On a warm Friday at midnight, Pharr Road and East Paces Ferry remain in perpetual motion. Uphill, downhill, around and around, a stream of pedestrians swarms against a backdrop of neon and headlights and music. Blond women with suntanned shoulders and tall men in crisp shirts and signet rings duck into the dark niches of Otto’s and Peachtree Café. Swaggering packs of college boys in Bermuda shorts gravitate to the shoulder-to-shoulder chaos of East Village Grille or Acme Bar and Grill. From the street, Buckhead ‘s second-story patio bars look like over booked cruise ships ready to chug off into the night.

On a warm Friday at midnight, Pharr Road and East Paces Ferry remain in perpetual motion. Uphill, downhill, around and around, a stream of pedestrians swarms against a backdrop of neon and headlights and music. Blond women with suntanned shoulders and tall men in crisp shirts and signet rings duck into the dark niches of Otto’s and Peachtree Café. Swaggering packs of college boys in Bermuda shorts gravitate to the shoulder-to-shoulder chaos of East Village Grille or Acme Bar and Grill. From the street, Buckhead ‘s second-story patio bars look like over booked cruise ships ready to chug off into the night.

New arrivals cruise slowly, pausing in front of Club D or Candide to see who is waiting in line. And, of course, to be seen. Carloads of exuberant men roll down their windows and call to women on the sidewalk, “Hey, where’s a good place to go tonight. So where are you going? By yourself or meeting a guy?”

As best I can surmise, a good place to go tonight is The Avenue, a discotheque next to C.J ‘s Landing, a beer-patio- and-guy-with-a-guitar bar. The line wraps around the front of the building to the end of the block, as thick as the sidewalk can hold. Even by warm Friday night standards, The Avenue is crawling.

A large American car pulls up and deposits four almost identically clad, almost-clad females onto the curb. They all wear tight black mini dresses though not all four should—and they teeter on high heels to the front of the line. The prettiest, wearing a black bolero hat, steps up to the tall man who is standing at the entrance to the club. He is the St. Peter of The Avenue.

“You watch. They’ re going to get in, ” remarks a bystander attired in blue jeans and shirt-sleeves. This he directs to a group of about 15 other people who are loitering in the street in front of The Avenue.

“She is nice,” says a guy next to him. The young men put their heads together for an admiring dissection. Before they get their fill, the nice one and her friends are in the door. No one protests. The guys in the street look at each other and laugh.

“So what’s going on here?” I ask the first guy. “What ‘s all the commotion about?”

“These people are all in line to get into The Avenue. It’s new. The guy at the door is choosing who gets to go in.”

“But who are these other people just standing around?”

“These are all the people watching the people who are trying to get in to The Avenue.”

And this is Buckhead on a warm Friday at midnight: wannabes watching wannabes. The scene validates everything I have ever believed about going out in Buckhead. Having fun might be the occasional byproduct of the experience, but it is not the purpose. Not fun in the carefree, unselfconscious definition of the word. Buckhead fun is more like that in a high-stakes game of chess, where the moves you make are calculated to one effect: winning. In the night air is the palpable sensation of trying.

Virginia-Highland has its strivers, but no place will turn you away for wearing blue jeans. After dark its woody pubs are the convivial land of a thousand light beer commercials. Little Five Points, with its anti-fashion activists, surely tries to make its own kind of statement. But in those two hubs, sincerity is, if nothing else, stylish. In Buckhead, sincerity is a moot point. You dress, you’re up for it, you go forth and conquer.

