In 1991 I was a ponytailed 28-year-old reporter, newly arrived on the Atlanta City Hall beat for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, at a time when city council was rife with corruption and a low fever of general incompetence. One day I watched the chairman of a powerful committee walk to the public lectern during discussion of a request on one of his own real estate projects, and begin arguing for approval to himself. Not surprisingly, he won his own support.

The council wasn’t just ethically challenged; it also couldn’t shoot straight, blundering from one numskull vote to another. In 1994, revving up for the world’s approaching arrival at the 1996 Olympics, the council voted to invite Bucharest, Hungary, to become a sister city. Oops. Bucharest is in Romania.

Let’s be clear: This was an equal-opportunity circus. White, black, male, female, gay, straight—every constituency had one or more dubious riders on this runaway train. Fortunately for Atlanta, there were still a few bright spots. The city’s first black mayor, Maynard H. Jackson, had just been returned to office after an eight-year absence, and he was doing his best to keep the locomotive from flying off the tracks. A few city council members also seemed flabbergasted by it all. Most notable of them was a little-known young lawyer—a janitor’s son from Raleigh, North Carolina, who’d worked briefly in the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice before being elected. He was earnestly pushing (though getting nowhere) for the city’s first comprehensive code of ethics.

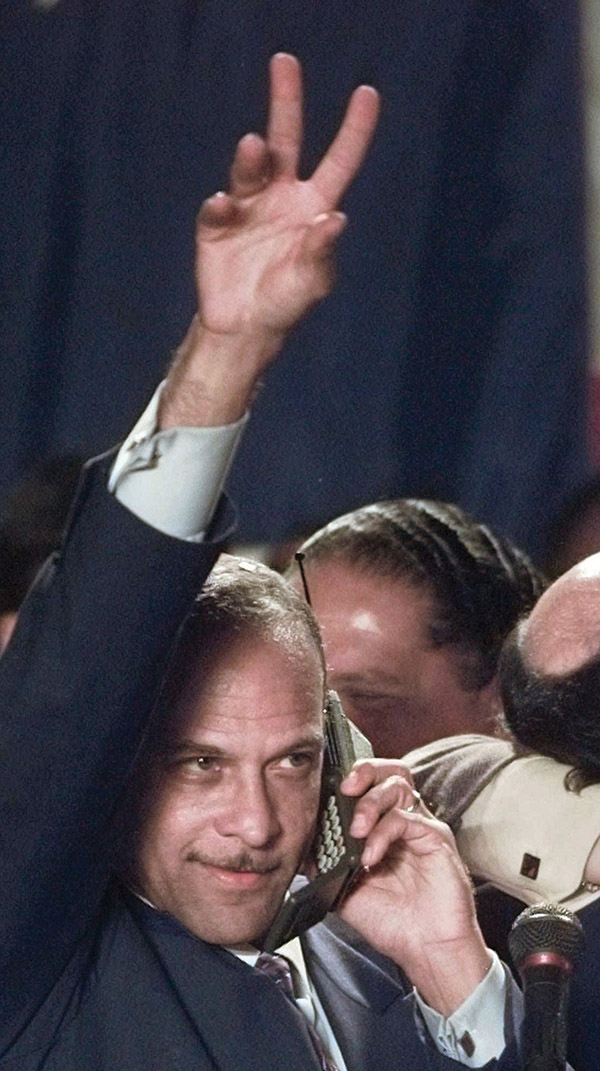

His name was Bill Campbell.

Over the next five years, I made my journalistic career shooting fish in a barrel of dirty politics—with Campbell, elected mayor in 1993 and then reelected in 1997, at times quietly encouraging me.

