livestock to feed themselves and others incarcerated at local facilities, in addition to digging and maintaining the animals’ graves.

The prison farm closed in the 1990s, and, in 2009, a fire torched the roof of the compound’s main structure along Key Road—which has remained in disrepair, grown over with forest and kudzu. In recent years, the property has been of interest mainly to hikers, graffiti artists, and various other trespassers. Atlanta police also use part of it for target practice—currently the only legal use of the property. But more action could be on the horizon. In early September, the Atlanta City Council approved a proposal to construct a training facility for police and firefighters on 85 acres of the 300-plus-acre property known now as the Old Atlanta Prison Farm. (The remainder will be preserved as greenspace, including a public park.) The $90 million development, built and largely financed by the Atlanta Police Foundation, will be a place where officers can shoot guns, detonate explosives, and practice other tactics, and where firefighters can rehearse rushing into burning structures to extinguish flames.

Supporters of the plan, including Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, say current training facilities are dilapidated, officer morale is down, and the Prison Farm—located inside the Perimeter in unincorporated DeKalb but owned by the City of Atlanta—is the only feasible site on which the center can be built. But a broad coalition has opposed the project, which activists nicknamed “Cop City.” In a time of heightened scrutiny of policing, many people object to the construction of the pricey new facility—the city would chip in about $30 million—as well as the possible environmental impacts, like flooding or degraded air quality, in surrounding, mostly Black and brown neighborhoods. Opponents also point out that there were already plans in place for the land in question: It was previously envisioned as part of Atlanta’s next premier greenspace, the South River Forest—an expansive 3,500-acre tract proposed in the 2017 Atlanta City Design, coauthored by Ryan Gravel for the Atlanta City Planning Department. That plan had the forest, which contains the headwaters of the South River, linking the Old Atlanta Prison Farm with nearby properties including Constitution Lakes, Lake Charlotte, and Intrenchment Creek Park.

The animal remains have spurred conversation among the Atlanta Police Foundation, Zoo Atlanta, and the Atlanta Preservation Center. “The opportunity to understand what this space means—and will become—is the focus of many groups,” says David Mitchell, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center. The exact coordinates of the gravesites remain something of a mystery, although former visitors to the site recall seeing monuments at its northernmost edge, about a mile northeast of where the APF plans to build the training center, on property that would become parkland. (The APF declined to comment on the hypotheticals of what might be unearthed.) In any event, project leaders will be encouraged to protect the animals’ gravesites in the event they’re found on the 85 acres, Mitchell says, and environmental analyses should prevent bones from being mistakenly exhumed. “It’s just an unusual site that has a little pocket of Atlanta Americana in there,” says Rachel Davis, a spokesperson for Zoo Atlanta. “We want to honor the animals who are out there.”

It’s not just Penny: There are also the elephants Maude, whom prisoners buried in an 18-foot-long grave, and Coca, given to the zoo by Asa G. Candler Jr., son of the soda mogul; and a lowland gorilla named Willie B. Named for Atlanta Mayor William Berry Hartsfield, Willie B. “was distinguished as the only ape to run for Congress,” according to the Atlanta Constitution. He earned 663 votes in 1960 as a write-in candidate in the Fifth District—to the displeasure of the otherwise unopposed winner of the contest, Representative James C. Davis. (He’s not that Willie B., though; after the original perished in 1961, the zoo gave another new acquisition the same name. By the time he died in 2000, the second Willie B. had risen to become the city’s unofficial mascot, eulogized by Mayor Andrew Young. His cremated ashes are kept at Zoo Atlanta, whose protocols for interring the remains of deceased animals have evolved since the 20th century—along with just about every other aspect of animal care.)

And the bygone zoo animals aren’t the only memory this swath of land holds. There are the crumbled remnants of Atlanta’s circa 1902 Carnegie Library, the city’s first public library, which were trucked from downtown after the building was leveled in 1977, as well as rubble from downtown’s original Equitable Building, erected in 1892 and demolished in 1971.

Photograph by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

More darkly, there is the history of the imprisoned people who looked after the animals’ remains, who’d often been picked up for public drunkenness or other low-level offenses. Newspaper accounts as late as the 1980s compared the work undertaken by people incarcerated at the farm to “slave labor,” borne disproportionately by Black prisoners; activists have called for more research into possible abuses at the city facility. In the 1980s it was the subject of an ACLU lawsuit alleging “illegal and unconstitutional” forms of punishment—including the use of leg irons and extended periods of solitary confinement—and unsanitary conditions. (The city settled the suit in 1985.)

The training center isn’t yet a done deal: The next mayor could cancel the project, and opponents are continuing attempts to stall it. And before the land can be built on, it’ll have to undergo an environmental analysis that will involve, among other things, getting a clearer idea of what’s already there—and figuring out what to do with it.

This article appears in our November 2021 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)