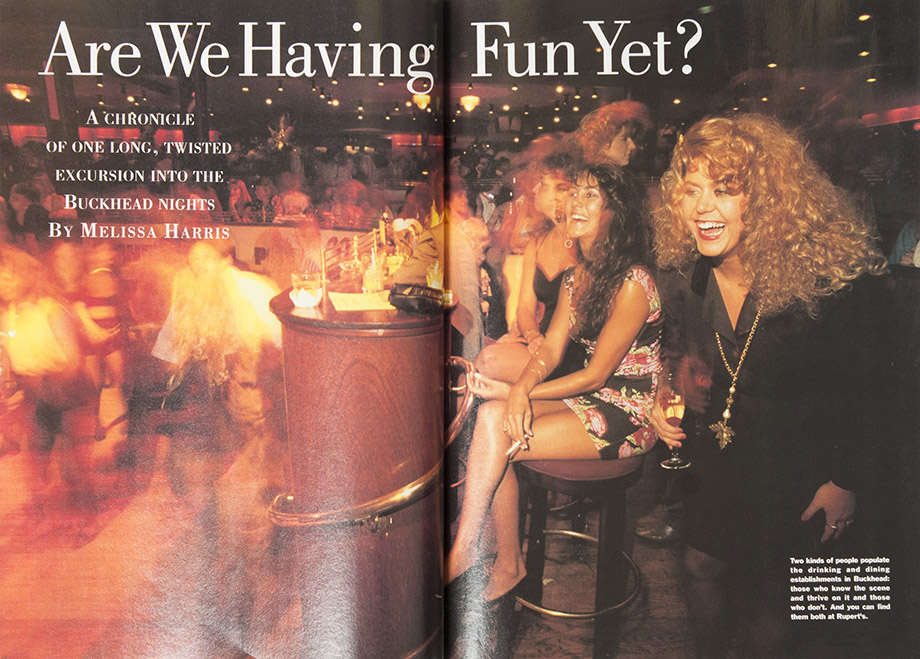

Two kinds of people populate the drinking and dancing establishments in after-dark Buckhead: those who know the scene and thrive on it, and those who don’ t. The insiders and the outsiders. Given the choice, I will usually go elsewhere. Given no choice—when an obligation or majority vote determines my agenda—I worry about what to wear and what to say and where to park my car in Buckhead. Upon arrival, I watch the insiders and wonder if everyone else really feels like an outsider, too.

But I know people who prefer Buckhead, who are fed by it, who are baffled by skeptics like me. I decide to enlist them to show me the Buckhead the “tourists” don’t see. Anyone knows some places where you can go for an evening in Buckhead, but these are the people who know where you go.

The first person who comes to mind is Michelle. A salon industry consultant, she is 29, self-assured, ambitious and recognizes lots of people in the clubs. We met last winter through a friend at Azio, the new Italian restaurant-bar-haunt in Buckhead, and took an instant though inexplicable liking to one another. Instant because we share some sensibilities, inexplicable because she doesn’t share my skepticism about Buckhead.

“You want me to show you Buckhead?” Michelle says maternally. “Come on. I’ll take you around.”

The other expert I line up is Bob, a stranger to me but a celebrated insider to the Buckhead scene. I learned about him from a local restaurant manager (“He knows all the ins and outs of Buckhead”) who gave me his phone number. When I call Bob and ask him to guide me through Buckhead nightlife, he has no questions and is immediately agreeable. He calls himself a nightlife “professional.”

“In Buckhead, you have what I call your rookies and your professionals,” says Bob on the phone. “Weekends are for the rookies. Tuesday and Thursday nights are for the professionals.” We agree to meet Thursday at Beesley’s of Buckhead, a restaurant and wine bar. A professional hangout on a professional night.

Bob’s name isn’t really Bob. But by Thursday he will have decided that his real name can’t be used. He has this life and then he has his life with his kids, and the kids come first. By then, my Buckhead insecurities will have proven well founded. I really don’t know what to wear or what to say. I don’t even know the most rudimentary tricks of parking in Buckhead. By Thursday I will learn what I have always suspected, that in Buckhead you have your rookies and you have your professionals, and I am a rookie.

But the week is still young.

Tuesday night at Rupert’s. Oh yes, it’s Ladies’ Night. The crowd is late 20s and up and, on the whole, not sophisticated. “White pumps and suntan pantyhose!” moans Michelle, who takes grimacing notice of every female so outfitted. She grimaces a lot that night.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s—the last shudders of disco—Rupert’s was one of the most famous nightspots in the Southeast. Then it was called the Limelight, and Southerners from all over came to gape at the strangely dressed people pulsating on the dance floor. Preppy college girls and secretaries dressed in fishnet stockings and gold lipstick came to be uninhibited for an evening. Live sharks and, at another time, tigers actually circled under a translucent dance floor. The private rooms with sofas and glass-topped coffee tables developed their own sordid reputation.

