Djamel Ramoul

Before Miami was a spot on the map, Tampa’s Ybor City was rolling Cuban cigars and baking bread the way las abuelas did in Havana. The humble ethnic neighborhood has quietly turned out a number of notable figures over the last century, from political activists to mafia bosses to baseball stars (ever heard of Al Lopez?). But with Cuba eyeing the area for its first American consulate in five decades and Ben Affleck’s Live by Night projecting the neighborhood onto the silver screen, Ybor is quiet no more.

Wallace Reyes tosses handfuls of crushed corn to the chickens in Ybor City’s Centennial Park. The morning light is lemon yellow, the air crisper than usual for this historic Tampa neighborhood. “I’m feeding my friends,” he says as colorful fowl emerge from the bushes. “They’re actually descendants of chickens who arrived here 131 years ago.” So they’re more than anachronistic—barnyard animals in a bustling Sun Belt city—they’re venerable, dating back to the birth of Ybor.

“Here comes Colonel Sanders,” Reyes says as a white rooster struts toward his breakfast.

Djamel Ramoul

Reyes is a fourth-generation Ybor resident and historian who makes his living selling cigars and giving walking tours; since I’m here to write about the neighborhood, he’s offered to show me around. He leads me across the street to where his Ford Model A is parked. “It’s in the movie,” he says, referring to the Ben Affleck adaptation of Dennis Lehane’s novel Live by Night, much of which is set in Ybor’s underworld of the 1920s and thirties. Last night, I watched a special screening of the movie at the Tampa Theatre; when the train carrying the main character, Joe Coughlin (played by Affleck), pulled into a station marked “Ybor City,” the audience went wild.

Djamel Ramoul

Reyes and I walk to the Ybor City Museum, once Ferlita Bakery, and he tells me Ybor’s story: In 1885, a Spaniard named Vicente Martínez Ybor came to town; a year later, he opened his eponymous cigar factory. He had already enjoyed success manufacturing cigars in Havana and Key West, and he set his sights on Tampa because of its port and the relatively new Henry Plant railroad.

Over the next four decades, Ybor became a cigar boomtown. Redbrick factories dotted the skyline, some topped with towers or cupolas so workers could spot ships carrying Cuban tobacco as they sailed into port. The area’s cigar industry ultimately outproduced Havana; by 1929, the pinnacle, Ybor was known as the “Cigar Capital of the World.”

Inside the museum, Reyes and I pause in front of an exhibit showcasing two cigar rollers’ tables; above them rises a recreated lector’s podium. During Ybor’s cigar-manufacturing heyday, workers sat for hours rolling tobacco leaves into tight flutes. To keep them from nodding off, lectores would read to them: newspapers in the morning, novels in the afternoon (Don Quixote was most popular).

Djamel Ramoul

Ybor’s booming economy and plentiful jobs attracted not just Spaniards and Cubans, but also Italians and Germans. The neighborhood became a successful immigrant enclave separate from, and more dynamic than, Tampa—the city into which it was annexed in 1887.

Each ethnic group built its own social club, or clubs, where people gathered to talk about the day’s events and receive medical checkups. As we walk through the museum, Reyes stops in front of an exhibit containing black-and-white photographs of the ornate club buildings. El Centro Español was for transplants from Spain’s Galicia province, while the Centro Asturiano served those from neighboring Asturias. L’Unione Italiana catered to the area’s Italians, most of them from Sicily. The Cubans, Reyes tells me, had a club for whites and a club for blacks.

As separate as they seemed socially, Ybor residents of all stripes came together at restaurants such as the Columbia to eat something representing them all: the Cuban sandwich. Each component of this lunchtime staple represents one of Ybor’s ethnic communities: The roast pork is Cuban, the ham Spanish, the salami Italian (this is the ingredient that sets it apart from the sandwich’s Miami version), and the pickle and mustard are German. A slice of Swiss cheese serves as the lone, if welcome, interloper. They’re all placed between two crusty pieces of fresh Cuban bread, made Tampa style with a palmetto leaf baked on top to help the bread expand. As the story goes, the Cuban sandwich was invented to replace the heavy midday meals that made cigar rollers sleepy; it had the anticipated effect, but its enduring popularity is something no one could have predicted.