It turned out that some companies with leases to operate restaurants, stores, and vending machines at the airport had been paying off city politicians for years: with bundles of money; with expensive jewelry; and even, in the case of longtime councilman Ira Jackson, chair of the committee that oversaw the airport, an ownership percentage in the airport’s biggest chain of gift shops. Later he maneuvered into being named the city’s aviation commissioner, all the while clandestinely receiving “profits” of more than $1 million as the shops expanded under his blind regulatory watch. It wasn’t just the airport. Officials in charge of managing the city’s pension fund accounts were flagrantly lining their pockets at the expense of Atlanta retirees.

Meanwhile the city was crumbling: During a raging thunderstorm in 1993, after years of warnings and never-funded plans to address them, a decrepit sewer line under a hotel parking lot near Georgia Tech collapsed into a 50-foot-deep sinkhole—sucking two hotel workers into the earth with it. They drowned in a raging torrent of mud; one body, packed with silt, was found near a sewer system outlet two miles downstream.

By the end of 1994, six people, including Ira Jackson, one of the first black politicians to win any office in Atlanta, and D.L. “Buddy” Fowlkes, a white councilman and legendary former head track coach at Georgia Tech who was beloved by Buckhead voters, were on their way to federal prison in connection with the payoffs. Undercover video by the FBI also surfaced capturing one of the corrupt businessmen, Harold Echols, slipping $500 into the coat pocket of then–city council president Marvin Arrington. (Arrington, later appointed to a Fulton Superior Court judgeship by Governor Roy Barnes, was never indicted. Arrington said the money was for tickets to his annual birthday party, and presented documentation he had deposited the money into a campaign account.)

I was under fairly explicit orders from the AJC’s editors to prove that Maynard Jackson (no relation to Ira) was a crook. It was an article of faith among many at 72 Marietta Street—the newspaper’s old headquarters—that Jackson must be guilty of something, though it was never clear exactly what. Many in white Atlanta’s business community had never gotten over Mayor Jackson’s then-“radical” demands after first being elected in 1973, such as that Atlanta banks add some black and female professionals to their boards if they wanted to hold city accounts. Accepting the conventional wisdom, I did my best to nail him, running down claims and curious threads everywhere in the gorgeous neo-Gothic corridors of City Hall. The threads never led to Jackson, though. He made mistakes—especially by appointing some people who abused his trust. But personally he was as clean as politicians come. When the big corruption cases began surfacing, he let the cards fall—even when people he had once had great faith in were clearly going to be crushed. He was a sterling individual.

And then there was Campbell.

He had always been a bit caustic and often unbearably arrogant. Even as a councilman, he would erupt over perceived slights. Early in the 1993 mayoral race, he called me in a rage over a brief in the AJC. It didn’t mention him by name but said fundraising was off to a slow start for the two announced candidates and noted that his opponent had been to Washington, D.C., to raise money. “It’s outrageous and reprehensible,” he bellowed—upset at a nonexistent implication that the other candidate was doing better than him. After the call, I said to a colleague, “If I wrote that guy was Jesus resurrected, he would complain I didn’t say he was God.”

But Campbell was also smart, driven, and, it seemed, ethically clean. When I reported in the AJC during the 1993 mayoral race that Echols, the bribe-happy airport businessman, had also claimed to the FBI that he’d paid Campbell, I dug through years of airport contract votes. Over and over again, Campbell had opposed the interests of companies involved in payoffs. It didn’t make sense that he was part of that conspiracy.

Campbell won the election and became mayor in 1994. He was a good one—at least initially. During his first term, his cabinet was eclectic, racially diverse, and, for the most part, highly effective. The city’s bloated 1970s-era finance department was overhauled and professionalized. Campbell passed a major bond issue to pay for infrastructure improvements leading up to the 1996 Olympics. Rebuilding began on Atlanta’s catastrophically failed public housing system. The city’s legal, public works, and water departments were retooled. It was a serious effort to modernize the core operations of city government—and one from which Campbell’s successor, Mayor Shirley Franklin, benefited in ways that went largely unacknowledged after Campbell’s downfall.