Rupert’s, heir to the Limelight facility, is about as aesthetically unfascinating as a disco could be: crimson carpets, dark wood, a hardwood dance floor and stage. It attracts a lot of women in white pumps and suntan pantyhose, not-yet middle management types, and out-of-town software salesmen. Most of the men wear suits, or jackets and ties, and stand around with a drink in had, staring at the dance floor. The music is Top 40, delivered by an 18-piece orchestra with a constantly rotating lineup of singers.

One of the first men we talk to at Ladies’ Night is David. Michelle knows him from Club D, where he works. “But I have a day job, too,” he quickly adds. He tells this to all the workingwomen. David looks to be in his early 20s, with a dark, flattop haircut and the energy and attention span of a hummingbird. He seems bored by attempts at normal conversation, and he never answers a straight question with a straight answer. “People tell me I look like Richard Gere,” he says, leaning close to a woman he has just met. “Do you think I do?” Before she can respond, he has turned and slipped his arm around the waist of another nearby female.

I run into David every night that week. “He’s a boy toy,” Michelle says later.

Michelle has a serious boyfriend in another state, but she has male friends in Atlanta she calls boy toys. Among boy toys, she explains, are babycakes (men in their early 20s), honeybuns (men in their mid-20s to 30s) and sugar daddies (men in their 40s and up).

The crowd at Rupert’s is mostly white. There are several black men, nearly all of whom are dancing with white women. Aside from Michelle, a tall, striking Jamaican, there are few black women in the club. She is pulled aside by a 6’6” black man in a red tie and dark, pinstriped suit. Calvin also works at Club D and is someone she knows. Calvin tells her he wants to dance with me.

On the dance floor, Calvin stares impassively over my head at nothing in particular and kind of marches in place for the first minute or so. After brief opening remarks, he begins to interrogate me aggressively about my marital and dating status. “If you’ve got a boyfriend, what are you doing here?” he challenges. When I try to put him off in a friendly way, he just laughs. He thinks I am baiting him. After several songs I’m ready to sit down. But each new song just so happens to be one of Calvin’s favorites. Calvin hovers for the rest of the night and, like David, will materialize out of the ethers every night I am out.

“You’re just the kind of girl I like,” says Calvin.

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“Not too skinny.”

I laugh and say thanks a lot. He sincerely means this as a compliment, but the comment irritates me for the rest of the evening. I go to the restroom and talk to Helen, the attendant and only woman in Rupert’s besides me who is wearing sensible shoes. She explains that she has a metal plate in her leg and can’t stand for long periods of time.

I smoke two of her cigarettes while other women, very skinny women, use her hairspray and lipstick and breath spray, leaving $1 bills in her basket. I try to engage Helen in a conversation about the women she sees in the bathroom at Rupert’s on Ladies’ Night, but she has worked here too long to remember any particular stories that seem worth telling.

Everyone seems sober and well behaved, I think, remembering a recent evening at Aunt Charley’s where I saw two girls in the bathroom stall. Under the door I could see one of them sprawled on the concrete floor in front of the toilet. Later, when the two girls emerged, I could tell by her aroma and ashen face which one was not having a good time.

“I bet this isn’t the kind of place where women come into the bathroom and get sick,” I venture.

Helen rolls her eyes at me to indicate I must be kidding. I don’t really want to go back out. I keep hanging around, just standing in the restroom and talking to this grandmotherly woman in flat shoes. I laugh and tell Helen what Calvin has said to me, fishing for reassurance.

She doesn’t get it. “Well, he’s right,” she looks me up and down admiringly. “You are a nice size.”

Two women fussing over how good the other looks and teasing their hair overhear our exchange. “What is he talking about?” one of them says indignantly. “You look great. Men are PIGS.”

Back at the bar, I ask the bartender what I can safely drink after Jagermeister, a hideously sweet yet popular liqueur Michelle has selected for us. He shakes his head and laughs. “You gave up your right not to be sick when you started drinking Jagermeister.”