Ybor continued to attract new immigrants until the Great Depression, which sent the cigar market downward and marked the beginning of the neighborhood’s decline. The Cuban Revolution, and the subsequent embargo, quickened its demise. (Yet another difference between Miami and Ybor: The upheaval that made the former crippled the latter.) Around the same time, a so-called urban renewal project leveled seventy acres in Ybor. But the “renewal” part stalled, and without investors or strong political representation, Ybor was left with blocks of empty lots.

Djamel Ramoul

In 1974, residents successfully lobbied for the creation of the Ybor City Historic District, which protected its nine remaining cigar-factory buildings and other historical architecture. In the 1980s, artists in search of inexpensive places to live and work began moving in. The neighborhood’s recovery was slow and a bit messy—wild nightlife spots opened in the 1990s, spurring crime and causing concern among locals—but today, Ybor is once again a bustling neighborhood where stores are open and people of all backgrounds mix.

This much is evident as I join a large literary pub crawl snaking its way along Ybor’s brick streets into lived-in coffeehouses and craft-happy bars. Sipping a sour raspberry ale at Cigar City Cider & Mead, I listen to a reporter from La Gaceta, Ybor’s newspaper, read one of his columns. And it occurs to me: These writers reading their works before an appreciative audience are the lectores of the twenty-first century. Ybor City has come full circle.

It’s lunchtime at the Cafe at the Columbia Restaurant. Across the table from me sits Andrea Gonzmart Williams, a fifth-generation member of the Gonzmart family that has owned the Columbia since it opened in 1905. A waiter in a black tie constructs the restaurant’s signature salad at our table, tossing iceberg lettuce, baked ham, olives, tomato, and Swiss and Romano cheeses in garlic dressing. (Like the Cuban sandwich, the salad’s ingredients nod to the area’s original immigrants.)

The tables around us are filled with patrons, and that’s something Williams doesn’t take for granted. After all, it was only twenty or so years ago that daytime business was so slow, her family boarded up the cafe windows and temporarily made it a nightlife spot.

Djamel Ramoul

According to Williams, her restaurant’s rebirth has coincided with Ybor’s. And when she looks outside and sees what’s happening, she’s hopeful about the future. “There’s art and culture,” she says, “restaurants and wine bars. Ybor is going in an awesome direction.”

Starting this year, it will have an added attraction: the Tampa Baseball Museum. Housed in the former home of Al Lopez—the city’s first player to make the Major League—the museum will tell the story of baseball in Tampa, past and present. While some exhibits will focus on the long line of baseball stars the city has produced (including Ybor’s own Tony La Russa, Luis Gonzalez, and Lou Piniella), others will take a wide-angle look at the town’s long-running passion for the game. For example, few people realize that before the Chicago Cubs moved their spring training site to Tampa in 1913, intersocial leagues were the talk of the town. Every Sunday afternoon, hundreds would gather at local ball fields to eat deviled crabs and watch the Sicilians take on the Cubans. Even in sweltering temperatures, immigrants stood outside for hours wearing their Sunday best, yelling for their home country as it competed in the signature sport of their adopted one.

Djamel Ramoul

The offices of La Gaceta occupy a former dry cleaners on a lonely stretch of Seventh Avenue. The country’s only trilingual newspaper, it is published in Spanish and English, with a column in Italian. Nine thousand subscribers receive it each week, most of them Hispanics living in Ybor’s 33605 zip code. Patrick Manteiga, editor and publisher, sits at his desk in a stingy-brim fedora and suspenders. Behind him hangs a portrait of his grandfather, Victoriano Manteiga, who arrived from Cuba in 1913 and worked as a lector before founding the Spanish-language paper in 1922. (It was Victoriano’s son, Roland—Patrick’s father—who introduced English into its pages.) The colorful portrait was painted by Ybor native Ferdie Pacheco, the famous “fight doctor” for Muhammad Ali.