Most striking was what happened with crime. Atlanta’s rates had soared throughout the 1980s and early 1990s—a seemingly intractable barrier to reviving intown neighborhoods. Campbell campaigned on a promise of community policing and huge numbers of new officers. (He fell short on the hiring goals.) No one can prove exactly what causes these things to change, but violent crime rates reversed and continued falling throughout his tenure.

I began to wonder if he might be “the one.” Even with all the prickliness, he seemed to be about the business of making things work. He could charm little old white ladies and business owners on the Northside when he wanted to. Could he be the post–civil rights movement black politician who would leverage the economic rebirth of Atlanta, build a bridge to white voters, and become a U.S. senator or a Georgia governor? Or more? I wouldn’t hear of a Harvard graduate named Barack for another decade, but what I was really thinking in the mid–1990s was: This guy might be Obama. And Atlanta felt like the place where that figure could—and should—rise.

Everyone has demons, of course. Campbell’s looked modest back then. There were poker games with a select group of buddies at his house that didn’t sound like a good idea. You could see he appreciated smart, beautiful women, but who doesn’t? In public he was a ramrod: no alcohol, beaming smiles, perfect in every picture.

Then there was Freaknik, the black student street party that swelled into a massive, raucous event in the mid-1990s. It brought gridlock, mayhem, and lewd displays for some city residents—and a very good time for a lot of others.

Initially Campbell and his police leadership worked with students to clean up the event. That wasn’t successful, so he bowed to pressure from white Atlantans and business leaders to crack down, arresting huge numbers of young people. That tamed things a bit, but Campbell got no credit from white Atlanta. I still remember the managing editor of the AJC at the time fulminating about Campbell in the newsroom, enraged that a reveler had urinated on the editor’s Midtown lawn. It didn’t register, or matter, to him the political risks Campbell had taken. After all, the mass arrests of young African Americans enraged much of black Atlanta. I could see by then Campbell had a craving for public affirmation well beyond most politicians. The renunciations left him writhing.

It made me think of a story Campbell told early in his career, about jumping into a pool as a little boy in his segregated North Carolina hometown and seeing all the white kids immediately climb out. The difference was that in Atlanta, it seemed everybody, black and white, was fleeing from him.

In public Campbell quarreled even more with reporters, belittled critics, and clashed with Olympic organizers. It clearly got his goat that the city’s business leadership ignored the positive changes in parts of city government; he was thrown under the bus for Olympic shortcomings, many of which had more to do with the shoestring budget of the privately funded Games than they did with City Hall.

Campbell became increasingly absent in his second term. The top-caliber people drifted away. The administration that followed was better at sycophancy than governing. The mayor, when he surfaced, just seemed mad—as he had some reason to be. He was clearly no longer “the one.”

You could feel his grip—and that bright possible future—slipping. Details wouldn’t come out until years later, during his trial on corruption and tax evasion charges. Most people have forgotten that Campbell was acquitted of all four corruption charges against him. The three guilty verdicts stemmed from tax evasion, in which he failed to report roughly $150,000 in income; he was sentenced to 30 months in prison. But criminal or not, the testimony painted a troubling picture: alleged payments from city contractors via his poker buddies, questionable campaign contributions, an affair with a beautiful young WSB News broadcaster who was showered with money and plane tickets of dubious origin.

Campbell, who has been back in Atlanta regularly but mostly out of public view the past few years, and I are still friendly when we cross paths. He chooses not to discuss any of this—and declined again when I emailed him not long ago.

I can’t see inside anyone’s head or heart. But it seems to me that the self-protective detachment Barack Obama gets criticized for by Republicans, and his steady refusal to “be more black” that quietly irritates so many African Americans—these are the sort of emotional devices Bill Campbell could never master. He got stuck, writhing in the middle. It’s a shame. We had a Barack there for a bit.

Douglas A. Blackmon is the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. He was the longtime Atlanta bureau chief and senior national correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and now hosts American Forum, a weekly public affairs program produced at the University of Virginia for PBS stations.

This article originally appeared in our March 2015 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)