“Standing alone by the cash register and chain-smoking is Frank, a brooding 30ish Italian with a thick accent who is either weird or drunk or both. At first he tells me he is a civil engineer, but later says he runs a restaurant-bar downtown. “I have a lot of female friends, and I don’t sleep with them,” comments Frank, impervious, as far as I can tell, to whatever it is we are discussing. “Look at me. I keep the coupons.” Frank opens his billfold and shows me a 50-cents-off coupon for condoms. He looks at me for a reaction, but I’m not sure what kind.

Frank offers me a drink. “My drink is free here,” he notes.

“Why?” I ask.

He smiles and shrugs. “I don’t know.”

I begin writing down his comments on a napkin on the bar. He doesn’t seem to notice. The next day when I read the napkin it says, “I try to make communication with someone who has loneliness, and I’ll just make a call to you so say hello… I walk into the trees and I walk into the woods and I feel loneliness and that’s the way I love it… It’s very complicated, my life, and I love every minute of it.”

Michelle appears at the bar. She can’t locate her new boy toy, a 23-year-old stockbroker who just moved into town from Vermont, and she has to work in the morning. No sooner have I pulled out my car keys than Calvin darts up and wrestles them from my hand. “I want to see what kind of car you drive,” he says. He insists that he is going to walk me to my car and kiss me goodnight. Michelle intervenes and retrieves my keys. Frank stops me on my way out the door and says again that he wants to buy me a drink.

It’s almost 3 a.m. and we want food. Michelle and I drive a few miles south on Peachtree to the inevitable source: R. Thomas, a hip 24-hour restaurant with $7 hamburgers on nine-grain bread that take an hour to arrive.

“Did you have fun tonight?” Michelle asks incredulously. “I mean, I had so much fun. That was fun! Do you normally have this much fun?”

Yeah, sure, I thought it was pretty okay. I mean it was fun, I guess. It surprises and pleases me that Michelle thinks it was extraordinarily fun. Maybe I’m more clued in than I give myself credit for.

Tomorrow, she is supposed to call the cute boy from Vermont. She has his phone number. “If he thinks I’m not going to call him,” she chuckles, “he’s in for a big surprise!”

As we are waiting for our food, the boy toy from Vermont walks into R. Thomas. He is with another woman from the nightclub.

All week long I have exposed my knees in Buckhead. On Thursday I put on a straight black skirt that hits me midcalf, with low heels and a long jacket. I am going to meet Bob and the professionals, the grown-ups, and I don’t want to handicap myself.

The sun is still out when I walk into the bar at Beesley’s. There are about 10 or 12 people there. A handsome 30ish man in a nice suit blocks my path at the door and says, “Hel-lo! Are you married? Engaged? Living with someone? Got a boyfriend? Pinned? Lavaliered?” He takes it for granted that any woman who comes into Beesley’s is familiar with the college fraternity ritual of getting “pinned” or “lavaliered.” I am in a world where successful adults still speak fondly and often of their Greek affiliations.

I assume he is Bob, who is expecting someone who fits my description, but he isn’t. His first name is King. King leads me to a booth where Bob is entrenched with two other men. I am not surprised to see him because I had no expectations, no idea what a nightlife professional would look like.

Bob is short, heavyset and bald on top with a silver beard and searing black eyes. He is wearing a casual dark brown shirt with a print pattern and cotton slacks. Next to him is Jerry, a big man dressed in a suit with a pocket-handkerchief. Jerry’s hair is sprayed and he wears a gold ring with his initials in block letters. I slide in next to Peter, a low-key Australian in a tan suit, who is drinking wine.

Bob reacts to me the same way 1 react to him: not at all. He introduces me to Jerry and Peter but still asks few questions. “You’re late. Order a drink. I’m four ahead of you,” he commands. “I always drink five in a row and then pace myself.”

He and Jerry launch into a running dialogue that consists almost entirely of rib-nudging and private jokes. No one feels comfortable. Jerry tells jokes about blacks, women, Jewish women, homosexuals and lesbians. He discriminates against no one. Bob laughs and laughs and gnaws on the straw from his drink. Every time I get halfway through my gin-and- tonic, he orders me another one.