Patrick tells me La Gaceta began advocating for an end to the trade embargo against Cuba in 2000; it was one of the first Spanish-language papers in the country to do so. The attitude of many here toward Cuba, I’m finding, is quite different than it is in Miami. Which is understandable: The Cuban-Americans in this area are not, for the most part, children of people who fled the Castro regime. They are fourth- and fifth-generation sons and daughters, and they see the prospect of renewed trade with Cuba as an economic opportunity. After all, they have a strong Cuban culture without fierce anti-Castro sentiment.

Giving me a tour of the offices, Patrick stops at a wall crammed with framed photographs of his father, or him, posing with politicians, celebrities, and dignitaries. Fidel appears in each of them. “The guy won,” Manteiga says, staring at the pictures as if for the first time. “He died peacefully in his bed.”

Djamel Ramoul

Rose Barbie grew up in Ybor in the 1950s. Her Italian father owned a grocery store; her Cuban mother was a beautician. She remembers everything: How a delivery man from La Primera (the forerunner of Ybor’s popular La Segunda Central Bakery) would arrive each morning before dawn to hang a loaf of fresh Cuban bread on a nail next to her front door; how she and her father used to see the doctor at L’Unione Italiana for a small monthly fee (“a precursor to HMOs,” she says); and how everyone in town, regardless of their ancestry, attended the Sunday tea dances at Centro Español.

After a teaching career and a decade spent working at the Ybor City Visitor Information Center, she now creates posters and greeting cards using old cigar labels. Her daughter Monica makes purses from cigar boxes. “I keep my lipstick, keys, phone in here,” Monica tells me, opening a beautiful Gurkha cigar box on a chain strap.

Rose and I stroll down Seventh Avenue, planted with towering, L.A.–like palms and belted by black wrought iron balconies. I note the absence of steeples. Churches—the heavyweight hubs of most well-established ethnic neighborhoods in America—maintain a low profile here.

We arrive at King Corona, a cigar shop and cafe. Smokers and drinkers fill the front patio; inside, owner Don Barco gives Rose a big hug. “This was downtown when I was a kid,” he tells me. “Not downtown Tampa. This is the heart and soul of the city.”

His store sells around seventy-five kinds of cigars, mainly from Nicaragua, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic. “Cuban tobacco is the most overrated thing on the planet,” Barco says. “When the growers and processors left Cuba after the revolution, they took the seeds with them.”

Djamel Ramoul

Two blocks east, Mike Cincunegui and his mother, Sandra, also make a living selling cigars. Their shop, Long Ash Cigars, rolls more than forty varieties on-site, luring curious passersby who want to see the work up close. “A cigar is more than a product,” Mike says. “It is the culture, the history of Ybor.” Like Rose and Barco, he understands that visitors want to take home a piece of that history, and he has turned the fortunes of the past into a profitable venture for the present.

Djamel Ramoul

I am at the Tampa Bay History Center, a dazzling downtown museum rising by Garrison Channel, walking the grounds with its representative Emanuel Leto. I ask about the small number of churches in Ybor. “It was a factory town founded by an industrialist as a place to make money,” he says. What’s more, a number of immigrants, though they came from Catholic countries, were anticlerical. For many years, Leto notes, L’Unione Italiana held its meetings on Sunday mornings—something that would have been unthinkable back in Sicily. Ybor harbored a strong anarchist movement.

And, as Live by Night shows, it was a hub for organized crime as well. I return from the museum to Ybor, where I meet up with Scott Deitche, who gives mob-themed walking tours of the neighborhood. He takes me to the northwest corner of Seventh Avenue and Fifteenth Street. “This used to be Las Novedades,” he says. “It was a popular eating spot for the wise guys.”

Ybor’s port facilitated smuggling—everything from drugs to illegal immigrants. Rackets were run out of the buildings and goons were gunned down in the streets. The sawed-off shotgun, according to Deitche, was the weapon of choice. Names like Wall and Antinori and Trafficante entered local, sometimes national, lore. Trials were held in the nearby federal courthouse, which has since been transformed into an elegant hotel, Le Meridien. (You can ask for one of the jail-cell rooms.)

Djamel Ramoul

It all makes for a tantalizing tale of underworld activity in Cigar City, and Deitche relays it with engaging aplomb. Take it from bestselling author Dennis Lehane, who gave him a shoutout in the acknowledgments of Live by Night, thanking him for the personal mob tour of Ybor.