Amy, the advertising manager of Beesley’s, comes over to the table to banter with the men. By now it is dark, and the discussion turns to Buckhead nightlife.

“I saw a guy in here the other night wearing a shirt that said I’LL SLEEP WHEN I DIE,” says Bob. “Isn’t that great? Have you seen the one that says EXCESS IS NOT ENOUGH?”

Amy tells them about good put-downs she’s heard women use on men in Beesley’s. Jerry turns to me, “Melissa, what do you say to men in bars who won’t leave you alone?”

I think about Calvin. “Um, well, I don’t know. I guess I’m just too nice to people. I really don’t know what I say.”

Everyone just stares at me. Bob orders me another cocktail.

I am already asking for club soda when Bob and I make the second stop on our tour of Buckhead. Otto’s, just across East Paces Ferry, is even darker than Beesley’s. The crowd is a little older, more sophisticated and mostly male. The women I see are with men. There is a piano man in the middle of the room. I don’t imagine anyone is ordering beer. Bob gets me my club soda and a gin and tonic.

“People come here to pound ’em,” Bob announces. “Not to dance, not to eat, not to pick up women. This is a drinking bar.”

Bob knows the bartender and most of the customers. Peter is there, with his wife, a slim brunette in a blue silk outfit, who doesn’t say much. I sit next to them at the bar while Bob bounces from person to person. He brings a few older men in suits over to meet me. They don’t know why they are being introduced to me, and I can’t think of anything interesting to say to them. I feel like a nun at a bar mitzvah.

Once, after witnessing my conversation with one of his friends, Bob barks at me in an annoyed tone, “Don’t say, ‘Really.'”

Whatever natural wit and conversational skills I possess have abandoned me, and I say “really?” in response to almost everything his friends tell me.

“Why not?” I ask Bob.

“You sound naive.”

(I don’t know what to say!)

The evening is progressing strangely. I tell Peter and his wife what Rob said to me about saying “really.”

“What will you say?” Peter says to me. He sounds like he is slurring his words, but it may just be his accent. Peter waves his arm toward the bar. “You must take things from these people and rise above them.”

Peter points to a doughy, boyish man in a pullover shirt standing at the bar. “That guy smoking a cigar, heesh gotta trust. So he smokes his cigars and checks on his interest once in a while.”

Bob and I don’t stay at Otto’s long. We have had just enough alcohol to feel uneasy about our mutant pairing but not enough to laugh about it. Otto’s is a professional bar where he mingles with other professionals. Everyone can see that the young woman with him tonight is not a professional, not someone they recognize—literally or figuratively—and Bob must know they see this and are thinking things.

But the next stop is Club D, and there will be plenty of amateurs. Plenty of camouflage for me.

Club D calls itself a piano bar and dance club, but even the piano bar in the front of the club has a throbbing, disco atmosphere. People would like to watch people here, but there are too many of them packed too tightly together. Bob knows a few people but not most of them—and vice versa. Tonight is Ladies’ Night at Club D.

Once we are inside Club D, Bob becomes friendlier, more relaxed. We sit in the piano bar overlooking Peachtree Street, and Bob illuminates me—at my request—on the subject of Buckhead women. His theory is that 45 percent of the women who come to Buckhead come to dance, have a few drinks and a few laughs and go home. Another 35 percent are seeking some sort of male reinforcement to feel better about themselves but not necessarily for a partner. The other 20 percent, he says, are looking for a mate. I do not question his numbers, but I wonder how he came up with them and why.

Bob introduces me to Denise, one of the owners and the “D” in Club D, formerly Oliver’s. She explains that Club D is the same concept as Oliver’s but with a different attitude. Denise is a fine-boned blonde in leopard-print pants and a blouse with a leopard-print lapel. We discover we are both from Birmingham. This amuses me in a smug sort of way. I imagine the people who would say Club D is the hottest bar in Atlanta would be the first to make a wisecrack about Birmingham.

Meanwhile, Bob is maneuvering through the crowd, but he sends a procession of acquaintances over to the bar where I am seated.

One of them is Michael, a taciturn, sharp dresser who is in management at The Ritz-Carlton. The entire time I am talking to Michael he keeps one eye on me and one eye on the rest of the room. There is Holly, a slightly daffy model I once met at Rupert’s with Michelle. She tells me she got so excited over a song she heard on MTV the other day that she hurt herself dancing around her living room.

Throughout the evening Bob makes observations about women, and about himself and women. “Women trust me because I’m nonthreatening,” he says. “I’m a father figure.” Later he tells me that, on the way back from the bathroom, two different women approached him and asked him if he were alone. “See what I mean?” he says. The father figure describes young women in skimpy outfits as “hard bellies and bullet tits.”

This is how you pick up women in Buckhead, says Bob. He wets a $20 bill and pastes it to his forehead. He says this derisively, but in a little while he shows me his Rolex and remarks, “That’s $20,000 you’re looking at.”

“Why would you want to spend $20,000 for a watch?” I ask him, genuinely curious.

“Because I can,” he snaps.

Bob is one of those who knows—or talks like he knows—just enough about women to be dangerous. He would make John Derek feel proud, and he is firmly in command. He spends much of the rest of our time at Club D analyzing me, how I should dress, how men react to me. “Here, drink this.” “Don’ t write that down. I’ll remember everything and tell you later.” “You dress like a damn schoolmarm. You should show off those legs.”

At Club D we hook up with Joni. Her real name is not Joni either. She is very friendly—very friendly—and very outgoing. Later in the evening I form a theory that may explain why she is so friendly, and I decide not to use her real name. Joni is 29 and looks 23. She comes from a wealthy family and her mother was a centerfold. She says she goes out at night because she spends all day long talking to bankers, stockbrokers, doctors and lawyers. Joni is a hairdresser.

Bob, Joni and I talk at a table in the back of Club D for a long time. They already know each other, and each of them gets up periodically to talk with other people they know. We vote to go down the street to Candide.

As we are leaving, Bob admits that earlier at Beesley’s he was indeed dreading this night. Now he says he is having a good time, a fact that seems to astonish him. “You come across as very naive, but you didn’t just fall off the turnip truck,” he laughs. “You should really use that to your advantage.”

I am glad to finally have Bob in my corner. I think.

Everyone says Candide is a European bar. The main lounge in the back is a long, low-slung room furnished with a bar, sofas and an aquarium, and it has white brick walls washed by ice-clue lights. It’s the kind of place where people lounge around on the sofas and try to look worldly and nonchalant, but mostly they just look at each other. One Saturday night I was in Candide with a Dutch friend, and I asked him if this was indeed a European bar.

He frowned. “These are sill people in here.”

Fronting Peachtree Street is Candide’s art gallery as well as a cave like disco room with blazing fluorescent murals on the wall. The music is mainly European club mixes, with some smarmy ’70s disco music thrown in for irony. Dancing with a partner, especially one of the opposite sex, brands you as passé.

Candide hosts all sorts of special evens, such as champagne parties and art openings. Near the front door—where they extort a $7 per-person cover charge Friday and Saturday—is a sign for “House Vogue,” left over from an event Candide has canceled. I ask a tall black man wearing eyeliner if House Vogue is the night where people come here to “vogue.” Vogueing, the subject of a hit song by Madonna, is a dance craze in which you pause periodically and strike a pose like a fashion model. He doesn’t hesitate. “Oh, no. Vogeuing is out. It’s dead. It’s been out for two years.” He looks at the other door person and smirks. Whatever is hot with mainstream America will only date you at Candide.

Candide is almost empty when we arrive, and even more so when we leave. I spend most of the time at the bar talking with Joni and a young white guy with dreadlocks who tells me his close friends just call him “Mudhead.” He, too, is very friendly, and he sits at the bar and smiles. Every time I look at him, he smiles.

Prudishness has no place at Candide. I discern this when I am standing at the bathroom mirror applying lipstick and a young Hispanic-looking man with a pompadour and a baggy suit walks into one of the dark stalls and urinates. When he comes out, he is friendly and enthusiastic and says his name is Fab. He gives me three phone numbers and writes, “Call me!” in my notebook.