Djamel Ramoul

I am back with Wallace Reyes, and we are standing on Cuban soil. Jose Martí Park is only .14 of an acre; it’s in the heart of Ybor City, but it belongs to Cuba. In 1956, Tampa gifted this land to what was then the Republic of Cuba in honor of Jose Martí, the great nineteenth-century Cuban poet and freedom fighter. Martí made frequent trips to Tampa in the late 1800s to raise money for Cuban independence from Spain, and he often stayed at a boardinghouse once located on this site.

During one visit in 1893, Martí delivered an impassioned speech to more than 10,000 cigar workers on the steps of Vicente Martínez Ybor’s cigar factory. With shouts of “Cuba libre!” the crowd vowed to fund or fight in the revolution. Newspapers around the country published photos of the scene; some say it was the moment that sparked the Cuban War of Independence.

Today, Jose Martí Park is quiet. A statue of its namesake hero watches over the small green space. Six mounds of dirt contain soil from Cuba’s six regions; they are the only plots of independent Cuban soil in the world.

Reyes looks at me. “Now,” he says with a grin, “you’re in Cuba.” And indeed I am. I can smell the espresso and cigar smoke in the air; from somewhere nearby, I hear a rooster crow. Ybor City, despite its ups and downs, remains the country’s original Little Havana, and it has its own slice of Cuba to prove it.

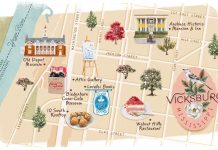

Things To Do in Ybor City

See Jose Marti Park

Stand on Cuban soil at this small park dedicated to the Cuban poet and revolutionary. Given to the people of Cuba in 1956, it is located on the site of a former boardinghouse that welcomed Marti during his frequent visits to the area. Download the Jose Marti Trail app to discover more Ybor City sites associated with Marti and the Cuban Revolution. josemartitrail.org

Tampa Baseball Museum at the Al Lopez House

Delve into Tampa’s longtime love of the game at this Ybor City museum opening later this year. Original artifacts and interactive displays will tell the story of local baseball culture, including tales of the town’s popular cigar factory teams. tampabaseballmuseum.org

Tampa History Center

See one of the world’s largest collections of cigar memorabilia at this downtown museum. The Cigar City exhibition also describes Tampa’s cigar-manufacturing industry and the experiences of immigrants who settled in Ybor City. tampabayhistorycenter.org

Ybor City Museum

Learn about the founding of Ybor City at this museum housed in the former Ferlita Bakery. You may also tour a restored casita, or small house, that would have been home to a cigar factory worker and his family a century ago. ybormuseum.org

Eat Columbia Restaurant

Plan on lunch or dinner at this Ybor institution, the oldest restaurant in Florida. Order a pitcher of sangria made tableside, an original Cuban sandwich or deviled-crab croquette, and white-chocolate bread pudding. columbiarestaurant.com

La Segunda Central Bakery

Stop in at this century-old bakery for a flaky guava-and-cheese turnover and a cup of cafe con leche made with locally roasted and ground Naviera coffee. Be sure to pick up a loaf of Cuban bread featuring the signature palmetto leaf. lasegundabakery.com

Smoke King Corona Cigars

Enjoy premium cigars from around the world along with a pint of Peroni or a cup of Cuban espresso. Pick up a copy of La Gaceta and snag a sidewalk table for excellent people watching. kingcoronacigars.com

Long Ash Cigars

Watch master rollers at work and select locally made cigars from the walk-in humidor. Admire the tobacco leaf–covered bar as you sip coffee and shop for Rose and Monica Barbie’s tobacco-themed posters and purses. thelongashcigars.com

Stay le Meridien Tampa

Check in at this boutique hotel a couple of miles from Ybor City. A former federal courthouse that saw many a trial of Ybor City’s mobsters, the hotel preserves the architectural features of the 1905 Beaux Arts building. It also repurposes historical items such as the witness stand (now the restaurant’s hostess station) and offers guest rooms situated in former judges’ chambers and holding cells. lemeridientampa.com

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-218x150.jpg)

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)