Joni talks to the bartender. She says he saved her life one night, but she means he cheered her up. “People say this is the snottiest bar, but I love it,” she says to him. She orders a shot of goldwasser, a magical-looking liqueur with metallic gold flakes swirling around in it. I order one too, but Bob sees and takes it away from me. He knows what you should and shouldn’t drink at 2:30 in the morning.

Joni and I go to dance in the disco room, just us and about five Asian people. Bob looks in periodically, and decides that when I dance I am really uninhibited and he sees another whole side to me. I realize I am long overdue for a club soda.

The evening has reached that decrepit stage when you can no longer ignore the feeling that you probably should be at home, in bed, alone, with the covers pulled over your head. So we make the only rational choice: We go to The Gold Club.

Our party has grown to four. In the backseat is Joni and a friend of Bob’s, a 40ish man in a summer suit with a Southern accent. Bob and I, Bob’s car phone and answering machine are in front. Bob can’t believe I have agreed to go to The Gold Club. He thinks this is great.

Joni produces a small wad of aluminum foil. Inside is a green, hallucinogenic mushroom. She eats a piece and offers some to the rest of us. Bob’s friend says he has never tried mushrooms, but he takes some anyway. Bob and I decline.

When we arrive at The Gold Club, Joni tells the bouncer she works at Cheetah III and she goes in without paying. “You do?” I say to her, surprised less by the fact that she is an exotic dancer than by the fact that I am the last to know. She furrows her brow and puts her finger to her lips to say, “Shut up.” She is only lying.

On the way to our table, she pulls me aside and says to keep an eye on Bob’s friend because in about 45 minutes that mushroom is going to kick in. He keeps saying, “I don’t feel anything.”

The Gold Club is so desolate you could almost hear a G-string drop. There are more naked women dancing than there are men sitting and looking. One of the dancers is Bob’s neighbor and she stands at our table chatting brightly, stark naked. Two other dancers come over and Joni and I talk to them, too. Secured in their garters are jumbled patties of paper money, three inches thick. At our table the women outnumber the men 2-to-1, and even though three are nude, our eyes belie a sense of conspiratorial sisterhood of a shared and heady secret. It is funny and preposterous that men will empty their billfolds for this, and we all know it.

Bob is watching me for a reaction, any reaction. I have never been to The Gold Club before. To me it is like Disney World, only the characters wear different costumes. I am not shocked. In fact I feel more comfortable at The Gold Club than anywhere we have been tonight. It’s straightforward. Everything is just what it seems. There are naked women dancing for money, and there are men paying women to dance naked.

We hang around until the last dance, about 30 more minutes. When the valet brings Bob’s car around, the sense of foreboding returns. As we pull out of the parking lot, Bob’s friend asks Joni for “a bump,” but I do not look into the backseat to see if there is any cocaine. I don’t want to know.

We drop the two of them off next door to Rupert’s at Club 112, which opens at midnight and closes at 6:30 a.m. The two of them pass by the big, furtive bouncers in neckties and pass through the opaque blackness of the open door. From the front seat of the car I decide I have seen enough.

But there is one problem. I don’t know how to park in Buckhead.

At 7 p.m., more than eight hours ago, I valet parked my car in a parking deck near Beesley’s. At 2 a.m. the valet service closed, and my keys were locked up for the night. I cannot get into my car. Tomorrow I will realize this is a blessing, but not tonight. Bob agrees to drive me home. On the way there I realize I also cannot get into my apartment. “This is getting more interesting all the time,” Bob says.

Then I remember the window with the broken lock, the one I have feebly jammed with a stick because the rental office has yet to come over and fix it. For the first time, I hope that the stick won’t hold. I have never tested it.

We rattle the window and shake it, but the stick holds firm. I try to push the panic back down into my stomach and my mind runs through a list of friends who might not be too alarmed if I rang their bell at 4 a.m. and asked to spend the night. I can’t think of anyone.

Bob thinks he can remove one side of the window. He pulls and grunts and maneuvers, but it will only come part of the way out of the frame.

Then, suddenly, the window shatters into tiny pieces, leaving a hole large enough to climb through. Relief floods over me. I am an outsider on the inside once more.

This article originally appeared in our October 1990 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)